Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

I first read Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, a book about a young woman who decides to sleep for a year, when I couldn’t see how I would survive the year awake. I did ridiculous things and cried about the ridiculous things I did, but that’s not how an Ottessa Moshfegh story would proceed. In her short fiction and novels, a character might sustain their prescription pill-induced hibernation by turning it into performance art (My Year), or understand that the only way to escape her world is by finding the right person to kill (“A Better Place,” from the collection Homesick for Another World). Ottessa Moshfegh might follow an elementary instruction manual, like Alan Watt’s The 90-Day Novel, and grow it into something much stranger, much more beautiful, and much more unsettling—something that would go on to be nominated for the Man Booker Prize (Eileen). (Also Ottessa Moshfegh: telling a shrewd interviewer about how she initially shaped the novel according to Watt’s manual, and then realizing that the resulting interview most probably compelled the Booker jury to grant the award to someone else.)

Over two Skype sessions, I talked to Moshfegh, the child of Croatian and Iranian classical musicians, about how Nirvana opened her eyes to the “freedom to be ugly,” how to draw the line between sensitivity and sentimentality, and a range of cultural fragments that have shaped her work.

1.“There was this dirty loveliness to the way it captured the people”

Mary Wang: Can you identify a specific process in your work?

Ottessa Moshfegh: Yes, I can. I’m an early riser, and I generate work mostly in the mornings. I’ll work until lunch, and whatever happens after is bonus. After noon or one o’clock, my brain can’t, shouldn’t, or doesn’t want to create anymore. I haven’t gotten adulterated by the world yet in the morning, and I feel that I’m in a private space with my draft. I can do things without too much premeditation or risk—I need to feel like I have room to be wrong. In this blurry place, I can do an easy version of a huge plot twist or work on a part that feels ominous and difficult and tell myself it’s a filler. I’ll then look at it, and I’ll write into it and clarify it. I like being regimented in the morning. I eat the same thing for breakfast every day—toast with almond butter and jam—and it’s my way to settle into a private space with my book.

Mary Wang: How do you know something is worth pursuing?

Ottessa Moshfegh: It’s usually when a character immediately feels like a person I have a relationship with, and I can identify the weirdness of the rapport as something that’s familiar to me. It’s not that I like them, but I do feel I’m in a special position to observe them and love them. I don’t ever remember loving my character in My Year, but I had great sympathy for her, as well as the distance required to write something that was heartfelt and somewhat satirical. Those are the characters I love the most, when I can be part of them and impose myself in them, and we can grow together as a conjoined twin.

McGlue [from the novel McGlue] wasn’t a character in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, but when I was writing him, I could see him walking through a scene in that movie. It takes place in roughly the same era as McGlue, and it’s about a character called William Blake, played by Johnny Depp, who goes West by railroad and takes a job in this town called Machine. He sleeps with a prostitute, her lover comes back and finds them, and he gets shot. Blake then meets this Native American man, played by Gary Farmer, with whom he roams through the woods while this posse of men are hunting them. There’s this hauntedness about the movie, because you could read it as if Blake’s already dead, and he’s entering this mystical realm. It’s visually beautiful, and there’s this delicate grit to the world, which is violent, hostile, unfair, but also full of nature, magic, and wonder. It was a visual cue for how to imagine this story set in a past I don’t know. I loved the closeness of the camera and the naiveté of the characters. They were archetypes but they were also individuals. There was this dirty loveliness to the way it captured the people.

Mary Wang: “Dirty loveliness” is an apt description for what a lot of your characters display. As a reader, you witness bodily movements that are rarely recounted in works of fiction. You see the characters puke, poop, and inspect other characters’ anuses. It’s not presented as an extraordinary act; it’s just how close the reader stands.

Ottessa Moshfegh: I think they’re vulnerable people pretending to be not vulnerable. Showing you their bodies like that is their way of saying, “I’m so un-self-conscious, I’ll show you the inside of my vagina.” Making the reader feel disgusted is a way for the characters to be tough—or to pretend to be.

2. “There’s a line in my writing between sensitivity and sentimentality”

Mary Wang: You’ve spoken about how, in this video of Lena Zavaroni’s performance of “Going Nowhere,” you can look inside her mouth and you can see the mouth of a child. Reading about her history as a child star, her battles with anorexia and depression, and her tragic early death, I imagined someone quite fragile. But when I watched the video, I saw someone strong and powerful. She projects her voice into the audience and tells them to look inside her mouth.

