Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

A Twitter sage and a comforting voice of the digital age, reliably funnier, more incisive, and better able to deliver near-perfect commentary on both the quotidian and the serious than perhaps anyone else on the platform, Patricia Lockwood is a rare gem of joy—offering chaotic good in an online world that typically leans toward chaotic evil.

Following two books of poetry, Balloon Pop Outlaw Black and Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, Lockwood’s 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy, was an immediate hit. In it, she took the open, wry, and self-deprecating humor she’s known for on Twitter and directed it at her own family, considering them through the lens of the internet—where anything can be a joke if you frame it right. Her essays for the London Review of Books frequently invoke her online life, and it was there that she dropped an essay about what it’s really like to live online (it was later presented as a Powerpoint lecture at the British Museum). That essay felt like a crystallization of the Lockwoodian view of the world, pointing out the patent absurdity of our moment and the way we process it. This essay would become the basis for her much-awaited first novel, No One Is Talking About This.

“I’ve always been able to tell, going back to 2011, what belonged in my notebook versus what belonged online,” she told me over a Zoom chat in early February. “[These are] observations that almost feel like they fit in the portal but actually don’t, are standing outside it or weren’t quite okay to say in there.” The portal is a term the novel’s narrator, and Lockwood herself, uses as a stand-in for both “a micro-blogging site like Twitter but that I’m not going to say is Twitter” and for the internet as a whole. It’s an apt metaphor; we use the phrase “sucked in” to refer to accidental time wasted on apps, and being totally immersed in something online can feel like stepping through a screen and into another world. In the novel, Lockwood’s narrator has become mildly famous for being funny online and essentially lives in the portal. Through her, we see just how much of our lived reality is fabricated through what happens on screens.

Reading No One Is Talking About This is a pleasurable experience thanks, in part, to the specific kind of serotonin jolt that comes when you recognize a reference or old joke—which will happen frequently if your online life intersects with certain literary or media-centric spheres, or if you’re tapped into meme culture. You are in on this book; “it me.” It is also a heart-wrenching read; halfway through the novel, the narrator’s pregnant sister discovers her baby has a rare disease that all but ensures she won’t live past infancy. This forces the narrator to confront the stream of reality as it comes, away from the screen. (That events like these are based on the experiences of Lockwood’s own family makes them all the more painful.)

The novel tries to reconcile a life online with one whose problems cannot neatly fit into the portal. Private though they may be, the narrator has an impulse to share them anyway—because if she doesn’t, are they real? These are questions we now confront daily: How much of ourselves to share, how much to make of what we do share, how vulnerable to be. Here, Lockwood gives us a timely portrait of modern life online—underscoring the relentless tensions between laughing and crying, sharing and withholding, the internet self and the corporeal one.

1. “ I just experienced something quite real: The full force of ignorance in my own assumptions.“

Mickie Meinhardt: Some of these files are older memes, some of them very old, and seeing them is like a hit—a hit of old internet that feels so good.

Patricia Lockwood: It feels so good. It’s magical. But you forget that all of this is very tied to time. It’s time-stamped, really. You can find out the exact day when everyone was talking about something and it was spreading like wildfire. The interesting ones are those with repeat cycles, multiple days when they consumed the world. They don’t necessarily carry you back to that day but almost to who you were at that time. You don’t remember the specific, concrete details of encountering this thing; it’s a slipstream, like everything is coated in Vaseline. But you can return to the person you were at that time.

