Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Namwali Serpell’s novel The Old Drift begins with a chorus of mosquitoes. They help narrate the epic tale of three families in Zambia, where Serpell was born. A colony of the flying little buggers buzzes between chapters, gasping and delighting at the silliness of the story’s human characters, spreading hive-mind wisdom along with infectious disease. “To err is human,” the mosquitoes exclaim. “Obey the law of the flaw.”

True to their claim, the mosquitoes’ first line in the novel contains an intentional misspelling of a Nyanja word, one of the many languages spoken in Zambia and in the novel. The logic of the productive mistake also guided Serpell herself, she explained when we spoke on the phone in December last year. Serpell, who also works as a literary critic and academic—she now teaches at UC Berkeley—has a rigorous creative practice packed with accidents, errors, and other forms of “unselfconscious creation.” It has yielded a nearly 600-page saga, which spans an entire century and three different genres: magical realism, social realism, and science fiction.

The story opens in a colonial settlement in the early twentieth century, in a territory of what was then called North-Western Rhodesia, where newly arrived Europeans and some locals attempt to approximate a society on the banks of the Zambezi river. Serpell began the narrative of her country here because, as the mosquitoes tell us in the novel, “This is the story of a nation—not a kingdom or a people—so it begins, of course, with a white man.”

It’s also where the three multi-cultural families who populate the novel embark on their entanglement with politics, history, and each other. They migrate across continents; they raise their children in foreign lands; they live through revolutions and epidemics. But, tragically and hilariously, none of their foresight is a match for that of the mosquitoes—who seem set to outlive them all.

Reading The Old Drift often felt to me like the act of writing, each sentence caressing me for attention. True to the spirit of its winged narrators, the book’s abundant, tentacled lines seduced me into reading them over and over, just to feel them tickle my senses once more.

1. “It’s just this beautifully accidental combination of things.”

Mary Wang: You sent me such a treasure trove of materials, a Google Drive folder more abundant than what we can fit here! I got a sense from reading The Old Drift that you’d have a wonderful archive. What’s the relationship between writing and research like for you?

Namwali Serpell: Some might believe that writers conduct research in earnest—they gather materials, do interviews, read books, take notes. And then there’s a moment of integration where they put it all together and write the story, which includes all of those bits and bobs. My process is a lot less straightforward. For me, research is part of a process of ongoing interruption with the writing. For The Old Drift, I would start writing from the perspective of a particular character, and an image or an object would pop into my mind, and I would need to make sure that my memory of that object or my understanding of it was accurate. Mostly, I go online, and sometimes I find books and read them and incorporate pieces that feel right or needed.

So the folder that I gave you is more like a jumbled drawer than an organized set. Even though my writing incorporates many different kinds of genres, including speculative fiction, it always feels to me like the pursuit of persuading the reader of what’s possible. Historical and scientific details are very important to me in trying to make sure that the reader stays convinced. So the research is a way of creating this texture of reality that undergirds the flights of fancy in the novel.

Wang: You describe it as an interruption. Is it a pleasurable one?

