The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated existing crises in our systems, making the work of activists more urgent than ever. At the same time, concerns about public health and the resulting changes in behavior and regulation have forced many to reimagine the way they conduct their work. In this series of interviews, Miscellaneous Files asks activists and organizers around the world to share digital artifacts on their devices for insight into how they’re navigating this time of momentous change.

The first edition of this series features interviews with organizers fighting for racial justice. Below, you’ll find my conversation with Sylvana Simons, who in 2016 founded BIJ1, a political party in the Netherlands fighting for an anti-racist and de-colonial agenda. As one of the most visible Black voices in Dutch politics, Simons discusses the challenges she faces in political organizing and how her former career as a TV host informed how she engages with the media as a politician. I also speak with an Ugandan journalist, editor, and feminist activist Rosebell Kugamire about the connection between movements in the US and on the African continent. Finally, we hear from Amanda Adé, a Black-Irish podcast host and Black Lives Matter activist, about the overwhelming support the movement has received in Ireland and how her generation is defining what it means to be Black and Irish.

This week I also spoke to two racial justice organizers in the US, Cat Brooks and Eric Ward here. These conversations revealed how the struggle against racist violence is shared around the globe, and also highlight the creativity that fuels the work of these organizers in a changed and changing world. In conversations over the next months, Miscellaneous Files will imagine a shared conversation between those fighting different, but connected forms exploitation in their respective specialities and regions—even as it is increasingly conducted through Zoom meetings, Twitter-storms, and shared Google docs. When I asked Rosebell Kugamire what advice she would give people who aren’t able to engage online, she said, “Start where you are.” I hope these exchanges can show how, despite the necessity of remaining in one place, our footprint can leave traces in many others.

1. Sylvana Simons: “It’s always been very difficult for the Netherlands to acknowledge its own role and history in institutionalized racism.”

Mary Wang: Can you summarize the platform of Bij1, the political party you started?

Sylvana Simons: We’re an intersectional political party with an activist orientation. We’re a party of the people, and we take what’s on the streets to the national political stage. We stand for radical equality and economic justice, which we hope to achieve through solidarity. The first screenshot you see is of one of our digital get-togethers—which we started doing since the coronavirus hit—where we talk about everything from how members have been doing to the course of the party.

Wang: While Black Lives Matter originated in the US, it has grown significantly in the Netherlands, partially in conjunction with the protest against Zwarte Piet, or Black Pete, the blackface figure that traditionally accompanies the Dutch version of Santa Claus. What are some similarities and differences between the Dutch movement and the American one?

Simons: The overall objectives are very similar: to protest institutionalized racism and police brutality. People have tried to draw attention to police brutality in the Netherlands for a long time, which disproportionately affects people of color. But because it doesn’t occur to the same excessive degree as in the US, Black Lives Matter in the Netherlands has functioned mostly as an occasion for various activist groups to come together. That was the case until now, at least.

The scale between Dutch and American forms of organizing is also very different, though we’ve seen, through the most recent protests, that the movement is growing here. I’m amazed at how the Dutch media has reported for weeks that there have been more people at the protests than expected. It indicates that both the authorities and the organizers have yet to believe there’s such widespread support. But it’s about time we adjust our expectations.

Wang: From what I’ve read, it seems that much of the Dutch media primarily sees it as a story about the US and American issues.

Simons: I see some reporting on the US, but not all. I see very little about police brutality and the way Trump intervenes, but I see some stories about the looting and the instances where it spins out of control. The reporting is quite partial and superficial. It’s always been very difficult for the Netherlands to acknowledge its own role and history in institutionalized racism. It’s a typical response, claiming it’s about other countries, not us.

Wang: You entered politics in 2016. At the time, the debate around Zwarte Piet was widely reported on in the international media, and you experienced many racist attacks after you spoke out against it. In the years since you’ve worked as a politician, have you noticed any changes in the Dutch attitude against racism?

Simons: It’s very special to see a growing group of Dutch people understand that we need to say goodbye to this caricature. More and more regional governments are banning Zwarte Piet, which is very encouraging. Just a few years ago, there was doubt about whether racism even existed in the Netherlands. Now there’s no way to deny it anymore. We’re making big strides, but just because we’ve won battles doesn’t mean we’ve won the war. I’m happy that our prime minister has finally spoken out about Zwarte Piet, but what is he going to do about the racism in the country? In its institutions? In his own party?

Wang: You recently called for more Black politicians to be elected. On the national level, there are no Black representatives in the current House of Representatives or the Senate, which together contain 225 seats. There are 16 with an immigrant background, however. What are some possible explanations for this underrepresentation, and what can be done to change it?

