Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Though Valeria Luiselli has long been hailed a “writer’s writer,” looking through her “miscellaneous files” feels more akin to visiting the studio of a visual artist. This is not only because of the visual and tactile materials she often incorporates into the pages of her books, but because of the way she allows the properties of such raw material to inform the shape of the text. The plant the protagonist finds on a rooftop in Luiselli’s first novel, Faces in the Crowd, was the plant that lived on the author’s desk. Her second novel, The Story of My Teeth, grew out of Luiselli’s collaboration with a group of workers at a juice factory in Mexico City; from New York, she sent them installments of the story and then used the audio recordings of their discussions about them to shape the next step. The legal documents Luiselli collected as an interpreter for Central American child migrants form the backbone of Tell Me How It Ends, a book-length essay structured after the intake questionnaires child migrants receive from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

The same documentation on child migrants reappears in her latest novel, Lost Children Archive—along with additional photos, maps, and recordings that Luiselli collected on her travels before she started writing the book, and on those driven by it. Set during a period when America’s treatment of child migrants had—and has—become unconscionable, the book follows a family’s road trip from New York to the US-Mexico border after the parents “made the very common mistake of thinking that marriage was a mode of absolute commonality and a breaking down of all boundaries, instead of understanding it simply as a pact between two people willing to be the guardians of each other’s solitude.”

But the book is more than a story about a splintering marriage, or a young boy’s description of complex events in the language he shares with his sister, which form the two halves of the narrative. The quotes, references, and secondary material Luiselli weaves together and organizes into “boxes”–chapters containing the documentary material the family members collect–ensure that Lost Children is both “the book and an archive of the book,” as Luiselli told me. On Skype from her home in the Bronx, she and I talked about how each of her projects drive their own archival processes, how she writes in “intense dialogue with other books,” and how, having grown up in countries including South Korea, South Africa, and India, she built her own literary canon.

1. “The fiction was driving the documentation, like an inverse procedure.”

Mary Wang: You have a very distinct way of shaping raw material into books. An essay from your collection Sidewalks was published in The New York Times, and in turn made way for the female narrator in Faces. Tell Me and Lost Children revolve around the same road trip to the US-Mexico border. It’s as if your words exist as atoms that can morph into different forms at different times.

Valeria Luiselli: I usually collect a lot of material things—scraps, pieces, cutouts, and photos—while I write a book. The plant that was present in Faces was actually present in my life, on my desk. But I also create archives: with The Story of My Teeth, I asked the people I was collaborating with in Mexico City to look for a series of spaces I had found online and wanted to appear in the novel: a cafeteria, a karaoke bar, a dentist’s office, etc. They sent back pictures, and an archive was created for the purpose of this fictional/non-fictional part of the book. I also made a map of swings in Harlem for Visual Editions, a publisher in the UK. This was some years ago, when my daughter was still really young, so I needed to find something I could integrate her into, because I was taking care of her most of the time. So the project became about looking for every single swing for kids in Harlem parks and taking pictures of those. While she was swinging, I was able to make notes about motherhood, parks, migraines, and interactions with adults and dogs.

