Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Some friends and I started a group chat to share the micro-aggressions that we experience daily. When these encounters feel too minuscule to say out loud, for fear of being disregarded or dismissed as the Black Person Who Cried Racism—like when a woman flips her blonde hair back into your face on the train, and a strand gets caught between your lips—we bring them to the thread. We also share the eulogies and photos we’d like the media to use should we be shot by a police officer—photos that don’t make us look like we deserved to be killed. We send suicide notes along with LOLs and memes of Joanne Prada. We named the chat Spiraling. The tragedy is effervescent, but the validation helps us survive.

Morgan Parker’s poetry collection Magical Negro collects and dissects these everyday acts of violence, and sets the invisible in verse. Parker’s words penetrate the bone and dig into the marrow, illuminating the fracturing that remains as consequence of living while black: Like the emails from white allies attesting to the importance of change, “now more than ever,” as if it wasn’t urgent enough over the last 400 years. Or when I’m counting the number of days between Independence Day and Juneteenth. Parker’s words are visceral and potent, while her comedic delivery makes stones go down like silk. “The hunted must be clever,” she writes in one of the poems, Toward a New Theory of Negro Propaganda. “The hunted has two primary tools of survival: imagination and hyperbole. Where the Negro might see luck in a collard green, the White might see $7.99 per pound.”

Shifting between the Atlantic slave trade and pop culture—Angela Bassett smoking a cigarette in a bathrobe, Diana Ross eating a rib—Parker centralizes the triple-consciousness of black womanhood in an exploration of consumption and being consumed. Much as she did in her first two poetry collections, Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night and There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, Parker begins with her own interiority before moving outwards to examine the racial and political context. Poems like I Feel Most Colored When I am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background: after Glenn Ligon after Zora Neale Hurston examine the way the world engages with “black bodies,” and the way black beings begin to resent the melanated container in which their souls reside.

In Magical Negro, Parker suggests that the magical does not represent the fantastical, but rather the insistence of black people on existing, spectacularly. Hence, the title of another poem in the collection, We Are the House That Holds the Table at Which Yes We Will Happily Take a Goddamn Seat.

— Sasha Bonét

1. “I know they are asking me to check a box and I’m not going to do that…I love fucking up a form.”

Morgan Parker: Tinder sucks. The entire project of it is racist. There is this expectation for love and romance to be a simple, sweet part of life, and it’s terrible to me. It constantly makes me feel like, “How could anyone ever desire me?” The project of casual dating, of seeing a picture and swiping, is so biased against black women—even the algorithms of what pictures are shown are [biased]. I cite racism as the reason every time I delete the app. Even if only one person sees that, it makes me feel good to call a spade a spade. I have fun with things like that, because I know they are asking me to check a box and I’m not going to do that.

Sasha Bonét: Well, the boxes were not made with you in mind.

Morgan Parker: I love fucking up a form.

Sasha Bonét: You have a poem called Matt in the collection that reminded me of something the writer Kay Lindsay said: “While white women are sexual objects, Black women are sexual laborers.” In the poem, Matt is kissing you secretly in a bathroom stall, and you ask about his girlfriend, Ana. He ignores your query, instructing you to grab your ankles without regard for your discomfort. In such a polarized climate, how are you able to speak confidently about your consciousness of race in America, and just as openly about your attraction to white men?

Morgan Parker: I grew up as an emo kid, and I still love those Matts. Culturally, we all love those Matts. He’s just a nice dude who reads books. But Matt does not know the way he moves through the world, and that his existence has consequences. The Matts are always attracted to me, and I know how to relate to them, but it never ends well for me, because Matt will never choose me.

Sasha Bonét: Do you ever feel odd about bringing Matt to the cookout?

