Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

In a 1990 interview, Toni Morrison pointed to the dangers of the so-called “master narrative.” Morrison defined it as “whatever ideological script that is being imposed by the people in authority on everybody else,” and identified wide evidence of its damages: from a little girl who believes the most prized Christmas gift she can get is a white doll; to Ella, a character in Morrison’s Beloved, who has learned to “don’t love nuthin.’” Nearly three decades later, the writer Jabari Asim is wrestling with the same mainstream script. In his latest essay collection, We Can’t Breathe, he asks himself, “On any given day, how often do I manage to keep oppressive thinking out of my head? Am I ever free from an imagined white gaze?”

For Asim, writing is a way of beginning to answer those questions, and narrative a mode of resistance. His decades-long career exemplifies this, from his work as an editor for publications including The Washington Post and NAACP’s official magazine The Crisis, to his role as MFA program director at Emerson College, to own writing across fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and children’s literature. His 2008 book The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn’t, and Why, a thorough interrogation of the life of the titular word, shows Asim’s commitment to uncovering the destructive narratives embedded in American myths, whether in the writings of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson or contemporary hip-hop. Essays in We Can’t Breathe are similarly ambitious: A simple point of departure—an African American’s strut—expands into a history of jazz, Southern planters’ efforts to push back the Great Migration, and the dangers of moving around in a black body, as the writer himself does every day.

Asim and I spoke about how words can be used as weapons, how he prepares his students for a punishing publishing landscape, and how he situates himself in a long tradition of African American writers: “like entering a room when a conversation is already taking place.”

1. “I’m very aware of stories as instruments of power.”

Mary Wang: What do we see here?

Jabari Asim: There’s a really wonderful walking trail near my house called the Emerald Necklace, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who also designed Central Park. If I don’t have to head to campus straight away, I’ll walk there for an hour or so, and I’ll think of whatever book I’m working on. That habit comes from my first job, when I was a newspaper writer. Once it was determined what I was going to write about, I would leave the office and take a walk. I would meditate on the piece, and the lead of the piece would come to me while walking.

When I see that tree, I also think about these lines from a short story by Amiri Baraka:

“We can think and be quiet and love the silence.

We need to look at trees more closely.

We need to listen.”

Mary Wang: In another interview, you said you often share this Muriel Rukeyeser quote with your students: “The world is not made of atoms, but it’s made of stories.” In your work, you put a particular emphasis on the narratives that shape our lives. To you, stories contain more power than the tales that we tell to entertain and pass time.

Jabari Asim: When I set out to write a story, I want it to be entertaining first. If it happens to be instructive or informative in some other way, I’m very pleased. If you don’t hold the reader’s attention from the beginning, it’s going to be very difficult to convey a message.

At the same time, I’m very aware of stories as instruments of power. As a member of an oppressed minority, I can’t help but to be sensitive to that. So I think a lot about narrative capital, and the value and power of storytelling. It always reflects back to my origins growing up in St. Louis, where I was surrounded by storytellers. They told their stories to say, “I’m here, I’m present on the earth,” but also to indulge in joy and please one another. We tend not to think of those stories as sources of power or value, but narrative can be a form of resistance.

Mary Wang: In We Can’t Breathe, you talk about dismantling the “master narrative” and plead for a “constructive black contrarianism.” How does that translate to decisions you make on a language level?

Jabari Asim: The language has to be chosen very carefully. In these contexts, we can think of words as weapons. The great African American painter Charles White said that, for him, paint was the only weapon. The great photographer Gordon Parks’s memoir was called A Choice of Weapons, and photography was his weapon. So in some respects I’m thinking of weaponized language. It’s deliberate, it has to have style, but it has to be carefully applied. Each word should strike the reader in some meaningful—and possibly transformative—way.

