Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

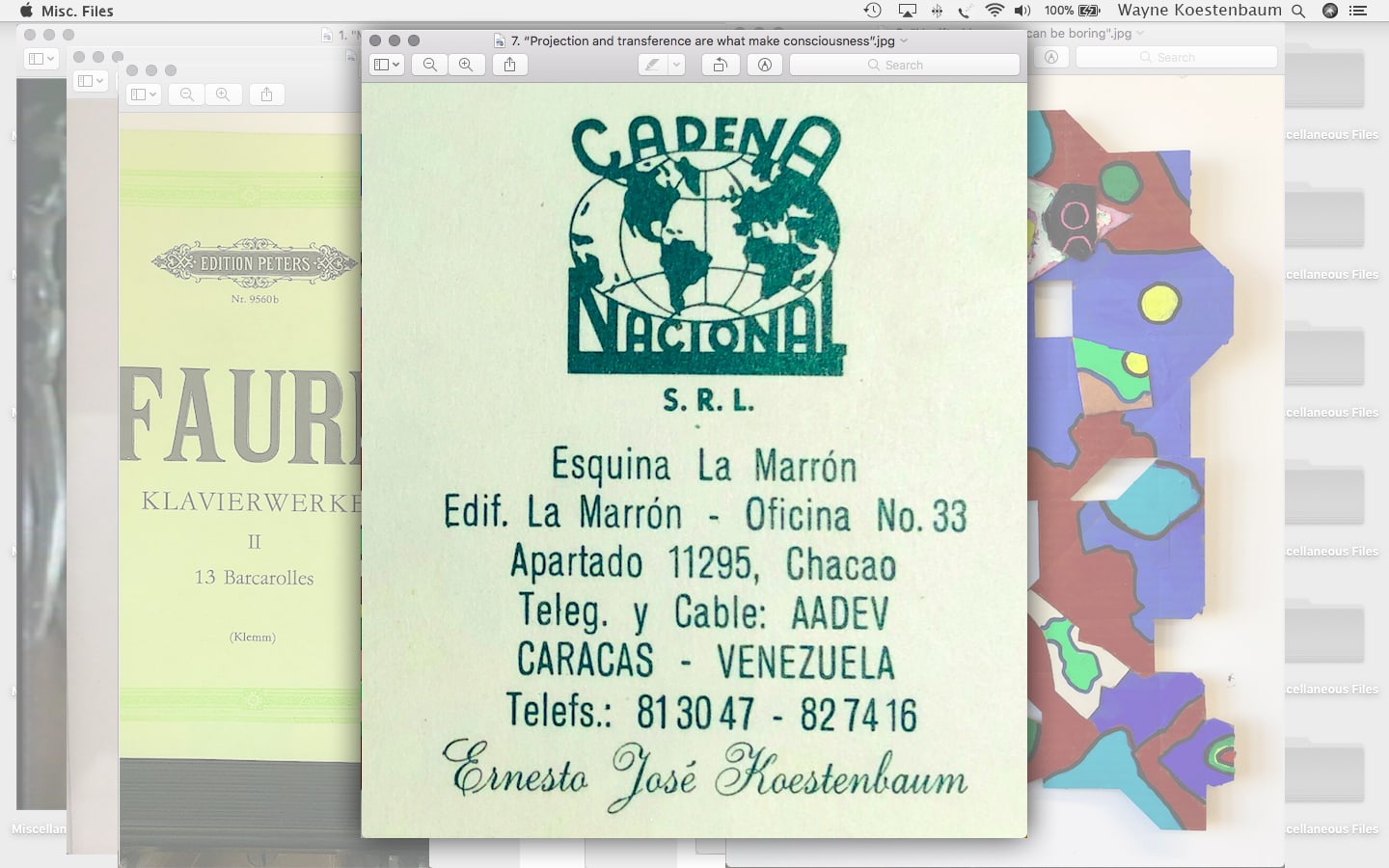

Wayne Koestenbaum began our conversation by asking about my name. I was quick to offer a brief summary of my peripatetic and bi-national family history: “I don’t have a solid, unequivocal mother tongue,” I told him, almost apologetically. Perhaps my confession was meant to assuage my anxiety of interviewing someone whose virtuosic and exacting prose is the expression of a lifetime commitment to a poetics of nuance. I needn’t have worried. In talking to Wayne, I learned that the expansiveness and eclecticism of his knowledge is also a form of generosity; He could meet me almost anywhere—an obscure literary reference, a debate about abortion, or a tangent about fandom. I certainly didn’t expect him to meet me in Caracas, a city, it turned out, where our vastly different lineages uncannily converge: My maternal country is where Wayne’s paternal grandfather landed after fleeing Nazi Germany.

For the past two years, Wayne has been processing his archives, gathering and indexing unpublished prose, poetry, notes, and family-related documents that he occasionally dispatches on Twitter. Broken and disenfranchised lineages elicit speculation; learning more about one’s personal history of migration, and the tangled ways the self is formed over generations, is a narrative exercise—and a fertile ground for fiction. Wayne rarely writes fiction, but when he does, it is exquisitely unhinged, a little more so than the rest of his more typically aphoristic prose. Although grouping Koestenbaum’s nineteen publications under a single genre wouldn’t do justice to the formally diverse span of his literary production, his writing is undeniably essayistic– a mélange of cultural criticism, homage, and autobiography in close conversation with authors like Susan Sontag, Richard Howard, or Robert Walser. Narrative continuity and formal completion aren’t exactly his bedfellows, which is why Circus, a novel, stands out among the rest of his oeuvre. First released in 2004 as Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes—Circus touches on some of his customary themes: family and psychoanalysis, public sex, classical music. Set in East Kill, New York, the novel chronicles Theo Mangrove’s forthcoming musical comeback in Aigues-Mortes, Southern France, where he desperately hopes to be joined by the Italian circus diva Moira Orfei. Decadent, damaged family relations shape the protagonist’s world: a domineering mother who is a successful pianist, a reclusive sister, and an intellectual aunt who Theo has sex with when he isn’t roaming East Kill’s waterfront to alleviate yet another erection. Composed as a series of notebooks authored by the narrator, Circus logs the highs and lows of Theo Mangrove’s small-town life and histrionic musical aspirations. His accounts are detailed, raw, and sexually explicit; as Theo’s HIV positive body gradually deteriorates, he ruminates obsessively over a classical repertoire that he may or may not perform.

