The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated existing crises in our systems, making the work of activists more urgent than ever. At the same time, concerns about public health and the resulting changes in behavior and regulation have forced many to reimagine the way they conduct their work. In this series of interviews, Miscellaneous Files asks activists and organizers around the world to share digital artifacts on their devices for insight into how they’re navigating this time of momentous change.

The first edition of this series features interviews with organizers fighting for racial justice. Here, you’ll find my conversation with Cat Brooks, co-founder of the Anti-Police Terror Project (APTP), an Oakland-based organization that pioneered a model for community response to police brutality—one that has been replicated around North America. We spoke about APTP’s multi-front fight against state violence, as well as how Brooks’ own experience as a grassroots organizer, playwright, performer, and politician—having run for Oakland mayor in 2018—has informed that effort. I also talk to Eric Ward, executive director of the Western States Center, a hub for grassroots leaders in the Pacific Northwest and Intermountain West regions. Over decades of civil rights work, Ward has studied white nationalist movements and spent considerable time among their members. We talk about the increasing visibility of white nationalist movements in American politics, and the roots of that connection.

Along with these two US organizers, I also spoke here with Sylvana Simons, Rosebell Kugamire, and Amanda Adé, activists who work in the Netherlands, Uganda, and Ireland, respectively. Since the systems of oppression that undergird racist violence extend across national borders—despite differences in its local manifestations—the effectiveness of any anti-racist conversation depends upon the extent to which it’s shared among those working across different locales. Hopefully, this model for interconnection will remain the foundation for this special series, as we invite activists working in climate, health, labor, gender, voting rights and other specializations to join this growing exchange.

In his forthcoming Miscellaneous Files interview with Saidiya Hartman, Christian Nyampeta remarks, “Even if tomorrow is the end of the world, one ought to plant a tree.” In this moment of overlapping crises, I hope this series will help lift up and connect the voices of those doing the planting.

1. Cat Brooks: “Those preexisting health conditions are a direct result of preexisting social conditions.”

Wang: How did the Anti-Police Terror Project start?

Cat Brooks: About eleven years ago, when Oscar Grant was murdered [by an Oakland police officer], a group of us organized to bring justice to his family. We were at the forefront of that for the three years it took to get the guilty verdict. Out of that, we formed an organization called Onyx, and we worked on the many fronts where war was being waged on Black life. We were consistently in the streets protesting not only the murders that happened in Oakland, but also across the country. But the state kept killing us. Six years ago, co-founder Asantewaa Boykin said she felt like we were chasing dead Black bodies. It caused us to ask a series of questions. What were we doing? Why were we only protesting when the state kills us? What does it look like to take care of families that are impacted by state violence? And what does it look like to be not just reactionary, but to interrupt state violence before it happens and to support communities in their ability to respond?

