When we see a Syrian body today, it’s usually emerging from rubble, bloodied and stripped, or worse, already dead. If Syrians are not represented as victims of war, they appear as refugees in foreign lands, awkwardly juxtaposed with locals or aid workers. Beyond the tragic photograph, what do we ever learn about their bodies, or their lives? And why do we get a front seat to their agony? As if they haven’t lost enough, in a flash, they perpetually lose control over their own image.

In Displacement, a double-bill dance performance staged at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London this July, choreographer and dancer Mithkal Alzghair put the audience face to face with a moving Syrian body, and gave it the space to speak for itself. The moving, and at times unsettling, performance was part of London’s Shubbak Festival—a multidisciplinary, biannual arts festival that emerged in the expectant Arab Spring moment of 2011 with a vision to bring the most exciting Arab artwork to an international audience.

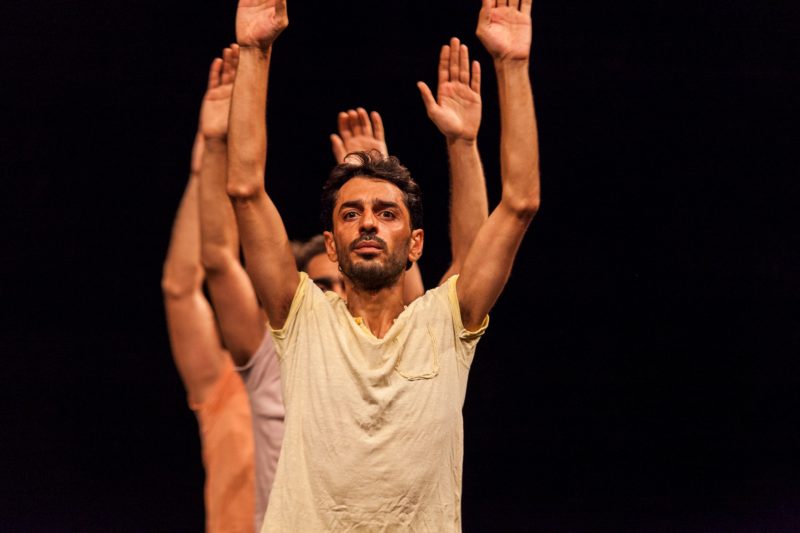

Alzghair, who trained in Damascus and then in Paris (where he currently resides), uses his body as a device to exhibit, explore, and challenge the various forces that have shaped the bodies and minds of Syrians in recent decades. In his solo sections, he moved intentionally and unexpectedly from one pose to another—a military stance morphed into a man in prayer. During the trio that followed, with Rami Farah from Syria and Samil Taskin from Turkey, they deconstructed popular Syrian folk dances, most prominently the Dabke, which features sophisticated footwork and stomping. Focusing on this traditional ritual was part of Alzghair’s attempt to decontextualize traditional cultural practices to pose the question: When the body is displaced, what goes with him, and what stays behind?

The Dabke is typically a boisterous affair, performed collectively at weddings or large parties. On the Sadler’s Wells stage, however, the dance does not take place amidst the rowdy milieu it usually arouses. There is very little music in Alzghair’s solo; a faint Syrian melody wafted through the air at various points, but the predominant sound the audience heard was that of the dancer’s deliberately labored breathing and his large black boots as they hit the wooden stage.

“I didn’t want music. I wanted you to see a body, listen to it breathing, and follow its every movement,” Alzghair told me at the sunny cafeteria at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre before his second performance. He looked exhausted—and he blamed it on spending the night before walking the streets of London, which he was visiting for the first time and had immediately fallen for. “I wanted to present something as real as possible,” he said. Before we parted ways so that he could do a quick yoga session and prepare for Displacement, Mithkal Alzghair talked to me about the process he went through to give creative form to his personal experience as a displaced Syrian.

—Sara Elkamel for Guernica

Guernica: Before we start talking about Displacement, I wanted to briefly ask you about Transaction, another performance you’re putting on in London as part of the Shubbak festival, this time with French dancers as well as Syrians. Will it be tackling the same topic?