Our conversation moved between the page and the world, outlining the book’s genesis and the anatomy of its influences. A back-and-forth that felt to me something like a dreamscape—traversing geographies from Caracas to East Kill via Aigue-Mortes and San Jose and traveling in time from the early ’90s of the novel, to its first release in 2004 and its forthcoming re-issue this summer. Talking to Wayne was like being in a trancelike state in which neither fiction nor life took precedence. Rather, they established a coexistence in which genres and categories began to dissolve.

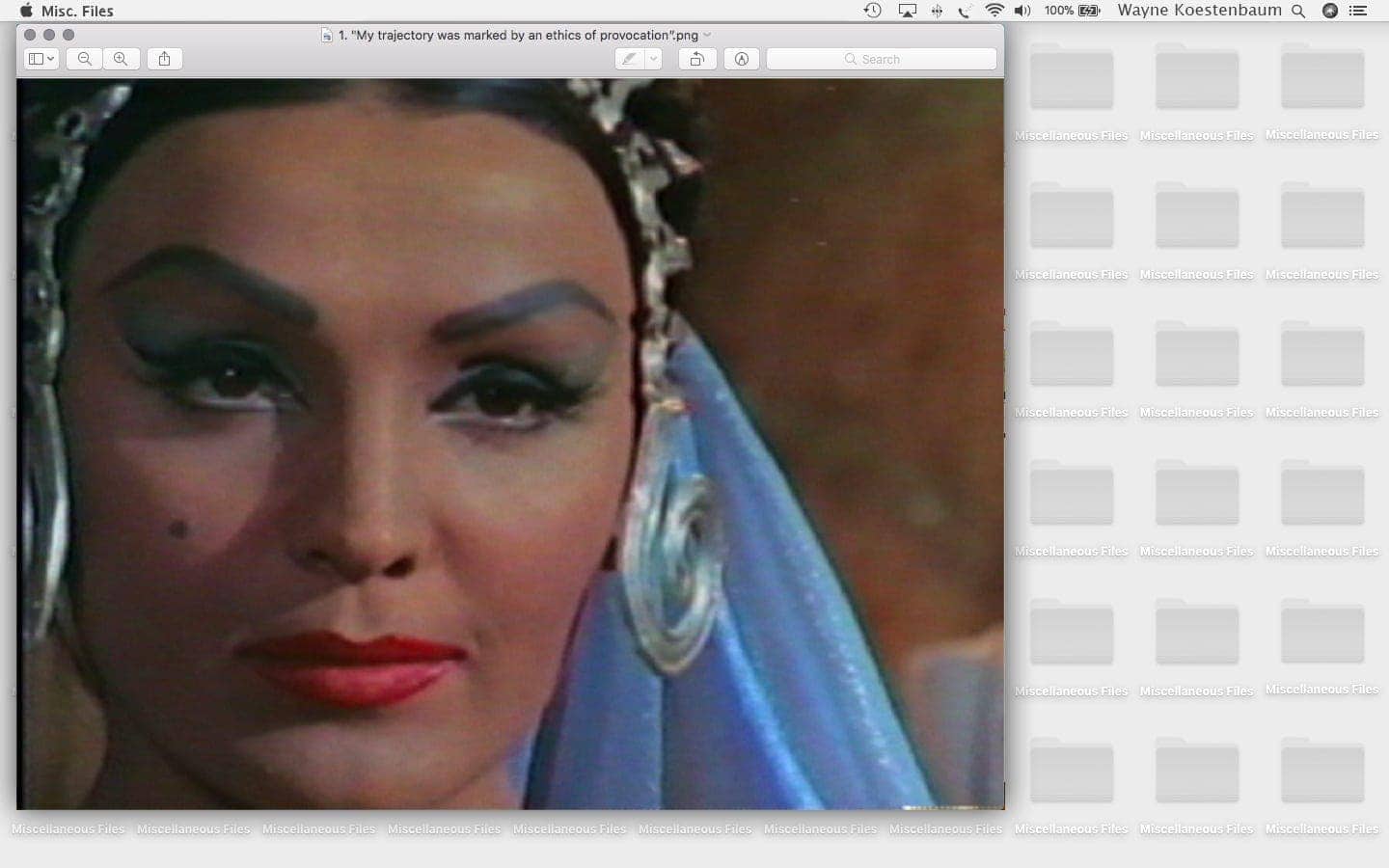

1. “My trajectory was marked by an ethics of provocation.”

