My first glimpse into the horror and beauty that lurk uneasily in the human heart came in the late 1960s courtesy of the Biafran War. Biafra was the name assumed by the seceding southern section of Nigeria. The war was preceded—in some ways precipitated—by the massacre of southeastern (mostly Christian) Igbo living in the predominantly northern parts of Nigeria.

Thinking back, I am amazed that war’s terrifying images have since taken on a somewhat muted quality. It requires sustained effort to recall the dread, the pangs of hunger, the crackle of gunfire that once made my heart pound. It all now seems an unthreatening fog.

~~~

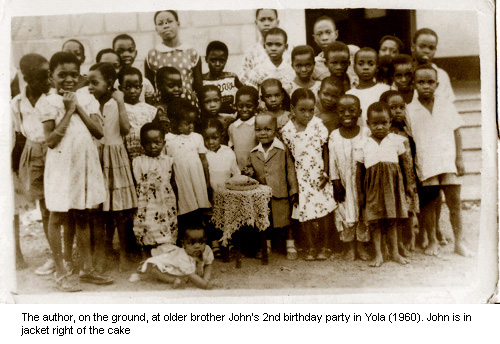

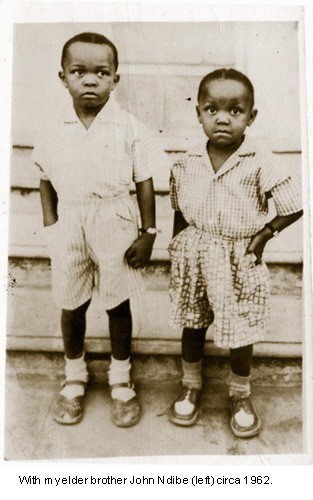

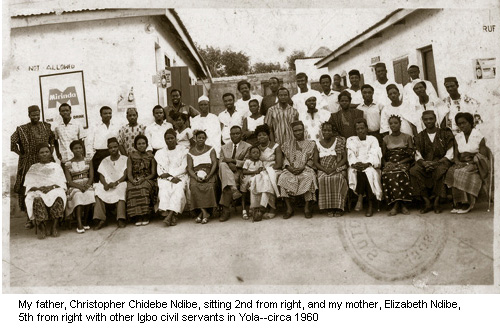

As Nigeria hurtled towards war, my parents faced a difficult decision: to flee, or stay put. We lived in Yola, a sleepy, dusty town whose streets teemed with Muslims in flowing white babariga gowns. My father was then a postal clerk; my mother a teacher. In the end, my father insisted that Mother take us, their four children, and escape to safety in Amawbia, my father’s natal town. Mother pleaded with him to come away as well, but he would not budge. He was a federal civil servant, and the federal government had ordered all its employees to remain at their posts.

The area’s Muslim leader arrived at the spot. Uninfected by the malignant thirst for blood, he vowed that no innocent person would be dealt death on his watch.

My mother didn’t cope well in Amawbia. In the absence of my father, she was a wispy and wilted figure. She despaired of ever seeing her husband alive again. Our relatives made gallant efforts to shield her, but news about the indiscriminate killings in the north still filtered to her. She lost her appetite. Day and night, she lay in bed in a kind of listless, paralyzing grief. She was given to bouts of impulsive, silent weeping.

Then one blazing afternoon, unheralded, my father materialized in Amawbia, stole back into our lives as if from the land of death itself.

“Eliza o! Eliza o!” a relative sang. “Get up! Your husband is back!”

At first, my mother feared that the returnee was some ghost come to mock her anguish. But, raising her head, she glimpsed a man who—for all the unaccustomed gauntness of his physique—was unquestionably the man she’d married. With a swiftness and energy that belied her enervation, she bolted up and dashed for him.

We would learn that my father’s decision to stay in Yola nearly cost him his life. He was at work when one day a mob arrived. Armed with cudgels, machetes and guns, they sang songs that curdled the blood. My father and his colleagues—many of them Igbo Christians—shut themselves inside the office. Huddled in a corner, they shook uncontrollably, reduced to frenzied prayers. One determined push and their assailants would have breached the barricades, poached and minced them, and made a bonfire of their bodies.

The Lamido of Adamawa, the area’s Muslim leader, arrived at the spot just in the nick. A man uninfected by the malignant thirst for blood, he vowed that no innocent person would be dealt death on his watch. He scolded the mob and shooed them away. Then he guided my father and his cowering colleagues into waiting vehicles and spirited them to the safety of his palace. In a couple of weeks, the wave of killings cooled off and the Lamido secured my father and the other quarry on the last ship to leave for the southeast.

