Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Leanne Shapton understands that negative space—whether on a canvas or in a short story—is as important as what’s in the foreground. Her writing has a certain painterly gaze; she often leaves sentences unfinished, events untold, and spaces blank—whether in Swimming Studies, an autobiographical account of her experiences as a competitive swimmer; Important Artifacts and Personal Property from The Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry, an intimate study of a couple’s broken relationship in the form of a fictional auction catalog; or Women in Clothes, a book she made with writers Sheila Heti and Heidi Julavits about how and why women get dressed. Shapton takes a similar approach to her work as an illustrator, creating characteristically precise book covers for works by Alice Munro, Jane Austen, and Virginia Woolf. It’s true, too, of the books she both writes and illustrates: In Was She Pretty?, an exploration of jealousy, Shapton evokes a collection of other people’s exes through nonchalant black brushstrokes and a few lines of text.

The pleasure of diving into her work comes in part from the way she relies on her audience to interpret things—things that might be visible, or might not—and the way she creates an open space that invites the reader to practice a form of empathy as profound as her own. As she writes in a spare yet specific description of a swimmer in Swimming Studies, “In lane one is an eighteen-year-old vegetarian who keeps spiders as pets. Her mother died of cancer when she was twelve.”

In Guestbook: Ghost Stories, published in March, Shapton takes her exploration of absences even further, with a collection of short stories that addresses guests, ghosts, and other lingering presences in our lives. The stories take varied forms: One is a page-long hearsay relaying a mysterious tale told at a party, while another—a haunting account of the life of an estate and the generations of family members who have occupied it—is mostly narrated in photo captions.

I visited Shapton’s Garment District studio on a bright Tuesday in early spring. The intimate space—in which every inch seemed designated for the storage or application of art materials—reminded me of what I imagined artists’ studios would be like in New York, but which started disappearing long before I arrived in the city five years ago. Original editions of artworks hung on the walls; motley scrapbooks Shapton found on Etsy were piled on tables; and bottles of champagne were lined up in a corner, a stash left over from the Christmas party she hosted. Though she had earlier emailed me some photos from the process of making Guestbook, when I arrived I found she had also printed them out. Throughout our conversation, her hands rearranged the print-outs, leafed through pages of books, and pointed me to small details, like the texture of a collage she urged me to touch. We talked about her relationship to fashion, the connection between athletic training and the artistic process, and about the methods she uses to combine the visual and textual parts of her work. We talked about the latter so enthusiastically that, as I was leaving, we joked that this interview should be sponsored by Canon and Adobe.

All photos are taken by Mary Wang, except for Shapton’s photo above, which was taken by Derek Shapton.

1. “I just find that so beautiful, that glue and the awkwardness of the cut paper.”

Mary Wang: What were the first images that inspired you to make Guestbook?