Wayne Koestenbaum: The first visual image at the origin of the book is a poster of the Italian circus diva, Moira Orfei. I went to Italy in 1985, for the first time. Traveling around Tuscany and the Veneto region, I saw these posters everywhere, and finally, I stopped our little rental car on a country road (near Montecatini Terme?) and I took down a poster to keep as a souvenir. That Moira Orfei poster has been on my office wall since 1988. When I started writing the novel, it wasn’t a novel at first, but a series of notebooks about playing the piano; I spoke in the voice of an imaginary pianist who lived in upstate New York and who began dreaming of a comeback with Moira Orfei.

Mirene Arsanios: In the introduction to the book, Rachel Kushner mentions that she heard you read from Circus in 2004, which is when the novel first came out, then under the title Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes. Are these two editions the exact same book?

Koestenbaum: Yes. If I were to rewrite it, I wouldn’t even know how. Would I make it more plausible? Would I make it less obscene? If I even slightly began to touch it, I fear I’d make it less obscene.

Arsanios: Why?

Koestenbaum: I use “obscene” as a term of praise. When I wrote the book, I was conscious of working within the tradition of Marquis de Sade or of Dennis Cooper, who is a very important writer to me. My generation and my personal trajectory were marked by an ethics of provocation and transgressive performance art; shock art was part of my time. 1988 was the year of the NEA Four [four performance artists whose work was denied funding from the National Endowment of the Arts because of a newly passed “decency clause”]. I had just gotten my Ph.D. and was beginning to write avowedly queer books. My whole aesthetic—and the urgency of that moment—gave priority to the unashamed voicing of erotic undergrounds.

Arsanios: Was that urgency a form of militantism?

Koestenbaum: It is also farcical. In the novel, at least. It’s not a liberatory, triumphant eroticism. It’s a comic eroticism.

Arsanios: Do you still feel the same kind of erotic urgency today?

Koestenbaum: AIDS at first seemed to complicate the ethos of unproblematic liberatory eroticism. Remember, the debates about whether bathhouses should be kept open? Those debates are the seedbed for this novel. In the ’80s, radical queer thought converged with pro-sex feminism around the pornography wars. Despite misogyny and AIDS, it was important for us to remain attuned to the pleasures and the display of the body. Around the 2000s, for me at least, that stance seemed to erode from within, or to grow more complicated. I’m not a historian, but let’s say, perhaps rashly, that priapism became less transgressive. I was always interested in rewriting the male body: invaginating it, enmeshing it, aerating it, dispersing it, faux-castrating it; reupholstering was always part of my program. (By the way, even the incest in Circus, which moves against normative notions of the family, seems more shocking to me now, when I reread the novel, than when I first wrote it.)

Arsanios: Eroticism today seems absent from the public sphere. It’s more segregated or confined to dating apps, as if desire has been entirely privatized.

Koestenbaum: I’ve been anti-privatizing from the get-go. The arguments about public sex and its importance are crucial to this book. Circus and classical music performance are rarefied and sacramental forms of public sex. One of the pleasures of the book is conflating the circus and classical music, which ostensibly have nothing to do with each other. Being pathetic and being world-famous. What is a career in East Kill? How is that even a possibility? There’s no East Kill Lyric Opera, no East Kill Conservatoire. No small town has a European, metropolitan cultural scene that resembles the one I describe in the book.