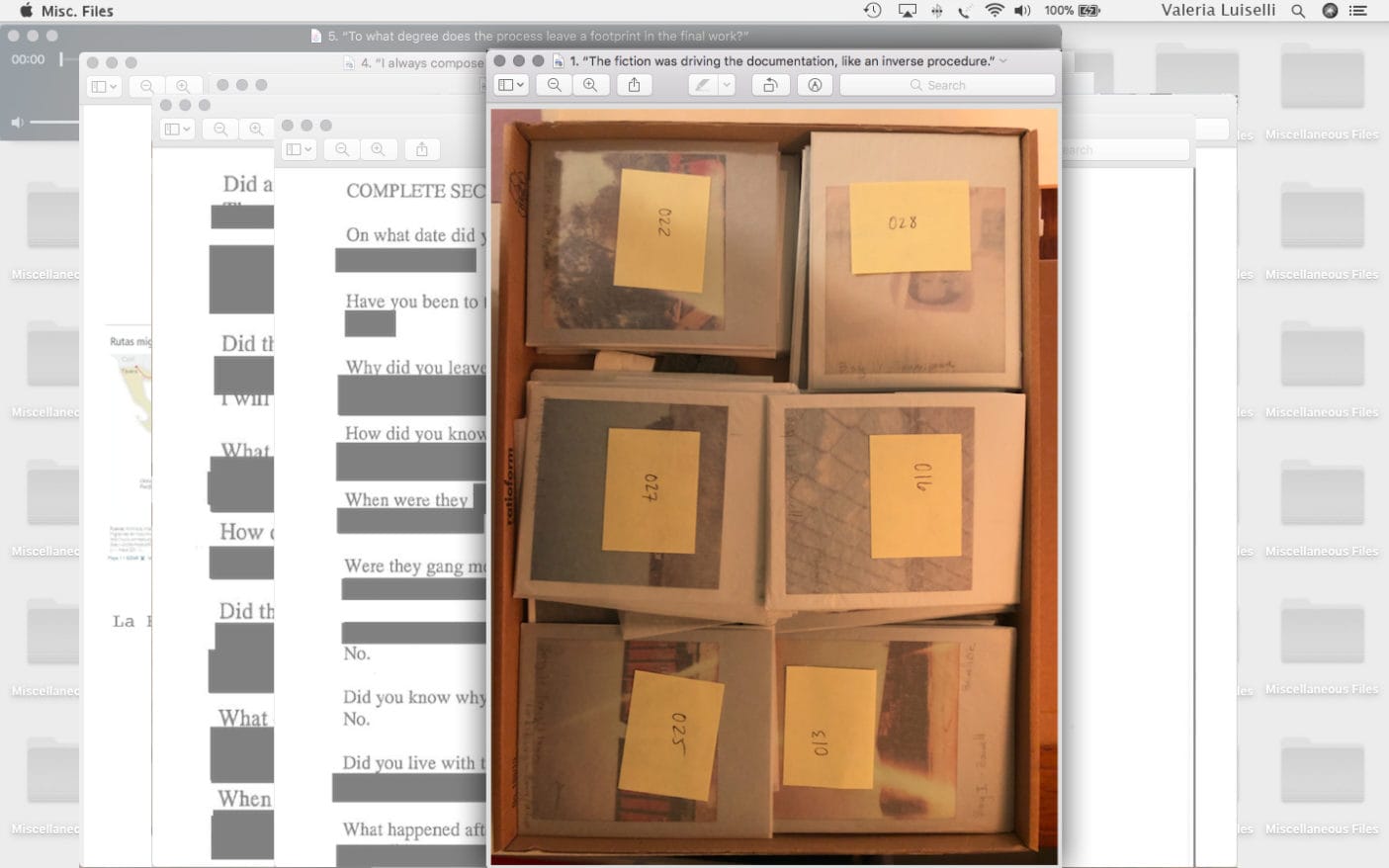

With Lost Children, the collection process went overboard. I have seven boxes in which I recreated the archive of the family in the book, because I wanted to have it materially present. I also created the photographic archive for it: the pictures in the novel were pictures I took traveling through the US some years ago. But then I went on other trips and photographed for the purpose of the novel. I wasn’t using photos to illustrate something—the fiction was driving the documentation, like an inverse procedure.

It’s important for me that each book drives its own archival process. I carry certain understandings from one book to the other, but I usually do not repeat procedures, because I allow a book to grow amorphously first, through notes and pieces, which then starts dictating what procedures I have to use to make a form.

2. “There are always fingerprints of the archive in my books.”

Mary Wang: There are certain overlaps between Lost Children and Tell Me: they both allude to a family’s road trip to the US-Mexican border—whether it’s your own or that of the fictional characters—and they both address the plight of child migrants. Yet the approach and the final results are so different. One is a condensed, relatively linear essay, the other is a sprawling novel told from several points of view.