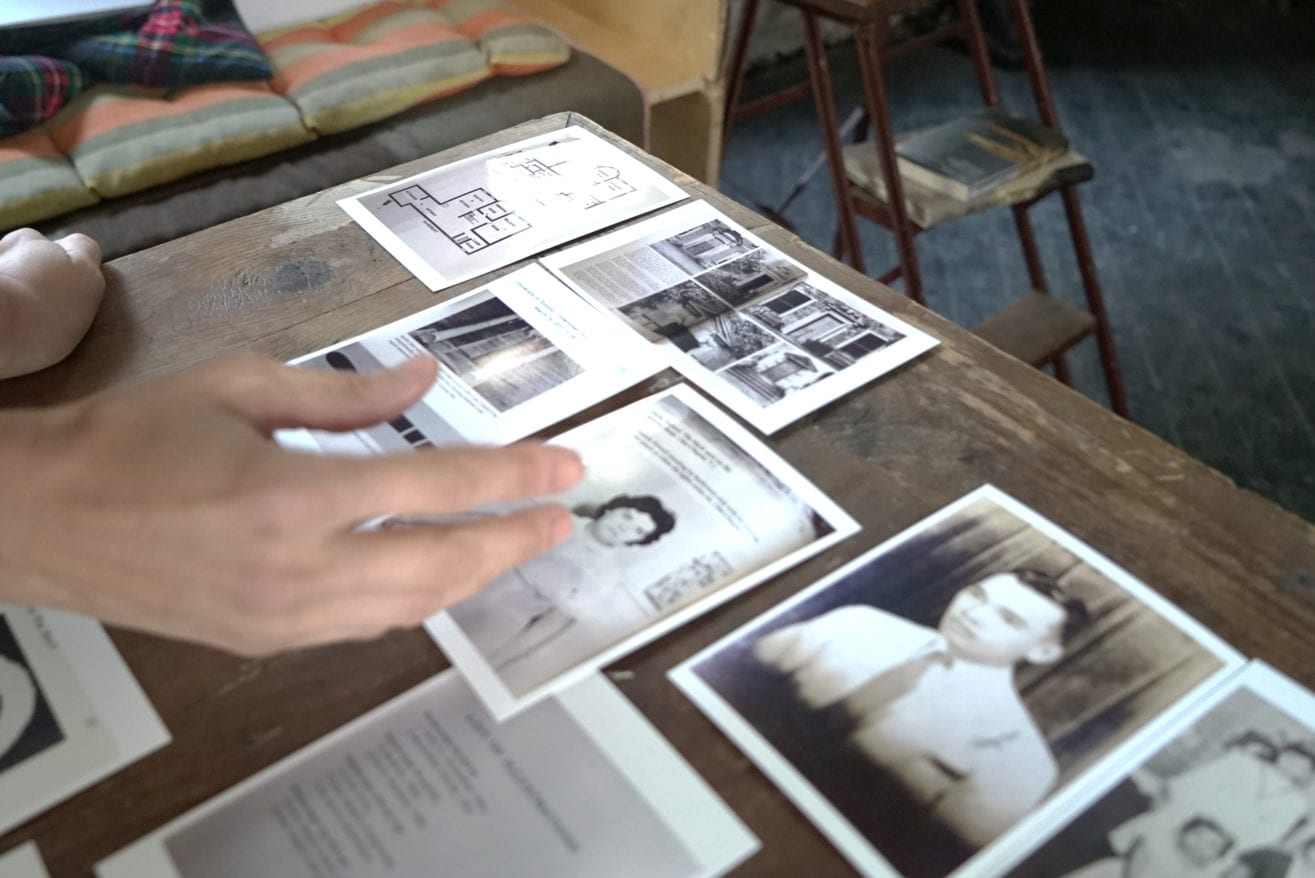

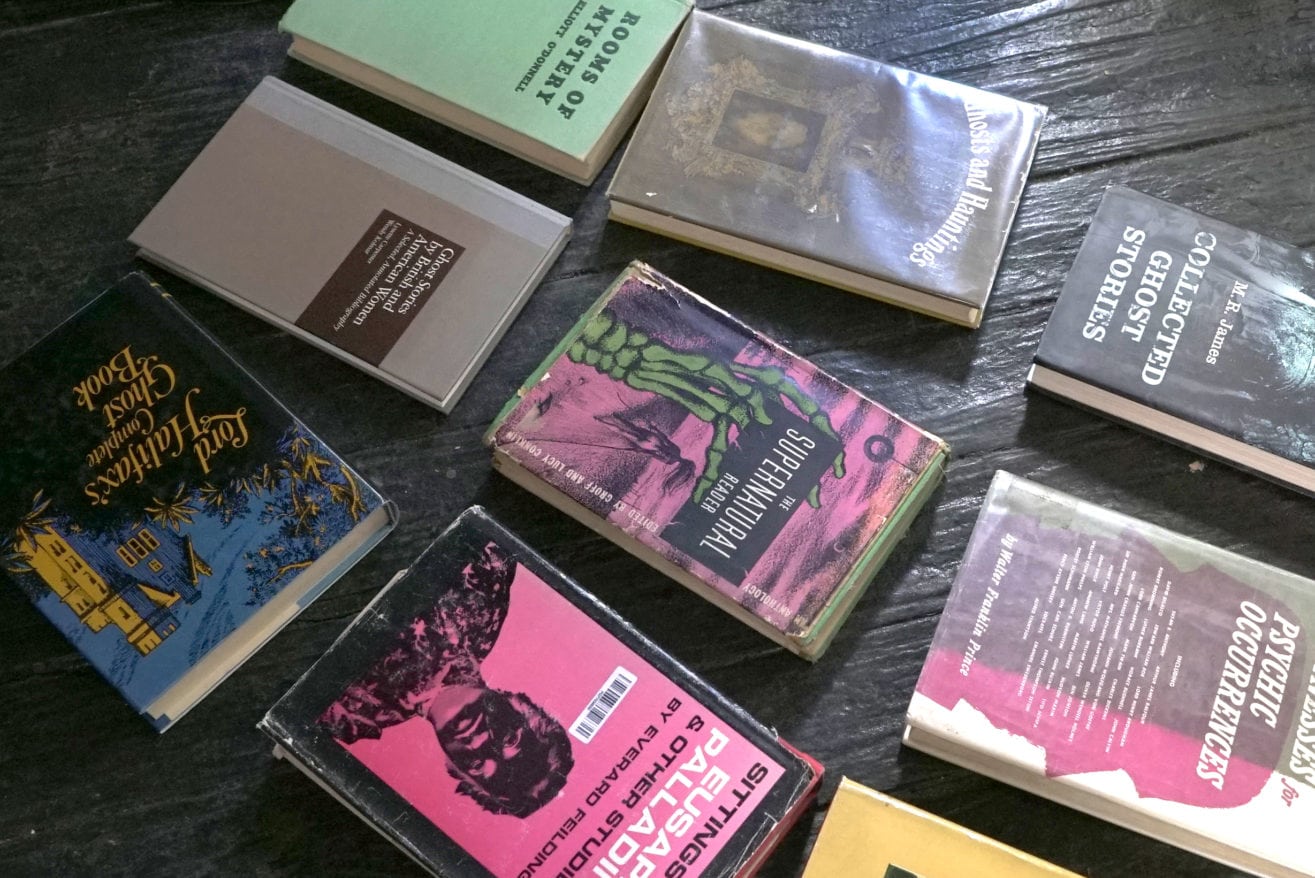

Leanne Shapton: Probably these pictures I took of books about haunted places or ghost hunters. They have captions like, “The knife that spontaneously shattered into four pieces in Carl Jung’s home.” The tone of that writing was so important to me—the mix of proof, shock, and totally crappy images. I also started looking at old nonfiction books, which contain floor plans, architectural details, and specific book conventions, like lists of illustrations. There are probably thousands of photos I took during the writing of the book. And then came the question of which pictures I’d shoot and which I’d use from my own collection. These were for the story S as in Sam, H, A, P as in Peter, T as in Tom, O, N as in Nancy, this idea of using my own family pictures. That’s my mom, this is my great-great-grandfather Leandro, who is my namesake.