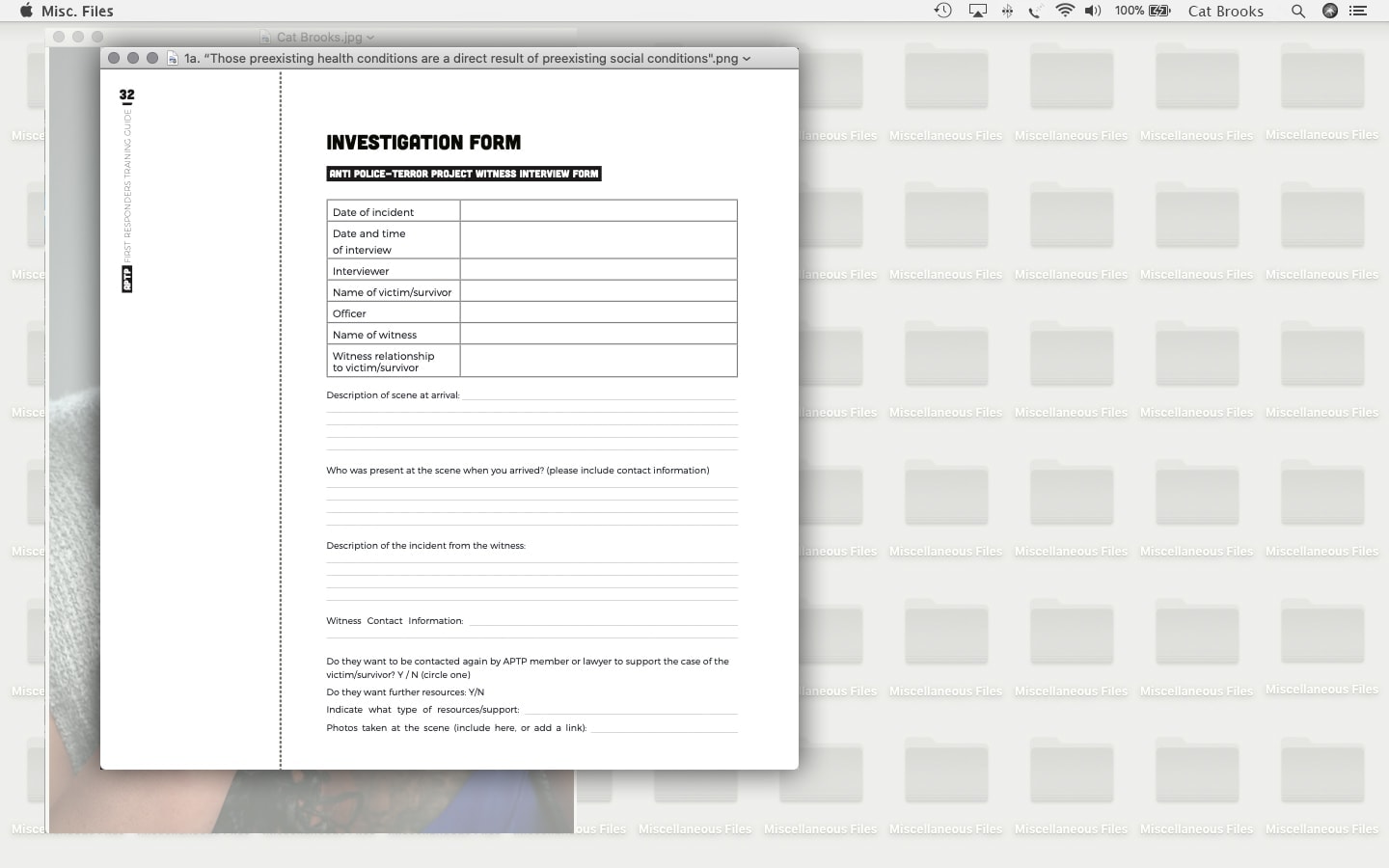

The first project that came out of this was the First Responders model, which is being replicated across the country and parts of Canada. It trains community members on how to respond: how to collect evidence, how to talk to witnesses, what their legal rights are, how to work with families, how to talk to the media, and how to protect themselves in the process. That guide exists on our website [the first screenshot features one of its pages]. Then that model turned into a full blown committee made up of lawyers, healers, psychologists, and many others who were working directly with impacted families. We have robust communications operations too, because we’re clear that we have a long way to go to impact the state and the national conversation on public safety.

Wang: The APTP is part of a group that sued the Oakland Police Department over the force it used during the current wave of Black Lives Matter protests. What led you to choose legal action?

Brooks: OPD has a horrible track record when it comes to responding to protests. They cost the city millions and millions of dollars because of all the injuries that they cause, utilizing things like flashbang grenades, tear gas, and rubber bullets. It seems that the only thing OPD understands is legal action. So the lawsuit is not necessarily about monetary compensation, but it’s about changing policies, practices, or procedures inside of the police department, and to make it unlawful for them to use the type of tactics they did in the early days of the recent protests.