Morgan Parker: Matt doesn’t come to the cookout. There are parts of our lives that necessarily cannot be intertwined. And this hovers over the relationship. I just feel left out of the whole possibility of love and romance. I hate that that is related to my race, and I hate that I believe it. I hate that I have felt it for so long, and I hate that white women have it so easy. And it’s not that they are all beautiful or interesting—their face could look like a piece of paper, but there is a cultural perspective skewed towards them. We are asked to compare ourselves to them.

Sasha Bonét: White women are the model of femininity.

Morgan Parker: That really hurts my feelings.

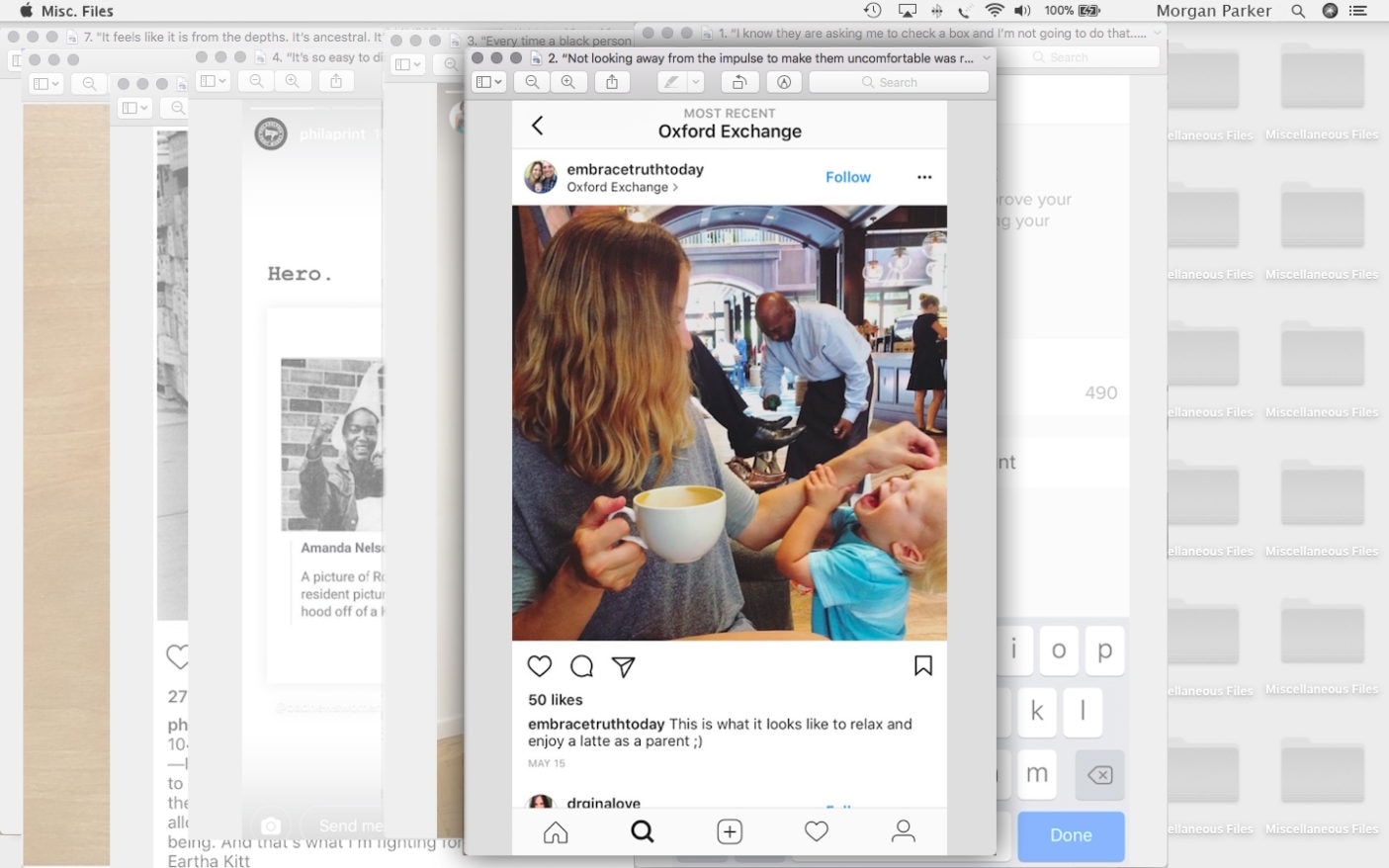

2. “Not looking away from the impulse to make them uncomfortable was really important.”