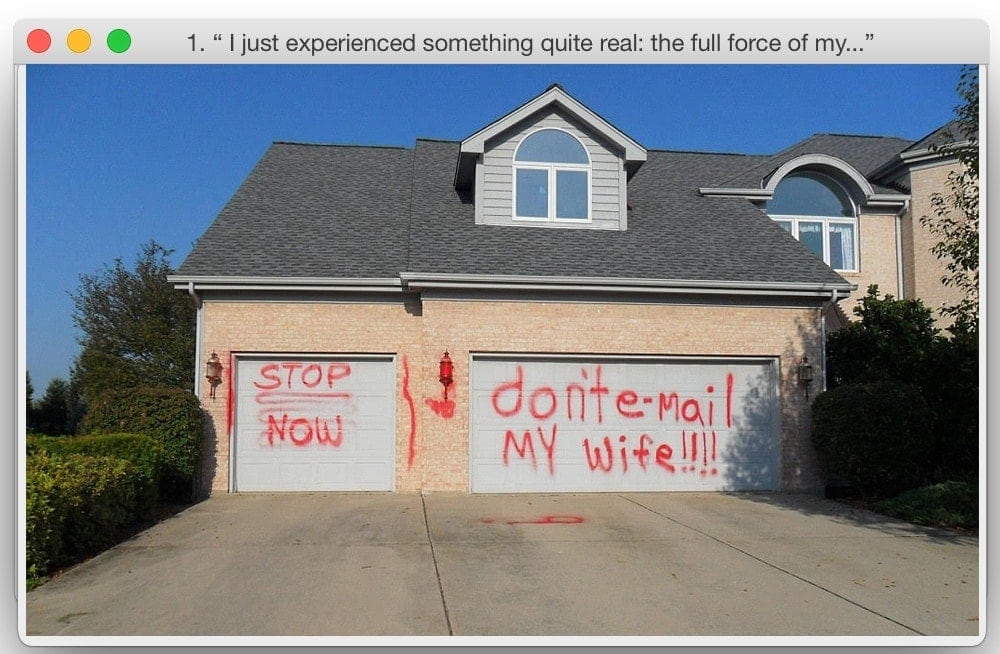

Meinhardt: This is in the second paragraph of the book, found in a list of things the narrator encounters instantly when logging onto the portal: “Close-ups of nail art, a pebble from outer space, a tarantula’s compound eyes, a storm like canned peaches on the surface of Jupiter, Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters, a chihuahua perched on a man’s erection, a garage door spray-painted with the words STOP! DON’T EMAIL MY WIFE!” Why did it make it in so early?

Lockwood: It just says everything. You’re looking at the text first, but then you start to look at the house. What is going on with the design? A portion of the internet is looking at these awful modern houses that are just cobbled-together, style-wise. Who is living in these places? What is that, a window above the garage? And then you’re imagining this story where this guy really does not want a neighbor—we’re assuming it’s a neighbor—to be emailing his wife. Where do we think this is? It’s an every-house. There is no man, there is no wife. One of the outer light fixtures is painted completely blood red.

Meinhardt: And it’s on the driveway.

Lockwood: That raises another question: Did another person spray-paint this on the house of the guy whose wife he was emailing? I had always assumed that the man who lived here spray-painted his own home, but now I don’t think that’s accurate! It’s gotta be completely backwards.

Meinhardt: I always thought the person who spray-painted it was a little drunk because of the squiggles, like he’s testing it. But wouldn’t you do that on a piece of newspaper if it was your house?

Lockwood: True, and the people who live in these houses are really protective of their driveways. So I’ve been looking at this completely backwards for years. Oh this guy spray-painted his own garage to tell someone in the neighborhood not to email his wife. Wow. I just experienced something quite real: The full force of ignorance in my own assumptions.

2. “There’s a grabbable element to the things I put in.”