~~~

Air raids became a terrifying staple of our lives. Nigerian military jets stole into our air space, then strafed with abandon. They flew low and at a furious speed. The ramp of their engines shook buildings and made the very earth quake.

“Cover! Everybody take cover!” the adults shouted and we’d scurry towards a huddle of banana trees or the nearest brush and lay face down.

Sometimes the jets dumped their deadly explosives on markets as surprised buyers and sellers dashed higgledy-piggledy. Sometimes the bombs detonated in houses. Sometimes it was cars trapped in traffic that were sprayed. In the aftermath, the cars became mangled metal, singed beyond recognition, the people in them charred to a horrid blackness. From our hiding spots, frozen with fright, we watched as the bombs tumbled from the sky, hideous metallic eggs shat by mammoth mindless birds.

The jets tipped in the direction of our home and released a load. The awful boom of explosives deafened us. My stomach heaved; I was certain that our home had been hit.

One day, my siblings and I were out fetching firewood when an air strike began. We threw down our bundles of wood and cowered on the ground, gaping up. The jets tipped in the direction of our home and released a load. The awful boom of explosives deafened us. My stomach heaved; I was certain that our home had been hit. I pictured my parents in the rumble of smashed concrete and steel. We lay still until the staccato gunfire of Biafran soldiers startled the air, a futile gesture to repel the jets. Then we walked home in a daze, my legs rubbery, and found that the bombs had missed our home, but only narrowly. They had detonated at a nearby school.

~~~

At each temporary place of refuge, my parents tried to secure a small farmland. They sowed yam and cocoyam and also grew a variety of vegetables. We, the children, scrounged around for anything that was edible, relishing foods that in less stressful times would have made us retch.

One of my older cousins was good at making catapults, which we used to hunt lizards. We roasted them over fires of wood and dried brush and savored their soft meat. My cousin also set traps for rats. When his traps caught a squirrel or a rabbit, we felt providentially favored. Occasionally he would kill a tiny bird or two, and we would all stake out a claim on a piece of its meat.

While my family was constantly beset by hunger, we knew many others who had it worse. Biafra teemed with malnourished kids afflicted with kwashiorkor that gave them the forlorn air of the walking dead. Their hair was thin and discolored, heads big, eyes sunken, necks thin and scrawny, their skin wrinkly and sallow, stomachs distended, legs spindly.

As they ransacked the house, they kept my father closely in view. Then they took him away.

Like other Biafrans, we depended on food and medicines donated by such international agencies as Catholic Relief and the Red Cross. Sometimes I accompanied my parents on trips to relief centers. The food queues, which snaked for what seemed like miles—a crush of men, women, children—offered less food than frustration as there was never enough to go round. One day, I saw a man crumble to the ground. Other men surrounded his limp body. As they removed him, my parents blocked my sight, an effete attempt to shield me from a tragedy I had already fully witnessed.

Some unscrupulous officers of the beleaguered Biafra diverted food to their homes. Bags of rice, beans and other foods, marked with a donor agency’s insignia, were not uncommon in markets. The betrayal pained my father. He railed by signing and distributing a petition against the Biafran officials who hoarded relief food or sold it for profit.

The petition drew the ire of the censured officials; the signatories were categorized as saboteurs. To be tagged a saboteur in Biafra was to be branded with a capital crime. A roundup was ordered. One afternoon, some grave-looking men arrived at our home. They snooped all over the house. They turned things over. They pulled out papers and pored over them, brows crinkled half in consternation, half in concentration. As they ransacked the house, they kept my father closely in view. Then they took him away.

Father was detained for several weeks. I don’t remember that our mother ever explained his absence. It was as if my father had died. And yet, since his disappearance was unspoken, it was as if he hadn’t.

Then one day, as quietly as he had exited, my father returned. For the first—and I believe last—time, I saw my father with a hirsute face. A man of steady habits, he shaved everyday of his adult life. His beard both fascinated and frightened me. It was as if my real father had been taken away and a different man had returned to us.

This image of my father so haunted me that, for many years afterwards, I flirted with the idea that I had dreamed it. It was only ten years ago, shortly after my father’s death, that I broached the subject with my mother. Yes, she confirmed, my father had been arrested during the war. And, yes, he’d come back wearing an unaccustomed beard.