Morgan Parker: I did a reading last year at a place called Oxford Exchange in Tampa, Florida. It’s a book store and café, and there’s a shoe shiner there named Jimmy.

Sasha Bonét: This couldn’t be a better encapsulation of America and the obliviousness of whiteness. I can’t decipher if she doesn’t see him or if he’s background noise, doing exactly as he should.

Morgan Parker: Just the perspective is amazing!

Sasha Bonét: I hold a special level of disgust for white women who behave this way, because, as a person oppressed by patriarchy, you have a responsibility to confront racism, too.

Morgan Parker: I feel like this was the move from my second book to my third. White women loved the Beyoncé book, and they loved talking about feminism. They can kind of dip their feet into black feminism, but for the most part, it’s not more than camaraderie. Friends would send me photos of white women reading my book on the subway, and I wonder if they are going to stick around for this book.

Sasha Bonét: When you read at the 92nd Street Y, white women were seated on either side of me. It was like watching Get Out in the theatre; they were laughing at the wrong bits and looking over at me for approval.

Morgan Parker: I am uncomfortable all the time. Not looking away from the impulse to make them uncomfortable was really important. Previous readers may be confused because I brought them in with sequins, and now, it’s the transatlantic slave trade. They say they want to be allies in feminism, and then they perpetuate the problems. They deserve to be told that, and it’s not always easy.

3. “Every time a black person is murdered by a police officer, I get a Facebook message from an old friend confessing to me that their grandfather was racist.”

Morgan Parker: This is a Real Housewife of New York. Countess Luann de Lesseps in her Diana Ross Halloween costume. In this episode, other housewives tell her it’s a little racist and she insists that it’s not. It’s a clown suit.

Sasha Bonét: There seems to be an urgency in this collection. You are going for the jugular in a way that feels like you have no more time to waste with spoon-feeding.

Morgan Parker: I was seeing death everywhere when I was writing these poems in 2014/2015. Michael Brown hit me really hard, and it was that summer where so many people were being shot, and there was no justice. I felt that our feelings were not considered at all, by anyone. The fact that you are going to loop this kid getting murdered over and over in a bar. There is no value placed on me, or on black life.

Sasha Bonét: It’s terrifying that anyone could watch that with a beer or cold glass of milk and not feel sick.

Morgan Parker: Terrifying. I began to wonder, am I a person? Do I have a body? There needs to be an awareness of just how small we feel.

Sasha Bonét: In these moments, I find it strange when white friends come to you for coddling, just so that you may absolve them of their guilt.

Morgan Parker: Every time a black person is murdered by a police officer, I get a Facebook message from an old friend confessing to me that their grandfather was racist. Why do I need to know this?

Sasha Bonét: The black body is often discussed as if it is a container with no soul inside. You write, “The body is a person.”

Morgan Parker: I’ve reached my limit with that. The language became so repetitive. It hurts when you say, “the black body,” or “this black life.” This person has a name. They had kids.

Sasha Bonét: Yes. Black people just move through the day collecting and carrying all of these violent attacks, and then get home to see the Ancestry.com commercials.

Morgan Parker: Right! Oh cool, you found out you’re from Ireland, dope. Get away from here!

It all bothers me so much. Collected, all of these things contribute to me questioning if I can continue to live. We spend so much time caring for their feelings and choosing our words carefully. I’m tired of explaining.

Sasha Bonét: There is no explaining in Magical Negro. Editors often ask me to break down what certain language and cultural references mean, and I think this takes away from the potency of the work. In MFA workshops, they would say, “Can you break that down for me?” or “I don’t see myself in this.”

