It starts on August seventh, the day I have a black eye because you threw my phone backwards over your head and my eye was right there. I couldn’t speak for an hour, the pain was so sharp. I held a pack of peas over my eye, entertaining you with your toys in the dining-room-turned playroom (everything is yours now) while I wept internally. The next day I put you in the backpack, and we hiked up Sugarloaf Mountain, my eye throbbing. Halfway up, I stopped short. I’d never seen a coral mushroom before, never expected its vibrant purple brain-coils here. This beauty had been transported from a coral reef to our Michigan hill.

Look! I said. Isaac, Look at that mushroom!

We saw three more clusters, and you repeated mush-room, mush-room, pointing too. That was it: you were mesmerized. This would be our summer.

You see them all before I do. The first couple of weeks, I tell you, No touching, Poison, and you repeat this with a somber face, and bend over with your hands flown behind your back to get a good look at the stems. The third week, we find puffballs, and I show you the glory of stomping them and watching their smoke poof up in fine particles, greenish-brown clouds that swiftly drift away like fairy dust. You cheer as you lower your foot. You begin stomping not just puffballs but all the mushrooms. But I don’t want you to be a destroyer of the forest. I want you to be a gentle boy.

Let them live. I turn your shoulders down the path. Let’s find more.

The mushrooms will thrive even if they’re squished; you’re only spreading spores. You are two. Squishing is a delight.

Each day at naptime and bedtime, we read the full-color mushroom identification tome a friend bought for you. This is the book you choose every time I ask you to pick a story. You sit on my lap in the rocking chair, enraptured, as I turn the pages and read aloud the names, one by one. As the days and weeks pass, I learn them: Black trumpet, purple coral, yellow coral, agaric, russele, hedgehog varieties with orange teeth instead of gills, boletes, amanitas, chicken of the woods.

We begin to slip on the no touching rule. You touch one, then another, unable to resist. I try to stop you from picking the mushrooms, but you are quick, and once you touch one, you grab another. Finally, I surrender and let you pick all but the red ones, which surely must be poisonous.

When I was younger, I collected rocks and shells from beaches, pine cones from forests but over the years, it began to feel wrong. These are not mine to take. I’m disrupting this place by claiming a piece of it. At Echo Lake, I gather mushrooms in a cloth bag to make spore prints as gifts for friends. I’m breaking my rule, but I tell myself it will be a good lesson for you to see the marks spores make.

At home, I set my finds on white paper, and research them, trying to identify what I’ve gathered. I read that there are not one or two poisonous varieties of mushrooms, as I’d imagined, but dozens. Dozens. Most poisonous is the Death Cap, one of the Amanitas. White. It looks benign, like the mushrooms I see in the grocery store, except for the slight green hue to its cap. A rice kernel-sized bite can kill an adult. They flourish in pine tree habitats, like this one.

I scan back through my pictures and see you holding a white mushroom. A Death Cap? I zoom in. No, it has a purple hue, not green–perhaps a wood blewit, not poisonous. My heart races. How stupid I’ve been. You could have died. You have had your hands on everything and then in your mouth, teething. I throw away all the mushrooms I’ve brought home, wipe down the counters, wash my hands. New rule: We only touch mushrooms with a stick.

Maybe someday I’ll tell you the whole story of this time. How when it all started, I made sure my life insurance was in place and asked the lawyer if I could make last-minute changes to my will. Sure, she said. I’ll even do it free of charge. I laughed, imagining her billing me after I’m dead.

I worry that because I’m your only parent, if I get a bad case of it, who will take care of you while I recover? Or if I don’t? The friends I’d written into my will haven’t touched you in six months. They have instructed their children not to touch you. They perceive you as a source of contagion, believing you’re more likely to spread the virus than other people around them because you are a toddler who touches everything. In July, at the big lake, you run up to play with their son, as you always have. You stand, bewildered and motionless, when he runs down the beach screaming, Get away! Get away!

You had just gotten used to the daycare I’d waited for a year to get you into. You cried those first weeks and clung to me, and I had to peel your fingers off from my body and leave you wailing in a stranger’s arms, a forced smile on my face, assuring you it would be okay. I’d get into the car and weep.

Then, one day, we walked into the classroom and they were playing with a parachute, all the tiny people running under it as your two favorite teachers called, Woo! Go! Run under! You wiggled out of my arms and strutted over to the group. Looked up and laughed. Didn’t even notice when I waved and called goodbye, and tried to catch your eye before walking out the door.

Then I had to remove you from all those new friends in hopes of keeping you safe. We both stayed home and spent all of our time together, mornings and afternoons and evenings, while I scrambled to teach online with you in my lap.