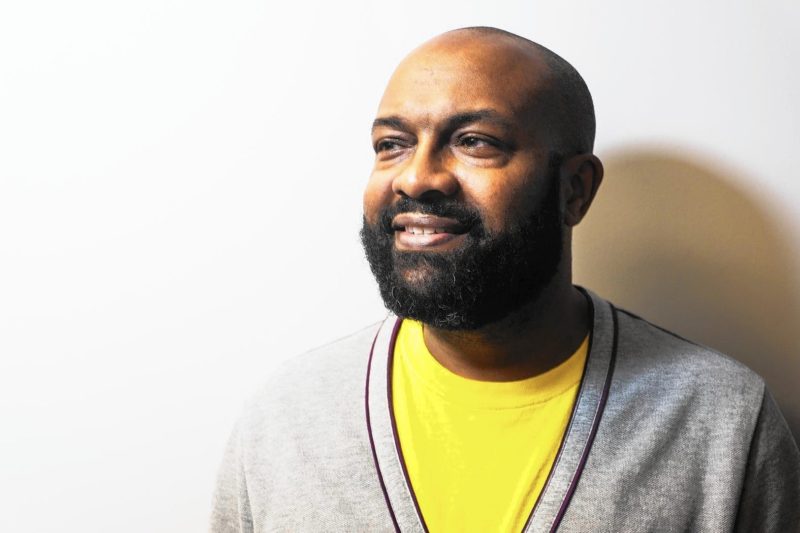

2. “They were taught the systematic dehumanization of black people from the very beginning.”

Mary Wang: This image features a weapon, and what we see here has the ability inflict different kinds of harm. The credit at the bottom shows that the image was featured on a website called iFunny. That might be the most painful part of the photograph, because it contextualizes it in the present.

Jabari Asim: In The N Word, I write about a game called “Chopped Up Niggers,” a puzzle made up of disassembled black bodies. In my writing, I try to draw connections through certain cultural practices, and one of the practices of majority culture is to make fun of black death, black suffering, and the mutilation of the black body. These were toys made for children, who were taught the systematic dehumanization of black people from the very beginning.

I was looking at this image while I was writing “Shooting Negroes,” which appears in We Can’t Breathe. One thing I write about in that piece is the comic responses to Trayvon Martin’s death: It became a phenomenon for white fraternity boys to stretch out on the ground with spilled Skittles and pretend they were Trayvon Martin. Each time these atrocities happen, I remind myself that there’s a precedent, and that it’s been domesticated in many ways. These practices were made into family entertainment.

Mary Wang: Just as there’s a tradition of dehumanizing black lives, there’s a tradition you operate in, where marginalized writers take the language of white institutions and turn it on its head.

Jabari Asim: For me, this tradition goes back to a few early African American writers. One was David Walker, who published his appeal in 1829, and later, Frederick Douglass. Both men carefully chose the language of the Hebrew bible, the Old Testament, to accuse and challenge those who oppressed black people, because that same language was used to justify the enslavement of Africans.

“Getting it Twisted” [in We Can’t Breathe] talks about the value of turning that language on its head. For example, Newt Gingrich mounted a deliberate linguistic campaign to demean and discredit the left some years ago, and I suggest that we use the same language to challenge the right. On the left there’s a timidity around language, like when mainstream newspapers embrace terms such as “alt-right” and “white nationalists.” Those same newspapers had to be taught not to use words like “illegal alien.” Though racism is accepted in the US as a custom, it is illegal by law. So why are we calling them “alt-right” and not “illegal racists”?

Mary Wang: In We Can’t Breathe, you bookend your own work between quotes by other African American writers, as if your texts exist within larger histories.

Jabari Asim: I sure hope that that’s what’s happening—I cannot envision my journey as a writer without it. It’s like entering a room when a conversation is already taking place. I want to be a part of that conversation, and that conversation is strengthened when we see it as a continuum. There really aren’t a lot of new ideas—there are mostly variations on ideas that have been around for a long time. So part of what I’m doing is acknowledging that I’m aware of the tradition I’m entering, and trying to enter it with respect.

Mary Wang: In the same book, you switch between the singular “I” and the collective “we.” The first comes into play with childhood anecdotes, while the latter might stand for African Americans or black culture in general. How can we productively switch between the specific and the generic?