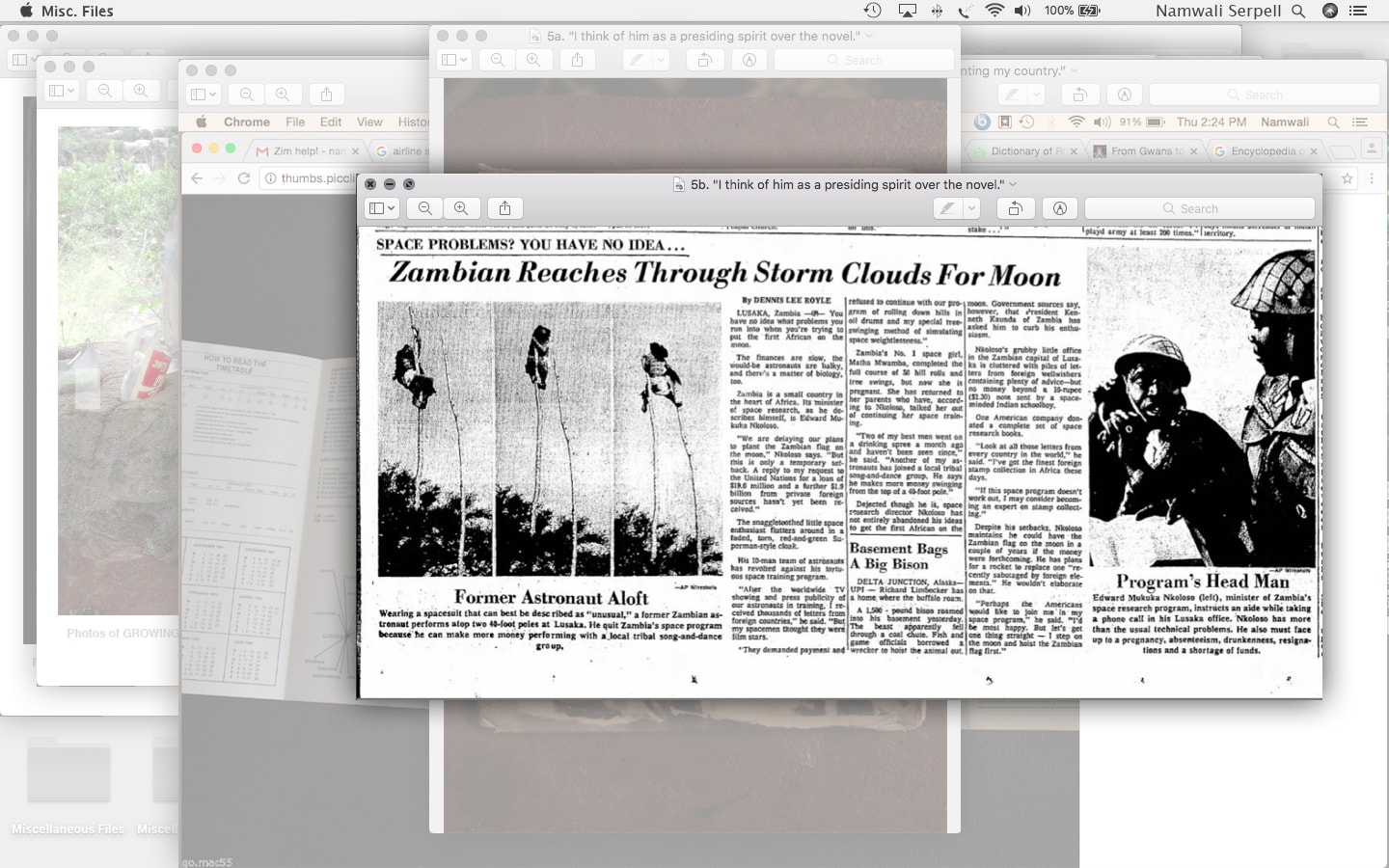

Serpell: Yes, I love research and looking things up! In the case of the Zambian Space Program, I was able to make a very fortuitous comparison between the research process for the novel, and the one for my nonfiction work of journalism on the subject. I wanted to write about the program in my novel, and started doing research, including library research, looking at newspapers, going to the archives, and doing some interviews. At a certain point I gathered enough information that I believed I should write a nonfiction piece, too.

But the fact-checking that I went through for the resulting piece at The New Yorker, and my efforts to verify specific historical details so that I could make my argument, were very different from the kind of exploratory, interruptive, haphazard process that I embarked on for the novel. Writing the article, there was due diligence involved: you have to set up contexts, like the political circumstances under which Edward Mukuka Nkoloso, who launched the Zambian Space program, was working. It’s geared toward a different kind of persuasiveness.

At heart, I am definitely a fiction writer; the details I garnered that I found most exciting were for the novel. So I find the research for fiction writing absolutely delightful, but I find the research for journalistic writing extremely stressful!

Wang: In the novel, you point out the etymological relationship among the words “generate,” “gender,” “generation,” and “genre.” Each generation of characters is narrated using their own genre, and you wrote the novel over the span of 19 years, in which you yourself moved from one generation into the next. Can you trace the growth of yourself, as a person, in this novel?

Serpell: I don’t write in order, so the earlier parts of the novel don’t correspond to a younger me. But there are lines that I wrote when I was 20, and there are lines that I wrote last year. So there’s definitely a multiplicity of Namwalis, like the presence of tree rings, if you were to cut through the middle of the novel. I decided to preserve certain attachments I had as a younger writer rather than editing them out. I can’t remember who said this, but it’s something like, “Trust the rawness of your first draft.”

An example is my relationship to magical realism, which was at its height when I first started writing this novel. During that particular period, I was really focused on figures like María Luisa Bombal, Gabriel García Márquez, Salmon Rushdie, and Italo Calvino. If I were writing the novel now, I would not necessarily have written the three grandmothers as magical-realist characters. But I decided to preserve that part because, for all I know, in 10 years I’ll be attached to magical realism once more. The younger Namwali is most evident to me in that part of the novel, and I feel a kind of tenderness for her. Magical realism is very dark, but it also has a kind of openness to beauty. And I like that about my 20-year-old self.

Wang: I wonder what roles dreams play in your writing process. You have said before that both “The Sack,” your short story, and one of the final scenes in The Old Drift were based on images that came to you in dreams.

Serpell: Talking about your dreams is always attended by the specter of boring your interlocutor, because a dream is only ever truly vivid and interesting to the dreamer. So I always hesitate to say that I get inspiration from dreams. But on a fundamental level, I’ve always believed that dreaming is a form of unselfconscious creation, insofar as you conjure these scenes, figures, and images, but there’s no presiding intention, no authorial force, putting it together. It’s just this beautifully accidental combination of things. It can also make you feel, if you’re a big dreamer, as strongly as you feel when you go to the movies or read a book. Trying to capture the feeling of a dream on the page is a highly specific enterprise. It’s not the same work that I do when I’m creating a scene or developing a character. It’s a very specific part of my creative process that I find hard to describe, but that feels really legit to me. In some ways, it’s the closest thing to reading, because I feel that I have vetted this image as effective, as something that gave me chills when I was asleep.

Wang: I think “enterprise” is a good word to use here. To be able to observe and use dreams is a skill. I often envy friends and loved ones who are lucid-dreamers and can steer their dreams.

Serpell: I don’t actually want to steer them, because that defeats the purpose for me, which is to be in a completely receptive state. I always find flying dreams really remarkable—for human beings to extrapolate from what it’s like to jump and fall, and from seeing flying animals, to having dreams in which they’re flying themselves. I’ve noticed that when I’m on the verge of waking up, and I try to fly, I can’t. The passivity is actually part of why I love dreams so much. I don’t use every dream—I don’t even have a dream diary. But there are some dreams that are so striking, so compelling, that I feel like they’re gifts: I’ve been handed a scene or an image from some other part of my mind.