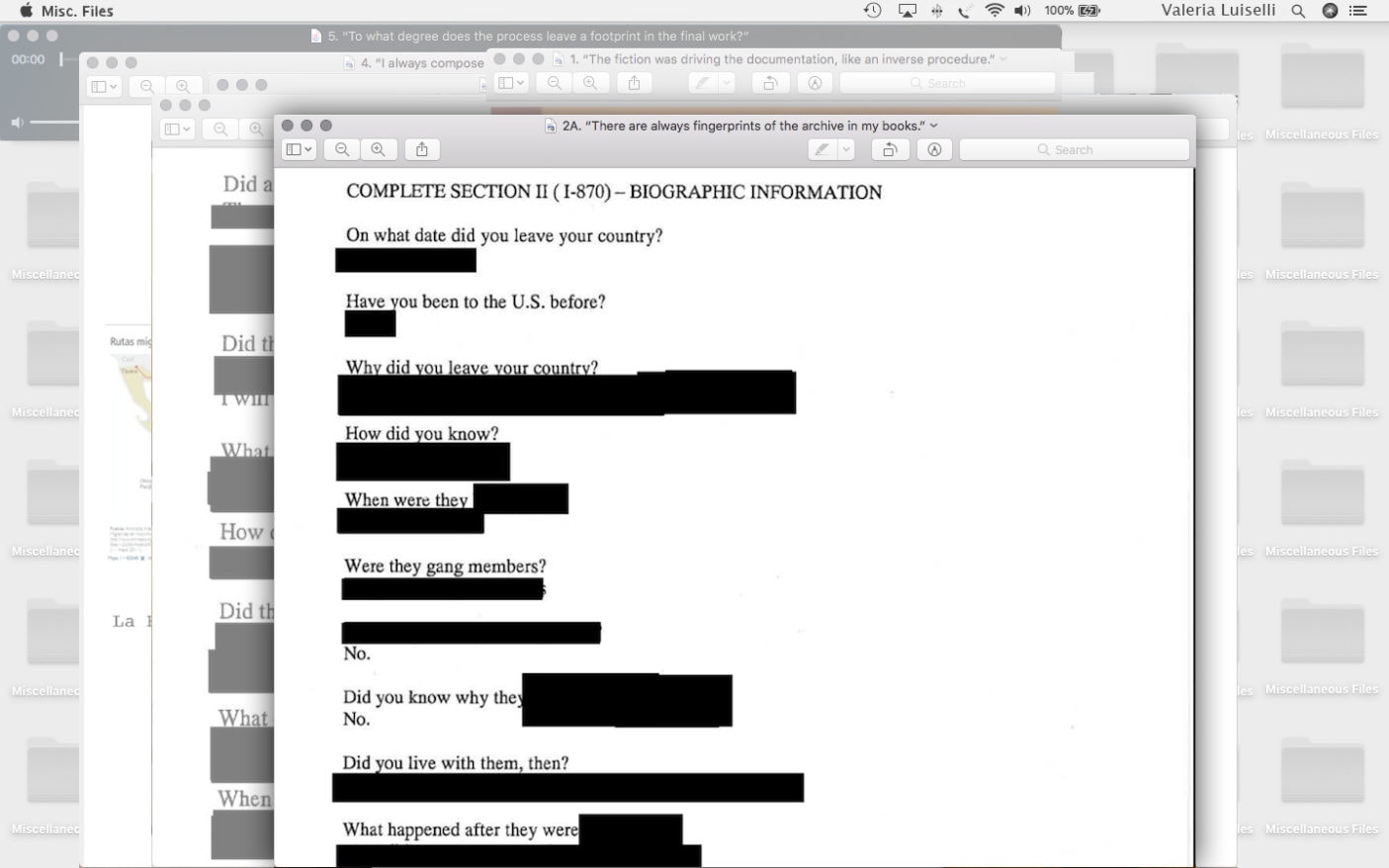

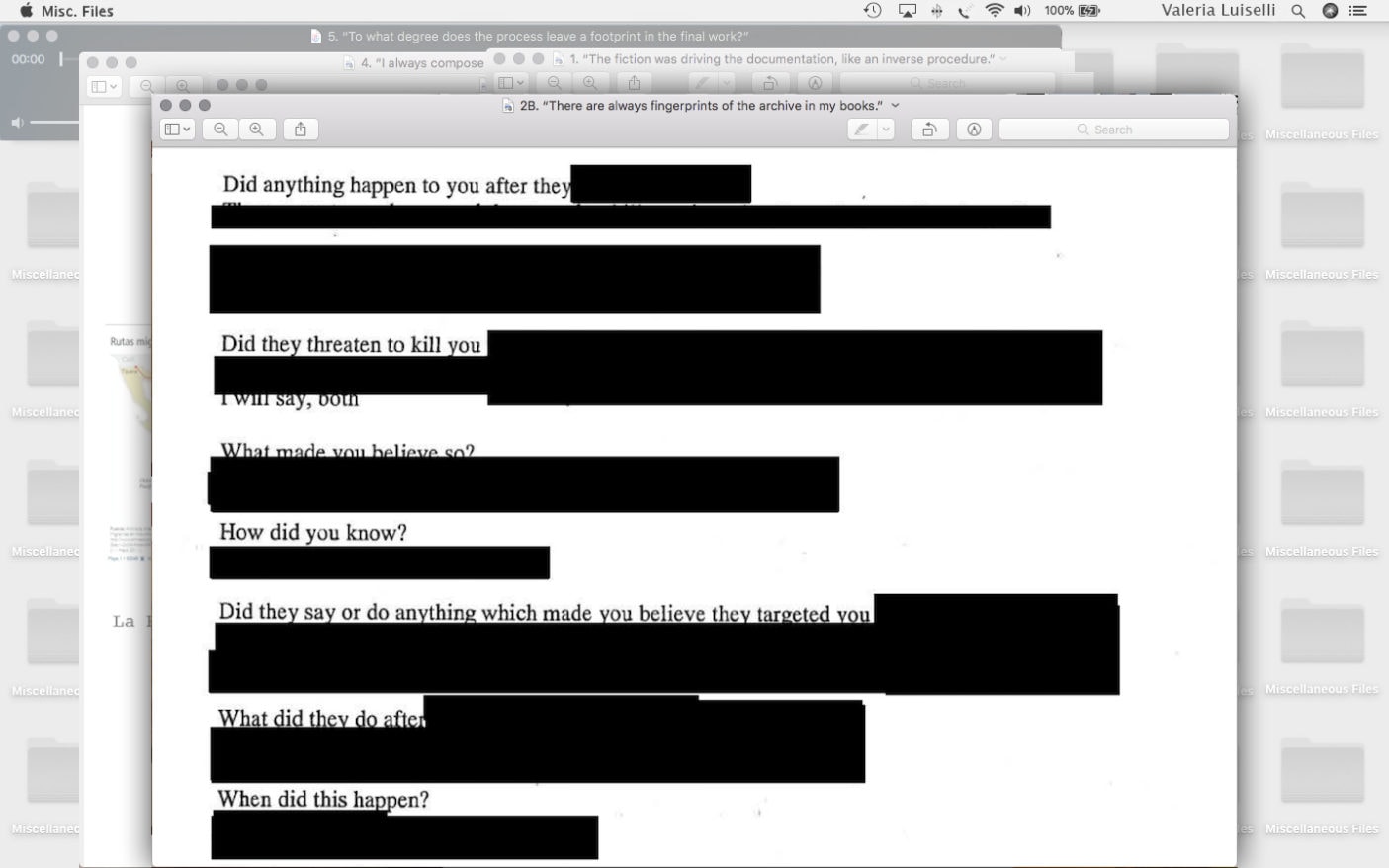

Valeria Luiselli: I had been putting together a collection of documents to study for my work in court as an interpreter, from explanations of immigration law to the different questions that are used in court, such as the “credible fear” interview. In court and in detention centers, people who volunteer for different positions conduct interviews that either prepare a person for an asylum interview or a credible fear interview, or conduct interviews that, as it was in my case, give lawyers a sense of a case, so they can decide whether to take it on or not. The questions I would ask were similar to the ones the children were asked in their credible fear interview, and to questions they might be asked by a judge. They’re ultimately meant to prepare a child to stand in front of a judge and contest a deportation order. I had been putting together that archive for the purpose of my self-education. It’s probably because of this archive, and this form of the questionnaires, that Tell Me ended up taking the form of the questionnaire.

There are always fingerprints of the archive in my books—my books are both the book and an archive of the book. So this archive [made for court] became the archive for Tell Me, and was engulfed by Lost Children, even though, chronologically, I started writing Lost Children before I wrote Tell Me, which was an appendix that grew out of writing Lost Children. I stopped writing Lost Children for about six months when I realized I was using the novel as a vehicle for my political frustration and rage, which is not what fiction does best. So I stopped and wrote this essay instead. Once I had been able to do that, I could go back and continue writing something as porous and ambivalent as a novel.

Mary Wang: Tell Me veers close to journalism at times, but also questions the sufficiency of such an approach.

