Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

When I sat down with Helen Phillips in her Brooklyn apartment, I told her that I related to her latest novel, The Need, not only as a potential mother, but as a human being who has the tendency to interpret minor events as signs of impending disaster. That’s certainly the way Molly, the novel’s protagonist, navigates the world. As she raises her young children, Molly starts to mistake tangled threads for giant bugs, and believes the rumblings of the garbage truck to be the onset of an earthquake. Though she is a skilled professional—a paleobotanist—she’s less certain of her instincts when it comes to her children. When a light bulb explodes into splinters of glass, she tells her children not to move, consciously “quoting what she remembered adults saying in such situations when she was a child.”

Despite the subject matter, our conversation was lively, profound, and filled with laughter. This is in part because we discussed how imagining errant possibilities isn’t just the idiosyncrasy of an anxious mother, but also the aspiration of the novelist and the responsibility of art-making itself. The other part is our joint understanding—and perhaps commiseration—that moments of great grief in our lives have often been accompanied by particular joys. This applies to Molly too. When she encounters an intruder in her house, she fears for the lives of her children—but it’s precisely this event that leads her to understand the beauty of the repetitive, mundane movements of her mothering.

Like Phillips’s previous novel, The Beautiful Bureaucrat, in which a woman takes an administrative job at a mysterious database that’s as big as the universe itself, The Need nimbly maneuvers between the real and the speculative, leading us to the existential questions that rarely yield simple answers. Perhaps that’s why I was reminded of Phillips a few days after our conversation, when I joked to a friend that kids in New York are like the weeds between the cracks of the pavement: they grow and flourish despite not being given the space to do so. As soon as I finished the sentence, I realized I wasn’t only talking about the kids, but life in its entirety.