Morgan Parker: I recall talking to other black writers about this. Why do we have to break all this down? We are expected to be familiar with every Greek myth ever, and y’all can’t Google? That, in itself, is the privilege. It’s not important enough for you to educate yourself on it? It’s an unfair ask.

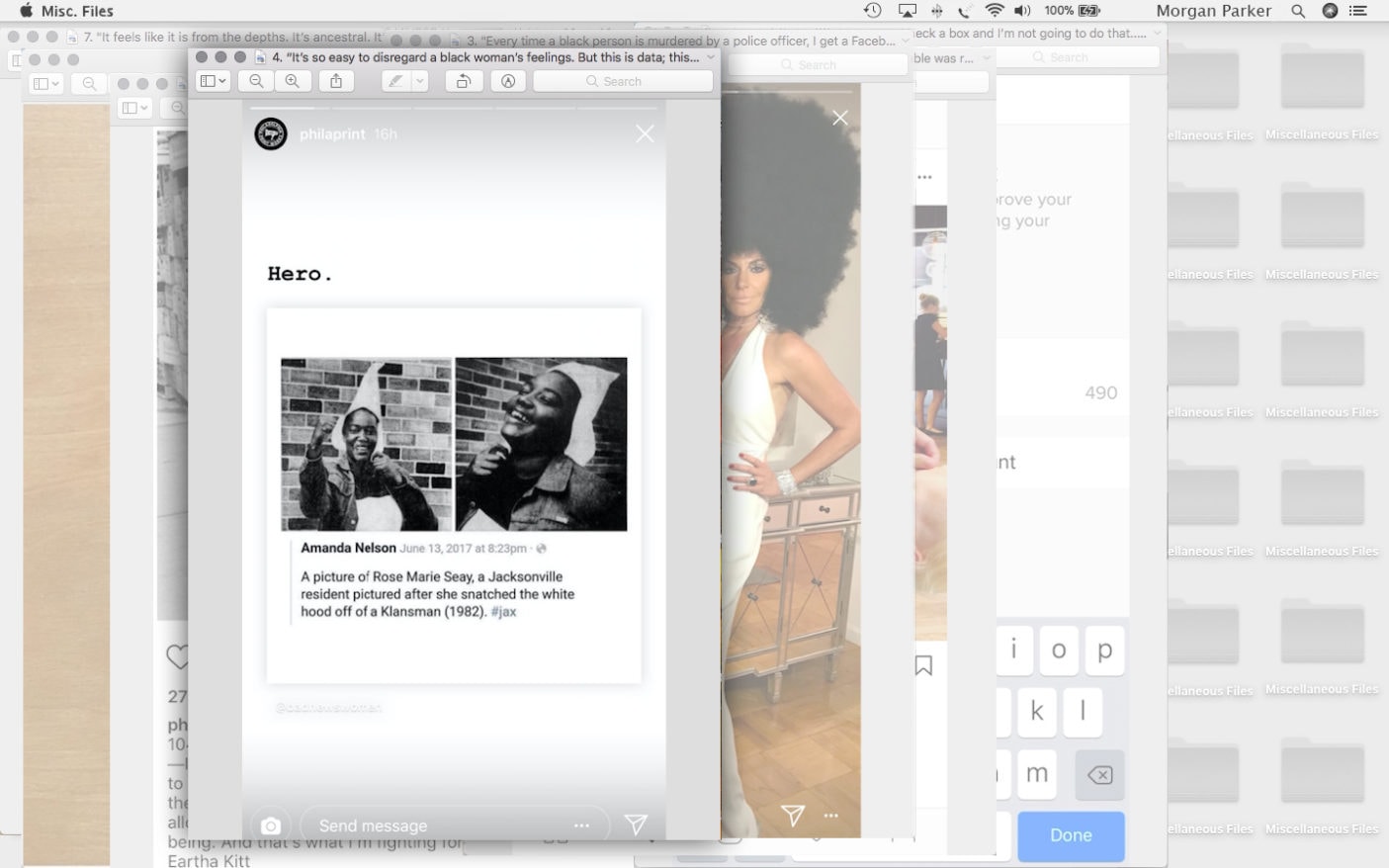

4. “It’s so easy to disregard a black woman’s feelings. But this is data; this is not just me emoting.”