2. “What had started off as a joke about writing the great Zambian novel began to feel more and more like a responsibility.”

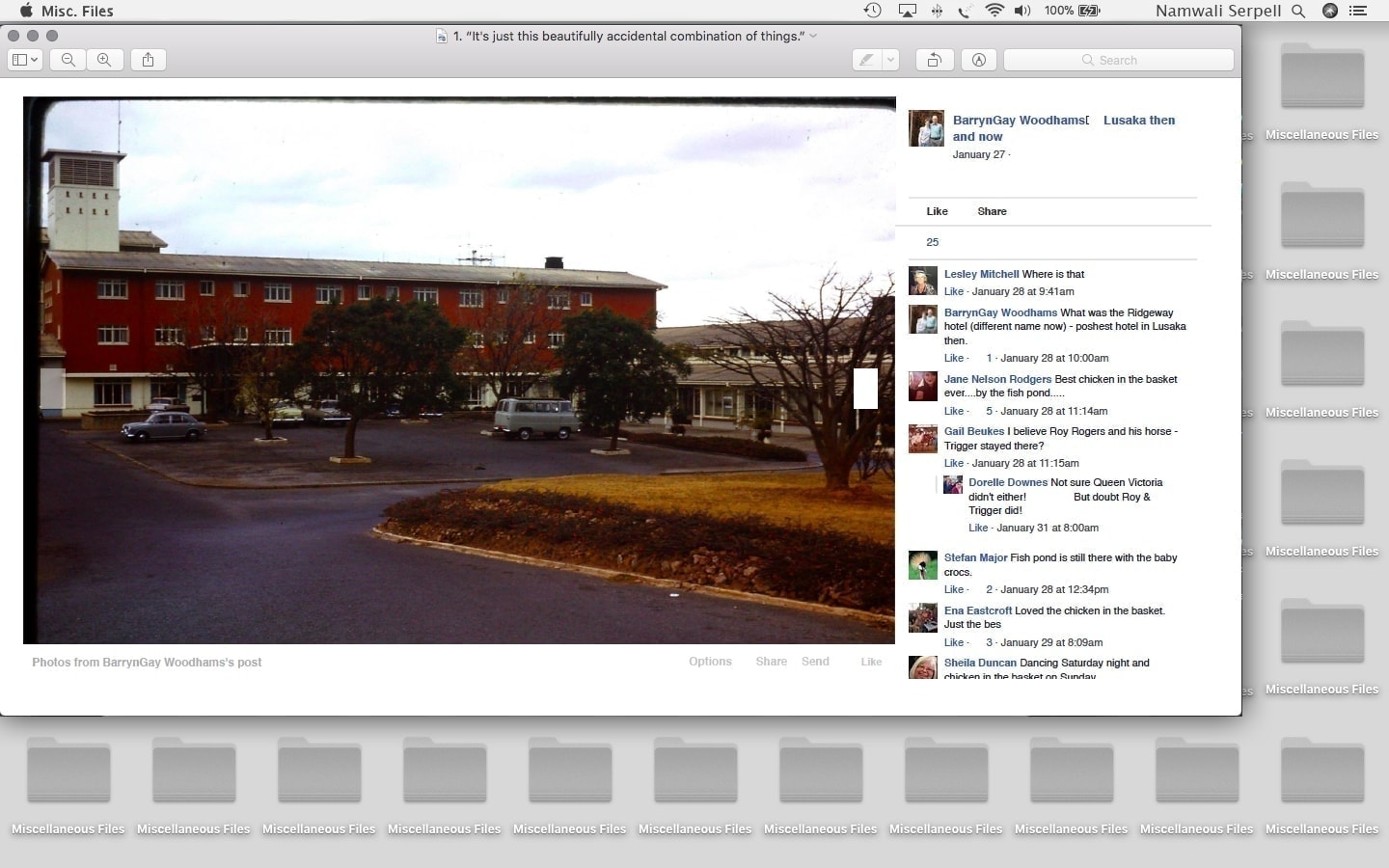

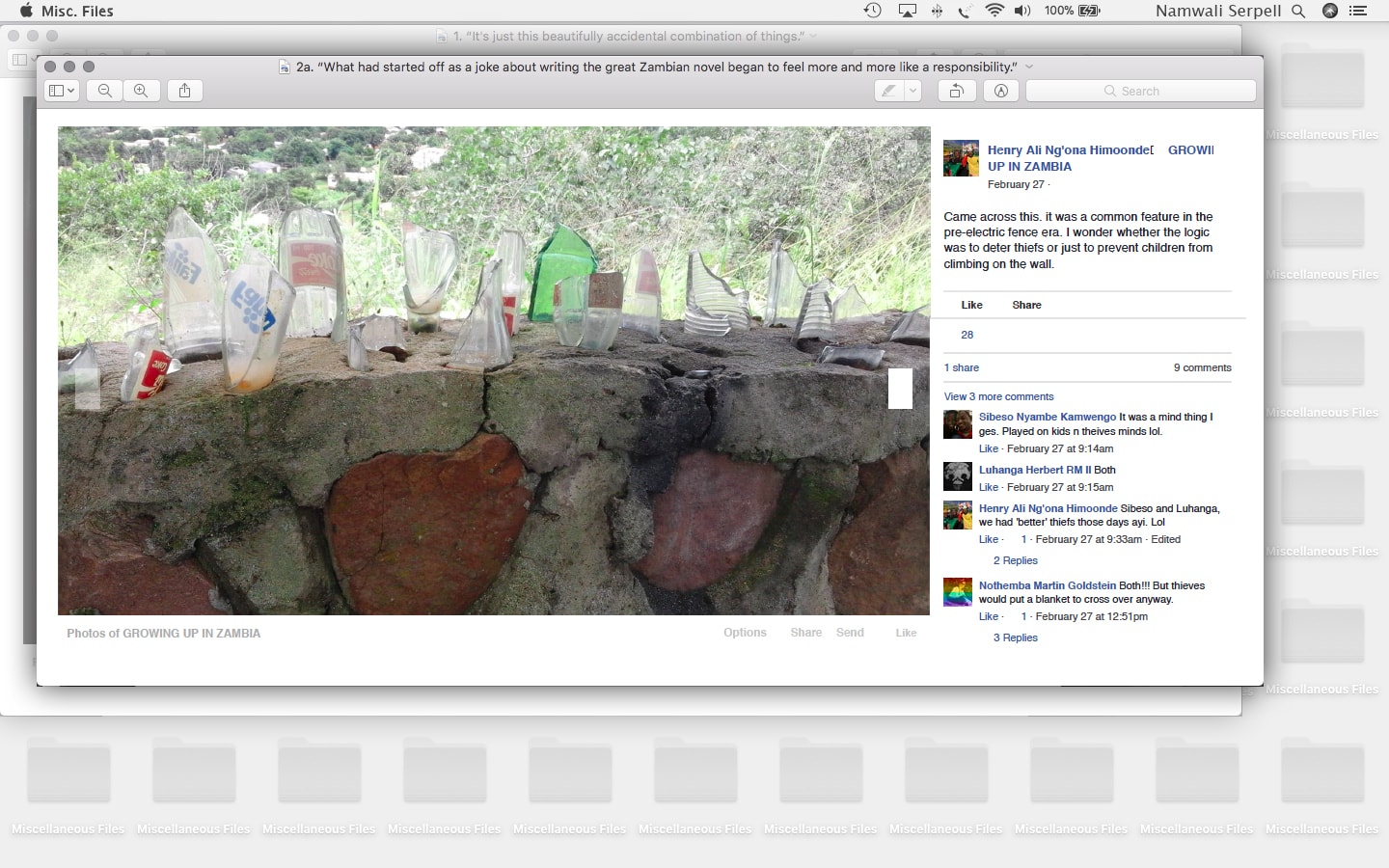

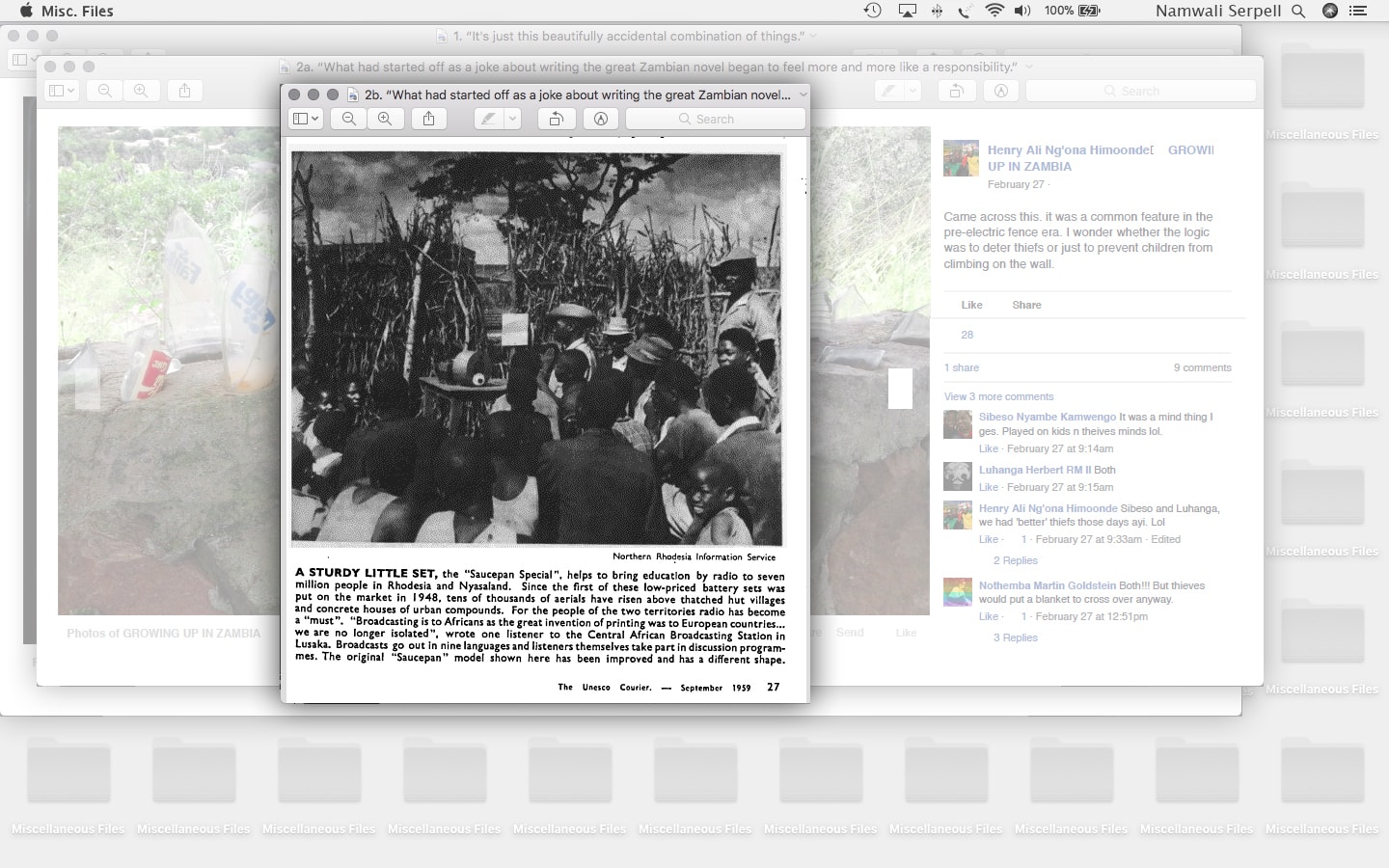

Serpell: These images are screenshots from Facebook groups dedicated to Zambian nostalgia. Some of them are posted by historical societies, and they’re about fun times in Northern Rhodesia from the 50s or 60s; some are just people posting photographs from their family collections as a kind of nostalgia project for themselves. I found that immensely useful. A lot of the images that Americans have from the ’50s and ’60s are pulled from popular culture—from magazines, TV shows, or photography books. But in Zambia, we just didn’t have that. What we had was families taking pictures. There are also photographs of things that people have looked up on the internet as a way to spark memories in other Zambians, like a picture of a certain kind of pop drink we had when we briefly stopped importing sodas and beverages from outside the country, or a photograph of the broken glass built into the top of concrete walls as a way to keep thieves out. I didn’t participate in this, because I left Facebook a while ago. But I took screenshots of these images, because they felt to me so evocative of the textural detail of everyday life in Zambia. They helped me remember certain things in the parts of the novel that I was alive for, and they helped me pinpoint things I wouldn’t otherwise have known, like the fact that we used saucepan radios in the ’60s and ’70s.

Wang: When I was looking through the larger folder you sent me, I found a photo of a kid flipping their eyelids inside out. It’s funny how cross-cultural some things are: apparently there’s a moment around nine years old when a kid develops an instinct to flip their eyelids!