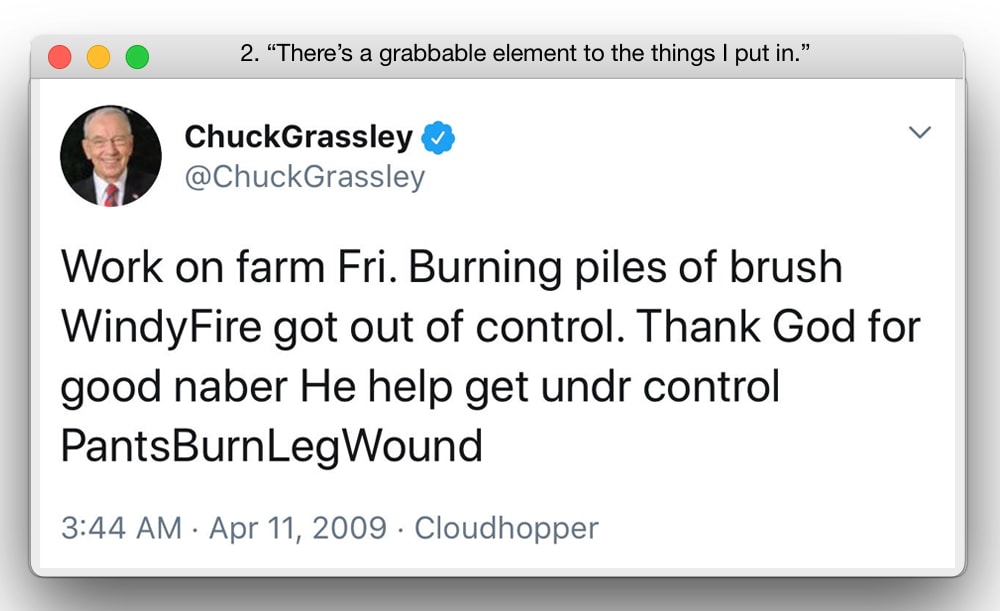

Meinhardt: This is an old tweet! It is an example of the absurdism that results from older people using technology they don’t fully understand.

Lockwood: On January 6th [during the 2021 Capitol insurrection], this guy was pretty close to being tapped in the line of succession! It’s something you never want to think about. This tweet became relevant again; I was once again thinking about Chuck Grassley. It’s from 2009? Why was that bitch on Twitter so early? Early fucking adopter. There’s something eternal about Chuck Grassley, that’s what I’m going to say for the record. He’s one of those images that cycle back; Chuck Grassley has an eternal cycle of relevance, and why is that true? Maybe we should let him be the president. I don’t think that. But what if we did?

Meinhardt: You say in the book that not long from now, hardly anyone will recognize “PantsBurnLegWound.” To quote: “Her most secret pleasures were sentences that only half a percent of people on earth would understand, and that no one would be able to decipher at all in ten years: grisly british witch pits, sex in the moon next summer, what is binch, what is to be corn cobbed, that’s the cost of my vegan lunch, pants burn leg wound.” But I don’t think that’s true. The internet has memory, as demonstrated by retweets and renewed jokes.

Lockwood: Now that we’re talking about it—it’s going to be in some new Bible. It’s been 12 years and we know more about it today than we did then. That’s saying something. I’m getting very wise.

Meinhardt: Don’t you think that idea is true of the entire internet though? That we might not be able to decipher anything from ten years back?

Lockwood: It’s a little of both. Because if you’re writing a book about it, that means you’re producing a document that people can pore over and dissect, and trace back.

Meinhardt: Was that an intent of yours with this book—to document the internet and keep it around for posterity?

Lockwood: More than that: to make it permanent. You do feel it slipping through your fingers; I guess that’s the experience of time. Part of it was wanting to pin it down, and I guess it’s appropriate that I wrote it with my index finger, just poke poke poke, seeing what I can make permanent. Some of the people who have interviewed me are older and don’t know about many of these things, and they ask how I chose what I put in. It has to be something that pertains to that fleeting sense of time, but it also has to stand on its own. Like people writing op-eds about the fancy ham; we remember that day, we remember that op-ed, the little journalistic photo and byline, but I think people in the future can also imagine what it’s like to read a piece in the newspaper about a fancy ham. There’s a grabbable element to the things I put in—people could, from some future vantage point, imagine it.

3. “All literature is the translation of an encounter.”

Lockwood: I had to cut this from the book, but I’ll read it to you:

“A former presidential candidate, whose face was as long as a cartoon shoe, had favorited porn in the night. It was always thrilling when this happened. First there was the porn itself to dissect—in this one, a red-blooded American housewife stumbles upon her stepdaughter getting fucked from behind by her boyfriend, who seemed likely to shoot an unbelievable load of mayonnaise into her at the end. Twist, though: the woman in the clip, who stood in a hallway theatrically pleasuring herself while her stepdaughter was rogered, looked exactly like the candidates’s wife. This was somehow thrilling too, in its innocence. He would always desire her, or at least the blond substance that flowed through her eternal sketch. She thought, then, of the woman as separated twins, of the divergence in use between their identical beauty—how had one ended up in a porn clip disseminated by Sexuall Posts, and how had the other become the wife of a man who was outspoken in his belief that people should not manipulate their genitals?”