Valeria Luiselli: It’s an essay in the most classic sense of the term, a way of meandering and approaching a subject without necessarily answering any questions. As a reader, I like essays that don’t give conclusions, but reflect a thought process as it is happening. One of the things I was grappling with was how narrative, as mediated by mainstream spaces, usually leads to an impoverished understanding of the situation. Standard journalism seems to have a scaffolding of a story already, a narrative into which it feeds content. Whether it’s with a picture of a suffering boy or a train filled with bodies, it rarely makes the effort to break apart from the accepted narrative and listen and look more carefully.

3. “I always write in a very intense dialogue with books.”

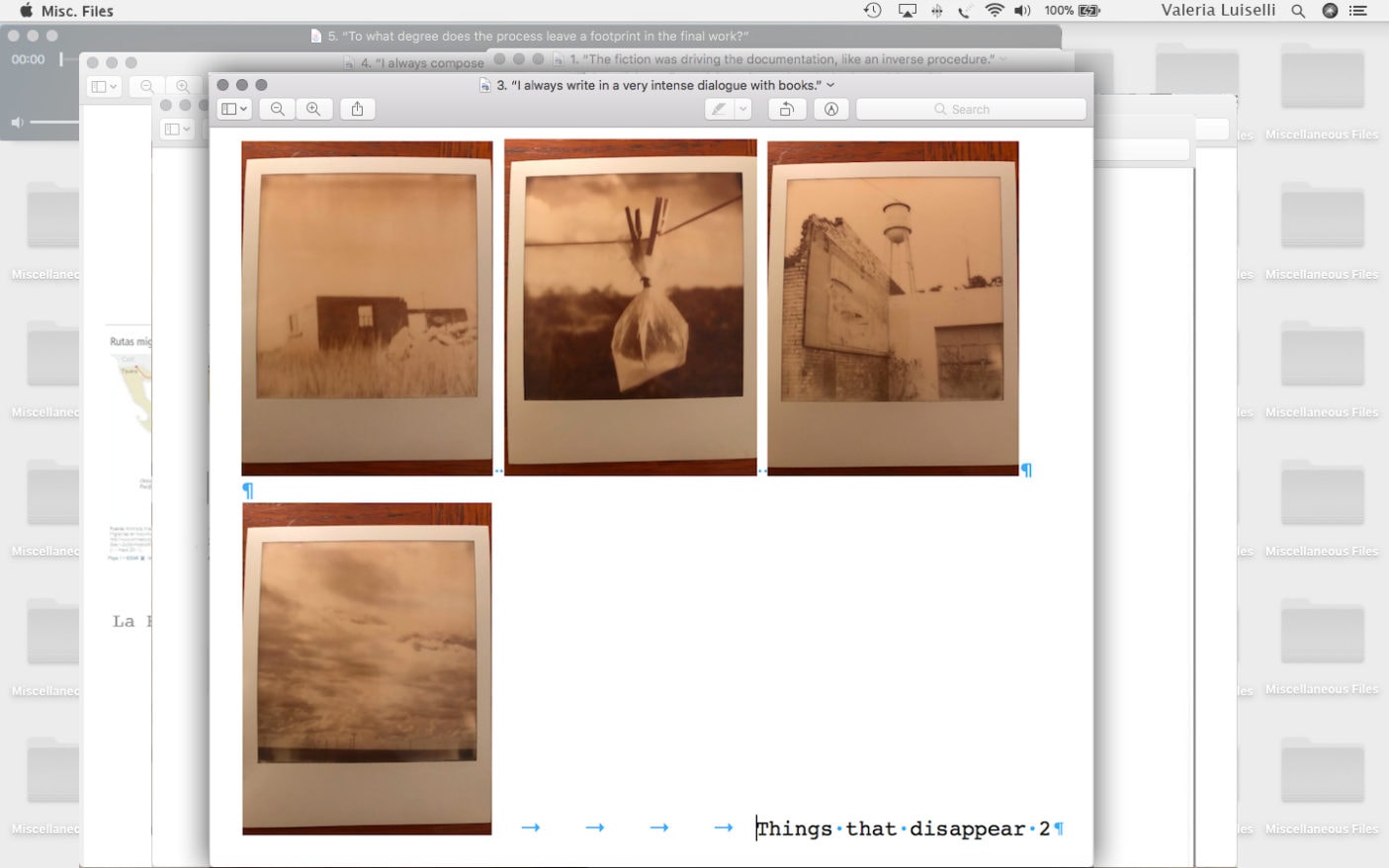

Mary Wang: Can you point out which of these Polaroids are “original” and which were added later? At what point in the process were these Polaroids taken?