Mithkal Alzghair: Which topic? (Laughs) No, Transaction is slightly different. Every project has a different physicality to it, and tackles different questions. But maybe some things intersect. In Transaction, we are talking about war, and specifically, the ways in which the body is represented in the context of war. It’s about the representation of the dead body, in reality and in the media, and in the history of art. It’s an installation performance, with bodies and objects laid out across the stage. But the show you saw yesterday, Displacement, was different. There were three bodies on stage, and it was all about their movement and rhythm.

Guernica: I’m sure you know Abounaddara, the anonymous Syrian filmmaker collective that has been posting short documentaries online every week since the revolution started, with the aim of offering an alternative view of Syrian society than the one represented in the media, which focuses solely on violence and warfare. It has been particularly vocal about this contentious issue of representing human bodies in the media in times of war. In an exhibition I saw in New York a couple of years ago, they were calling for the right to a dignified image, asking questions like, “Who has the right to the image? And once the body dies, how can it give consent?”

Mithkal Alzghair: Yes, exactly. You know, I was in Brussels recently, and I saw this installation composed of photographs of refugees —Syrians, Africans, a mix really. They were photographs of suffering children amidst different crises. The moments captured in these pictures were ones that anyone would normally want to hide from the world, for their vulnerability. So, a question emerges: who has the right to not only capture, but also exhibit these moments?

At the same time, such photographs may be the only way to represent reality. People can find out what’s happening in the world through the media, but art—a photograph, or dance, or music, or film—provides an alternative lens into what’s going on in the world. Still, that child whose photograph was exhibited in Brussels, and in other places, may grow up to feel robbed of his privacy in such a vulnerable moment—he never consented to his fragility being exhibited in that way.

Guernica: In your own work, and particularly with Displacement, is your intention to give audiences a window on what’s happening in Syria?

Mithkal Alzghair: Yes, of course. Ultimately, I feel that art has a lot to do with what’s going on in the world around you. So it is both private and public in scope. Because I started this project as a solo performance, I built it on my personal experience. In my solo, I tried to research how my body has been shaped. Like any Syrian body, it grew in a Syrian context, under dictatorship, a repressive education system, and military rule. I also wanted to research the political, religious and societal chains that have shaped our bodies. So that’s why I started to look into our folkloric dance, in an attempt to inspect the different ideologies – religious or societal or political or military—that have infiltrated our childhoods. I wanted to explore the freedom that a body has in this context of oppression.

I started the project with the word “displacement.” Maybe that’s because I had been experiencing it myself. I traveled to France voluntarily, to study choreography. When I finished, the war in Syria had started—what began as a revolution turned into a war—and I was being drafted for military service. My passport had expired, so I had the choice to either go back to Syria to serve in the military or to seek asylum in France. I knew I wanted to study dance, so I sought asylum in France. My legal status there had to be changed, and that took almost a year of paperwork and procedures. I was beginning to experience this displacement, and at the same time, Syrians at home were starting to go through it as well. It is not a novel or uncommon experience—and it may or may not be related to the context of war. We are sometimes forced to move, to leave everything we grew up, and go somewhere else. I started to ask myself: in this new context, in my new life in France, what is my identity, and what is left of my heritage?

Guernica: How did your creative choices in Displacement help you tackle such questions?

Mithkal Alzghair: I found that there were many things that needed to be torn down, and other things that needed to be built. I started to explore this dynamic of deconstruction and construction through movement. That’s why I attempted, in this piece, to surface symbols of the forces that have shaped us—including military and religious forces. And the repetition in the piece represents the resilience of these systemic forces.

I think of dance as a form of revolting. It is the body’s revolution, a protest. It is able to express this state of anger – I dance, I revolt.

I tried to show the body’s revolution, and the obstacles to this revolution. Perhaps I wanted to showcase the human being, without identification. This idea of displacement implies that we are arriving from our original culture to a host culture—so the way in which the other views us becomes important. So, okay, I am working on a project related to my culture and my people, but why don’t we bypass these conversations of culture, for the sake of a moment of human-to-human confrontation?

Guernica: There’s a lot of control in your solo, which contributes to this idea of dance as protest. You go from sitting on your knees in a posture associated with prayer, and then you abruptly switch to military movements, and then folkloric dance, and these patterns are in repetition, but you’re all the while in control, changing the shape of your body at will. Your choice to include elements of folkloric dance is intriguing—does it represent another one of these oppressive forces that have shaped Syrian bodies, or is it a symbol of joy and resilience?