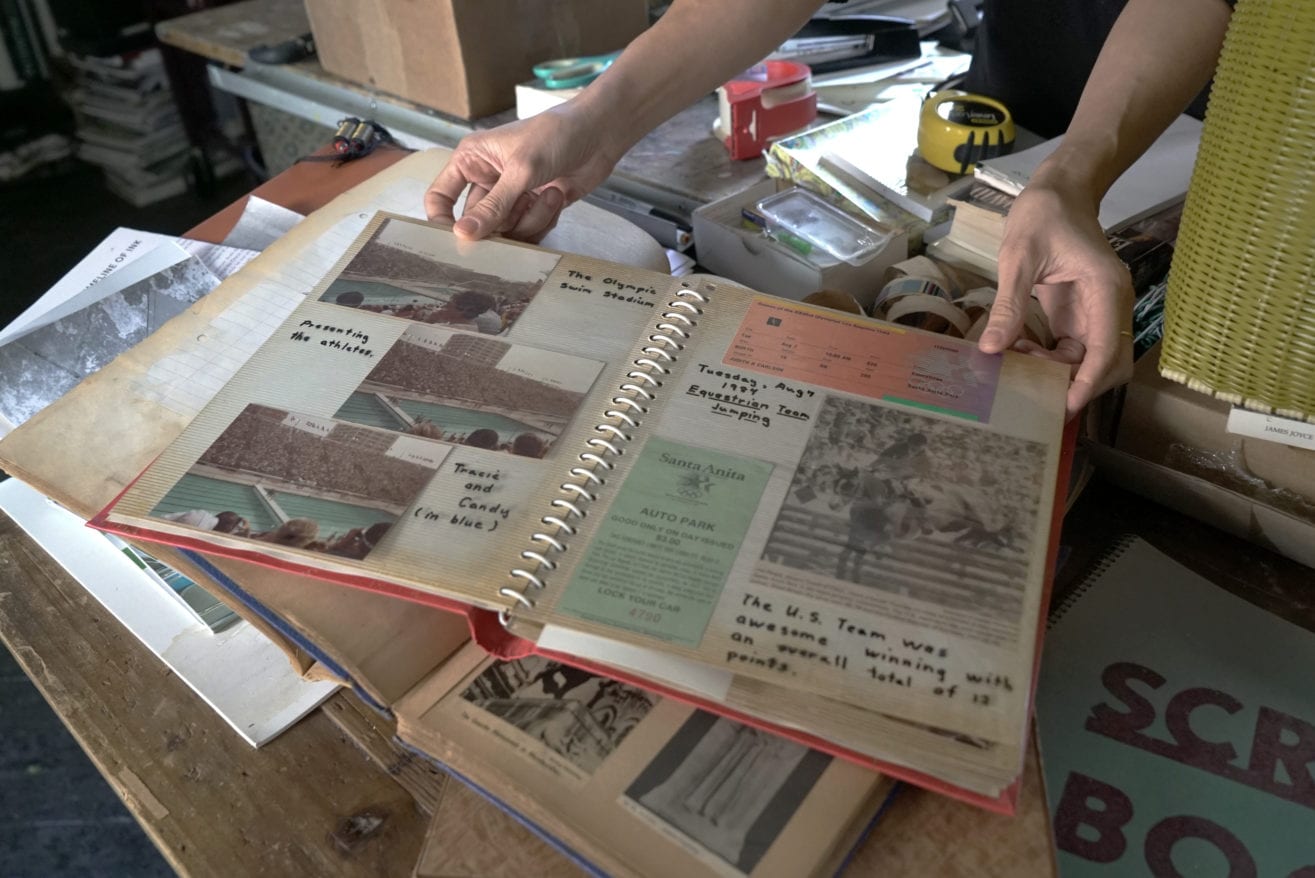

I also looked at guestbooks and scrapbooks like these. I mean, look at this! Isn’t that gorgeous? I bought these on Etsy and eBay because I wanted to see how people organize their own personal images. One of them is somebody’s scrapbook from the Los Angeles Olympics—I was specifically looking for pictures of pools, like these, for one of the stories in the book. These really give you a sense for people’s layout proclivities. I just find that so beautiful, that glue and the awkwardness of the cut paper. Feel the texture of that! And those holes on the side, I think they’re from termites!

I also look at a lot of references when I’m designing covers. When I was working on the cover for my book, I went to the Warburg library and took pictures of the books there. I would have versions of my covers on my phone to poll people. The text in one version came from a Roosevelt Hotel Bar menu—my friend, the designer Teddy Blanks, helped me to turn it into a font.

2. “We’re all buying into this idea that these photographs mean something, when really they might not.”

Wang: How did the stories from Guestbook come about for you?