Ottessa Moshfegh: She really lays herself bare in that performance. I wish I could write a character like that, but I wouldn’t believe it if I made it up. There’s a line in my writing between sensitivity and sentimentality. Sentimentality is a curse, and it turns any art into trite entertainment. In My Year, that’s exactly what Reva, the protagonist’s friend, does. She very rarely expresses sincere vulnerability and instead presents a canned version that keeps her at a distance from the protagonist. It’s a way of saying, “I’m perfect and I totally know everything, even my flaws and weaknesses.” I relate to that a lot, but there was a point at which it became so ridiculous that it became comedy. The same thing as with the protagonist’s disillusionment with the world—I can totally relate to that, but in order for this to be more than me writing in my journal, I need to create a fictional scenario and push the character past what’s familiar and into the absurd.

Mary Wang: You’ve said writing saved your life. Is sadness productive?

Ottessa Moshfegh: No. In order to write well, I need to have the ability to be honest with myself without it causing pain. When I’m really sad, honesty hurts, and I find myself not going to interesting places in my work. I guess you can be sad and strong at the same time. Writing requires strength, discipline, and a tolerance for loneliness. The longer I have a partner, the more loneliness I want, because I’ve lost it. But loneliness is also excruciating unless I’m writing. Yet you can only write so many hours in a day, and it takes a lot of effort to fill the void of not writing.

3.“There’s a universal experience of sadness”

Mary Wang: There are all these ways in which we can explore the sadness of the protagonist in My Year of Rest and Relaxation. We learn that both her parents have passed away, and that she feels detached from the world around her. At the same time, her sadness also seems placeless. Sometimes, sadness just is.

Ottessa Moshfegh: There’s a universal experience of sadness. We’ve always struggled to explain human emotions. There was a time when people in the Western world thought depression was something you caught. Then psychology became a science and suddenly we see ourselves as having psychologies. But there’s a general sadness that’s part of the human experience. We can call it sadness, but it existed before we even had a word for it. What’s the thing we feel when we contemplate death? When we grieve for someone we love? Is that really sadness? That would be a pretty simple way of saying it. Her sadness is like my sadness, and, I hope, your sadness. It’s not that someone can say the right thing and it can go away. It’s the thing that defines who we are as individuals.

Mary Wang: If “sadness” is an insufficient word, it’s also because there’s a drive in our society to cure or eliminate it. When I’m feeling sad, there are people around me who want to make it go away. Is there another word you think is more suitable?

Ottessa Moshfegh: No. Maybe in another language, but I don’t know it. Thinking abstractly about depression is so easy, but the experience of it is more like being in touch with something very, very deep that is a necessary part of the human experience. It keeps us grounded in our mortality. Depression is an intolerance to life, but it can also be profound. Maybe the trouble is that we don’t respect it enough. What if you’re actually having the most important experience of your life? I probably learned a lot more about myself, life, and God from being depressed than from anything else. Being in love is maybe a close second.

Mary Wang: Why did you set My Year in the year 2000?

Ottessa Moshfegh: I didn’t realize I had set it then until it became apparent that I was describing a New York pre-9/11, when there was still a sense of optimism. It was the end of a New York I really loved, when it felt mysterious, creative, and full of history. The more practical reason was that if I’d set the story now, the character’s decision to go into hibernation would be a very obvious response to what’s happening in her environment politically and socially.

Mary Wang: Is there still space for a person to self-marginalize in the gentrified New York of today, even with wealth, intelligence, and beauty on their side?

Ottessa Moshfegh: I think you can convince yourself of anything. We’re not as susceptible to culture as we think. There are people who hide in their homes; we just usually think of them as unsightly.

Mary Wang: Speaking of ugliness, you established the protagonist in My Year as someone who was physically the opposite of Eileen [the protagonist from the novel Eileen]. Eileen is unremarkable, and she doesn’t see herself as beautiful, while the protagonist in My Year is hyperaware of her looks.

Ottessa Moshfegh: I asked myself, What if she’s the opposite of Eileen and some of my other characters? So much was made of Eileen being this disgusting character—no way I was going to write another character that was so unsavory and have her sleep all day! I had this friend in college who said, “Of course people on TV are good-looking, because I want to look at good-looking people.” I felt the opposite. I found it boring that everyone had to be beautiful in the same way. At that age, beauty represented conformity for me. But after she told me that, something clicked. So when I started writing this book, I realized I had to give the reader something to fulfill a biological need to tolerate this character. If she was going to put the reader through all this shit, she had to look like Cindy Crawford.

4.“Its willingness to be ugly in order to be itself”

Mary Wang: You’ve said that grunge was the only cultural movement in the US you’ve identified with.