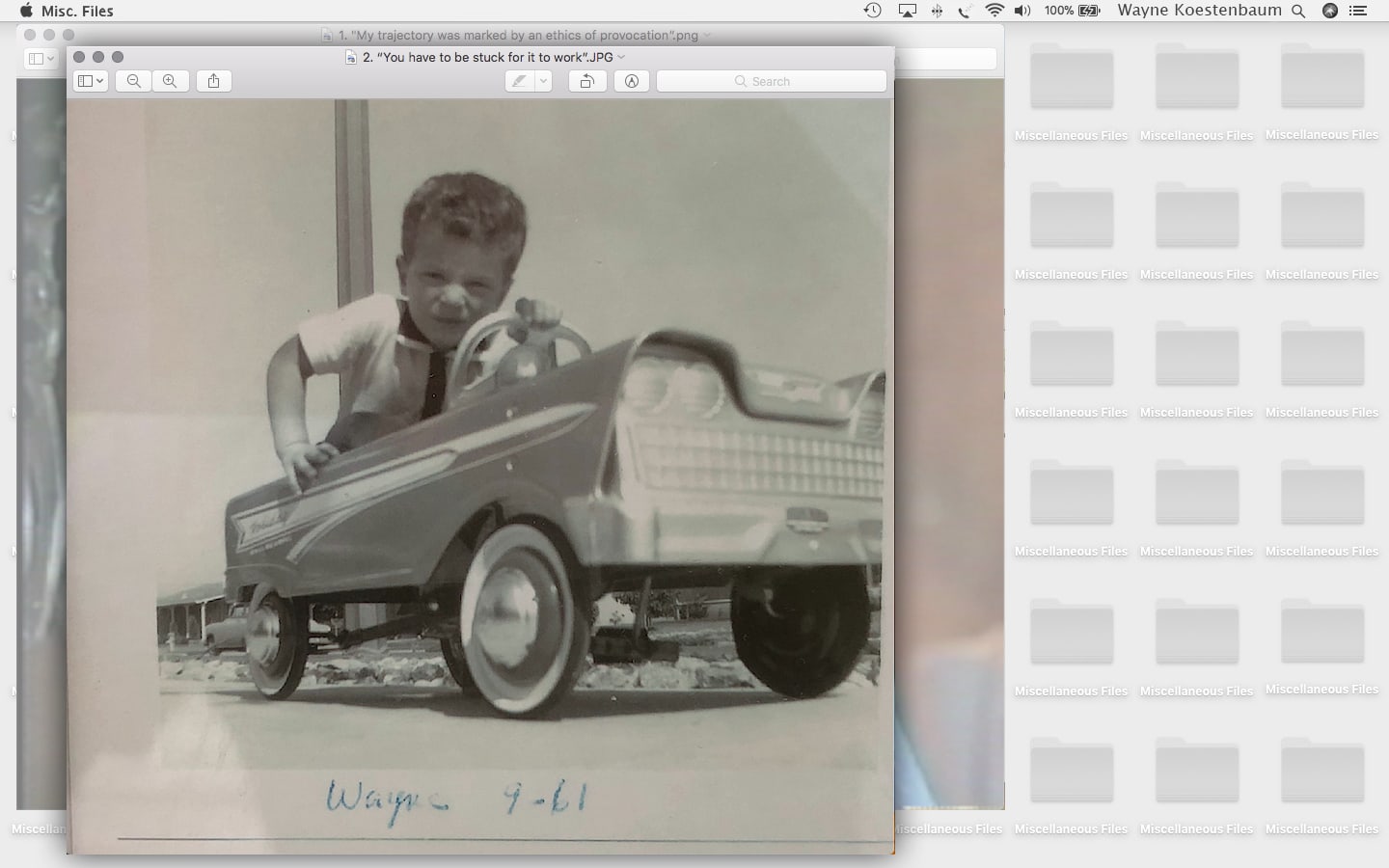

2. “You have to be stuck for it to work.”

Arsanios: What attracts you to this kind of provincialism?

Koestenbaum: I love it. When I get the novel fever in me, it always has to do with a grandiose, erotico-moniacal life led in an implausibly parochial American town. The combination of a small, culturally impoverished community and flamboyant grandiosity comes from growing up in suburbia. I was born in 1958 in San Jose, and the cultural scene in the landscape of the little area where I grew up was fairly parochial. Here’s a picture of me in a toy car outside my house, circa 1961. I appear to be squinting, because of the bright California sunlight. I was shaped by the block I grew up on. There were still orchards in San Jose where I used to go with my brother, looking for mysteries. I remember when the first shopping mall opened and the first McDonalds. It was all very “small town.” San Francisco was impossibly far away.

Arsanios: But the world enters East Kill. Theo’s family is deeply connected to a history of art making and world traveling, with Alma’s frequent trips to Buenos Aires and Theo’s European meanderings.

Koestenbaum: I was thinking of Joseph Cornell. I wrote a prequel, an unpublished novel called Tiny—My Mother’s Rules was another title—which is about a Joseph Cornell-like figure. Cornell lived in Flushing, New York with his mother and his brother, and he took exploratory trips into New York and constructed a fantasy art that was based on European surrealism but that was really located on his kitchen table. The family structure in Circus is indirectly inspired by Cornell’s Christian Science mother and his disabled brother. That vision of how artistic avant-gardes make their queer and circuitous way into parochial American milieu influenced the writing of Circus.

Arsanios: You’ve engaged the notebook in your previous essayistic and poetic writings, but never through fiction. What kind of world is the fictional notebook able to conjure?

Koestenbaum: Robert Walser’s fictional essays and lyric flights, which come from a place of grandiosity and abjection, were an important influence when writing Circus. Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet was also an inspiration, in particular, his fictional narrator, Bernardo Soares. Other works that stimulated me include Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Bridge, and Thomas Bernhard’s novels, which are not really notebooks but first-person rants. These writers take the megalomania and abjection implicit in diary-writing and magnify both extremes. The plot of such novels often involves mediocre and unfortunate locales. It doesn’t work if you’re a jet setter. You have to be stuck for it to work.

Arsanios: Would you say that fictionalizing the notebook allows for an exploration of consciousness that wouldn’t have been accessible otherwise?

Koestenbaum: Fiction was the first genre I wrote; I wrote fiction in college, and I got an M.A. in fiction-writing. The voice I use when I write third-person fiction is still immature, like that college kid’s. I dropped conventional fiction because it felt like a straitjacket. With poetry and essay, I could be more grown-up. What is your primary genre?

Arsanios: I move in between, but I mainly write fiction. I also write essays and prose. I can’t really commit to a single genre.

Koestenbaum: Do you find a difficulty in letting in your full self with fiction, linguistically speaking?

Arsanios: Absolutely. I’m constantly fighting myself when writing fiction. I pause to diagnose the prose when it feels stiff or when a situation is being described from an abstracted “outside.”

Koestenbaum: How do you do that?

Arsanios: By reminding myself to reinsert and reassert the body or some form of desire in the prose. How can the writing not be flat?

Koestenbaum: Yeah, my fiction was flat.

Arsanios: But Circus isn’t flat at all!

Koestenbaum: That’s because it’s closer to my poetry and my essays. I learned, in writing Circus, how to revise fiction.