~~~

Father owned a small transistor radio. It became the link between our war-torn space and the rest of the world. Every morning, as he shaved, my father tuned the radio to the British Broadcasting Corporation, which gave a more or less objective account of Biafra’s dwindling fortunes. It reported Biafra’s reverses, lost strongholds and captured soldiers as well as interviews with gloating Nigerian officials. Sometimes a Biafran official came on to refute accounts of lost ground and vow the Biafrans’ resolve to fight to the finish.

Feigning obliviousness, I always planted myself within earshot, then monitored my father’s face, hungry to gauge his response, the key to decoding the news. But his countenance remained inscrutable. Because he monitored the BBC while shaving, it was impossible to tell whether winces or tightening were from the scrape of a blade or the turn of the war.

At the end of the BBC broadcasts, my father twisted the knob to Radio Biafra, and then his emotions came on full display. Between interludes of martial music and heady war songs, the official mouthpiece gave exaggerated reports of the exploits of Biafran forces. They spoke about enemy soldiers “flushed out” or “wiped out” by gallant Biafran troops, of Nigerian soldiers surrendering. When an African country granted diplomatic recognition to Biafra, the development was described in superlative terms, sold as the beginning of a welter of such recognitions from powerful nations around the globe. “Yes! Yes!” my father would exclaim, buoyed by the diet of propaganda. How he must have detested it when the BBC disabused him, painted a patina of grey over Radio Biafra’s glossy canvas.

~~~

In January 1970, after enduring the 30-month siege, which claimed close to two million lives on both sides, Biafra buckled. We had emerged as part of the lucky, the undead. But though the war was over, I could intuit from my parents’ mien that the future was forbidden. It looked every bit as uncertain and ghastly as the past.

Feigning obliviousness, I always planted myself within earshot of the radio, then monitored my father’s face, hungry to gauge his response, the key to decoding the news.

Our last refugee camp abutted a makeshift barrack for the victorious Nigerian army. Once each day, Nigerian soldiers distributed relief material—used clothes and blankets, tinned food, powdery milk, flour, oats, beans, rice, such like. There was never enough food or clothing to go around, which meant that brawn and grit decided who got food and who starved. Knuckles and elbows were thrown. Children, the elderly, the feeble did not fare well in the food scuffles. My father was the sole member of our family who stood a chance. On good days, he squeaked out a few supplies; on bad days, he returned empty handed. On foodless nights, we found it impossible to work up enthusiasm about the cessation of war. Then, the cry of “Happy survival!” with which refugees greeted one another sounded hollow, a cruel joke.

Despite the hazards, we, the children, daily thronged the food lines. We operated around the edges hoping that our doleful expressions would invite pity. Too young to grasp the bleakness, we did not know that pity, like sympathy, was a scarce commodity when people were famished.

One day I ventured to the food queue and stood a safe distance away watching the mayhem, silently praying that somebody might stir with pity and invite me to sneak into the front. As I daydreamed, a woman beckoned to me. I shyly went to her. She was beautiful and her face held a wide, warm smile.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Okey,” I volunteered, averting my eyes.

“Look at me,” she said gently. I looked up, shivering. “I like your eyes.” She paused, and I looked away again. “Will you be my husband?”

Almost ten at the time, I was aware of the woman’s beauty, and also of a vague stirring inside me. Seized by a mixture of flattery, shame and shyness, I used bare toes to scratch patterns on the ground.

“Do you want some food?” she asked.

I answered with the sheerest of nods.

“Wait here.”

She went off. My heart pounded as I awaited her return, at once expectant and afraid. Back in a few minutes, she handed me a plastic bag filled with beans and a few canned tomatoes. I wanted to say my thanks, but my voice was choked. “Here,” she said. “Open your hand.” She dropped ten shillings onto my palm.

Too young to grasp the bleakness, we did not know that pity, like sympathy, was a scarce commodity when people were famished.

I ran to our tent, flush with exhilaration. As I handed the food and coin to my astonished parents, I breathlessly told them about my strange benefactor, though I never said a word about her comments on my eyes or her playful marriage proposal. The woman had given us enough food to last for two or three days. The ten shillings was the first post-war Nigerian coin my family owned. In a way, we’d taken a step towards becoming once again “Nigerian.” She’d also made me aware that my eyes were beautiful, despite their having seen so much ugliness.