Jabari Asim: When I use the “we,” I try to acknowledge that African Americans are complex and exist in multitudes. We can say “the black community,” but what we really mean is black communities, plural. We are oppressed and brutalized in the same ways. The differences emerge from how we respond and how that looks in terms of history. A descendant of enslaved ancestors might have differences from someone like Barack Obama. His history is no less valid, no less legitimate. The challenge of the writer is to reach those multiple audiences with respect.

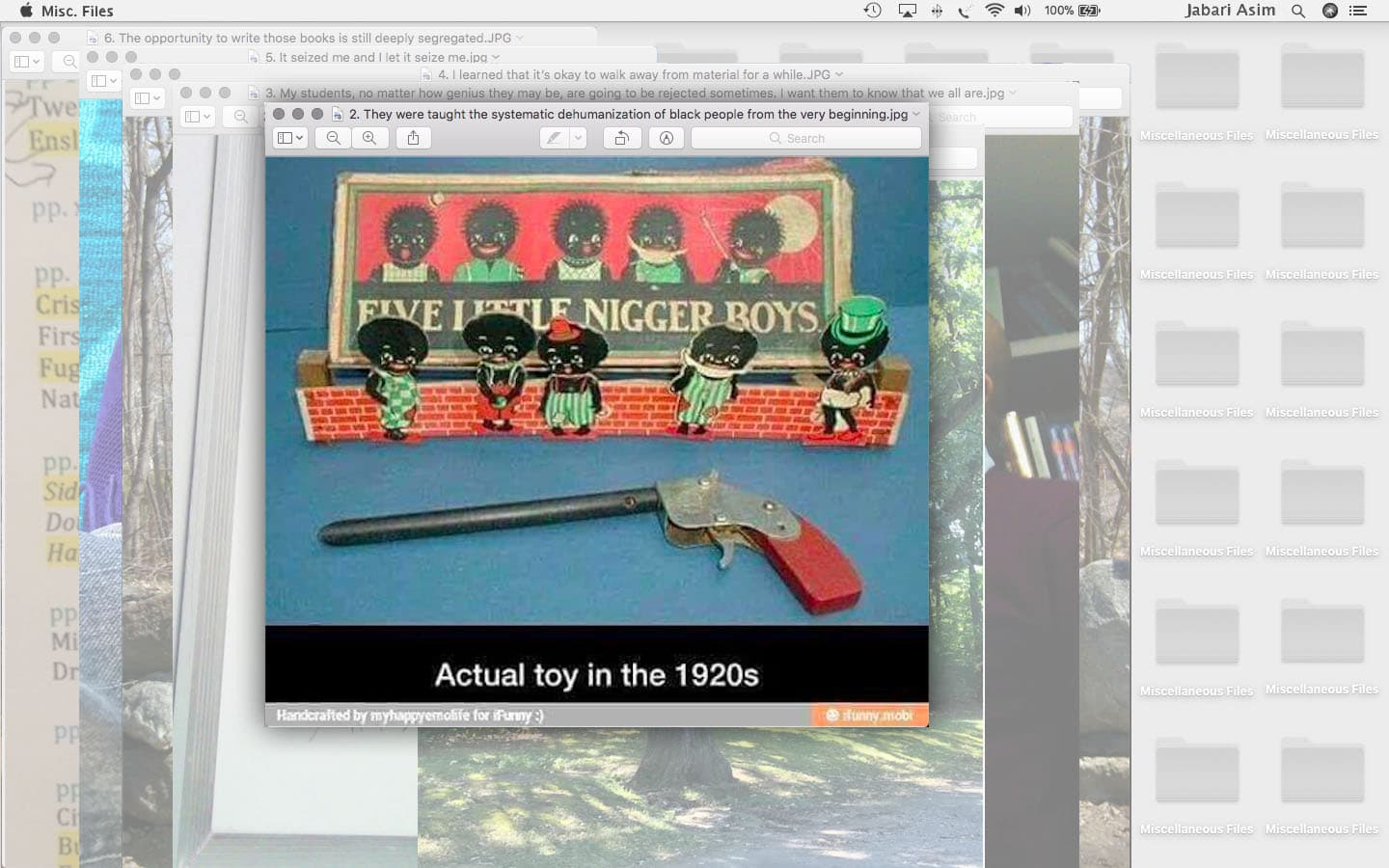

3. “My students, no matter how genius they may be, are going to be rejected sometimes. I want them to know that we all are.”