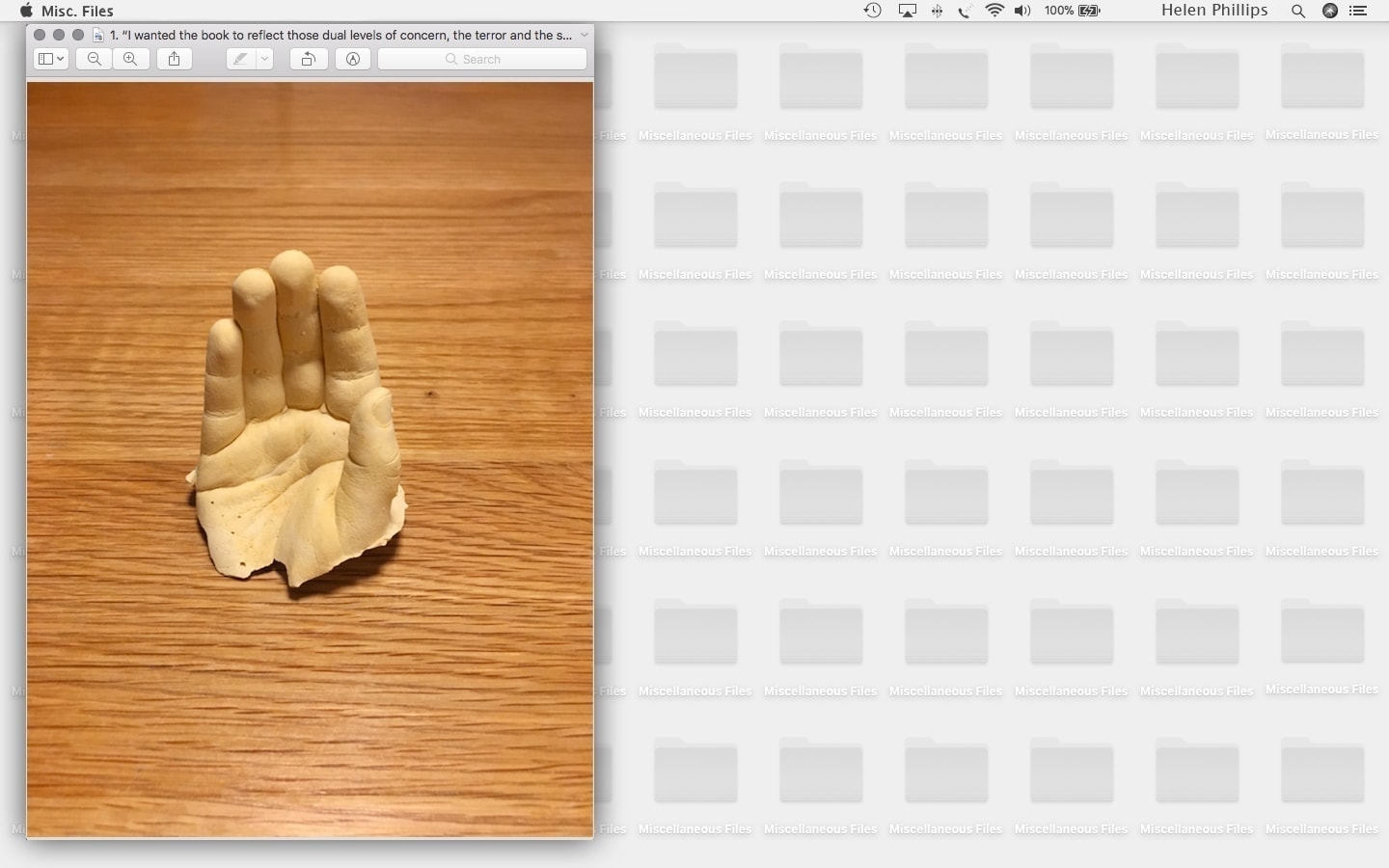

1. “I wanted the book to reflect those dual levels of concern, the terror and the sublime.“

Helen Phillips: This is a cast of my daughter’s hand. We have a very nice dentist, who made it for us when she was three. There’s something so precious, but also vulnerable and eerie about it. Having children has made me realize there’s a real evolutionary purpose to having an imagination—I imagine bad things happening to my children so I can prevent them from happening. There’s a line between being neurotic and being very sensible, and, as a parent, it can be very hard to understand which side of that line you’re walking on.

Mary Wang: There are two sources of tension running through The Need. One is about how Molly will deal with the intruder; the other comes from everyday mothering. Will I get my kids to eat? Can they be in the supermarket without making a mess? Will I get through the day?

Phillips: Yes, the mundane and cosmic stresses run alongside each other in the book. I believe they also do in everyday life, as big ideas are embodied in concrete moments and intimate interactions. As a parent, you spend so much of your time cooking, cleaning, and doing housework. At the same time, every day I spend with my kids, I have this flash that goes by and says, I can’t believe I’m raising human beings. I wanted the book to reflect those dual levels of concern, the terror and the sublime.

Wang: It’s also a testament to a mother’s work, which is often undervalued. The novel foregrounds the stresses of motherhood over that of Molly’s work as a paleobotanist, as if arguing that the former is at least as challenging.

Phillips: Early readers have remarked that the book evokes aspects of motherhood, like breastfeeding and using a breast pump, that aren’t often seen in fiction. That’s often because those subjects aren’t considered worthy of it. As a working mother, you’re always navigating the interface between your identity as a mother and your identity as a working person. People might feel a shakiness in their identity during that time. It’s certainly how I have felt, and it’s something Molly toggles.