So that was the Ted Cruz line. He didn’t make it in because it’s one of those things you can’t quite follow along with if you weren’t there.

That doesn’t mean I don’t think about it all the time though. One of my earliest popular tweets was about Rick Perry. Rick Perry has legs, he keeps coming back, and every time he does, that very early proto-Tweet gets retweeted a bunch. Ted Cruz is like that.

Meinhardt: What was the very old tweet?

Lockwood: That’s for real Tricia Lockwood-heads only. But every time Rick Perry does something dumb, it will be retweeted. Like how every time Ted Cruz incites a riot at the Capitol, we all have to think about that time he favorited porn in the night!

Meinhardt: How, as a writer, did you translate fragments of your internet world, like the Ted Cruz example, into a work of literature? How did you make sure people would understand your references when the visual, almost experiential context of partaking in something online was removed?

Lockwood: All literature is the translation of an encounter. It doesn’t seem that different to be translating your encounter with the Ted Cruz porn tweet than it does to be translating your encounter with a croissant breakfast in Paris after your balls have been shot off in the war. You are talking about eating something, drinking something, opening the newspaper, watching people pass. You are choosing either a fine or a coarse grain of description. It seems unimaginative to think people won’t be able to relate to these vignettes because they describe mental processes or intangible encounters or because they are highly specific to their moment. The nouns and verbs are still there. A reader may not be familiar with the ham op-ed, but she still knows what ham is; she meets it on that plane.

4. “But that’s how these sites work!”

Meinhardt: Your narrator’s father was a cop. One chapter opens with this line: “Every fiber in her being strained. She was trying to hate the police.”

Lockwood: I like the things that people on the internet can’t talk about. At this point in time, if your dad is a cop, you’re probably not talking about it. It’s like being rich; you’re trying to keep it in the background. I don’t try to keep my dad in the background because he’s much weirder than a cop. He’s a Catholic priest, and that’s something you have to talk about because it’s so absurd. But he was always a cop lover. He worships blue-collar workers and was a police chaplain; he had this reflective thing in the back window of his car that said “Police Chaplain,” and we didn’t figure out until we were adults that he was doing it so he wouldn’t get tickets. I’m not going to have the protagonist’s father be a married Catholic priest—that hews a little close—but this felt parallel. I’m interested in that moment, like how everyone says [the musician] Mitski’s father is CIA. You have to leave certain things in the background because a lot of times they don’t necessarily have anything to do with you or your ideological positions; you’re factually ashamed of those things, and you definitely don’t talk about them online.

Meinhardt: I wonder if there’s going to be a point where those conversations become more normalized; where we can say, “This is my family and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Lockwood: My brother was in the Marines, and in the early days of Twitter I think he was on his final tour. I did tweet about him coming back home, which I probably wouldn’t do now. In the really early years, it felt like everyone who followed you was your friend. More than 800 followers, and you don’t have that feeling anymore. The bulk of responses are from people you don’t know.

Once you leave a platform, you’re able to see how you were behaving weirdly on it. I think people recently had that with Tumblr; they got away from it and looked around and were like: …Oh. But that’s how these sites work! They create their own culture.