Mithkal Alzghair: It all started with the word “displacement,” then I started looking for a framework. Sometimes you’re stuck somewhere, and you physically cannot leave it, but you can still move, through your imagination, for example.

I started with this idea of moving around in a space you cannot leave. I decided that the solo would take the form of a protest on stage, in the presence of an audience. I chose this face-to-face form, with my gaze directed straight at the audience. I tried to work with the actual context of an audience that arrives to attend a dance performance. I am dancing for them, entertaining them, but I am providing a dance that is related to my identity. I settled on this folkloric dance, which is local to Syria but also to other countries, such as Palestine and Jordan. And you also find similar forms in Turkey and Greece. Even in parts of France, they have similar dances.

I researched different styles of Dabke to explore and analyze the context behind their final forms. For example, in the city of Sweida, where I’m from, the dancers come very close to the ground as they perform—there is an observable relationship with the roots. Meanwhile, when Palestinians dance the Dabke, it is as if they are floating; their feet are very light on the ground. Maybe that’s because they’ve experienced a life of displacement.

That’s how I came to this decision to take elements from two different folkloric dances: one of them was the Dabke, from which I borrowed the footwork and stomping, and then the other traditional dance people perform in Syria, called Lawha, supplied the arm-waving movements. But I adapted the Lawha dance so that the hands are truly reaching towards the sky, while in the original dance they are kept closer to the body. But I tried to lift them up much further.

I wanted to work on manipulating the outward image of the body, and on creating very subtle movements that could radically change the meaning. That’s why I went for this minimalist style—to leave room for multiple interpretations of the body’s image. When I am on my knees, you may see an image of someone mid-prayer, but I might see him as a prisoner, coerced by a soldier to kneel and raise his hands, with a weapon over his head—because right before then I was dancing in military style. But neither is correct—there could be more than one meaning.

Guernica: I found your face to be very blank throughout—your body was moving incessantly, but your expression was not. It was as if, like the audience, you were watching yourself.

Mithkal Alzghair: My facial expressions were a product of improvisation. I always open myself up to a relationship with the audience—my facial expressions are always tied to the movements my body is making. I let the energy of the movements and my relationship to the audience manifest on my face.

When I perform this piece, there are always a lot of references on my mind, including photographs I have seen of Syrian bodies. But [I am thinking about] the present as well. So there are references in the background, and then there is what is happening [in the moment], what is being shaped now.

Guernica: What have you learned about your body over the past few years, particularly since you’ve started to produce work that is related to Syria or to the war?

Mithkal Alzghair: When I first started dancing in Sweida, I did classical and modern dance, and then I discovered the contemporary style. I used to love the energy and the dynamic movement that dance afforded me. But perhaps after the war started, I started to become calmer and more rooted to the ground. I started thinking of dance as an art form—and there are responsibilities that come with making art. When you’re making art, before you start to move your body, you need to ask yourself: Who are you? Why? How? So there are many questions that I now need to ask myself before I start doing anything.

Guernica: What do you think your responsibility is as a Syrian artist?

Mithkal Alzghair: I am trying to not think of myself as an artist. I am not hiding from identity, but I am striving for us all to escape labels and identities and nationalisms and ideologies. I feel that my responsibility is not simply to escape from all of that myself, but to open people’s eyes and invite them to collectively escape these things.

Guernica: But even if on stage, you manage to decontextualize the issue or deconstruct identity, this work is being presented to the audience as a performance about the Syrian war. The art world today is very much mediated by language. So there’s the performance, but then there is the discourse, conversations and texts around it. All work is packaged in some narrative. What does it mean for this choreography to be about the Syrian war?

Mithkal Alzghair: I think it was Gilles Deleuze who said that the way artists worked changed completely after World War II, and that the documentary movement flourished, all because people were more drawn to reality than fiction. This might be related to why this experience of war has made me feel that reality is so much stronger than fiction. And this might be why, in Displacement, I tried to tackle what’s real, or that which is related to who I am, my identity.

This was reflected in some of the creative choices I made. For example, I didn’t want music. I wanted you to see a body, listen to it breathing, and follow its every movement. I wanted to present something as real as possible.