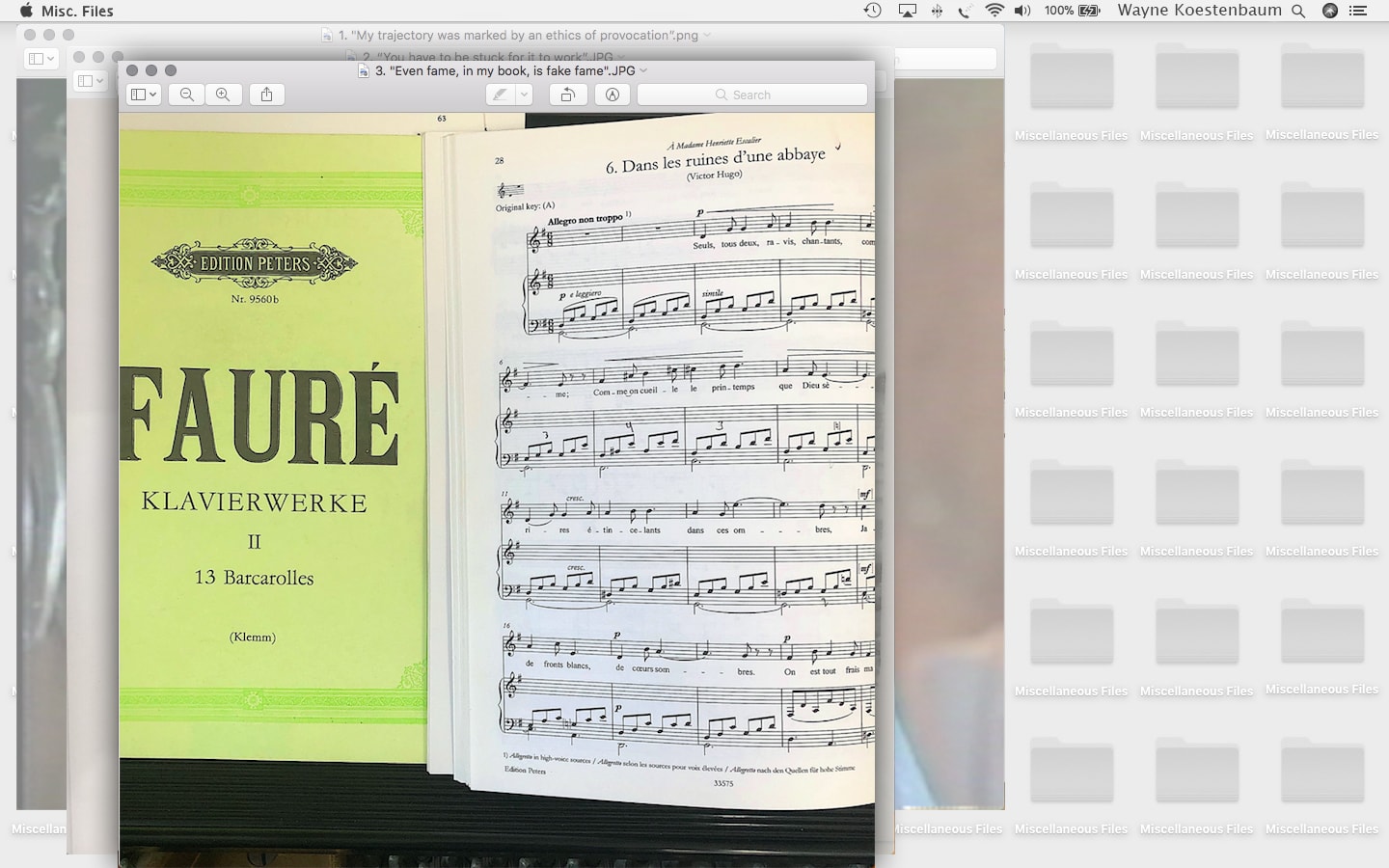

3. “Even fame, in my book, is fake fame.”

Koestenbaum: The image on the right-hand side is the score to a Gabriel Fauré song, Dans les ruines d’une abbaye (“in the ruins of an abbey”). I was learning this song at the time that I began my first Instagram account, and so I chose “dans_les_ruines” as my screen-name, in homage to this song. On the left-hand side of the piano music stand is the score to Fauré’s Barcarolles for solo piano, which are pieces I happened to be playing this week, when I took the picture.

Arsanios: Theo is an extremely complex character. He has the ability to process complicated relationships with his mother, sister, and broader entourage in highly analytical ways, combined with straightforward observations about sex and the everyday. He’s able to accommodate multiple ways of thinking.

Koestenbaum: He’s sort of an idiot savant. He has a flat affect, which always interested me in literature, though not in life.

Arsanios: While reading the book, I was thinking of all the potentially traumatic events Theo was subjected to: illness, family abuse, incest. Yet he is able to put all of it into language. Things just happen to him, without drama. His wounds aren’t bound to a history of abuse. The most anxiety-driven event in the book is the concert he’s preparing for.

Koestenbaum: In writing, I’ve always tried to figure out this funny blend of flattened relations to traumatic events, combined with a heightened valorizing of performers, singers, and movie stars. Fiction, as opposed to essays and poems, allows me to present that flattened relationship to trauma. It felt so authentic to be that person who could report a traumatic incident and find it either funny or a non-event. That emotional structure, in a way, reflects my life. We all have our own stories and personality structures. This book is a portrait of how various forms of historical and psychological trauma create art making and a sexual marketplace, a field of private and public sexual relations crisscrossing the family.

Arsanios: Your novel uses the first person without giving into the mythology of a highly individualistic or capitalist sense of self. Theo’s “I” isn’t solipsistic, rather, it is directed outwards, towards others—family member, Moira Orfei, or his multiple lovers. What happens to him also happens to others—illness, for example, seems to be a shared condition. I guess I’m connecting the celebration of the first person, its likability and deep psychology, to a type of American fiction in which the narrator becomes center stage at the expense of a broader social sphere. Whereas in Circus, Theo is always traversed by or traversing others.

Koestenbaum: It’s faux-capitalism. Theo’s fortune is agrarian, it comes from dairy farming. The farmers themselves are not capitalists. It makes narration easier if you have a financially secure narrator, almost like a feudal economy. Even fame, in my book, is fake fame. Moira Orfei is famous in Italy but she’s not internationally famous, and her fame is in the past. Aigues-Mortes is not Aix-en-Provence.