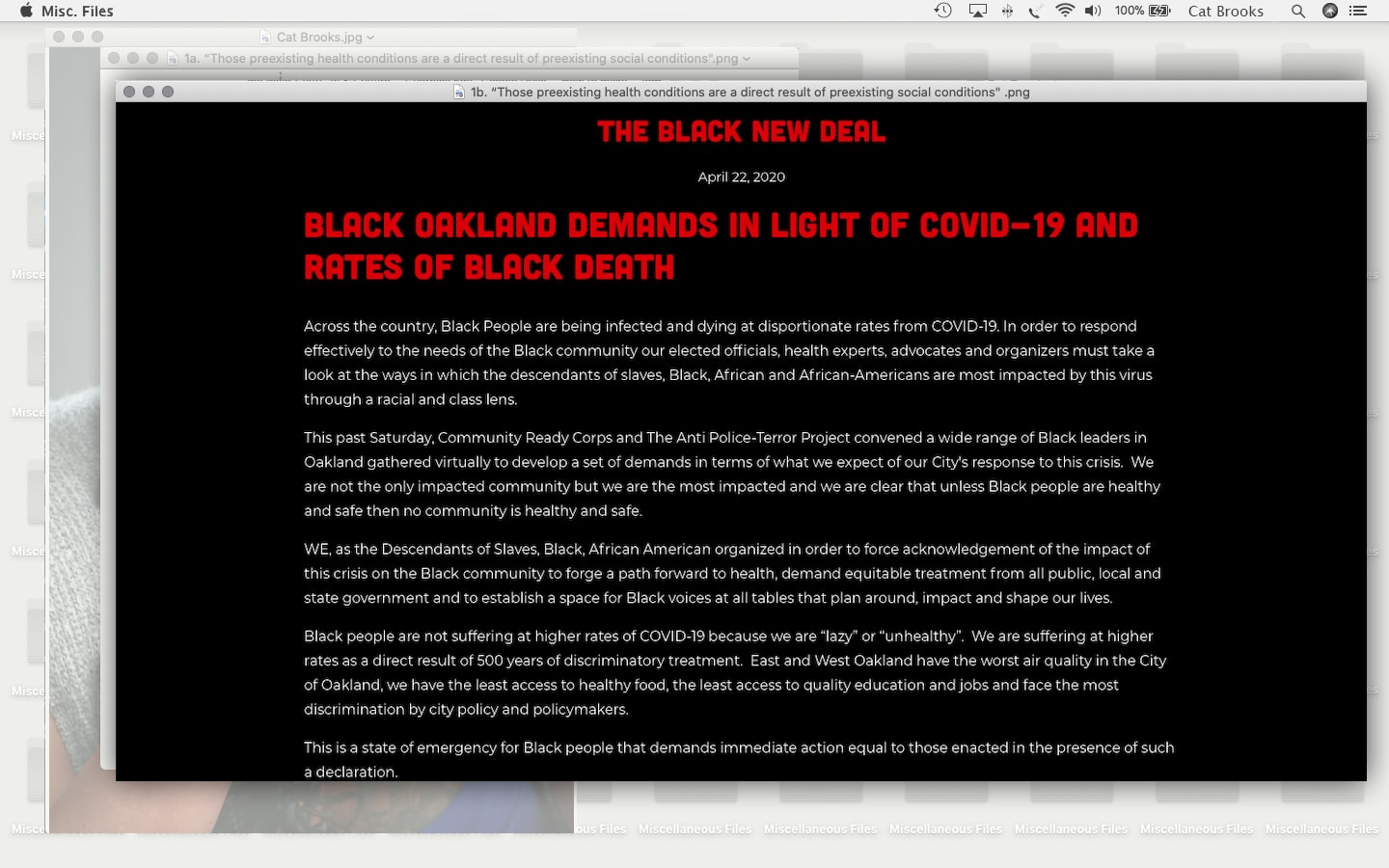

Wang: In April, APTP proposed a Black New Deal. What does that look like?

Brooks: When the coronavirus hit, it was really clear that Black people were going to be the most impacted. People have recognized that Black people have more preexisting health conditions that make the virus more lethal, but that’s where the conversation has stopped. The truth is, those preexisting health conditions are a direct result of preexisting social conditions. We have less access to healthy foods. We live in communities with the worst air pollution and we have less access to quality healthcare. All of those things create diabetes, create asthma, create the things that make COVID-19 lethal. So we saw a need for not just the immediate response—ensuring that good ambassadors to the community were getting out information and assuring widespread testing—but for ensuring that the social conditions around this moment, including longer-term demands around housing and health care, are supported. It’s like our form of reparations, if you will. It’s a call to utilize this moment to radically transform and invest in Black communities. The result of not doing that is that thousands of Black people will continue to die.

Wang: Seeing the Black New Deal makes me wonder how your experience of running for Oakland mayor in 2018 has informed your organizing now.

Brooks: I have a much deeper understanding of the way policy works, of the way our local legislature works. And because we did so well, it forced elective officials and others to treat me differently, to treat my organization differently. The fact that we were able to galvanize 43,000 first-place votes—and I’ve never run for office before—said to the state that I have the ability to build and increase a base.