Ottessa Moshfegh: It was really important to me when I was an adolescent. It’s the time people start individuating, but there’s also a ton of conformity. For me, the option of conforming was so unappealing. Where I grew up, you had to be pretty, fun, and play soccer. Ugh. I didn’t care about fitting into that. I was raised as a classical musician and I had a great sensitivity toward music, but I had never identified with any pop music. It was 1992 when Nirvana first played on Saturday Night Live. I was eleven or something, and it completely blew me away. The feeling of that band and its reverence for its own irreverence felt divine to me, in its freedom and its willingness to be ugly in order to be itself. It was so liberating and at once terrifying. It planted a seed, as if that gave me permission to not give a shit about what conformists are doing and just pursue my art.

I have complicated feelings about Kurt Cobain, but he made a huge impression on me. I remember him saying in a documentary, probably after he’d reached a point of irritation with the interviewer, “I don’t think most people really love music.” He was talking about the shit that’s on the radio, and I was like, Yeah, exactly! He really does. He’s willing to deal with all this bullshit and still be an artist. I appreciate him saying that so much. To really love music is not to love listening to it—that’s easy. But you can tell he loved it the way Bach loved it. It was spiritual and it was his entire life. We rarely see people like that in the mainstream, and grunge was the rare occasion when something underground and profound hit the TV. We were really lucky for that.

Mary Wang: The freedom to be ugly describes your work pretty well, too. I think that all the best work has this sense of freedom, where someone, at some point, decided, “Fuck it. I’m just going to do this thing, and it’s most probably wrong, but I don’t care.” The loyalty is to this thing you’re making instead of whatever the consequences are. Was that when you realized that writing could save your life?

Ottessa Moshfegh: It was very soon after. I knew I had an unwieldy amount of “passion”—for lack of a better word—but I didn’t exactly know how it was going to become a practice rather than a monster. If you don’t foster it, it can become destructive rather than creative. In that sense, I feel that writing saved my life—if I had never found writing, I might have been dead. I’m not saying I would’ve shot myself with a shotgun, but I don’t think this person would have survived.

5. “I’m not going to spend more time feeling in opposition”

Mary Wang: What are you working on now?