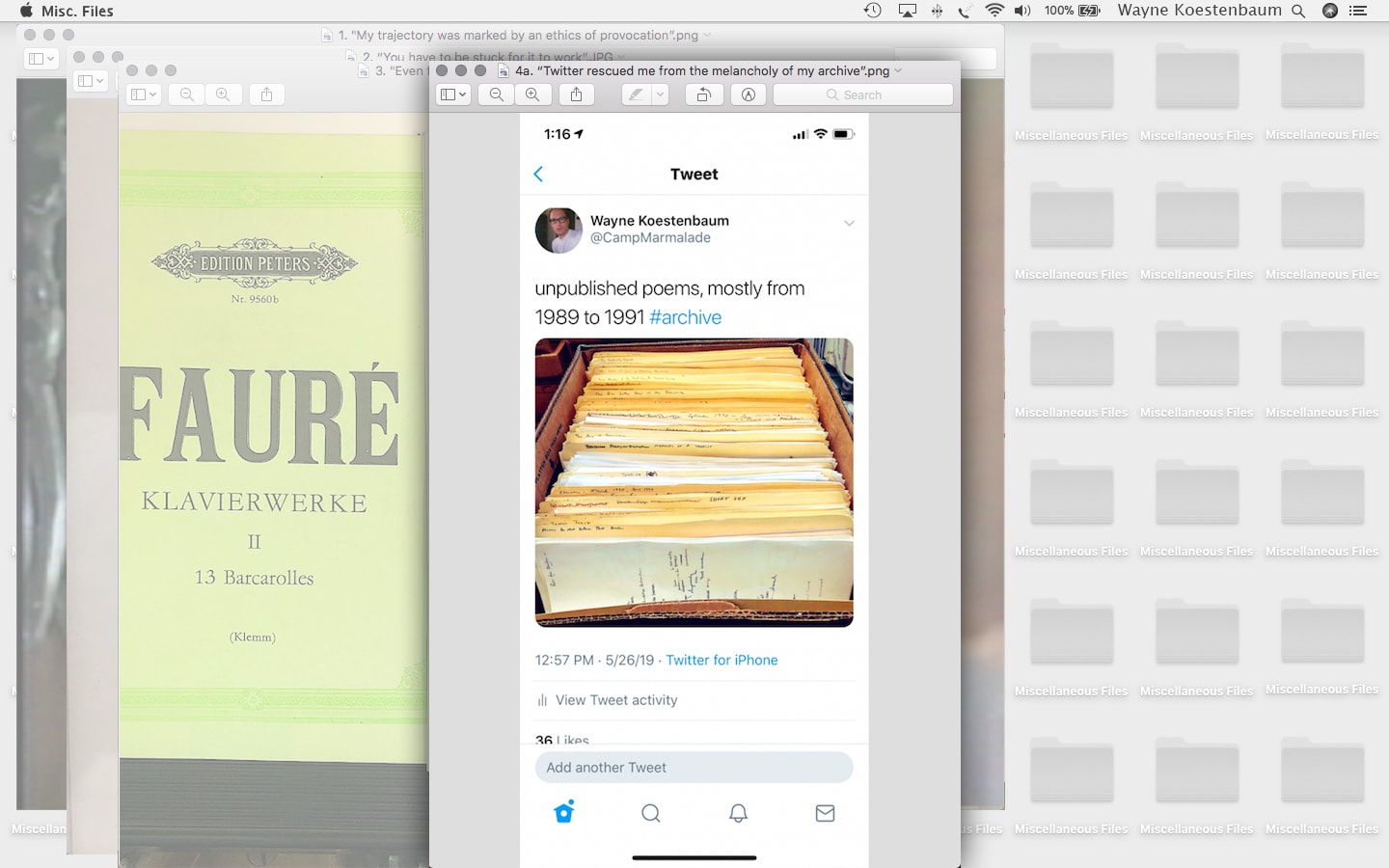

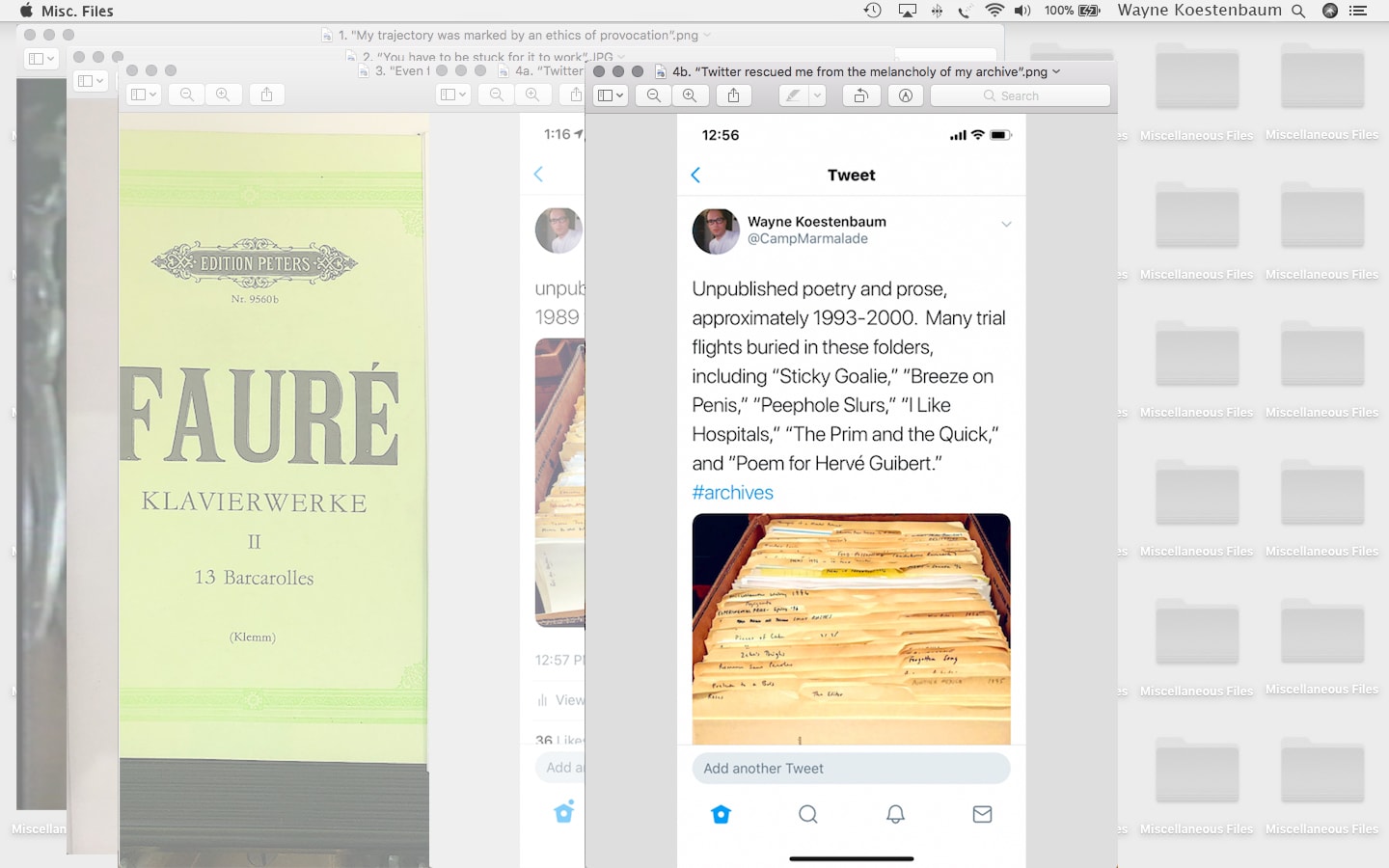

4. “Twitter rescued me from the melancholy of my archive.”

Koestenbaum: I’ve been processing my archive in the last two years, including family memorabilia, and it strikes me that my paternal grandfather, whom I never knew, might have had some Theo Mangrove in his personality. I found letters my grandfather wrote in German to my great-aunt, and they’re a little crazy, in a grandiose way. My father once told me that my grandfather, preposterously, wanted to set up him up with a coffee plantation in Caracas. Part of my DNA is a historically disenfranchised, psychologically damaged grandiosity. This might be why it was important for me to imagine certain kinds of foreignness combined with a strange, rural American town.

Arsanios: How are you processing your own archives?

Koestenbaum: My literary archives are going to Yale, to the Beinecke Library. Something like 140 boxes of published and unpublished writing and other personal materials; everything except for my diaries. In a year, my papers will be open to researchers. I’ve often suspected that my archive was more interesting than my writing.

Arsanios: Really?

Koestenbaum: Not that anyone would want to read every page of my drafts! That’s why I try to revise them into publishable books. I’ve always saved everything. There’s a kind of logorrhea involved in my hoarding of all these scraps of paper, and my life of compulsive composition.

Arsanios: What’s your relationship to digital, live archives like Twitter?

Koestenbaum: Twitter rescued me from the melancholy of my archive. I am no naive proponent of social media, and I was late coming to it, given my Luddite allegiances. I like the arts of the hand, and I like solitude and concentration. But in the last few months, I’ve been selecting material found in my archive, photographing it or transcribing it, and tweeting it. Tweeting literally brought these scraps into the world and gave them exponentially greater life than they ever dreamed of having.