Simons: I was simply pointing out that we don’t have Black politicians on the ballot now, and in the cases where they were on the ballot, they were listed so low that there was little chance they would get elected. In our system, you’re going to need a lot of extra votes to enter the House that way. [Dutch ballots feature lists of candidate MPs of each party, with the party-leader at the head. Those listed lower on the ballot need extra “preference votes” to move up the list and win a seat in parliament.] Diversity has to become a matter of urgency for political parties in a structural way. Our party doesn’t have a separate department for diversity, because everything we do is seeped in the conviction that we don’t talk about people, but with people. That means we need diverse representation within our party. I don’t think skin color alone means adequate representation, but it helps. People also have to stand up and dare to take on certain jobs. And lastly, we shouldn’t shy away from embracing a Black agenda in the Netherlands. We’ve grown up with the idea here that everyone is equal, so if you ask for special rights, it means you’re taking something away from another. But to make up for everything that’s been missing for the Black and Afro-Caribbean communities, we have to formulate a Black agenda.

Wang: I read a newspaper article suggesting that part of the reason more Moroccan and Turkish representatives have been elected is because their communities are more strongly organized than the Black community.

Simons: I can imagine that being the case, as Black people in the Netherlands don’t live under one flag. They often have very different countries of origins and histories of migration, so the Dutch Black community consists of people from Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles, Ghana, Nigeria, Cape Verde, and many more places, and I would count the Moluccans and other people from Asia, too. They’re not organized around one religion or nationality, which is very different than those who moved to the Netherlands as migrant workers from Turkey and Morocco. They arrived around the same time and for the same reason, and they might also share certain cultural overlaps, like a mosque.

Wang: You started your career as a TV host. Has that experience affected your work as a politician, especially now that media and social media are so important to both politics and activism? And in that area, what are some of the strategies or initiatives you find exciting?

Simons: There are certainly overlaps between the two types of work—they both involve theatrics! But yes, my work as a TV host has given me a big platform. That makes it easier, even though my words get twisted. My role now is very different—I was on the one side of the table and now the other. I’m being approached differently, too. As an entertainer, there’s a lot you can say, but if you go on and start your own political party, people will suddenly see you as someone they have to reckon with. I know all the tricks, so I have no problems in dealing with the media. I hear from a lot of white people that they find the website withuiswerk.nl [translation: whitehomework.nl] a very valuable way to get tips for furthering their anti-racism and to understand what kind of homework they can do.