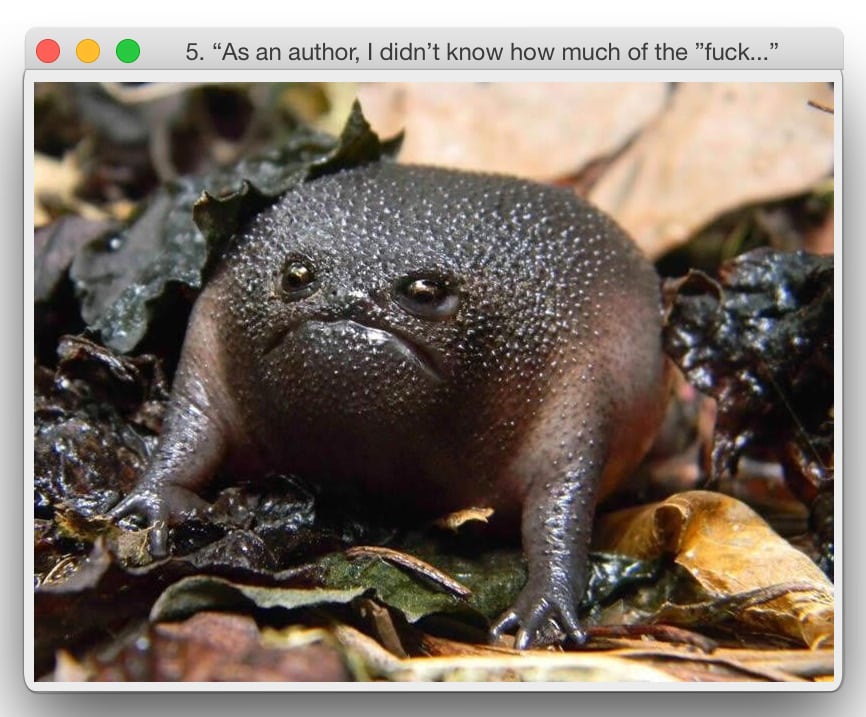

5. “As an author, I didn’t know how much of the ‘fuck you’ I wanted to put in.”

Lockwood: Oh, he’s so beautiful. And he could have been one of a hundred frogs. He could have been the melted-cheese blob fish. But I really like his little face, and that’s really how I was feeling in January, probably because of the insurrection. When I see an animal like that in the portal, I feel like I reach out and put it in this little space where my own heart is. I give myself a transplant. I think that’s why we say “it me.”

As opposed to an “Abortion, who will be the next police officer?” I didn’t put as many things like this in the book. I was retaining an air that’s slightly more positive. I did put in the protagonist’s feelings of being trapped or smothered under images, and some things about the auto-playing videos and the brutality we see. But there was a lot more that I cut out. I recognized I wasn’t really commenting on them, I was just like, “Here, fuck you.” And as an author, I didn’t know how much of the “fuck you” I wanted to put in. Maybe a little.

6. “When the internet is good, it’s like going down a long waterslide in the best bathing suit you ever had.”

Lockwood: This is the emergence of the internet into the real world. As soon as you were able to take a picture of yourself on your phone—perhaps in a Burlington Coat Factory, where you encounter a Garfield onesie or a Halloween costume, or whatever—you have no choice but to put it on, zip it up, and take a picture of yourself. And once you have that picture, you’re going to put it online. It’s like “if you give a mouse a cookie…” That’s where you start tailoring reality to the portal; you’re directing your actions to be consumed by it. Such as with the riot at the Capitol, which was intended to be consumed online.

Meinhardt: When did you decide to work in the story of your sister and family?

Lockwood: As soon as it started happening. It pretty much took up all of my attention; the beam of my sight was trained in one way, on this manger-like scene, an archetype almost, that had my full attention. You’re not thinking about what’s trending or who we’re supposed to hate that day, you’re thinking more about the language that we use online and how we’re reflecting our experience there, or how we’re filtering our experience through that.

Meinhardt: Did you feel that same shift the character experiences: “I’ve been living in the portal and now I’m in between”?

Lockwood: Oh yeah. I’m not “exploring that in fiction,” that was very real. Obviously, I’m someone who’s very comfortable living on the internet, without a body. When the internet is good, it’s like going down a long waterslide in the best bathing suit you ever had, right? I like to be there, I like to live there, but your body is required to do other things when something like this happens. You have to stand up, put on real clothes, walk into a hospital. Be an adult, I guess, or in more ironic parlance, “a real person.”

Meinhardt: Be Very Offline.