I like tweeting little bits of the still-untitled third volume of my “trance trilogy” as I’m revising it. The audience for poetry, or for my poetry, is very small. If fifty people “like” a poem-fragment I tweet (whatever “like” means), that’s perhaps more than will ever read and absorb the finished, published poem. I find Twitter cathartic. I fear that eventually, I will have to leave it, maybe because I will get involved in some kind of feud that I just can’t cope with.

Arsanios: Do you also use Twitter for political commentary?

Koestenbaum: When I start seeing the news in the evening, there’s a feeling I try not to indulge in. I sometimes feel compelled to articulate both a rising of revolutionary fervor and a sense of disgust. At night, the Twitter feed makes me think that we’re at a major turning point, that there’s some breaking news that’s going to change everything. But by the morning, the revolutionary fervor is gone, and we’re back to the dismal situation.

Arsanios: Circus was written in the early 2000s but is set somewhere in the early ’90s, between the launch of the World Wide Web and the US war in Iraq. Yet, the book doesn’t engage its own present. Theo mentions, for example, that his country is bombing a foreign country without ever naming it.

Koestenbaum: One of the problems in this country is its blindness to history; a sense of being above history or of being the maker of history, but not actually implicated in it. Circus is not a historical novel. It’s writing the body and looking at the body for the signs of history.

Arsanios: At the same time, it’s a very cosmopolitan novel, full of worldly references. Perhaps that fantasy is also specifically North American, as you’ve mentioned before.