~~~

Each day, streams of men set out and trekked many miles to their hometowns. They were reconnoiterers, eager to assess the state of life to which they and their families would eventually return. They returned with blistered feet and harrowing stories.

Amawbia was less than 40 miles away. By bus, the trip was easy, but there were few buses and my parents couldn’t afford the fare anyway. One day a man who’d traveled there came to our tent to share what he’d seen. His was a narrative of woes, except in one detail: My parents’ home, the man reported, was intact. He believed that an officer of the Nigerian army had used my parents’ home as his private lodgings. My parents’ joy was checked only by their informer’s account of his own misfortunes. He’d found his own home destroyed. Eavesdropping on his report, I imagined our home as a mythical island of order and wholesomeness ringed by overgrown copse and shattered houses.

The next day my father trekked home. He wanted to confirm what he’d heard and to arrange for our return. But when he got back, my mother let out a shriek then shook her head in quiet sobs. My father arrived in Amawbia to a shocking sight. Our house had been razed; the fire still smoldered, a testament to its recentness. As my father stood and gazed in stupefaction, the truth dawned on him: Some envious returnee, no doubt intent on equalizing misery, had torched it. War had brought out the worst in someone.

My parents had absorbed the shock of other losses. There was the death of a beloved grandaunt to sickness and of a distant cousin to gunshot in the battlefield. There was the impairment of another cousin who lost a hand. There was the loss of irreplaceable photographs, among them the images of my grandparents and of my father as a soldier in Burma during WWII. There was the loss of documents, including copies of my father’s letters (a man of compulsive fastidiousness, my father had a life-long habit of keeping copies of every letter he wrote). But this loss of our home cut to the quick because it was inflicted not by the detested Nigerian soldier but by one of our own. By somebody who would remain anonymous but who might come around later to exchange pleasantries with us, even to bemoan with us the scars left by war.

~~~

At war’s end, the Nigerian government offered 20 pounds to each Biafran adult. We used part of the sum to pay the fare for our trip home. I was shaken at the sight of our house: The concrete walls stood sturdily, covered with soot, but the collapsed roof left a gaping hole. Blackened zinc lay all about the floor. We squatted for a few days at the makeshift abode of my father’s cousins. Helped by several relatives, my father nailed back some of the zinc over half of the roof. Then we moved in.

This loss of our home cut to the quick because it was inflicted not by the detested Nigerian soldier but by one of our own.

The roof leaked whenever it rained. At night, rain fell on our mats, compelling us to move from one spot to another. In the day, shafts of sunlight pierced through the holes. But it was in that disheveled home that we began to piece our lives together again. We began to put behind us the terrors we had just emerged from. We started learning what it means to repair an inhuman wound, what it takes to go from here to there.

In time, my father was absorbed back into the postal service. My mother returned to teaching. We went back to school. The school building had taken a direct hit, so classes were kept in the open air. Even so, our desire to learn remained strong. At the teacher’s prompting, we rent the air, shouted the alphabet and yelled multiplication tables.

Okey Ndibe is the author of Arrows of Rain, teaches fiction and literature at Trinity College in Hartford, CT, and is finishing work on foreign gods, inc. Ndibe has also taught at Connecticut College in New London, CT. He was for one year on the editorial board of the Hartford Courant and, from 2001-2002, was a Fulbright professor at the University of Lagos, Nigeria.

To comment on this piece: editors@guernicamag.com