Valeria Luiselli: I don’t think I can. The reason none of these are in the book—although I regret a couple of them not being in it—is that some of them, like the one of the water bag and the one of the water tank, are obviously taken by an adult eye that’s been trained to see things and frame things in a way that’s conventionally beautiful. I thought that kind of overwrought vision of the world was not in tune with the gaze of the ten-year-old character.

I thought a lot about which pictures would come in—I had more than 70—and in what relationship they would stand with the text. One option was placing them within the body of the boy’s story, but then they would have been there just to illustrate, which is a very uninteresting textual-graphic relationship. Or they could be in a box of their own, which is what I decided to do in the end, as a different form of documentation that the boy is giving to his sister, on top of his audio documentation. I decided on this method because the novel is essentially about ways of documenting, ways of telling, and ways of creating an archive—whether truthful or fictitious—to hand a story down from parents to kids, from kids to kids, and from kids to parents. Everyone in this novel is creating an archive to tell a story they want to tell in their own way.

The pictures existed before the book, or at least half of them did, so they played an important role in what I decided to narrate. Before I started writing, I had already taken notes for a year, and I exhibited the pictures at the Akademie Der Künste in Berlin. I was doing a residency there, and I was able to really spend time, the way you can only do with residencies—I have children, so I never have time!—to just look at the pictures and think. I was able to sit in front of all those pictures and physically arrange them into sentences. It was in the arrangement of that material, together with the archive I already had with the questionnaires, that I started to compose a story.

Mary Wang: On top of being archives, your books are also always libraries of other books. At what point do other books come into play while you’re writing?

Valeria Luiselli: They’re always there. When I’m writing a book, I always have a special shelf next to my desk where the only criteria is a book’s relationship to what I’m writing. It’s like a curatorship of books that come and sit next to me for the purpose of writing. This bookshelf is there throughout the whole process—I always write in a very intense dialogue with books.

Mary Wang: In a way, Lost Children is a canon in miniature of books that speak to the archetype of journeying and migrating. Considering that you’ve grown up in so many different places, each with their own educational systems and literary canons, what is your relationship to literary canons, and how have you built up your own?

Valeria Luiselli: That’s a question I kept returning to in my head in the past few days. I’ve been in New York for ten years, but the bulk of my books were in Mexico during that time. There are books I bought here, though not that many, because when I was studying for my PhD—the moment in my life I was reading most intensively—I was just using library books, hundreds of them. I didn’t have the books I came of age with. A year ago, I bought the house I’m in now, which is a big, old house in the Bronx with a lot of space, so I was able to bring my books over from Mexico. The boxes arrived some months ago, and finally, a week ago, I started opening them and shelving the books alphabetically. I kept laughing looking at the shelves, because I realized it’s such an x-ray of the Latin-American canon, even though I grew up in South Korea, South Africa, and India. It’s mostly philosophy and poetry. Almost all the philosophy is German—a lot of Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Gadamer—and most of the poetry is French. I have less fiction, but most of that is Russian and Latin American, and then there’s Anglo-Saxon modernist poetry. That’s the constellation. There are so many things missing, as always, and some things I only added in the past years. Growing up, Asian literature was not really in the panorama, and there was definitely very little from the African continent. As Latin Americans, you basically grow up conceiving of the canon as European. We are trained to see Europe as the norm, so there’s a lot to work on.

Mary Wang: At what point did you make the decision to shape your canon in a specific way, or is it a collage of your experiences?

Valeria Luiselli: I was studying philosophy in Mexico, so a lot came from that, though the proportion of Latin American philosophy we read, and still read today, is very slim. At some point, as a student there, I did start seeking out Latin American philosophers. But as we all know, it’s very hard to push back. Everything is built so that you cannot see what is not seen. I am much more conscious now about digging for things that are not obvious. The way I compose my library now has a lot more to do with a political stance: pushing back against the canon and looking for other things. I wish I started that ten years ago, and not five. It’s an un-education and a reeducation.

But, to defend the Latin American approach to the canon, at least we are readers of several different languages and literatures. The average Latin American that devotes his or her life to reading—and has an active interest and the opportunity to read books—will have read the Russians, the French, maybe some contemporary Nigerian writers, and some Japanese writers. It’s less insular than the Anglo-Saxon culture of reading. Translation is not even an issue there as it is in the US—it’s always been done. The US is the second largest Spanish-speaking country in the world, just second to Mexico, and yet, Spanish is treated like a foreign language here, one that educated people don’t speak—people might rather learn French or Italian. The literature of the American continent is not absorbed as part of the literary canon at all. As a Spanish speaker here, it’s difficult to understand.