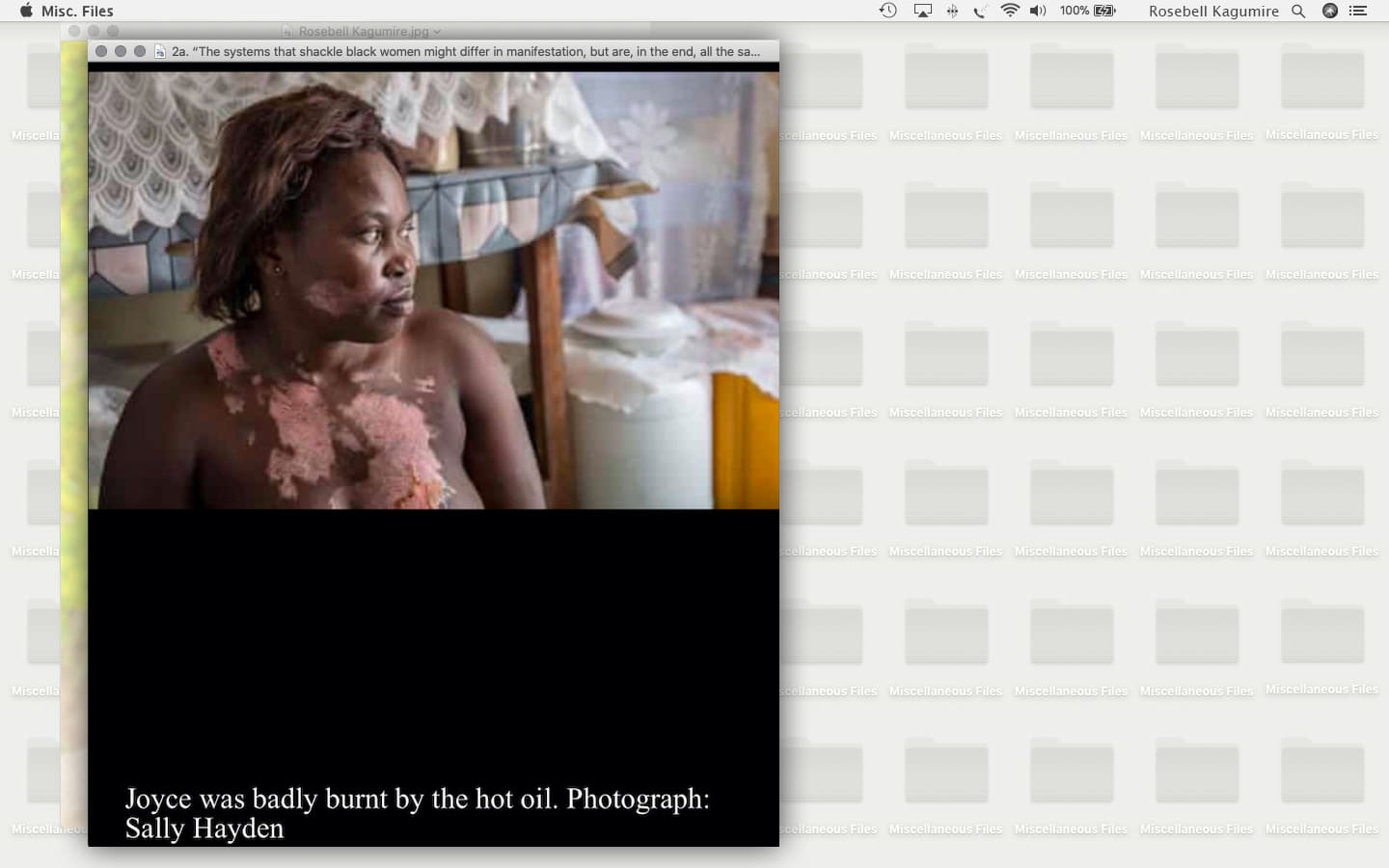

2. Rosebell Kugamire: “The systems that shackle black women might differ in manifestation, but are, in the end, all the same.”

Wang: What are we seeing in these screenshots? How do they relate to your work as a journalist and activist?

Kagumire: These screenshots show the struggle for Black women’s freedom in different localities. The first one is of a 31-year old street vendor called Alanyo Joyce whose chest is burnt. The photo was taken in Gulu, Northern Uganda, where the communities have barely gotten out of the woods after two decades of war. During the coronavirus lockdown, soldiers tossed a frying pan of boiling oil—which burned her—for not abiding by curfew guidelines. It shows what militarism does to women, society’s most vulnerable women specifically. The next screenshot is of academic and feminist activist Dr. Stella Nyanzi, who was dragged through the streets of Kampala, the capital, by Ugandan police for protesting the lack of emergency aid for poor and vulnerable families during the COVID-19 lockdown. The photo, captured by the brilliant photojournalist Sumy Sadurni, shows Nyanzi’s resistance even as she’s being dragged away. The last one is of a Black woman in America protesting racism and the continued murder of Black people. All these women are fighting related oppressive systems. Nyanzi’s protest and the state’s silencing of her actions are linked to Joyce’s struggle and attempt to make a living during a pandemic. The women in Uganda are battling a leftover colonial system and its legacy of policing Black bodies in Uganda even though the white colonists are long gone. The imperial racist system that still takes Black lives in America is connected to global struggles. The systems that shackle Black women might differ in manifestation, but, in the end, are all the same. For a pan-Africanist, all these struggles are connected.

Wang: In a previous interview, you mentioned that your work for AfricanFeminism.com partially sprung out of your frustration with the coverage of African women in mainstream media, and the way most Africans still learn about what’s happening across the continent through Western outlets. How does AfricanFeminism.com engage with these issues?

Kagumire: I work with African feminist writers to advocate for the equality of African women, minorities, LGBTQ communities, and others forced to live on the margins. We look into ways African women are positioned at the intersection of various oppressive systems, and document how women are organizing and fighting back. The platform elevates women’s voices as experts of their own lives. African women are still marginalized, even when communities and states are designing solutions to women’s issues. Many generations of women have worked to make the full contributions of women more visible, and we hope to add to that. We have documented #ChurchToo in Nigeria as Nigerians pushed back against rape in churches, the Women’s March in Uganda, the #TotalShutdown movement denouncing all violence against women, and Sudanese women’s voices on the revolution, and many others.

Wang: How has the pandemic and the lockdown changed your work, particularly what you do online? And how would you advise those who have limited access to the internet during the pandemic to engage in activism?