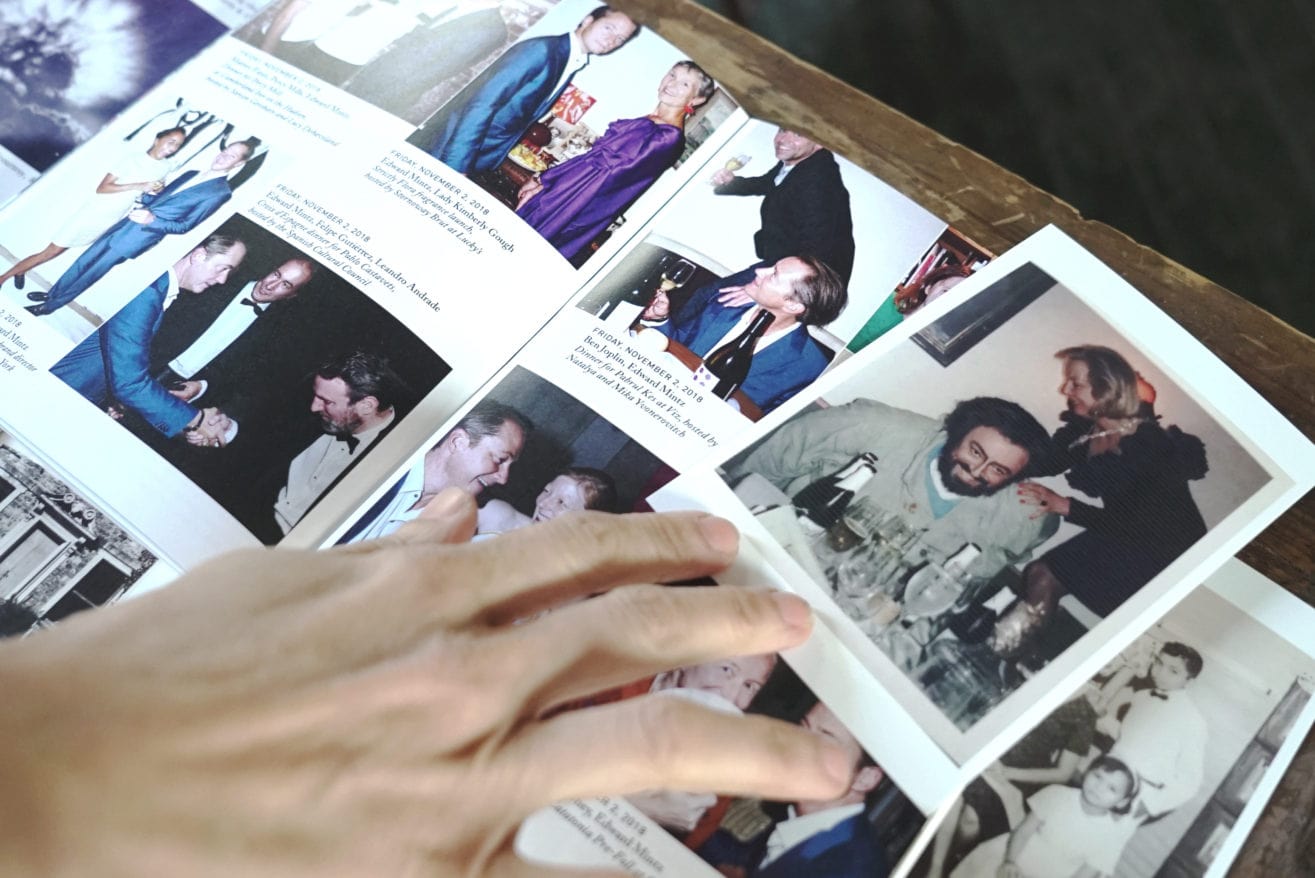

Shapton: For A Geist, for example, I was interested in how much currency the party picture has. Society pictures, by photographers like Patrick McMullan and Billy Farrell, have become ubiquitous. The photo op, the proof that someone was at the party—they’re basically visual name-drops, and it’s something that we all recognize. So much of the book is about being a guest or a host, about being invited or not invited, so I wanted to play with the idea of the guest and its etymological relationship to the word ghost, and have a guest at a party be, in essence, a ghost. The main character, Edward Mintz, goes to 38 parties in one night; some of them are in London, others in L.A.—he’s everywhere.

I asked my friend Paul, who works across the hall from my studio, to play him. Then I asked all my friends to wear their finest and come to a few parties I held, where I gave them plenty to drink and some chips and dips. I had this book of party pictures from the ’50s to the ’80s that I used to prompt my actors. For this one, I showed them this picture of a woman climbing behind Luciano Pavarotti, and I asked this guy to climb behind Paul, so I could get that sense of what happens when you’re at a party and you have to pass someone in a banquette.

The parties people have these days—this pop-up thing, that launch thing—they are just the weirdest excuses to generate PR and content. This story came from the idea of what those pictures mean to us now, how tragic they can be, and how much weight they carry in terms of social inclusion and exclusion.

Wang: Instagram has shifted the dynamics of party pictures. In the early days, there was one person taking a series of photos, in which you could be included or not. But now everyone is their own photographer. You don’t go to that one place anymore where you find all party photos. Instead, you go to different social media accounts.

Shapton: We’re all buying into this idea that these photographs mean something, when really they might not. In them we’re smiling, and it looks like a fun night, but what if that was actually the worst night of someone’s life? When we post, we’re usually alone. We want a hit of feeling, we want likes, but—and I speak for myself—I’m usually in a lonely place when I post a photo.

3. “The half-story you get forces your imagination to fill in the blanks.”

Wang: Does a project usually start from a visual point for you?