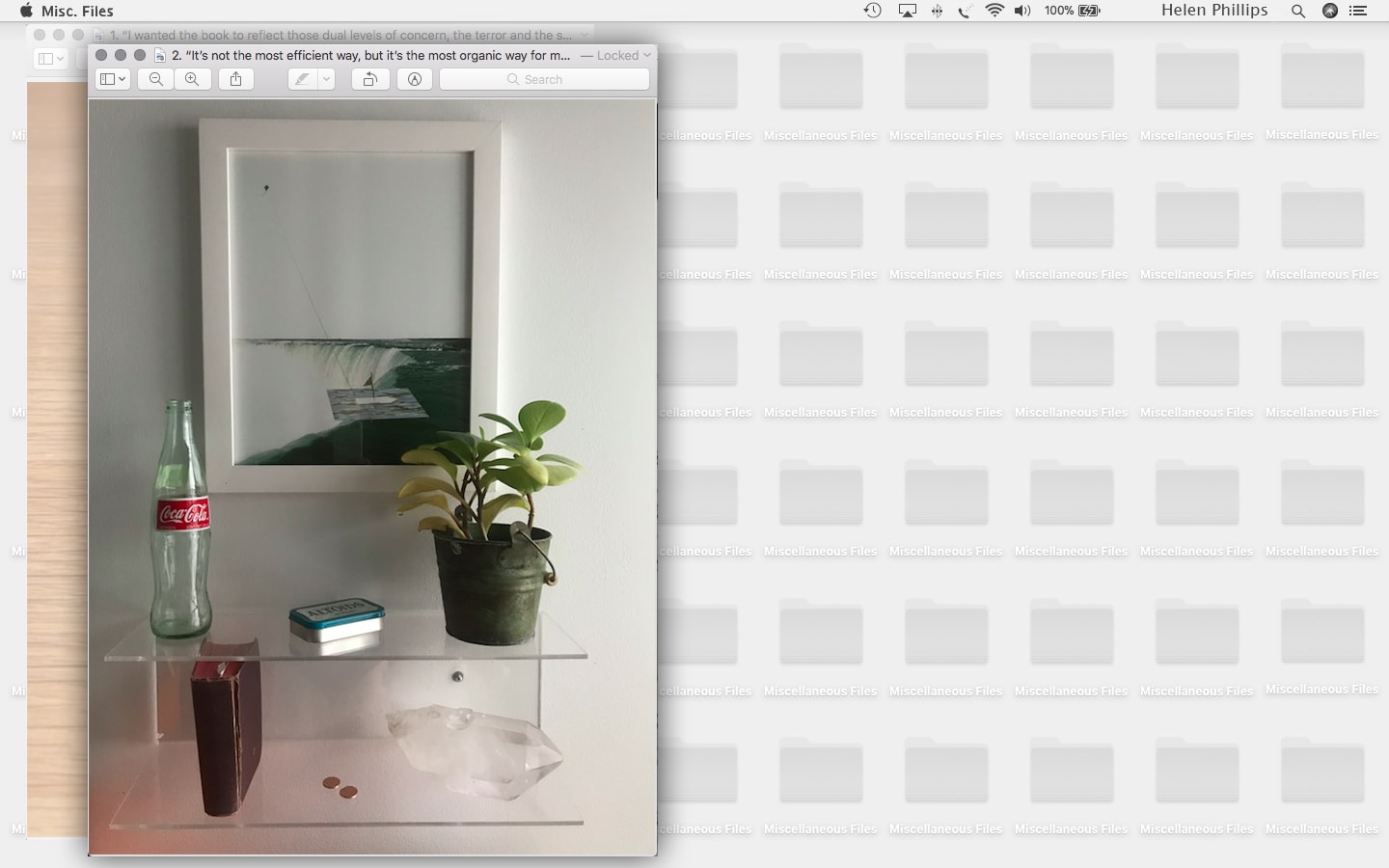

2. “It’s not the most efficient way, but it’s the most organic way for me.“

Wang: You said in another interview that you often start with images, from which the plot later emerges.

Phillips: I was on a panel a while ago, and we were asked what comes to us first when we’re writing a novel. One person said plot, the other said character, and I said image. It’s different for everyone. I attended Karen Russell’s book launch recently; she said that for her, it’s setting. For me, my books begin as hundred-page lists of images, overheard dialogue, and newspaper headlines. But the core images are always the first things that are present, and the plot is born out of them, rather than the other way around. It’s not the most efficient way, but it’s the most organic way for me.

Wang: What were the first images for The Need?

Phillips: There was this moment when my daughter was a baby, and I was home alone nursing her, naked. My husband was out for the night, and I heard a sound in the other room. I hovered in that instant, thinking about how I’m nursing, naked, and alone. I had to write about that feeling, because it was so primal.