Sasha Bonét: Imagine the danger she put herself in to be able to take this photo. And still, she smiles.

Morgan Parker: Look what we live with. These objects are constantly reminding us of terror. We have to constantly fight against it and try to make joy out of it. She’s flipping the whole thing on its head by wearing them as a costume.

Sasha Bonét: I love social media for things like this. When we can visualize these small victories, these reminders serve as redemption. This is the lineage that often gets erased.

In the book, you acknowledge that black people are occupying the past, the present, and the future, and point to all the mental work that goes into moving through the world in this way. So often people respond with something like, “Let it go, you weren’t a slave, and I wasn’t a slave owner. Move on.”

Morgan Parker: The gaslighting is what I really pushed against in the writing. I didn’t want anyone to read this and be able to argue against it. Or say that I was being dramatic. That’s part of the reason why I chose to use more academic language in some of the poems, because I know white readers can hear and understand that. They accept this language. It’s so easy to disregard a black woman’s feelings. But this is data; this is not just me emoting. I am making an argument. I know what a convincing argument sounds like to you, Matt. I know the language. I wrote the papers. What better way to put my Ivy League degree to use?

Sasha Bonét: Audre Lorde says, “You can’t dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools.” However, the code-switching you are doing from line to line resembles the kind of shifting that we are forced to engage in every day; yet, they have no idea about the double and triple consciousness that exists in a single moment.

Morgan Parker: I’m existing on all of these different planes: in one moment I’m here, then I’m in the future, then I’m on a slave ship. It is not recommended, but I can’t help myself. My therapist told me she doesn’t even know how I do it.

Sasha Bonét: In one line, you write, “I know too much.” You’ve also said that forgetting is a very American neurosis. The writer Eduardo Galeano said his biggest fear is that people in the Americas all have amnesia. Those observations feel very much aligned.

Morgan Parker: We forget that America started by someone coming from somewhere else and taking ownership of the land from Natives, and now they are policing who else can come in. It’s a very American insistence, to close a chapter and just move on.