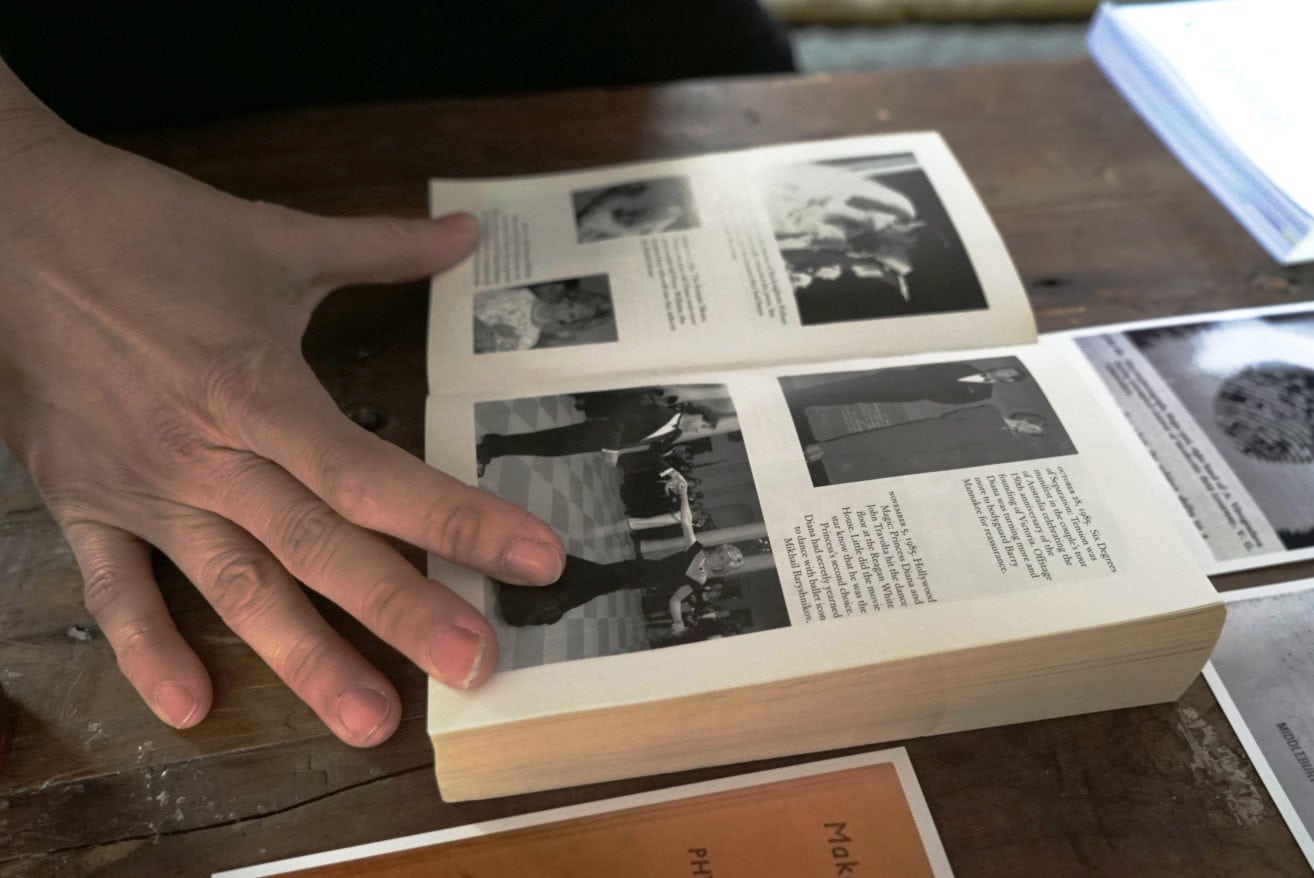

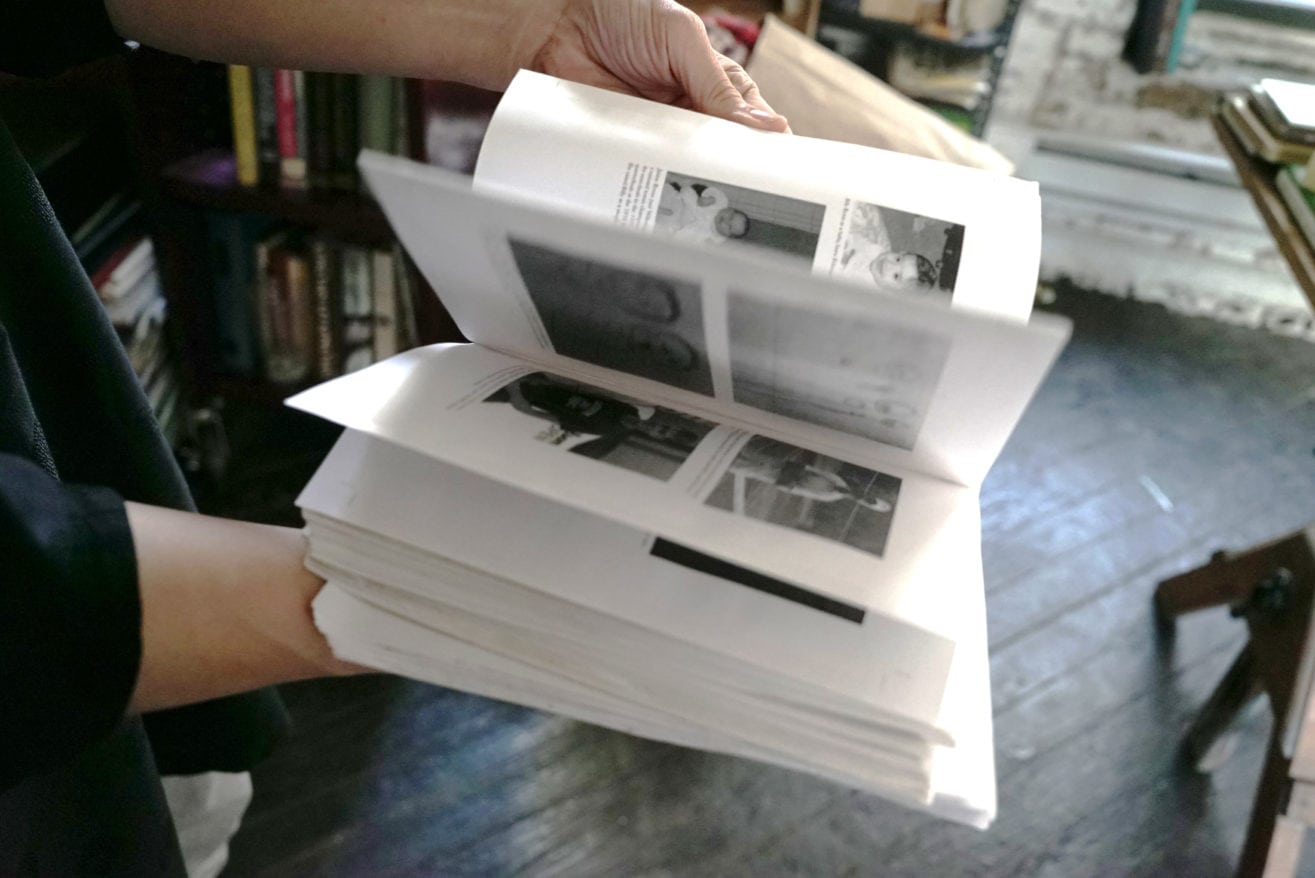

Shapton: Yes. The idea of this book came from things like…let me find it…like for example this Tina Brown biography of Diana, these pages of images. I asked myself, can I sustain that for 350 pages? This has a certain non-design design inflection we all understand. When I pick up a book like this, for example at an airport, I go straight to this part with the photos. The half-story you get forces your imagination to fill in the blanks, and I love that. The information is random, and I love that “gap-iness”.