Jabari Asim: This is the outline of a novel in progress. I was outlining my novel in my office on campus, while outlining my non-fiction project in my office at home. I’m doing it on campus because I want to show my students how it works for me. I share a lot with them, from proposals—successful and unsuccessful—to notes from various editors, just so they can see how the process works. One of the points I make is that everybody needs an editor. I’ll show them a passage that I thought was the most brilliant thing I had ever written, and it turned out it wasn’t.

Mary Wang: I’m amazed that you share so much with your students. During my MFA days, I rarely saw a professor who was willing to give us a peek into their human vulnerability.

Jabari Asim: When I first got to Emerson, I read an article about one of my colleagues, who taught television writing. One of the things he showed his students was a pilot he’d shot that wasn’t picked up, instead of something else he was known and celebrated for. I thought that was very instructive for the students, who were possibly quite dazzled by him. My students, no matter how genius they may be, are going to be rejected sometimes. I want them to know that we all are. And we’re still standing and writing.

Mary Wang: You’ve been an advocate for writers of color since the start of your career. In the ‘80s, you co-founded Eyeball, a literary magazine and reading series that featured Tracy K. Smith, Paul Beatty, and John Keene, among others. And you’ve shown the same commitment during your time at The Crisis and The Washington Post. Have you noticed a change in how writers of color fare in the American publishing landscape?

Jabari Asim: No. The American publishing landscape is terrible. It’s abominable and racist and fundamentally dishonest. Publishers say that they’re making an effort to be more diverse, but I see very little evidence of that. The bookshelves are groaning under the weight of mediocre works by white writers, and I just don’t believe there aren’t more writers of color who are writing books that are just as good. Publishing is all about money—the other explanations are a smokescreen.

Mary Wang: So how do you prepare students for that landscape? MFA students of any background face the tremendous challenge of investing time and money into something that doesn’t guarantee them any success.

Jabari Asim: First of all, I tell them the truth. I also tell them that I didn’t choose to be a writer—writing chose me. And that you should only write because you can’t help it. If you go into it for any other reason, you probably should find something else to do. But if you’re obsessed with it in a constructive way, you should know the landscape you’re entering into.

Mary Wang: Is it because of this landscape that you told your publishers not to put a black face on the cover of your novel, Only The Strong?

Jabari Asim: A Taste of Honey has a beautiful picture of a black family on the cover, but some might see that as a sign that the book is not for them. I’ve had a number of experiences like that, with my children’s books in particular, which have images of children of color on the cover. At book fairs, I’ve seen white families back away from those books as if they’re kryptonite. So I wanted to experiment and not announce visually that the book is about black people. As people begin to read, it will be obvious, and they can respond however they see fit.

Mary Wang: Has that experiment paid off for you?

Jabari Asim: I don’t know. But I would be willing to do it again.