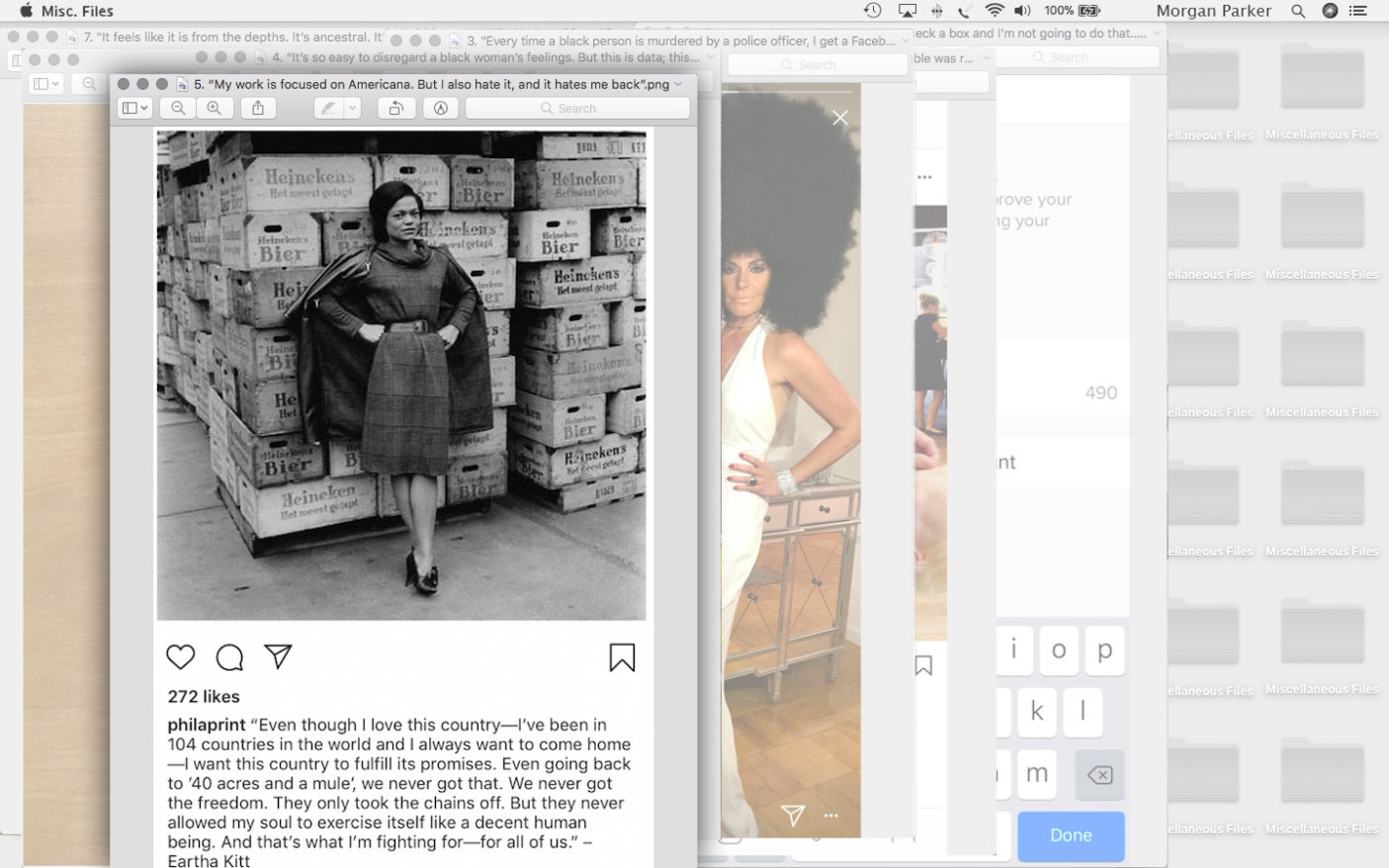

5. “My work is focused on Americana. But I also hate it, and it hates me back.”

Sasha Bonét: Do you agree with Eartha Kitt? Do you expect America to fulfill its promise to you? It feels like your work is pleading for that possibility. Or at least convincing the reader to consider it.

Morgan Parker: My work is focused on Americana. But I also hate it, and it hates me back. I want to love this country. I want to feel at home, at home. Black people have given this country so much hope, and we continue to believe that this country can get there. Even that belief is otherworldly. There is something really interesting about our commitment to this country and our attempts to make it work for us, to really try to change it, because our lives depend on it. Some people think change would be nice, but it’s not pertinent because they’re not going to die. I feel like I’m going to die at any moment. I don’t think this is the best country, but I would like to love it more.

Sasha Bonét: Your work is centered around a very American experience, and includes extensive references to American pop culture. You have a poem called Diana Ross Finishing a Rib in this collection, along with a piece on Eartha Kitt. It’s as if you have gathered all the memes and visual cultural references we cherish, and examined and dissected them. I would be curious to see how your work would function outside the US.

Morgan Parker: There are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé did really well in the UK. I was surprised. But American culture is so pervasive, and everyone is obsessed with it.

Sasha Bonét: The black US resistance has always served as a reference for black people in Europe. I can see how your work would continue this tradition. I also believe the diasporic experience has many similarities, no matter where you are.

Morgan Parker: That’s the blackness. We are connected to the colonialism of all these places. But this book feels like a hamburger and apple pie.