Serpell: Exactly! There are moments in the novel where I include something that people all over the world do, precisely because I wanted people to make that connection. As a kid, I used to tuck the hem of the cute dresses I wore into the sides of my underwear in order to climb trees. [Naila, a character in the novel, does this.] And that’s something friends from other parts of the world have described. I’ve also read about it, for example, in American novels about the South.

Wang: You mentioned that there wasn’t much pop-cultural documentation of daily life in Zambia. But at the same time, you have written that one colonial legacy the British left is a propensity for paperwork, which resulted in extensive archives. So there’s a gap between institutionalized documentation and what exists outside of it.

Serpell: There’s a difference [among] record-keeping, the archive, and collective memory—all three have very different relationships to preserving daily life. My understanding of life in Zambia in the ’70s, before I was born, is very much colored by my own biases. I believed people there couldn’t possibly have been as progressive or dynamic and Americanized as my generation. But then I interviewed my mom, and she talked about mini skirts, afros and the Beatles. So the interviews supplemented this gap.

Wang: There’s one version of history you have stored in your memory, and probably another that came to you through textbooks in school. It seems there was yet another version that you acquired in the process of writing this novel.

Serpell: Yes, absolutely. When I started this novel, all I knew of Zambia was from my childhood there, my family stories, and a little bit from the history books. That is part of the reason the novel took so long. It was the first novel I started writing, but not the first novel I finished—that one will probably be my second or third novel