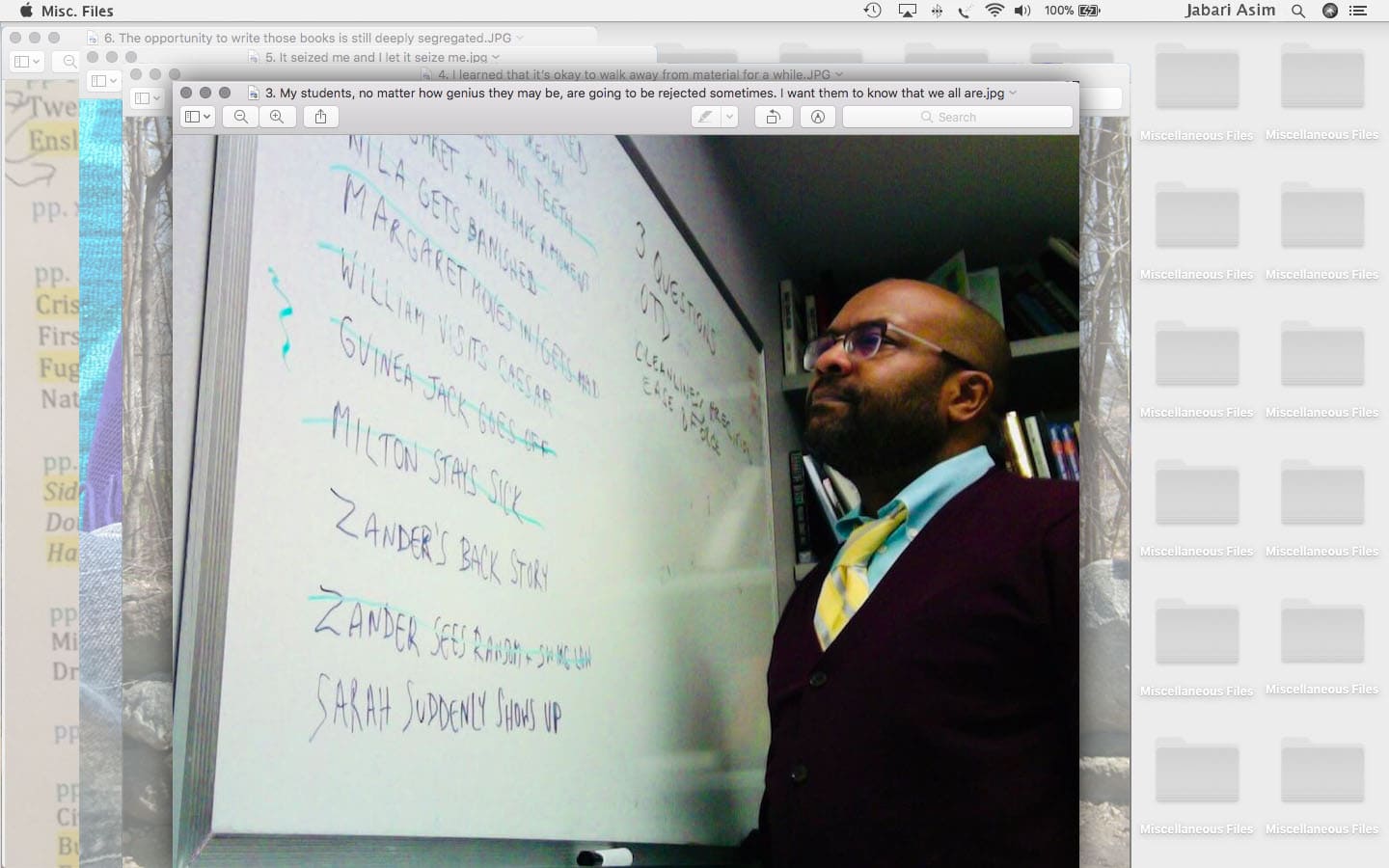

4. “I learned that it’s okay to walk away from material for a while.”

Jabari Asim: This is from “Brick Relics” in We Can’t Breathe, which emerged when my wife and I drove past this marker that said “The Slave Wall.” I Googled it when I got home and found out that an enslaved man called Pomp had built the wall. The theme of walls became the animating engine for the essay, in which I wanted to connect different ideas about walls, construction, enslaved people building things and leaving them behind, and how they were acknowledged, or not. One of the questions I asked is, “If we know the name of the man who built this wall, why is it called ‘The Slave Wall’ and not Pomp’s wall?”

I thought about how Michelle Obama said that slaves built the White House, and I remembered seeing journalists racing to their computers to check whether that was true. And I saw the impulse to deny the contributions that African Americans made to the physical infrastructure of the United States, while there were attempts to remember Confederates through statues and monuments.