Mary Wang: You wrote Sidewalks when you had just moved back to Mexico. You were teaching yourself how to write in Spanish. What was that process like, and how did that correspond to the canon you were establishing back then?

Valeria Luiselli: I had started reading in Spanish before then. All my life I grew up reading in English, because I went to the American school in South Korea and South Africa, and I attended an international boarding school in India. There was a group of Latin Americans and Spanish people in India, and we had a very good literature teacher. That was the first time I read the Latin American and Spanish canon, including Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, one of the most important poets of New Spain and Mexico, and Federico García Lorca, Gabriel García Márquez, and Julio Cortázar. It was a school very focused on academics, and outside the classroom, we had a reading group. I guess we were missing our language—or rather, they were, since English was a natural language for me to speak everyday. There was a nostalgia for the language, and having a cup of coffee or a glass of wine and reading and discussing our literature was what connected us to our language and region. We read a lot of things out loud, learned things by heart, and had a relationship to our literature—which was the first time for me. That was when I started to write in Spanish for the first time, around 17 or 18 years old. A couple years later, I decided I would write Sidewalks about Mexico City, a city I had never lived in, and in Spanish, a language I had never lived in either. So my connection to Spanish came through that extra-territorial experience of the language in India.

Mary Wang: Does writing in different languages makes you embody different personas?

Valeria Luiselli: I don’t think so. I’m not gender-fluid, but I am language-fluid! One thing I love about living here, especially in New York, is its constant stream of Spanish and English spoken together in the same sentence—subverting each other, flowing into each other, modifying each other. I left a mop outside the other day, and it froze. My daughter said, “la mopa es friso.” “Mopa” in Spanish is a completely different word, and frozen is actually “congeló,” but it made complete sense in Spanish. It’s a pity that it’s so difficult to write with both at the same time—some have done it, like Sandra Cisneros, Junot Diaz, or, more interestingly, Gloria E. Anzaldúa. But even done as well as that, it’s difficult to reproduce how Spanglish works in your mind.

4. “I always compose with maps.”

Mary Wang: You sent me several maps. It speaks to the journeying your work always does, whether it involves you traveling yourself, your subjects traveling, or the documentation of travels.