published. What had started off as a joke about writing the great Zambian novel began to feel more and more like a responsibility. Simply inventing lives and relationships and people didn’t feel like enough. I really wanted to create a vivid sensory world that felt right to the people who have lived there. It’s been really great to meet readers who say that I’ve captured a certain quality of life in Zambia; it’s really satisfying to hear that the amount of effort that I put in to try to get those details right has paid off, at least to some readers.

3. “It’s always going to exclude someone in some fashion, which is in itself a kind of inclusion.”

Wang: There are so many languages in the novel, and even so many Englishes, from Zinglish to British to American. I wonder what you consider your mother tongue, and whether it differs from the language you use to write?

Serpell: It’s English, but it’s Zinglish, really. I learned very quickly on book tour that I could not read the narrative voice of The Old Drift out loud in my American accent, because it just sounds wrong. So I’ll read in Zinglish, and I’ll try to take on the inflections of the characters when I’m reading pieces of dialogue. There are two languages in the novel that I don’t know at all, which are Italian and Telugu. For those parts, I relied heavily on friends who are fluent. I know French very well, and I know two different Zambian languages not very well, but enough that I could sprinkle pieces of Nyanja and Bemba into the prose. But the Englishes I have are my playground, and thinking about Zambian tendencies with English and trying to render those on the page was really delightful!

Wang: This Nyanja Basic Course is fascinating. The introduction, true to the spirit of The Old Drift, starts by discussing the mistakes in the course, which is not something that most language textbooks acknowledge.