Lockwood: Extremely Offline. But there’s something extremely tactile about the internet; you are experiencing it through your finger, this point of contact. But you also experience a child that way, held right here between the eyes and hands and arms. So that part didn’t feel that different.

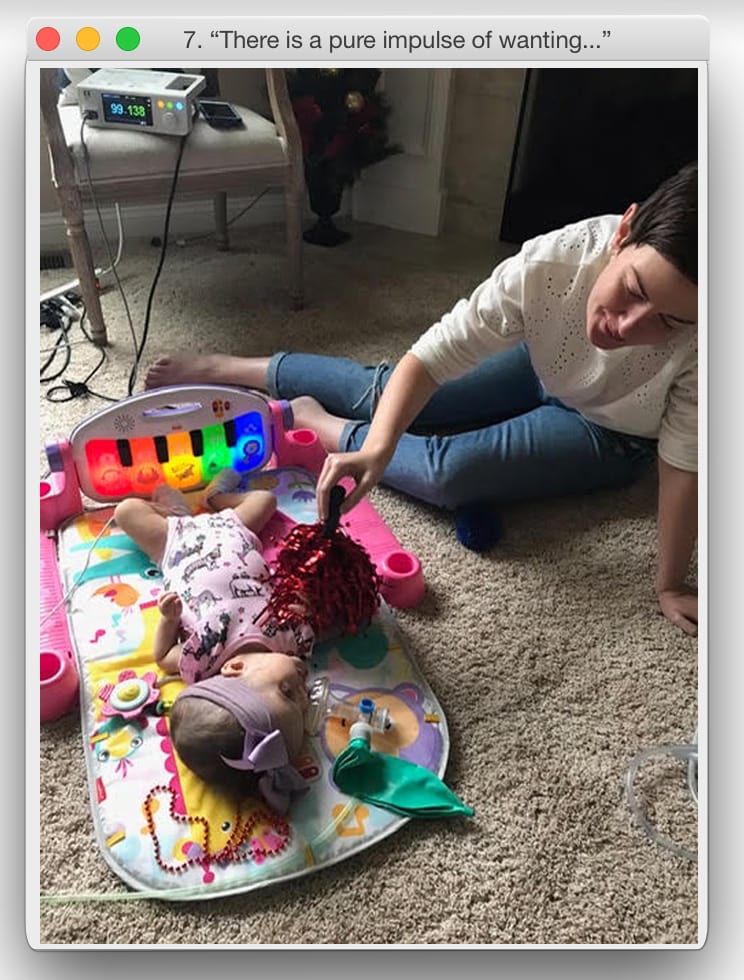

7.“There is a pure impulse in wanting to put things into the portal.”

Lockwood: That’s my sweet niece, her foot piano and her pompom.

You tell yourself at the beginning of an interview cycle that you’re going to preserve the boundaries between the fiction and the true, and protect the material that’s from your life, but I’m not that kind of person at all. For a person to be remembered, you want to put an actual face to them. It’s a human impulse, but it’s also just nice.

In the second part of the novel, the protagonist says she would be happy for people to encounter the baby in the broad stream of things, as just one person among others, among everyone. There is a pure impulse in wanting to put things into the portal, like ourselves in Garfield costumes, our niece, our children, the people we take care of. And the impulse can expand to fill the entire world. Something that feels small and even petty can become enormous.

Meinhardt: We do spend so much of our time online, putting things out there, trying to be funny or sound smart. It can be nice to put something up and say, “I have a big serious life thing on the other side of the screen, too.” My mom passed away last year, and I posted photos of her every so often as a reminder: She lived, this happened. Immortalizing your niece, or something like that, is human.

Lockwood: It’s not just about choosing what you put in the portal, but the size of what you present. You can make things small or big. When you post a picture of your mom, or when I post a picture of my niece, that’s something very, very big. And you want people to experience it as something big—as a part of real life.

Watch a recording of Mickie Meinhardt and Patricia Lockwood in conversation with Lauren Oyler (Fake Accounts) discuss new books, writing the online life into novel form, and all the trappings of being labeled an “Internet writer.