I also had an image of these mundane objects that are like the objects we use all the time, but slightly off. I got this Coca Cola bottle and Altoids tin from the bodega, objects we take for granted because they’re so familiar. These became the objects Molly finds at her excavation site, which ties in with a larger idea: Molly takes her life for granted, but by encountering the intruder, she realizes that the daily grind of being a working parent is perhaps the most precious thing.

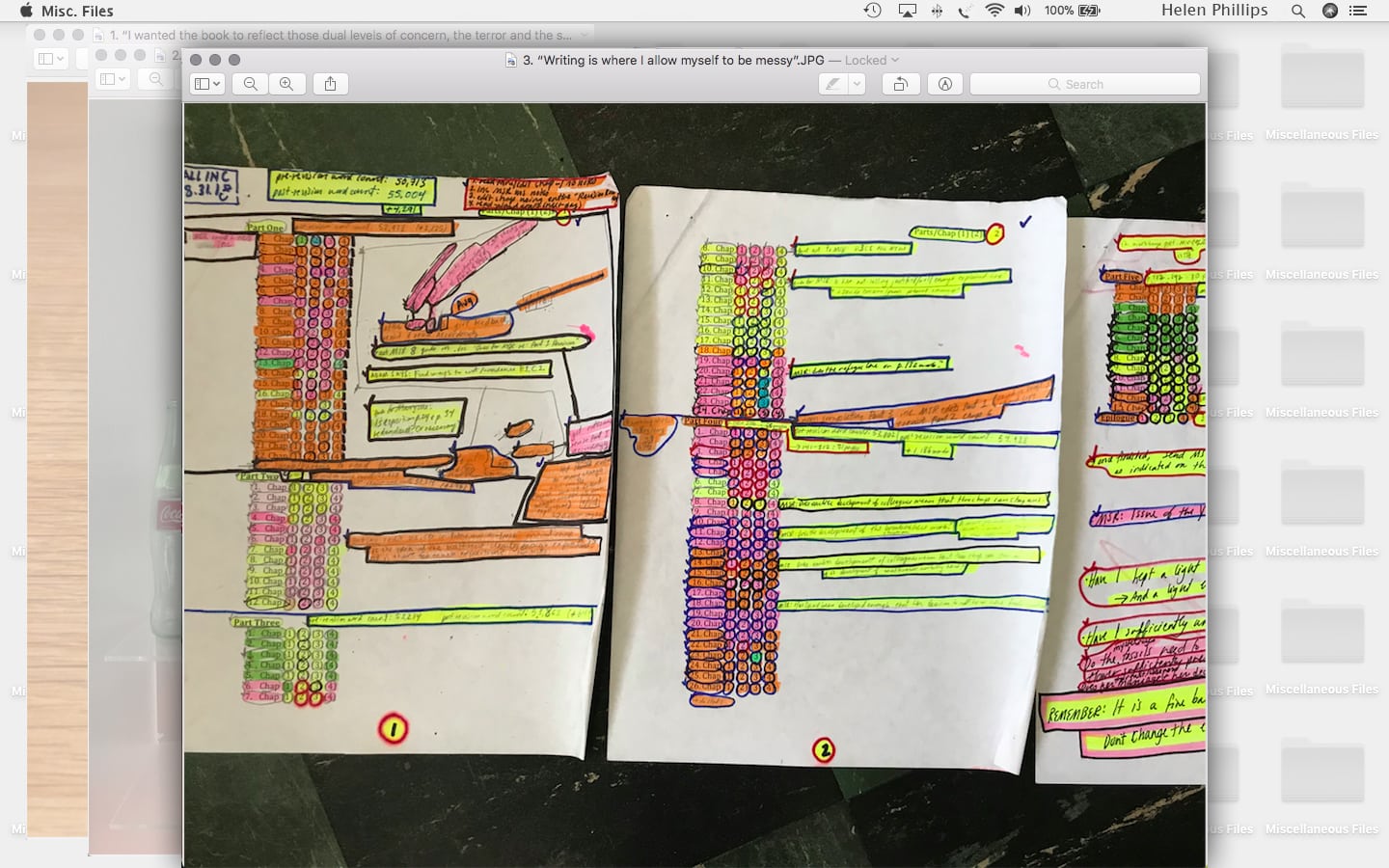

3. “Writing is where I allow myself to be messy.”