We tried to start daycare again in July, but every week you got sick, and we quarantined together, again, at home. A week on, a week off, at home with the stress of getting tested and waiting, and with your fury, wanting to be out in the peopled-world again. We went to the woods twice a day during those quarantine weeks, before and after your naps, further and further out, down miles-long dirt roads so we wouldn’t run into anyone. I brought piles of snacks that you nibbled and then chucked across the back seat. You were teething and waking three times a night with those two-year molars that no one warned me would be so bad. I’d drive, exhausted, and walk, exhausted, and finally, something would catch me and hold my attention.

In late September, a friend takes us to the forest to hunt for mushrooms.

She’s in her eighties, hikes every day with a basket and a knife in hand. Tells me to bring my own. Teaches me which mushrooms we can eat, which ones to avoid. This one has been eaten by a slug, she says, pointing out the gap in its underside sponge. This one is too old, she says, pointing to its browning stem. Someone has gone before us on this trail, just after the rains, and toppled over the mushrooms that aren’t for eating, yanked out the good ones, leaving fresh dark divots in the earth.

We walk to Wetmore Pond, sit on the rocks, and look out. You stand up and run off in search of more. I forgot, she says, how they never sit still.

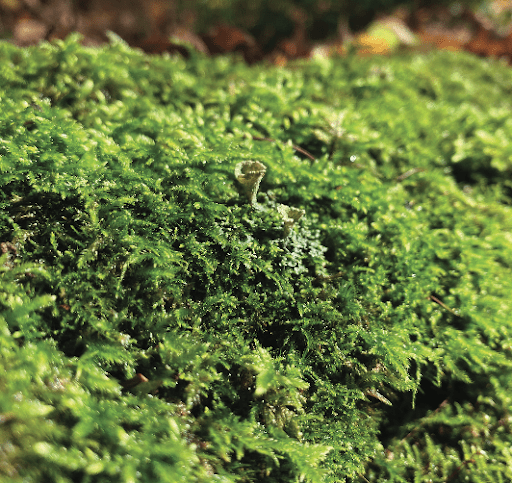

The longer I look at them with you, the more my attention is turned towards them, the more I find. I become as preoccupied as you are. I find them on the campus lawn while waiting, masked, for my students to finish their outdoor writing exercise. Out in the woods, there’s magic in staring down at a ten-inch-square piece of the earth, seeing nothing but leaves, and then, like a trompe l’oeil, my eye refocuses: Ah! There! This is a world I’d never noticed before. Not just the mushrooms but the moss and the leaves and the tiny evergreens that a scientist friend tells me were mammoths in the prehistoric age.

Crouch down and stare for twenty minutes at one small patch, its own rich microcosm.

Everything shifts. Imagine what else you’re missing because you haven’t known to look. A poet who is also a mystic says she sinks deep down into the earth, gets right into it, and asks what the moss is trying to tell her. I think about this. What are you trying to tell me, mushrooms?

Please notice the wood grain of the tree, the moss and lichen on the bark, the gills and the stipes, the pine needles and the leaves and the lake in the distance. Please notice the way the water glistens on the fresh mushrooms just after the rain, while others are older and dry. Please see this glorious arch of a stem emerging from a tree trunk, and the way my son’s fingers grace upwards as he stares down, his perfect tendriled curls, his sweet enchantment with each one he sees.

The Shameless stinkhorn, in the Phallacae family, makes me laugh when I spot it in the grass. It’s on its own, and I see it only once all summer. How did this single stinkhorn arrive here? Where did these spores come from? Why didn’t more grow?

I see the imprint a slug made on the underside of a mushroom, its sponge a puzzle with a body cut out.

We spot an Earth Tongue, which emerges from the forest floor in a stubby brown stem with a knob on top like the dirt slipping up to taste the air with its mouth. Imagine the soil beneath the surface of the earth, conspiring to rise up.

The part we see is just the fruit; there’s a whole network of fungi underground, a system underneath the forest floor that sustains the trees, carries nutrients in white webs. We have a hint of all this when we scratch at the base of the mushroom or when we dig up wood chips at the playground. Filaments of connection from one seemingly isolated tree to the next.

You move all day, and I trail after you or entice you in the direction we need to go. When other children join us in the woods, they’re annoyed at our inch-by-inch pace.

Sometimes, I think you’re too slow. You walk, meticulously searching until you see a mushroom along the edge of the path, and rush towards it. You crouch down beside it, craning your head to observe the stem. You study the top, your face an elated grin, full of pride in your find. I am not perfect. I get impatient. I urge you to move faster, sometimes, to go, already. You’ll take a few steps forward and then turn back, needing one last look. You force me to stop with you. And that’s when the magic comes.

I am in awe of your ability to find each and every one. I am in awe of your joy at even the most ordinary of mushrooms; those average specimens, brown and humble, stout in the soil, make you as happy as the fancy bright corals.