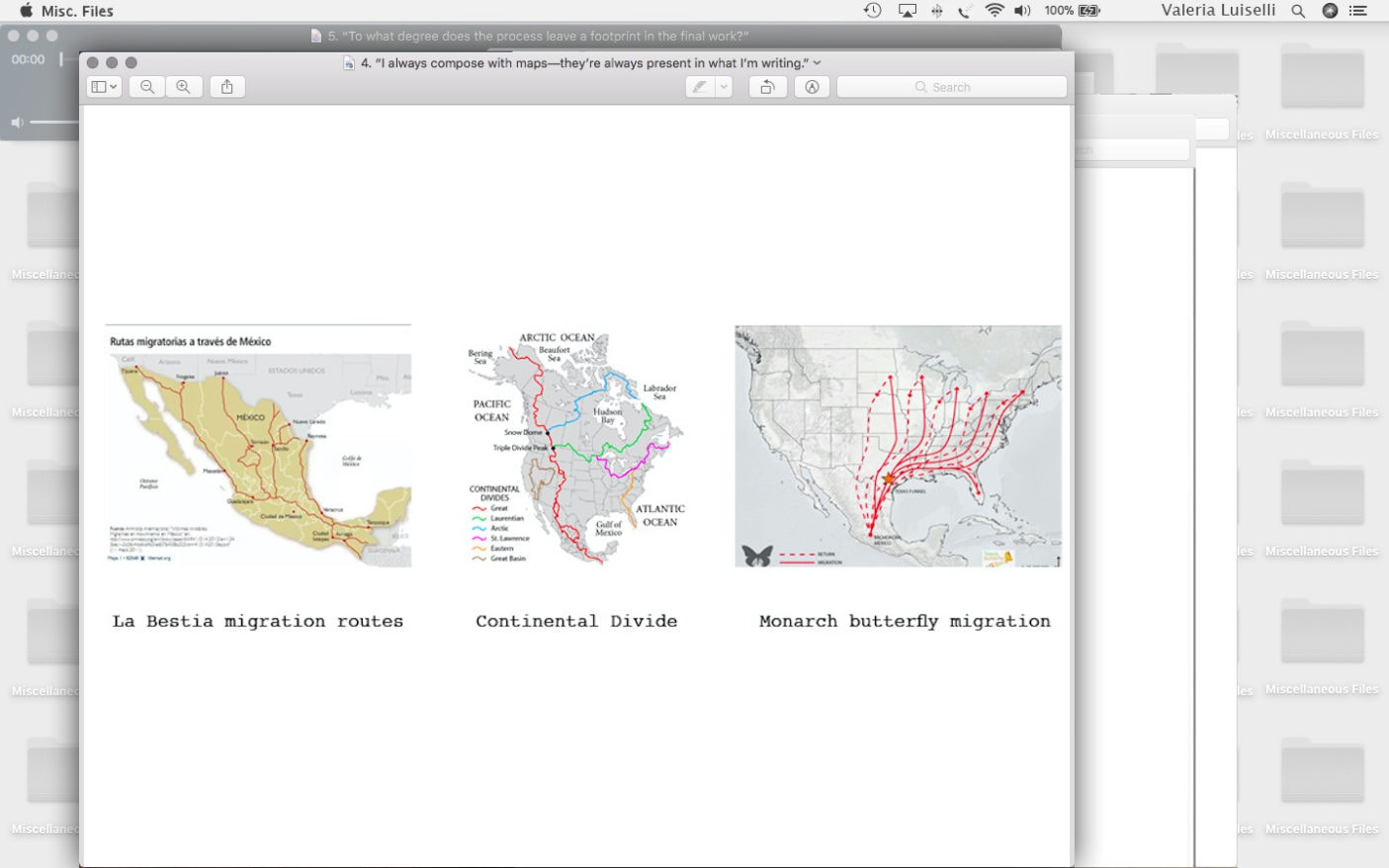

Valeria Luiselli: I always compose with maps—they’re always present in what I’m writing. With Sidewalks, it was maps of Mexico City, and many essays work as maps. With Faces less so, but for that book I kept looking at subway lines. With The Story, I navigated mostly through Google Maps, which is all I had. For Lost Children, I consulted many, many maps, including those of Apacheria, of what the Mexico-US border looked like in the 18th century. I recreated the family’s boxes, which I don’t dare open now, because they don’t feel like they’re mine anymore—they belong to this family. One of those has several maps, including a large one of the USA. It hung in my studio for five years or so while I wrote the novel. It’s marked everywhere, both for the real trip and the imagined one, where the novel goes off in its own direction.

When I was writing I also looked at continental divide maps and maps of migration routes. One thing that struck me was how, in this continental divide map, the red line goes from Chiapas, the most southern state in Mexico that shares a border with Guatemala, up around Mexico City, and then up toward the north, crossing through the US at the Arizona-New Mexico border, which is exactly where the heart of the novel unfolds. That is the route migrants crossing from Central America through Mexico follow as well, and that’s where the train they take [also called La Bestia] passes. So I found this strange and eerie coincidence, in which the continental divide and the migration routes are in such tight symmetry. There’s another map that shows the route of Monarch butterflies migrating, which is also the same route.

5. “To what degree does the process leave a footprint in the final work?”

Mary Wang: This file speaks to the question of how we document movement in text. You can picture how fast the train is going by listening to how fast the words are passing by. You document many movements in the novel, from continental migration to the movement of echoes, which felt very audible to me.

Valeria Luiselli: It’s precisely that—they’re time markers. That’s the big question when writing a novel: How do you create and recreate a unique experience of time? When I write from the boy’s perspective, it reads in a very different rhythm. It’s a different speed and perception of time, maybe closer to how children experience time. The female narrator is documenting the present from the viewpoint of being remembered, from this sense of retrospective future. There’s a sadness, a slow, more meditative relationship toward what she’s looking at, because she knows she’s looking at it for the last time.

When you stand in front of a train, what do you actually see? I Just stood there and documented that, and I was able to write how the boy—the only one in the group [of migrating children] who knows how to read—reads the words on a passing train in order not to be paralyzed by fear. At the same time, it makes him into a target. I like thinking about this question a lot: To what degree does the process leave a footprint in the final work?