Wang: The presence of Black leaders in certain regions has not curtailed police brutality, and some, particularly in the younger generation, are losing their faith in elections as an effective tool for change. As someone with experience in both grassroots organizing and electoral politics, how would you address that concern?

Brooks: One thing we have to understand is that whenever we push back, the state is going to push back harder. That’s their job, and the police are the frontline forces of that. So it’s not surprising to me that, even though there are millions in the street across the country, we continue to see state-sanctioned murder of Black bodies. We need a complete transformation of police and policing of this country if we’re ever going to end the epidemic of police violence.

Secondarily, you look at Oakland, where thousands and thousands of young people are in the streets demanding the police be defunded. And the mayor of the city has said, “I’m not going to do that. I’m going to do what I want to do because I know what’s best.” That’s not good governance. Good governance is co-governance. And unfortunately, we see so few examples of that, so folks won’t understand or believe that’s what it could be. Even the people who promise co-governance often get into office and forget who got them there.

That said, it’s the job of older organizers to help young people, to help everybody. A lot of people are disillusioned. I see a lot of Bernie supporters saying they’re not going to vote for Joe Biden. I think that’s a deadly mistake. The vote is in combination with the streets. Those two things together are the most powerful tools we have to transform the country. We can’t stop doing either. We need to be running our own candidates, truly progressive people with truly progressive track records who are truly accountable to the people. And we need to stay in the streets and put pressure on folks to do the right thing. But not everybody has to do everything. When I was running for mayor, I couldn’t go into the streets. Maybe people who don’t want to, or can’t, be in the streets will push policy or make food. Some are communications experts, and others could design plans for what a world without police actually looks like.

Wang: It’s inspiring how you work in the arts, as a performer and playwright, as well as in organizing and politics. How have those two strands developed alongside each other?

Brooks: My mom is incredibly politically active, so I grew up in a very political household. I started acting when I was eight, I got my degree in London and then moved to LA to pursue acting professionally. And then, life happened, and I ended up at an organization called Community Coalition, where I was trained as an organizer and furthered my political education. Now, all of the work I do makes some sort of social commentary.

Artists are the conscience of our society. Movements have soundtracks. In Oakland, where windows were broken, artists have created beautiful murals, political murals that reflect the reason why those windows were broken. That reflect the importance of Black life and celebrate the uprisings. And there are people who will come to my one-woman-show who will never go to a rally. And then I’ll have a hundred-or-so people in seats who are forced to think about things they might otherwise not.

Wang: What needs to be done to sustain the current momentum, especially considering the possibility that new waves of coronavirus might keep more people off the streets?

Brooks: This isn’t the beginning, this isn’t the end. Movements ebb and flow. What we’re seeing now is a continuum of a movement that’s been going on for decades. If the work that had been done in the last ten years hadn’t been done, places like Oakland and Chicago and Ferguson wouldn’t have this moment right now. It will ebb again, hopefully not before we get some of our demands met, including dismantling and defunding police departments across the country. But we’ll keep organizing and it’ll flow again. Even with the virus, we were doing car caravans, we’ve done Twitter storms, we participate in city council meetings via Zoom. And we do our best to practice social distancing and to get our organizers to model that, wearing masks and using hand sanitizer. Yes, there’s a pandemic of COVID-19, but there’s also a pandemic of police terror. For a lot of young people, they’re not worried about catching the virus, they’re worried about catching a bullet from a cop because they’re Black.