Koestenbaum: I’m thinking of artists like John Waters and Andy Warhol, but also of drag culture, where there is a stylization and freeze-framing of star culture—a fictional realm that is internal to gender and sexual position. Stardom is something we’ve interjected, something that constructs us, and something that we somaticize and spatialize, with gestures and asides and symptoms. Stardom is internal to the body.

5. “I’m basically improvising a poem to the camera.”

Koestenbaum: My first Instagram name was “dans_les_ruines,” and it was an anonymous account. It was very Theo Mangrove. I had very few followers, of course, and I made visual collages. Then I came out as me and started making videos, which I love.

Arsanios: Is that account still active?

Koestenbaum: Yes, but no longer as @dans_les_ruines; I’m @wayne.koestenbaum. For Instagram, I make videos of increasing complexity, and that’s become very liberating. I also do photo collages. I have a huge archive of Photoshopped images that I’ve made on my phone, with which I compulsively construct little animations to use as the background for my soliloquies. I was recently invited by Patty Gone at The Believer to make a longer film, Folie à Trois, for which I used actors for the first time. My relationship to social media is very personal and very happy.

Arsanios: In the book, you also mention that Theo Mangrove is considering projecting a Super 8 film with his performance.

Koestenbaum: My videos are actually very labor-intensive. I have to compose all the backgrounds, which are based on my paintings.

Arsanios: Are your videos scripted?

Koestenbaum: No. I’m basically improvising a poem to the camera. I have much more work than can ever be shown. This stack of drawings here, in my studio—the whole stack—is much more vital than one drawing seen by itself.

6. “Unsifted language can be boring.”

Arsanios: When writing, you produce a vast quantity of material that you edit down to the narrower form of the book. How would you compare your painting and writing processes?

Koestenbaum: Literature is different because the mind gets confused when the words aren’t sorted; unsifted language can be boring. I’m a careful reviser, and the words have to land in the right place. The process is the same with visual art, but it’s less laborious to see a painting than to read an essay. This is one of my works.

Arsanios: Contemporary art is so deeply commodified, but you’re producing all these paintings without a clear destination. There’s something radical in your approach.

Koestenbaum: It’s a little Theo Mangrove. I have a Mangrove-sized sense of artistic vocation. But I pray it’s not totally delusional.

7. “Projection and transference are what make consciousness.”

Arsanios: I think it makes sense that you’re finding a digital form for your artistic and familial archives and ways to have them intersect.

Koestenbaum: This enigmatic business card is among the few traces in my archive of my grandfather’s later life. I met him only once, and I have no memory of the encounter. He fled Germany, with my father and grandmother, by pretending to know Spanish and thereby getting promised a job in Caracas. He answered an ad that might have been philanthropically helping Jews leave Europe. He took a boat from Hamburg to Caracas; after my grandmother died, he married a woman named Carlota. I always assumed Carlota was from Venezuela, but I think she was originally Charlotte, from Berlin. For most of my life, I believed he’d married some glamorous Venezuelan woman named Carlota.

Arsanios: Did your father tell you all these stories?

Koestenbaum: Rarely. He would usually say that the past doesn’t interest him. The few things he said made a huge impact and are remembered forever: luminous facts. My father told me that when he left Germany, his family brought a Leica camera and a paltry number of German marks. That’s it.

Arsanios: My grandmother re-married after my grandfather was shot. I know very little about my grandmother’s lineage and have always wanted to know more. She was born in Curaçao but was from Coro, Venezuela. She was raised by her aunts and estranged from her mother. I’d like to travel to Curacao to further investigate my grandmother’s lineage. Both my mother and grandmother passed away. I cling on to these little details, objects, which I then write stories about.

Koestenbaum: You have so much to write about in your life!

Arsanios: Theo’s entire consciousness is defined by family relations. Family plays such a formative role in shaping one’s identity and sense of self. I’m wondering if reproductive technologies enabling gestation outside the parents’ biological bodies can undo conventional family roles. Are these new technologies also altering our psyche? Once lodged outside the biological mother/father paradigm, psychoanalysis might become obsolete.

Koestenbaum: There’s no escaping the undertow of transference, the depositing of internal stories and emotional valuations on external phenomena that don’t ask for such projections. Projection and transference are what make up consciousness. We project onto objects and people—the world we see is a reflection of our internal story. However, separate from the body and the mother or father, there is the fact of attachment. It could be to a raincoat. There will always be an animal, physiological, and neurological attachment that will produce learning habits and behavior patterns. And attachment creates scenarios. To bring it full circle to the story of the novel, I’ve always had an attachment to the piano, and writing this book was a way of acting out the nature of this attachment.

Arsanios: Can attachment accommodate multiple objects at the same time?

Koestenbaum: Music making (my “lounge act”) and performances in my videos have loosened and made variegated my attachment to the piano, less scripted along the lines of the punitive structures of Circus, performance traditions which are hinged to failure and a classical repertoire rather than to untethered improvisation. Maybe Theo won’t play a concert in Aigues-Mortes, maybe he will just improvise. Might that be more pleasurable for everyone? Maybe he’ll just talk, and Moira will play the piano.

Arsanios: Theo says in the book, “If, once, an audience reciprocated, I could permanently retire.” Does the loosening up of the repertoire invite more reciprocity at the cost of losing the obsessive attachment that defines Theo’s pursuit?

Koestenbaum: This novel was written in secret and in solitude and had its own peculiar little history. That the book is occurring in real time right now again, and (I hope) resonating in some people’s minds, is a fact I receive as an unexpected gift, a happy accident. It’s like discovering you had like a secret stash of treasure locked away somewhere, or a lost twin magically reappearing.