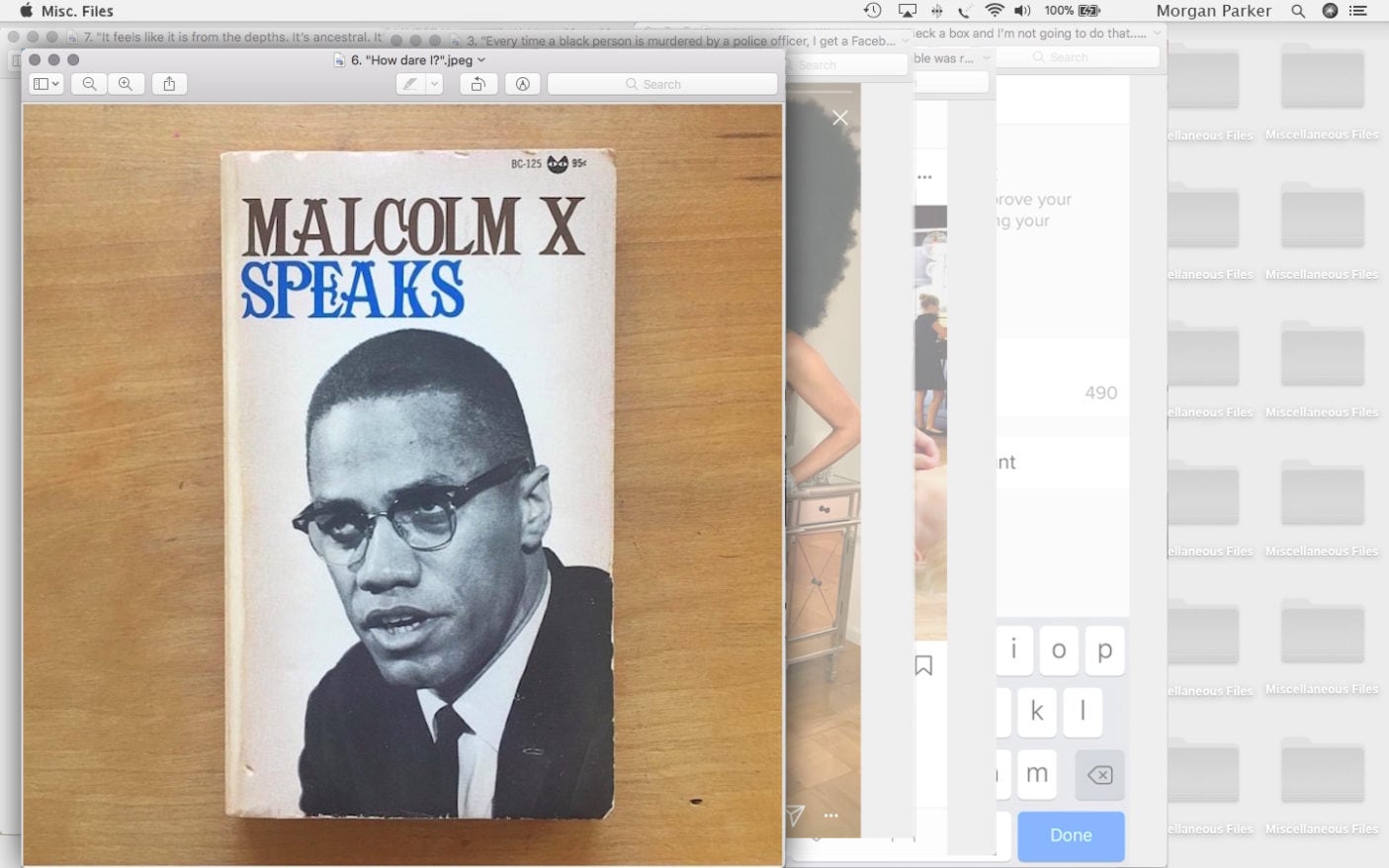

6. “How dare I?”