Serpell: One of the problems with learning Zambian languages through the written word is that the transcription of different sounds has been very erratic. The missionaries who created the first local-language Bibles, for example, had very different spelling conventions than the colonial officers, who had very different spelling conventions than the people who took up the official documentation of Zambian language in writing. So you’ll find different dictionaries with different spellings. In fact, I had a long conversation with my father, who learned Nyanja, the dialect of Chewa spoken in Zambia, to do his research in the Eastern province. And one of the first words in the book, at the very end of the first transcription of the mosquitoes’ whining, is “zo’ona.” It means something like a non-religious “amen,” or “so it is.” It’s usually spelled “zoona,” so any reader of English would think to pronounce it as “zoo-nah.” But the cadence of the word—“zoh-oh-nah”—is so important to its rhythm and to its effect, which don’t come through in how it’s usually transcribed in English. So I decided to put an apostrophe between the two O’s, but that’s technically incorrect. Any Zambian linguist would tell you that.

Wang: There are so many languages and linguistic systems in the novel that most readers will end up not understanding part of it, which is its beauty.

Serpell: Yeah, I’m okay with that, especially because that includes me! I mean, I know the Italian that’s in the novel, but if I was asked to recite the Italian sentences off the top of my head, I couldn’t do it. So it’s always going to exclude someone in some fashion, which is in itself a kind of inclusion.

Wang: Let’s talk a bit more about your fact-checking process. I imagine that it must have been a lot of work for you.

Serpell: Yes, especially because nobody else could really do it. I said in an interview with The New Yorker that the only person that could have fact-checked the large majority of novel was my mom, who passed away before the novel came out. She had done HIV/AIDS research, she spoke Bemba, she grew up in Zambia, and she was one of the first women to be educated at the University of Zambia. So these elements of the novel that seem like a random assortment are things she actually could have fact-checked. I had to do most of it on my own and then outsource it to different friends. I went to Tirupati in India, and I’ve been to Italy and England, so I did make the effort to go and be in those places. But I still got a lot of the details wrong, and I’m very grateful to be corrected by my friends who are native to those places.

There’s also been a lot of retrospective fact-checking from readers. Someone very kindly said, “I love the book, but just so you know, tennis balls were white in 1962 and that might be of interest to you!” So in the second edition of book, I changed a yellow tennis ball in Agnes’s court in her home to white. My dad pointed out a kind of a geographical error that Percy makes, which I took directly from Percy’s own memoirs. And my Dutch translator had masses of questions, many of which can’t be found on Google, because there’s no official documentation of a lot of Zambian cultural products and ideas. She also found certain misspellings of Zambian words, which I took from Western history books, which were wrong. So there are about a hundred or so changes between the first and second editions, as a result of this outsourcing of fact-checking to a community of readers!

4. “That made me feel that I could be, and should be, irresponsible in representing my country.”

Wang: I love how the mosquitoes’ line, to err is human, keeps coming back in this conversation. It makes me wonder how you deal with errors as a writer. Are they useful for you?

Serpell: There are different kinds of errors, right? There are errors that characters make, there are errors I make, and there are errors that get inserted accidentally during the editorial process. I have a very different relationship to all of them. I almost always find my own errors productive. Sometimes they teach me something about my own biases, and often the correction yields something really interesting. The person who sent in that correction about the tennis ball said that it’s perhaps unsurprising that the British upper classes held on to a white ball even after it was made yellow for matches in the seventies. It fits very much with the purity of the “tennis whites” that women are supposed to wear, and it’s a huge part of how Serena and Venus [Williams] have had to battle to wear whatever they want, for instance.

An error of a different kind appeared in my first short story “Muzungu,” which appears in the novel as Isabella’s first chapter. At its very end, there’s a scene between this young girl who’s just been called a muzungu (white person) for the first time. To reassure her, a black Zambian gardener tells her that muzungu means “ghost,” and he aligns that ghostliness with Casper the Friendly Ghost, because he knows that’s something she will feel comfortable with. In fact, muzungu does not mean “ghost,” and one reader was very upset with me for having this “false etymology” of the word in the story. But there’s this thing in literary theory called “dramatic irony.” The reader is supposed to recognize that this is a false etymology, and that the character is saying it to the little girl to try to make her feel better. And it’s a gardener in a relationship with the girl living in the household that he works for, not a university professor offering an etymology of a word. This presumption that my character shouldn’t be wrong or deceptive bugged me, as did the presumption that the purpose of a novel about Zambia is to convey “true anthropological information.” So that made me feel that I could be, and should be, irresponsible in representing my country.

In the end, I didn’t do that by including a whole bunch of errors, but by including speculative fiction. It also made me decide to include, elsewhere in the novel, the real etymology of muzungu, which is to wander around in circles until you’re dizzy—a very accurate depiction of what white visitors to Africa in the early days must have seemed like to locals. And so having that error brought to my attention allowed me to think about the narrative voice of the mosquitoes as having access to etymological information instead of entomological. So there are countless mistakes that actually led me to something more interesting.

Wang: One error you make very productively in the novel is that of the pun, which is simply a language error gone right.

Namwali: I know it’s an acquired taste, but the pun is one of the true delights of my life!