Mary Wang: You have to confront a lot of racist material in researching and writing your work. What is that like?

Jabari Asim: It’s pretty mentally challenging and painful. It helps to have a family I can return to after working all day. Also, at the end of that process of writing The N Word, I started writing Taste Of Honey. The material was so different; it made me feel better about myself and life in general. I learned that it’s okay to walk away from material for a while if it’s challenging you too much. I tend to be a workaholic, but leaving the work on the table can actually have a positive affect.

5. “It seized me and I let it seize me.”

Jabari Asim: I tend to write in blue shoes. I also tend to use green pens. It started years ago, when I was looking at The New York Times’ Sunday fashion section, and I saw a picture of an African American gentleman in a beautiful suit and blue shoes. Those shoes were speaking to me. I have all kinds of blue shoes now. For me, they’re a natural anti-depressant—when I look at them I feel alive, creative, and vibrant. The green pens started many years ago, when I read that Langston Hughes used them. Green is actually my favorite color, so it was perfect.

Mary Wang: It sounds like these habits were developed at the start of your writing life. When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Jabari Asim: When I was in college, in a pre-law program at Northwestern University. I was a political science major, and Gwendolyn Brooks came to my school for a three-day residency. I skipped all my classes just to be wherever she was. I was transformed by the experience, and after she left, I told my parents that I wasn’t going to be a lawyer. I switched my major to English and started pestering some of the African American writers who were on the faculty, showing them my work. Northwestern is in the suburbs of Chicago, so I started catching the train into the city, to signings and readings where writers were going to be. And it changed my life. It seized me and I let it seize me. I returned the embrace.

Mary Wang: You made your first money in journalism. Was that because you were a political science major?

Jabari Asim: No, it was because I was desperate and poor! I was in St. Louis, and I was beginning to get poems published. I went to a gallery opening, where I met this sculptor and asked if I could interview him. He let me come to his studio, and I sold the article to a weekly newspaper for 35 dollars. I was like, “Ah man, this is nice! Let’s try to sell another one of these!”

Mary Wang: You were the deputy editor of The Washington Post’s Book World until 2007. As someone who studies the narratives that weave through our lives, how would you advise readers to engage with the news critically, especially now that journalism is so polarized?

Jabari Asim: As I write in We Can’t Breathe, part of oppression is about getting between the oppressed and their stories. So I’m mindful of who’s telling the story. I don’t believe that only African Americans can tell African American stories, but I do think we should regard stories with a healthy skepticism. And if we are within communities and we are writing those stories, we need to be mindful of all the distortions that are out there. If we have an opportunity to publish, we have an opportunity to disrupt whatever narrative is playing out about our particular group. It’s very complicated, because you want to disabuse white people of their misguided notions about your people, but at the same time, you have to answer to your people. They’re going to challenge you. That’s why I go to first-person sometimes, to say, “This is my experience, but it might be different for you.”