So I started to write a story and place pictures, and I realized I had to break it up into a bunch of different stories. As I took my time—I had a daughter, I went through a divorce—I realized that I was writing ghost stories visually, and using these images to tell the story. It was so fun to work with Claire Vaccaro at Penguin. We had fun making the awkward, badly designed page. I would bring her stuff like this and go, “See how ugly this is? That is exactly what I want!”

4. “We pass judgment on clothing all the time, and it’s that passing judgment I’m relying on.”

Wang: You’ve included a lot of objects in your books, and clothes make up a particularly big part of that. What is it about clothes that attracts you?

Shapton: I contemplated buying this green dress but didn’t. There was this ghost of me in that dress that I had already conjured and filled in. But it was 200 dollars, and I hate spending over 100 dollars on a used thing. There’s a little fantasy you project on a dress. Again, there’s a gap between how we look at this and what it actually is. With clothes in particular, our imagination is so quick, in the way we can say that something is “not me” or “not you.” We pass judgment on clothing all the time, and it’s that passing judgment I’m relying on. I actually think clothes are even more poignant when you see them on a dressmaker’s dummy. Uninhabited clothes are a very powerful container, because we all have this collective knowledge of what it’s like to put on a sweater and button it up, to pull on a pair of pants, to pull on a pair of gloves. I love playing with implied or imagined collective knowledge.

Wang: This reminds me of Roland Barthes’s description of fashion as a language; each element of a garment is a marker of meaning. I think about that when I’m shopping online. The amount of things I see far surpasses the things I actually buy. But the pleasure is already gained by seeing it and fantasizing about it. So I call them my theoretical clothes; they don’t need to exist beyond that.

Shapton: Heidi Julavits in Women in Clothes said that “you dress for a future you.” I do think that when you imagine yourself in something you don’t own, there’s this little spirit that you create.

5. “We wanted to get right to the source of why people wore what they wore, to stories about their mothers and sisters.”

Wang: In designing Women in Clothes, you both sidestepped fashion industry conventions and played into them. In one photo series, Zosia Mamet is reenacting poses from fashion magazine shoots, but she’s wearing a black leotard—instead of something glamorous—and standing against a white backdrop.