Everyone is excited about mushrooms this year. A friend says it’s because they thrive amidst decay and death, making new life under the rot. I’d never noticed before this summer that the forest is half rot, half life. All the fallen trees, twisting slowly into the ground, all the mushrooms growing on the downed trees, and speckling the trunks with their Turkey Tails and Chicken of the Woods and Shelf Mushrooms. I used to think of the woods as a slowly changing place, turned by seasons, but it’s constantly in motion. If I could get closer, closer, maybe I could hear the leaves sprouting and disintegrating, the fungus spreading underground, and bark cells multiplying.

Out at Echo Lake, I notice all the birches that take root in the rotting stumps, making their homes from decay. How strong those curved roots are, how cunning to find purchase here, in what might look useless. I notice trees perched on cliffs, clinging with curled roots to the dirt, and impossibly arched trunks that reach out over rivers or other trees. My favorite is the pine tree that tilts further and further toward the lake each year but is somehow still alive.

Watch this, say the trees and mushrooms and ferns. There’s still so much living to do here.

Watch how we hang on.

The earth will provide reasons to survive. This color pink and purple, this new growth after the hard rains, this rotting log transforming into a rich bit of soil for all the mushrooms, then the birch trees, then the pines. That’s the order of replenishment. You can tell it’s a new forest if it’s full of birches.

The river with the rope bridge reflects yellow leaves now, not green. Soon, they will fall, and the water will catch them, and the light will leave us, as it does every September.

The pandemic hasn’t passed. Winter will be here in a month. Each year, we get about 200 inches of snow, from October until late April; we live in gray.

A sign at Thomas Rock Scenic Overlook says that Lake Superior produces the greatest lake-effect snowfall in the world. It is also the world’s largest body of freshwater by surface area. I’ve joked to my East Coast friends that they’ll want to be here when the apocalypse comes. We have all the water. Corporations have stolen it from the rivers that flow from the lake. And for centuries, colonists have been stealing it from the Anishinaabeg people, whose lands these are.

I don’t belong here, though I have come to see these woods as “ours,” as if I can claim them from the onslaught of tourists who wander deeper and deeper into them each year. I know that I, too, am an interloper; the whole system in which I live is based on theft. The house I own was built in the 1800s by settlers on Anishinaabe lands, and every day, unintentionally, I pollute and litter just by living on this earth; I use water and natural gas and car fuel. Somewhere in this year, in the chaos and sleep-deprivation represented by my messy kitchen, I stopped recycling everything I could, throwing away plastic containers when I thought I was too tired to rinse them. How much of my trash is sitting in landfills here in Michigan? And in Rhode Island and Montana and Massachusetts and New York and Nebraska. Narrangansett, Wampanoag, Massasoit, Blackfoot and Crow, Shinnecock, Montaukett, Pawnee?

Next year, will you still care about the mushrooms? Will you still ask to read the guidebook a friend got you, repeating all the names after me? You’re no longer a baby, no longer a toddler. I see you becoming a little boy.

I wish for you silently into the trees: Please carry this time with you as you grow. On your hard days, come to the trees and lean against them; let this place care for you. How lucky we are for these forests, how lucky for the mushrooms with their mysterious networks.

I rinse all the plastic and cans again, and put them out each Tuesday to be recycled. I pick up other people’s trash on the beach. I leave the dandelions in my lawn for the bees. As I have all my life, out in the woods or by the ocean, I look up and whisper, to whomever can hear me, thank you.

You keep demanding to see mushrooms, but I can’t find any. We go back up the trail where we saw the purple one in early August. I put you in the backpack so I can climb faster. I need endorphins more now that the light is fading.

It’s fall, buddy, I tell you. The mushrooms are going away for the winter. They stay in the earth, asleep, and come back out in summer. When it snows, they go away, like the bear in your book.

Like leaves, mushrooms change after they’ve fallen–browning, curling, glistening with seagreen mold. This one looks like ruffles of black satin furled against the earth. White corals turn black. Golden leaves buttress the decay. Everything on the forest floor goes wet and soggy, sinks, into itself and then into the soil.

One day, out at Craig Lake, we drive half an hour down a snowy dirt road. The air here is still, the lake quiet. The only people we saw here are half a mile back having a fire at the campground. I hike while you fuss in the pack. You’ve walked through the snow for half a mile, and that’s enough today.

All of a sudden, you shout, mushroom! I think you’re mistaken, that you’re just seeing snow. I stop. I eye the lumps and mounds around us, miles of white now covering the sticks and leaves and roots. And there. There they are–a cluster of twenty or so perched on a stump, topped in snow. You’re right, I say. I swing the pack down over my side and unclip your harness; I find you a mushroom stick so you can study them. We stand there for minutes. For hours. Days. Weeks. Crouched down, brushing the snow from mushroom tops, we talk about them together–their color, their gills, their stems. We stay here forever, webbed by a time both endless and too finite. We’re both hungry and cold. I’m eager to get to the warm car. I never want to leave.