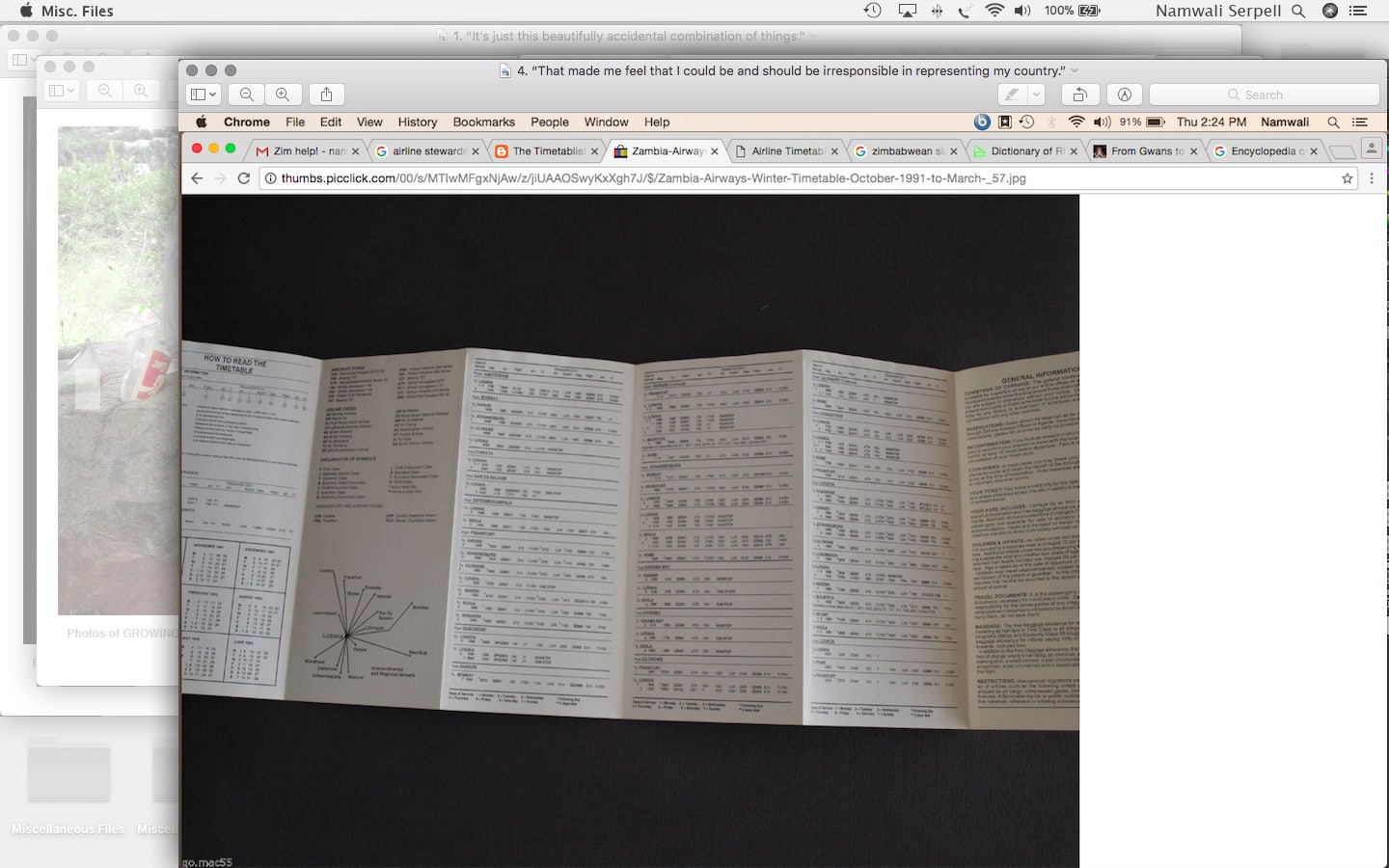

Wang: What do we see in this image?

Serpell: I wanted to write a scene on the flight between Lusaka and Harare. I got some details about what those planes are like from Zambian Airways commercials I found on YouTube, and I heard stories from people in interviews. But it was important for me to get a sense of how long those flights were, and what time of day they would arrive in one city or the other. I couldn’t find the information I needed, and finally, Google took me to eBay. There are collectors of flight memorabilia on there who sell pamphlets with flight schedules from that time and, luckily in this case, to demonstrate its authenticity, they took a photograph of the inside of the pamphlet. So in the end, I didn’t even have to buy it! I did the same thing in trying to figure out when He-Man figurines came to Zambia, or when bungee jumping first started at the Victoria Falls. I had to make this giant spreadsheet containing timelines of all characters, just so that I could make sure that when this character was bungee-jumping, it actually existed.

5. “I think of him as a presiding spirit over the novel.”