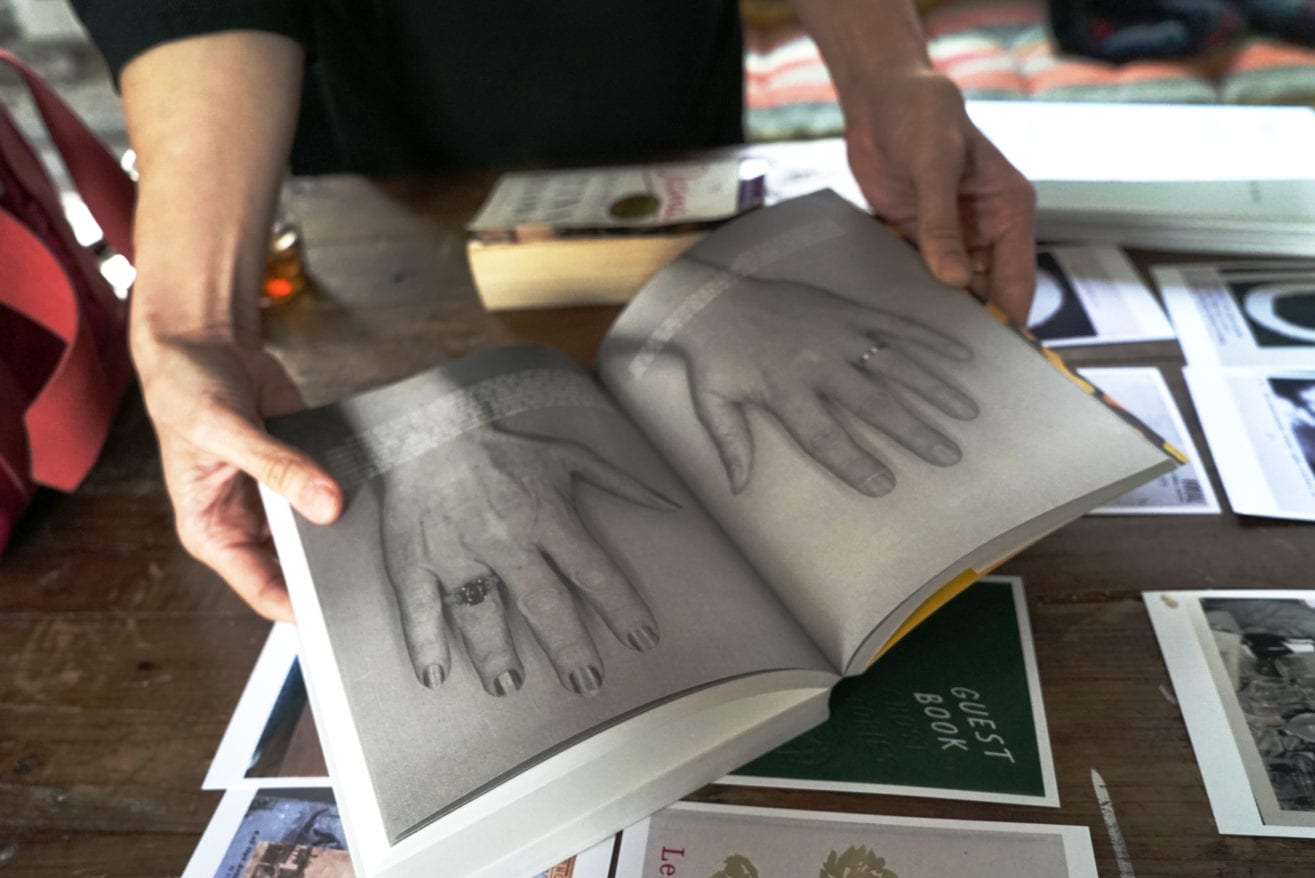

Shapton: We didn’t have fashion editorial budgets at our disposal, and we didn’t want to frame stories anything like what would published in a fashion magazine. We wanted to get right to the source of why people wore what they wore, to stories about their mothers and sisters. I designed the book to be quite informational, not aspirational. There are all these collections, like ones of stains, or these photocopies of hands. With Zosia, I tried to distill the language of the poses a woman’s body makes on those covers. It was interesting to read it without the layers of clothing and fashion photography, to watch Zosia, with her beautiful, not model-thin body in a body suit, do all these contortions.

Wang: It reminds me of how arbitrary certain fashion conventions are. When I worked at a fashion magazine, we seemed to make up these monikers behind our computers, and those would be sent out into the world and interpreted as fashion fact. We’d always call things “haute” or “outré.” It was a lazy habit, but it would be accepted by the world.

Shapton: Yes, fashion magazines are arbiters of arbitrariness. None of us really came from fashion backgrounds, so it would have been really weird for us to do anything “haute” or “outré.”

Wang: I think it’s pretty weird for anyone to do something “haute” or “outré.”

Shapton: We also didn’t want to alienate anyone who loved fashion or worked in fashion. I met the former editor of British Vogue, Alexandra Schulman, in London at a book thing, and she said she loved the book. That meant a lot to me, that a Condé Nast editor had read it and gotten it.

6. “As a swimmer, I was trained to do things over and over again.”

6. “As a swimmer, I was trained to do things over and over again.”

Wang: In Swimming Studies, you talk about how at some point, you realized you’re a good swimmer. When did you realize you’re good with working with images and text?

Shapton: Probably when I got jobs as art director, when I was trusted, when my opinion mattered, and when I realized I could make something that looked clunky look better. And along the way, you start winning awards here and there, and you take risks. It’s also about trusting your eye, and I know what I love to look at. My dad was an industrial designer, so I grew up with an appreciation for the nuances of design—I remember learning about serif and sans serif when I was six. I’m sure people in the profession thought that the type of design I was doing was very crude, so it’s also about finding your audience and your peers. With Guestbook, I relied on not-so-great graphic design. Instead, I used very popular, commercial layouts, because I wanted the pages to resemble books that were printed at a certain cost.

Wang: Do you have rituals in your work, and are they different for the visual and the writing sides of your work?

Shapton: It all involves repetition. Visually, I’ll do something over and over again to get it right. With writing, I’ll write it crudely first, and then pare back, and edit and edit again. And often, I return to the crude one. It all goes back to how you’re trained, which is what I try to get at in Swimming Studies. As a swimmer, I was trained to do things over and over again.

Wang: It’s a hopeful attitude, because it implies that if you’re not good now, it’s just because you haven’t repeated the process often enough.

Shapton: When I was depressed for the first time, in 2003, I did Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. My therapist gave me these worksheets, which are a big part of CBT. And I asked, “How many of these do I have to do before I feel better?” He said, “One hundred.” I thought, great, I can do that. I wrote about that in Swimming Studies. CBT is training—it believes that you can be trained and strengthened through practice. It’s a healthy relationship to repetition.

In On Directing, David Mamet talks about Stanislavsky, about how he wrote that “the difficult will become easy and the easy habitual, so that the habitual may become beautiful.” Also, apparently Stanley Kubrick had actors draw circles really quickly and have them try to make the ends meet up. He would have them do that over and over again, and that has to do with physically wanting to get something right. All that repetition will serve you as a thinker and an artist. Your mind has to be in shape to be able to recognize a moment of inspiration, and that practice keeps it in shape.

7. “I find InDesign, or even my email, a more natural place to write.”

Wang: How do you put the visual and textual parts together?

Shapton: This is an early draft of the book, a working dummy. I always do this, make a fake version of the book. I keep getting alerts on my computer about how my memory space is low, because I have so many images and layouts on it—version one, two, three. Making layouts is how I write. InDesign is huge for me—thank you Adobe! It’s interesting how crap I am in editing in Word. I find InDesign, or even my email, a more natural place to write. With Word, I’m still figuring out how it works—when people leave comments, I get so lost.