2. Eric Ward: “Our society doesn’t take the horror of white nationalism seriously.”

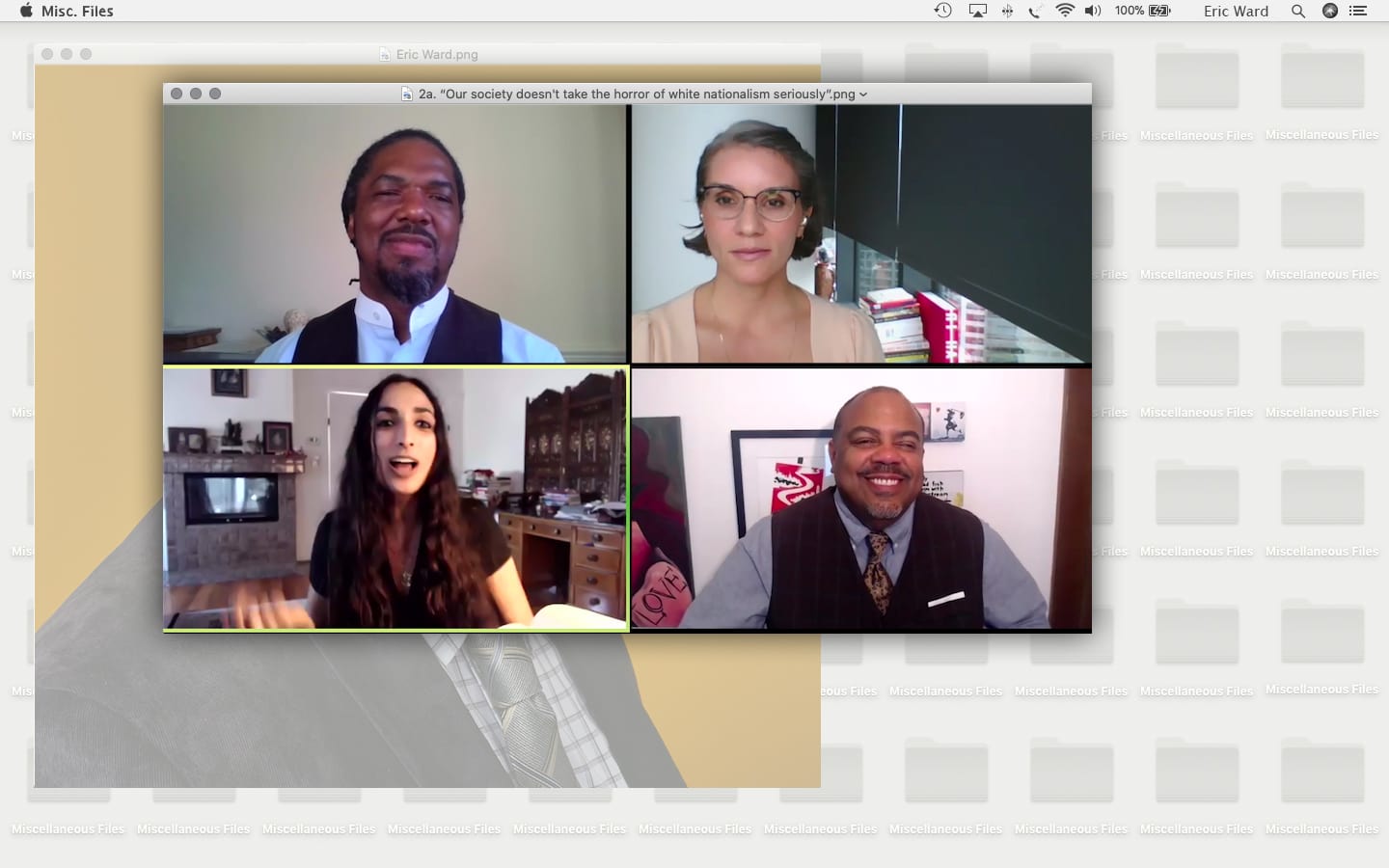

Wang: What are we seeing in these screenshots?

Eric Ward: In the first one, you’re seeing a panel at a virtual conference of nearly 200 funders exploring what it means to lead with love. This conference was planned long ago, but by the time it happened on June 3rd, it was probably one of the first funder gatherings to take place in the US after the murder of George Floyd, at least in public. We were pushing American funders and foundations to let their grantees know that they have three years of funding, so they don’t have to wonder whether they need to shrink their staff or their organization. We were also asking philanthropy to shift funding from project-specific to general operating support, which gives organizations maximum flexibility, and to double their giving for the next three years.

In the second screenshot, you see national social justice leaders from around the US participating in a workshop we, the Western States Center, hosted about the spread of conspiracy theories in the country. We started with a look at an old anti-semitic conspiracy called The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, a forgery from the 1900s that tends to be foundational for a set of conspiracies popularized today.

Wang: You’ve moved through various levels of institutionalization in your career, starting as a community organizer and then landing in top positions at the Ford Foundation and Western States Center. What kind of roles do different kinds of institutions play in a moment like this?