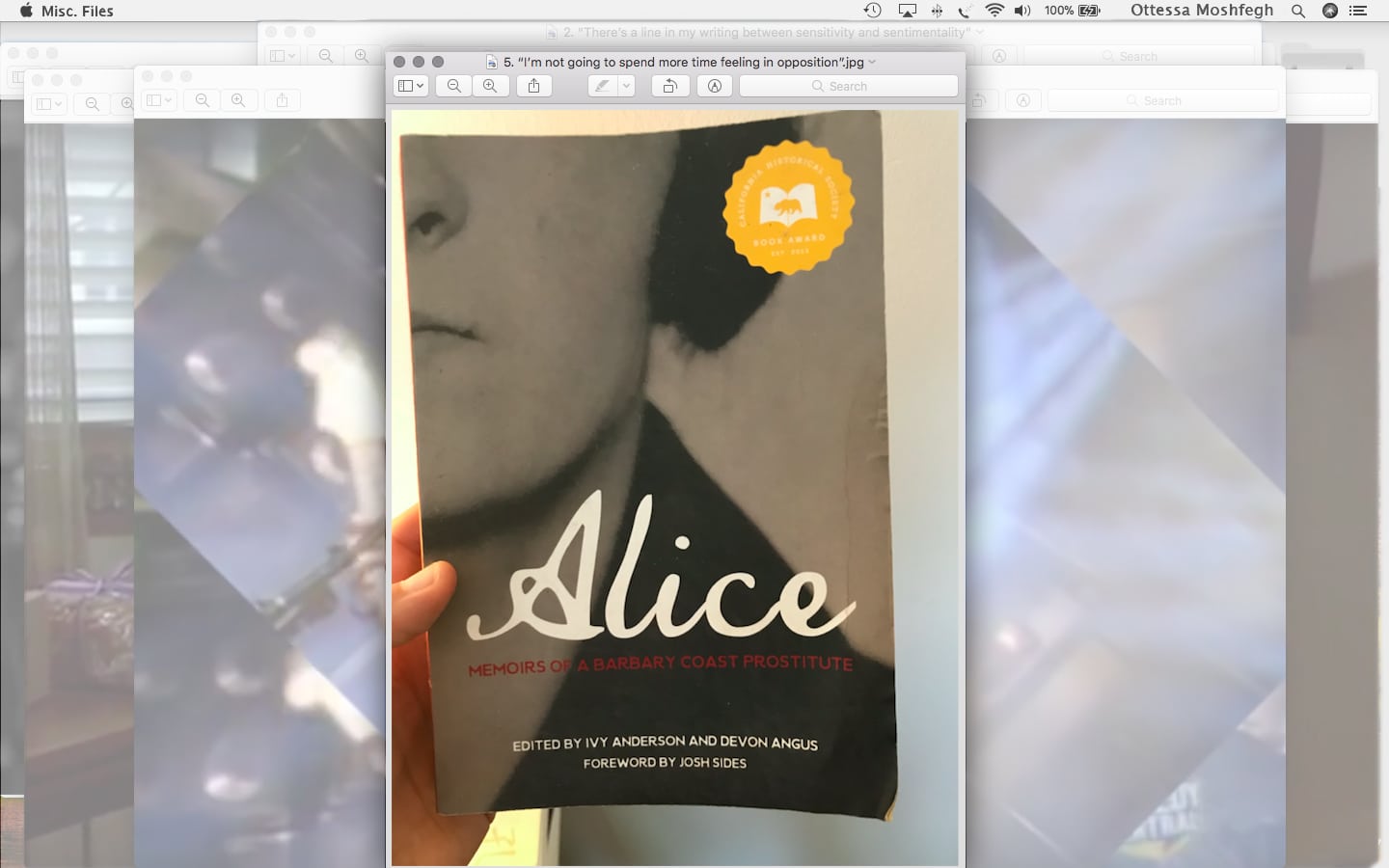

Ottessa Moshfegh: My next book is set in the early 1900s and it’s about a very young Chinese woman who poses as her own brother and moves from Shanghai to San Francisco, where she meets a prostitute of European descent. I’m not from Shanghai, I’m not Chinese, and I wasn’t alive in the early 1900s, nor do I know San Francisco history or the history of prostitution that well, so I’ve been doing a lot of research. Alice: Memoirs of a Barbary Coast Prostitute [is a book] edited out of letters this woman, Alice, had written to a newspaper, in which she explained how she migrated from the Midwest to California with the promise that she would make more money. It’s a very compelling read, but it also holds a deliberate position about women’s labor rights. Prostitution is so often talked about as a moral issue. For those women, it was a moral sacrifice, but they also had absolutely no rights in place that would guarantee them any kind of success as individuals in that kind of economy. You could work eighty hours a week at a Laundromat and still be starving. It makes me think about what’s happening now in the #MeToo era. Everything is a moral issue now too, but the reason this whole thing started was that women weren’t given the same opportunities or paid as much as men in Hollywood. Shouldn’t we get back to that?

Mary Wang: You recently wrote a piece about the experience you had as a seventeen-year-old with a much older male writer. Given the timeframe, it might be counted among a whole host of #MeToo stories.

Ottessa Moshfegh: That story was one that I didn’t know how to write—or look at—for a long time. It was hard to be honest with myself. But this felt like a good moment; I feel accomplished and I don’t care about what that person thinks of me. So I just wrote it and it was good for me. The story is: I had balls. The story isn’t: I was taken advantage of. I was also thinking a lot about the rules of behavior as a moving target, and looking at the last few hundred years, how we’ve developed as a culture in terms of sexuality. I have to believe that perversity isn’t wrong per se. We would not be here if it wasn’t for the entire spectrum of human perversion.

Mary Wang: Is writing the current book different from writing earlier works, like McGlue?

Ottessa Moshfegh: It’s different for each book. But now I know that people are watching me. And I’m more aware of what it’s like to go from conception to writing to editing to publication. Because of that, I’m more interested in the precision of craft and less in the book being another “fuck you.” With all my other books, there was an element of “fuck you.” I feel that, at least this year, I’ve gotten all the “fuck you’s” out of my system. I’m not going to spend more time feeling in opposition. There’s less ego involved now, and more imagination and surprise.

Mary Wang: That sounds liberating.

Ottessa Moshfegh: It is. And it’s beautiful to be working toward a higher level of craft. After I wrote McGlue, I stopped worrying so much about aesthetics. Now I’m worried about aesthetics again, and this book feels like a return to a mindset from ten years ago. In order to convey the story, I need the language to be evocative of a certain light, of a certain shade, of the way things move. I need it to be accurate.

Mary Wang: Was it necessary to have written a certain amount to get to this stage?

Ottessa Moshfegh: I’ve been learning a lot from everything I’ve written. I wrote McGlue in grad school, but it’s not as if someone taught me how to do it. People in institutions can be good mirrors and cheerleaders, but I don’t think anyone can teach you how to write. I don’t even think reading can teach you how to write. You have to attempt something to get your brain to teach itself. And I feel that I’ve done that. I know this much now, and I endeavor to know that much more. I hope this book teaches me that.