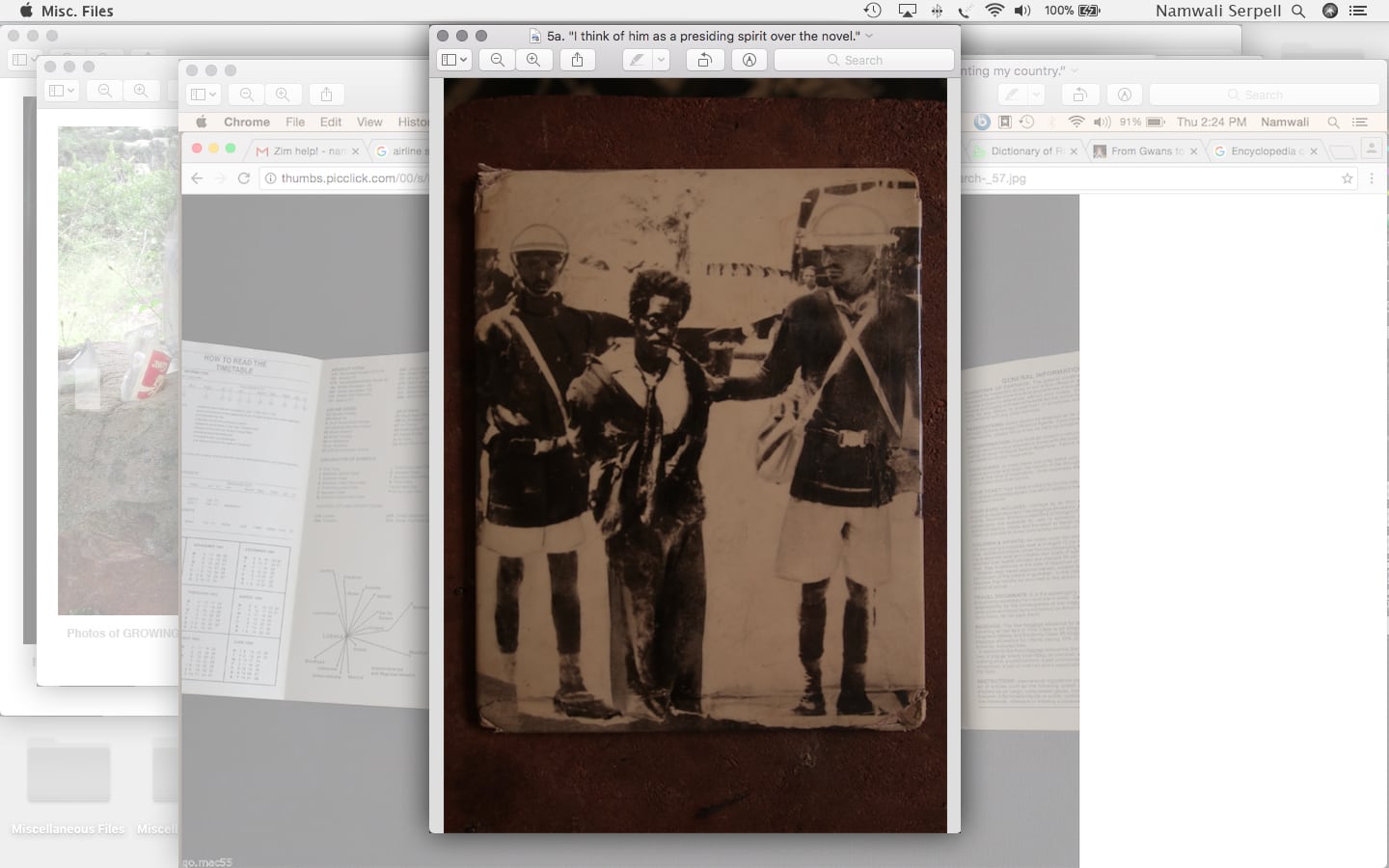

Wang: I wonder why you’ve chosen this photo of Edward Mukuka Nkoloso, who launched the Zambian Space Program and is a character in the novel. I can imagine that there are a lot of striking images that have come out of the program—whether it’s him rolling the cadets down a hill in an oil drum to simulate weightlessness, or a picture of Matha Mwamba, the sixteen-year-old girl cadet, and her twelve cats, which were supposed to travel to Mars with her.

Serpell: Nkoloso said in his first press conference that the program was going to put Zambia on the world map, so there was a sense that the nation had the right to step into the space race between the US and Russia. It was a kind of nation-building enterprise, and it was based almost entirely on image. But this photo is from before he created the space program, and it’s of uncertain provenance. Back then, he was a member of the African National Congress, which was the political party that would eventually become the United National Independence Party (UNIP). Nkoloso staged a kind of civil-disobedience campaign in the north of the country, trying to convince farmers not to buy goods from European-owned stores and to refuse orders to burn their crops, which was a common agricultural practice that was dictated by local chiefs and colonial administrators. He was technically under house arrest for having participated in some strikes in the mining district, so the colonial administrators and local chiefs put out a warrant for his arrest. The community hid him a few times; one time, he purportedly dressed as a woman. But the authorities eventually caught him and dragged him to a local school, where they conducted a fake prosecution. Students were incited to call him a traitor and a thief and a liar. His head was shaved, and on the road between the school and the jail, he was knocked into the water and nearly drowned.

It was reported in the administrative archives that a photograph was taken of him, which was also a form of capture, because this was a moment of humiliation for him—he’s quite bedraggled in this photograph. However, I did not find it in the archives. I was given a scan of it by another researcher, who got it from Nkoloso’s son, I believe. So it’s unclear to me whether this is a fake or real photograph. But it’s very striking to contrast this against the image that we have of him from 10 years later when he’s running the space program, where he’s wearing his combat helmet and his cape, and he has this visionary appearance.

Wang: You want to start a digital archive around him.

Serpell: Yes, I have a lot of scans of his correspondence from the archives. Not just from the National Archives of Zambia, but also the UNIP archives, which have not been organized, even chronologically. They’re in a heap in this warehouse. I spent a lot of time digging up traces of his words in his letters, his telegrams, so it feels like it would be worthwhile to organize and display them somehow. I find him such a fascinating figure. I think of him as a presiding spirit over the novel: he has this historical and political significance, and he also has this Afro-futurist, speculative significance. And he combines it with a deeply Zambian, somewhat quirky sensibility. It feels like his story would be worth telling as a precursor to Afro-futurism, a term that wasn’t coined until 30 years after his space program. So I’m thinking about creating a combined biography and digital archive that will complement each other, so I can tell the parts of his story that I didn’t get to tell.