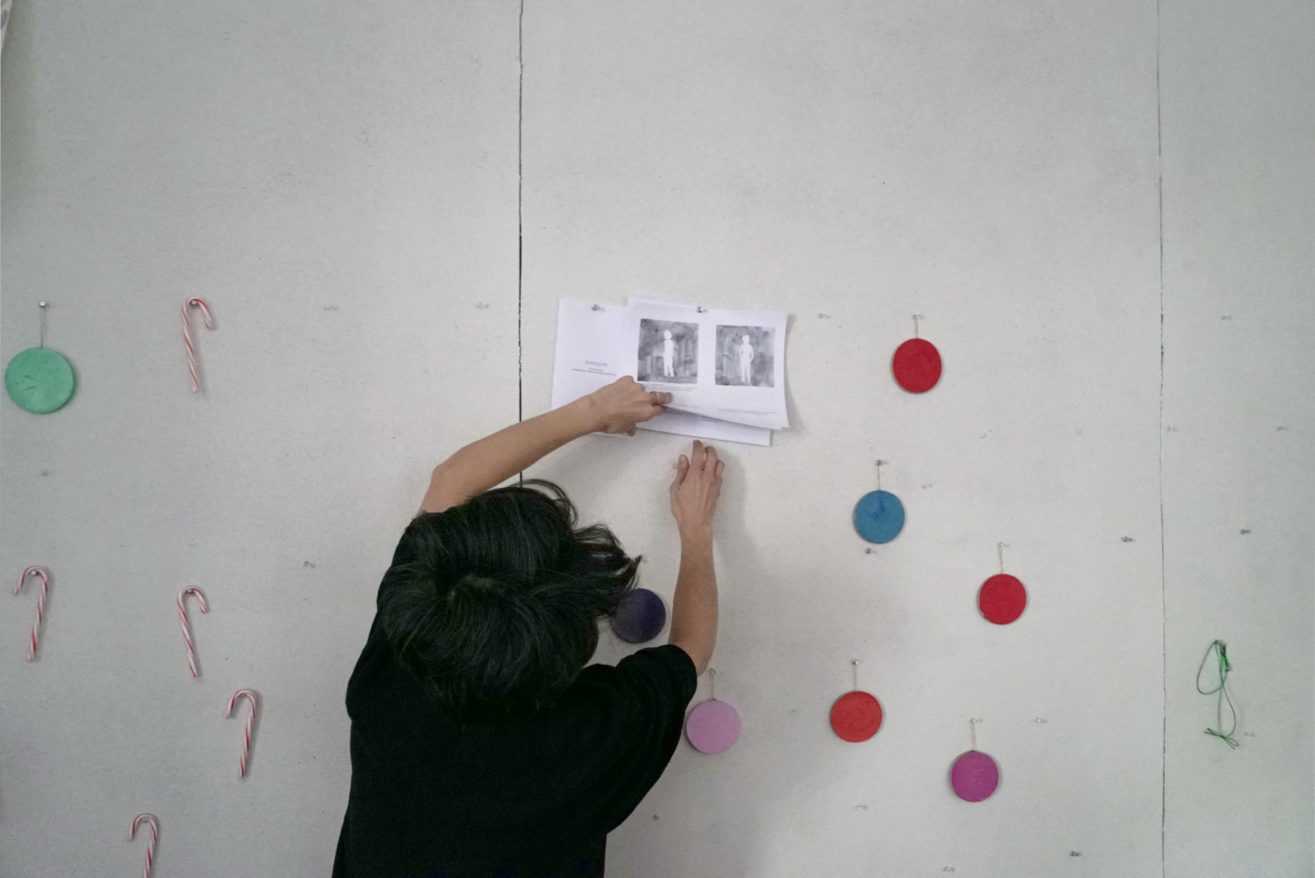

Wang: Do you often pin up things over there?

Shapton: Heidi Julavits works over there. And yes, I often pin up stuff in progress. I always have to lay them out, because my books are so layout-intensive. I used to have my whole book on that wall over there, and I took that all down for our Christmas party.

8. “I like a little bit of minimalism in all the work I appreciate.”

Wang: I want to talk about the role of absence in your work. Where does your attraction to gaps come from?

Shapton: It comes from the sort of stories I like to read. Alice Munro is the master of not filling in everything. I like a little bit of minimalism in all the work I appreciate. Maybe it comes from sports too, from this idea of efficiency: How can you spend the least amount of energy to go the furthest and fastest? That influences how I write and design, where I always try to get the point across with as few words as possible, with as little information as possible. In some ways, it’s a preference, but in other ways, it’s a form of respect, where I trust my readers to meet me halfway. I love cutting words—I keep going back to that feeling of me in the water, of using as little energy as possible, as streamlined as possible, thinking, “I have to be in this pool for two hours straight and not throw up at the end.” I want to master the direction of absences, like so many artists I admire do.

Wang: Can you give an example?

Shapton: I love Jaws. [Steven Spielberg] managed to make that movie work without us seeing the shark that much. That was also a practical choice, because the shark didn’t look that good. I also love Ellsworth Kelley. I’m in awe of some of the drawings and prints he made. That said, I also really love a good Romantic painting. I love Lydia Davis too; her micro-fiction really speaks to me.

Wang: So you’re more attracted to short-form than long?

Shapton: Probably. That’s funny, because one of my favorite books is The Loser by Thomas Bernhard, which has no paragraph breaks. That said, the narrator remains unnamed, and there’s a huge minimalism to it. There are things he leaves out—he doesn’t ever describe a place or a room in the whole book.

I don’t have that much experience doing long-form myself. The longest piece I’ve done was probably this 2016 piece about the Franklin expedition, a Victorian naval expedition, but I broke that up into parts. I’m always weaving and layering, and giving the reader small stories.

Wang: It’s one of those tricks where you can tell yourself, I only have to make it to that part, and then that part, and that part.

Shapton: With swimming, I had to break up those miles and hours of training into chewable bites. And then you go on to the next thing. In my mind, everything is survivable when it’s chopped down into small pieces. We all have a natural need to limit our apprehension to what’s put in front of us. So much of design is breaking up the grayness of black type. You need to put in a pull quote, an image, or a break, so the reader isn’t daunted. But then with Bernhard, his pages are all gray, without paragraph breaks. There’s beauty in both.