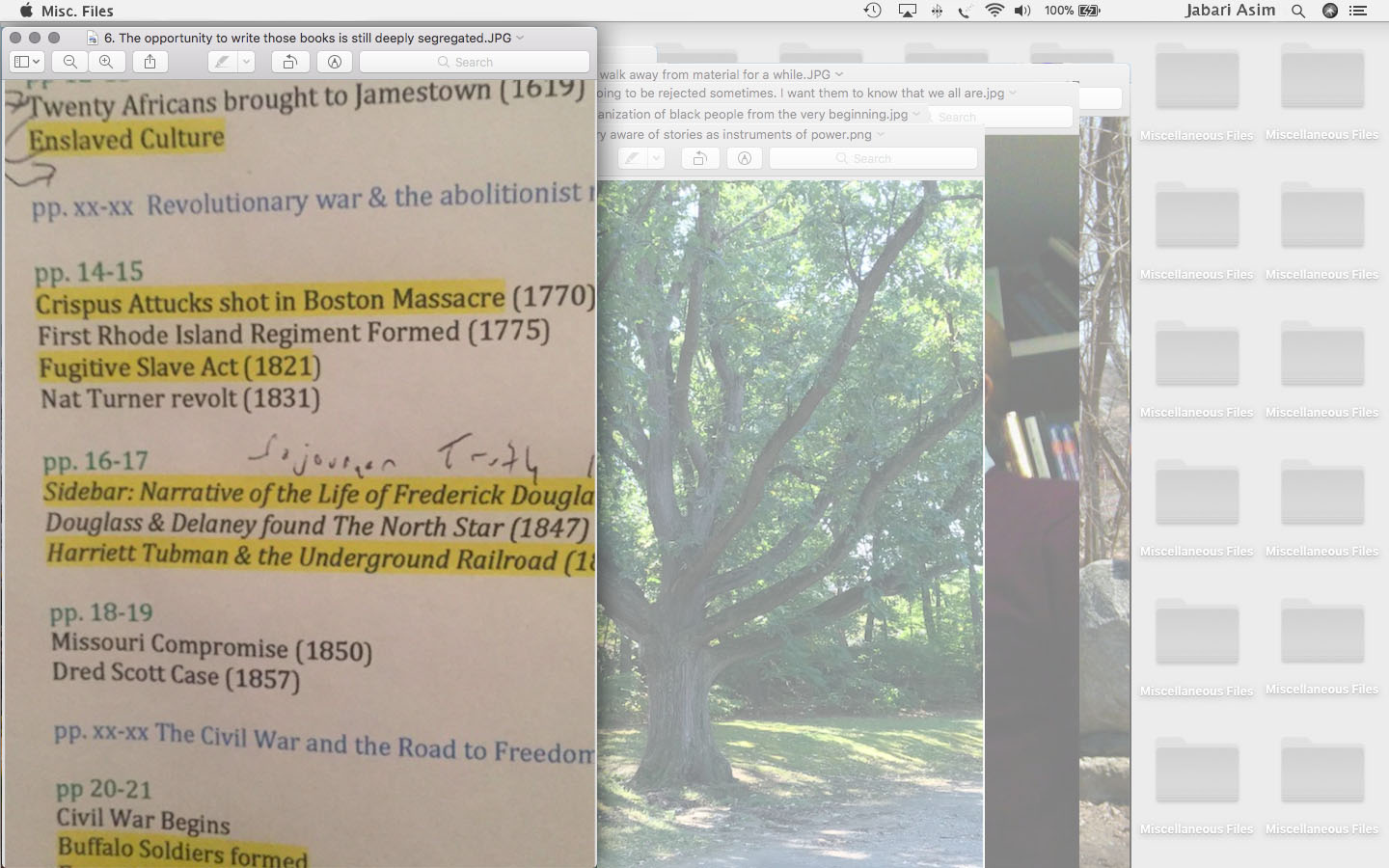

6. “The opportunity to write those books is still deeply segregated.”

Jabari Asim: For A Child’s Introduction to African American History, I created a timeline even before the outline. Now it sits in the back of the book, and you can pull it out. I write from the perspective of a husband—as someone who’s been married for 30 years—but also from the perspective of a father, as I have five children. Fatherhood is one of the few things that is more fulfilling than writing. I originally wrote children’s books to entertain my own children. We had so much fun at bedtime; we’d read stories, I’d make up stories, I’d make up nonsense rhymes, and they’d make up nonsense rhymes.

Mary Wang: How do you translate the ideas you wrestle with in your adult books into something suitable for children?

Jabari Asim: It’s about the narrative. Children—especially children of color—should be exposed to narratives that comfort them, uplift them, and enrich them. I don’t think that only writers of color can write those stories. But if you look at the developments in children’s book publishing, you’ll see there’s been an increase in picture books that feature children of color but there hasn’t been a commensurate increase in authors of color. So we’re seeing more books, but the opportunity to write those books is still deeply segregated. As a writer of color, I want to challenge that. I want to say: I am among the multitude of writers of color who can write for children. Don’t pretend we aren’t out here.