Morgan Parker: I like the simplicity of Malcolm X Speaks. I feel like all books should be like this.

Sasha Bonét: Your titles are very much in that vein. I was so drawn to Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night, because it does. All the time. Do you begin with the titles and work from there?

Morgan Parker: I wrote a postcard to a friend, and it was a weird collage of photos of Klaus Biesenbach and Kanye West, and I wrote on it, “Other people’s comfort keeps me up at night.” And when he got it, he said, “This is your book title.” It was just a thought I had, but it sums it all up. Comfort is explored throughout the book: the gall of others having comfort while I am so uncomfortable. And how do I create comfort for myself, and what does that look like?

Sasha Bonét: Magical Negro feels like an answer to this. In poems like Magical Negro Brooklyn, you explore the many different ways to heal and preserve, all while moving deliberately, with audacity. I even heard you say at a reading, “The nerve of me.”

Morgan Parker: Yes, I have some nerve. There is an awareness of how many moorings are being trespassed at any given moment, and that audacity really came out in this book. In the back of my mind, I’m on a slave ship, yet I’m also here just telling you how it is. How dare I? We are doing that in so many small ways every day. Trespassing what has been laid out for us, in terms of what we are allowed to be. Tearing apart those boundaries all the time. That’s the magic. It’s not any otherworldly powers. It’s just amazing that we are able to continue, and so creatively.

Sasha Bonét: You write, “We don’t pray anymore / the way our parents taught us.” I thought that was powerful, because prayer was always a means of escape. Our parents wanted to give us something to rely on besides them, because they understood the imminent threat of death. And many of us are abandoning this.

Morgan Parker: We found another way. We are up to something else. We may not be entirely sure what it is, but it’s not the church. I wanted to explore institutions, including religion—mostly white religion. I went to a conservative Christian school where white people taught me who I was. My understanding of my identity was backed up by scripture, so they could tell me what my fate was. In going back to undo that white supremacist hold, part of that was in religion.

7. “It feels like it is from the depths. It’s ancestral. It’s larger than me.”

Sasha Bonét: Is it true that you wrote many of these the poems in Magical Negro in one take? Like they were spilling out of you?

Morgan Parker: Yes, but that’s not how I usually work. When I went back to look at the manuscript, it was crazy. Several people helped me write this, and it feels like it is from the depths. It’s ancestral. It’s larger than me. My hope is that we recognize, on a more nuanced level, what the experiences of others are like, and that we consider that in our relationships. There has to be some good that comes out of me.

Sasha Bonét: I’m not even sure how you went back to edit these poems. Many times I had to put the collection down, take a few deep breaths, and come back to them. Especially reading A Brief History of the Present, when you write, “Which is greater, the amount of minutes it takes for requested backup to arrive at the scene of a twelve-year-old in a park playing with toys, or the varieties of insects that might make contact with a person laid in a street over the course of four hours on a summer evening in St. Louis? How patient must we be? Praise the endurance.” That is heavy.

Morgan Parker: Even for me, reading these poems is horrible. I don’t know how I will make it through the book tour.

Sasha Bonét: Tell me, what is happening with the search for affirmations? Is this a part of your practice?

Morgan Parker: I was looking for an affirmation podcast to listen to before I go to bed. To say some good things to myself, because all day I’ve been saying bad things to myself. I was like, Of course. There is nothing found for you. You don’t get an affirmation. Some error could have occurred, but I’d like to look at it as the universe telling me, “No way.”

Sasha Bonét: There is nothing we can give you to make this better. You go to the schools, you adjust to the language, you code-switch, you follow the prescription…and still.

Morgan Parker: We grow up. We try so hard, and then all of sudden we realize it doesn’t matter. How do you recalibrate, knowing that they can do nothing for you? How do you reprioritize when you take away the delusion that the whole world is putting on you all the time? It’s hard to resist that delusion. We’re just a body. That’s all people see. This is how it’s always been. That is the impetus for the book: me trying to figure out how to make sense of that.