Kagumire: This is a time of great distraction, disruption and distress. Working online isn’t the same when most people are facing so many pressures to stay afloat. Our work is mostly voluntary, so continuing to produce and document is challenging. At the same time, the lockdown has forced us to find newer ways of engaging online—video meetings have become crucial. But this definitely means that the gaps in inclusion we had before will widen, as millions aren’t able or can’t afford to participate. But even with limited internet, it’s good to know you can still be a bridge to those that don’t have access. I’m spending lockdown in my home in western Uganda—my ancestral home—with my parents and family. Radios continue to do an important job of spreading information, and community leaders are crucial, now more than ever as movements are restricted. Start where you are—that’s important.

3. Amanda Adé: “It made me realize that many people in Ireland are not aware that racism is not just an American problem.”

Wang: The first screenshot is of a video you made in which you explained, partially in response to questions from certain white friends, why Black people in Ireland have had such a strong response to George Floyd.

Amanda Adé: The video came before the Black Lives Matter protests started in Ireland. It was in response to things I’ve seen online. It was very much a hot topic, yet I saw a comment that was very dismissive of what was going on. It made me realize that many people in Ireland are not aware that racism is not just an American problem. Even in conversations with my friends, a lot of them were not sure where they stood. Some knew that racism was wrong, but didn’t feel confident enough to speak up. So the video was in response to all of that. Racism is a universal problem, and police brutality is just a symptom.

The video was made on a Friday. The following Sunday evening, I was contacted by a group of people I knew, telling me they were organizing a protest in Dublin and asking whether I wanted to speak at it. Though a lot of people seemed to get my video, I wasn’t sure how it would hold up in real life. To see people show up for the protests was a turning point. People understood the circumstances at the moment, but still made that conscious decision to come out. We had upwards of 4,000 people in Dublin that day.

Wang: You mentioned that there are similarities as well as differences between racism in the US and in Ireland. Could you talk a bit more about that?

Adé: Racism is global. But it’s also different in different places. Police brutality is a huge issue in America, but here, the police aren’t armed, for one thing. The histories of both countries are different as well. The Constitution in America was written to protect the interests of mainly the white population. It’s not like that in Ireland. Racism in America is more systemic and institutionalized. The Black community in Ireland is rapidly growing because of mass-immigration in the late 90s, but it’s only now getting to a stage where there are a lot more people of color and people from different ethnicities in the country. So we’re at the very early stages here, whereas in America there’s 400 years of history with Black people. A lot has happened in that time. Here, we need to be ahead of the game, so we don’t find ourselves in the same shoes.

Wang: On your podcast, you spoke about how you’re part of the first generation of Black people to fully grow up in Ireland. So, in a way, the generation you’re part of has this opportunity and responsibility to define how the conversation around race happens in the country.

Adé: My parents came here from Africa. For their generation, the majority of the Black people in this country were African, just now in a different place. As much as I appreciate my heritage as a South African, I’ve grown up in Ireland. My Irishness is questioned on an almost daily basis. People like me are between being African and being Irish, but not enough of either one to fully be accepted by either side. A lot of us are now defining what it means to be Black Irish for ourselves, and it’s still very new. Growing up, we were never comfortable talking about racism. It was pushed under the rug, because we were always outnumbered.

Wang: I also want to talk about how the protests have evolved since that first Monday. It was reported that the police had threatened to prosecute the protest’s organizers for violating social-distancing regulations. Large protests were canceled after that, though some small ones have continued to take place across the country.

Adé: The protest in Dublin was the first in Ireland. It was organized within 24 hours. Nobody expected 4,000 people to show up with 24-hours notice. Initially, we were marking places so people could socially distance, but it got to a point where it was a lot more than the 100 people we expected. We explained the situation to the police officers and tried our best to work with them. Everyone was also asked in advance to bring a mask and we went around with hand sanitizer. We tried to control the situation as best as we could, but it became almost impossible to keep distance. We knew that risk, and I think everyone who showed up also knew the risk. It showed me they were hungry for change.

Wang: Can you tell me about the second screenshot you selected?

Adé: I’m part of a group that started an NGO called IBO, short for Irish Black Owned. The Black community has been unable to fully integrate into Irish society. In recent years, people have been correcting that in academia, sports, and so forth, but we’re not seeing much of it in the business sector. IBO was started to help promote businesses and mentor young professionals. We’re going to run a series of workshops, raise funds to invest in businesses, and educate people on things like their credit score, how to apply for a loan, how to get a mortgage. We’re trying to change the narrative around Black people in this country and show we’re not here to take away from what it means to be Irish. We’re just trying to contribute, too.