Ward: When I was young, I made up a theory that there are two types of organizers: the scientist and the artist.The scientist looks at the rules of organizing, the probabilities, the case studies, and builds their organizing on calculations. Then there’s the artist, where I would put myself. I’m too lazy to do all that calculation, so I tend to look for feelings and narratives. That’s driven me to be less focused on the institution and more on my skills. I do believe that people are at the heart of organizing, so while I cherish institutions, I think they are vehicles for change, not change itself. But if our role is about helping people find their voices, that means being willing to switch positions at different times, depending on what people need.

Wang: You’ve studied many white nationalist and white supremacist groups, and you’ve spent considerable time among them, too. I read a Vice article about how some of these groups were present at the Black Lives Matter protests. One of them was described as the largest militia in the US, with no further explanation. I was shocked that the journalist wrote that down so matter-of-factly.

Ward: White supremacy is a historic and present-day system of discrimination and racial disparity, while white nationalism is a social movement that actually—and this might be hard to understand—wants to overthrow the system of white supremacy. It wants to replace it with a system that promotes ethnic cleansing to create a white-only ethno-state. So in short, if white supremacy is about systems of exploitation, white nationalism is about racial cleansing.

The white nationalist movement in the US really came of age in the post-civil rights movement. It has always had a violent streak, but in the last six years, it has begun to mainstream itself, attracting folks who didn’t see themselves as white nationalist. And it was able to insert itself into a broader politically right-leaning coalition. Over the last four years, starting first with an unarmed paramilitary organization called the Proud Boys, they were able to promote violence on the streets of America. But the Proud Boys faded and a paramilitary formation known as the Bugaloo Boys began to rise. Unlike the Proud Boys, they are armed, and they are likely one of the largest white paramilitary organizations in the US. Not everyone in it is white nationalist, but white nationalists drive and influence the group. It has shown up and inserted itself in recent civil rights protests in a lot of different ways, first claiming to be there in support, then making clear that they were trying to incite violence in hopes of setting off a race war.

Wang: Thank you for clarifying that distinction. During that meeting, what strategies did you discuss to respond to the rise of such white nationalist groups?

Ward: Sadly, we live in a society where white supremacy and white nationalism play off one another. So one of the challenges is that our society, as you noted earlier, doesn’t take the horror of white nationalism seriously. It can mention it as a curiosity and gloss right over it, as if it’s not a real issue. We need to get the public and elected officials to take it seriously. The white nationalist movement’s success is because of the lack of response from mainstream America and mainstream public institutions.

Protests have to go on, despite the fear of abuse by law enforcement, despite the threatened violence of white nationalists.There was an incident in Seattle where an individual drove his car into the protest, hopped out, walked into the crowd with his gun, and shot a protester. This is not Selma, Alabama. This is Seattle, Washington. We receive reports of incidents like this nearly every day now. It’s time for civil society, NGOs, and other countries to send observers to the US. We need them to document the violence against protesters and African Americans. And we need those who support human rights outside the US to march, mobilize, and petition their governments to intervene, since the US government has shown itself ill-equipped to respond to the violence being thrown at protesters and African-Americans.

And we need a US media that talks about white nationalism as a real political threat. White nationalists have murdered more Americans than any other racial or religious political group has; they’re responsible for the murders of over 200 Americans in just the last four years. This is happening nearly every day in the US, but the media doesn’t act like it.

Wang: Many are discussing how to translate the momentum of the current protests into something more concrete. What kind of strategies would you recommend?

Ward: First, I should say that a lot of our strategies aren’t shared publicly because we’re focused on keeping people safe. But there are some I can share. One, there’s a list of policy demands on the website of the Movement for Black Lives. If the US media would spend at least a third of the time they spend reporting on people breaking windows on what folks are actually saying at the protest, these demands would be more known to the American public. Our media is choosing not to give any airtime to reasonable demands that benefit not only the Black community, but everyone.

Secondly, if you are inside the US, demand that your mayor act in support of the rights and safety of all citizens, including those protesting. And if you’re outside the US, protest outside of the US consulate and ask the equivalent of your secretary of state.

Thirdly, know that many white nationalists in the US are operating on internet infrastructure outside the country. They are able to communicate and coordinate because of servers that exist outside. One thing folks outside the US could do right now is to put pressure on tech companies to cut off those communications. Make white nationalists build their own platforms. This is not a denial of free speech. It is denying the ability to engage in violence targeting minorities.