Wang: How did we get from those first images to this stage?

Phillips: This is from the summer of 2018, which was very late in the process. I listed every single chapter of the book, and the four numbers indicate my four steps of revision. Step one is reading through the chapter and looking at anything that jumps out, step two is incorporating any changes suggested by my editor, step three is looking through this running list I keep of all the questions, doubts, and self-criticisms that emerged along the way—knowing that I’ll be addressing my concerns during revision prevents me from getting stalled when writing. And step four is reading it aloud. I was on a very tight deadline for the book, so I had to have a way of marking each step, because otherwise I’d feel as if I wasn’t moving at all. I was writing at least six hours a day last summer, and a lot of the book was formed by that time.

Wang: I can tell from your plots that you have this organized side. There’s a rhythmic, propulsive quality about them. They’re intricately fitted, yet headed in a clear direction.

Phillips: Reading a propulsive plot is exciting. In my early drafts, plot is one of the weaker elements. My first draft to my second always shrinks. When I pare it back, I get more to the essential actions of each part. Also, my husband is wonderful at talking about plot. When I worked on this book, we would talk for hours about how things would flow. I would be inclined to have certain elements simply fade out, but he motivated me to have a great plot, because, why not?

Wang: Speculative fiction creates new worlds by both providing and withholding details. That seems especially the case with your work, where so much is left unsaid. You’re actively relying on the reader’s ability to assume things.

Phillips: Especially in this book, I wanted to focus on the central relationship and only gesture at these other possibilities. But there’s also another aspect: In my first book, And Yet They Were Happy, I gave myself the challenge to make all the stories exactly 340 words. I could write about anything I wanted to, as long as it stayed within that limit. So I would write 1000 or 800 words very quickly, but I’d spend most of my writing time editing that down. Strangely, having one rule made me feel very free. This is not unlike my process of writing a novel. In the first draft, I accept all the messiness, and in revision, I sculpt out of that raw material. It also takes the pressure off of the first draft—which I actually call my zero draft.

4. “Birth and death coincide in life, as do grief and joy.”

Wang: You’ve said that you write speculative fiction to comfort yourself. Was there something about motherhood you wanted to comfort yourself about?

Phillips: All my writing arises from my anxieties. Writing about them is a way of acknowledging them and learning to live with them. The Need is dedicated to my sister, who died when she was 32, when my daughter was eight weeks old. That was a very intense summer of birth and death. That’s what I was trying to write about in this book: What do you do with the fact that people’s children die? When I was falling in love with my newborn daughter, my parents had just lost their daughter. Every moment when I’m at home loving my children, there are parents around the world who don’t get that privilege—think about the crisis at the border. Birth and death coincide in life, as do grief and joy.

Wang: A lot of your work lives on this precipice of joy and disaster. The protagonist in The Beautiful Bureaucrat, Josephine, engages in these associative word plays. One of them jumps from the word marriage to the word miscarriage.

Phillips: We’re always living above the abyss. We can forget about that, but language is a pathway that can pull away that curtain. You’re sending a cute text, but suddenly death creeps in—little coincidences of language can open the gulf under me. But living with the awareness of the abyss is probably a good thing. Italo Calvino has a story in Invisible Cities about this city, Octavia, that’s built over an enormous chasm. He offers a beautiful, airy description of this city made of ropes. Everything is tied together, and people hang their plants and sleep on hammocks. He ends by writing, “Suspended over the abyss, the life of Octavia’s inhabitants is less uncertain than in other cities. They know the net will only last so long.”

Wang: The push and pull of the abyss is inherent in motherhood. The birth of your children reminds you of your own aging. The growth of your children propels you toward their impending departure from your life. Coincidentally, I had a miscarriage while I was reading your books in preparation for this interview. Besides the physical and emotional pain that comes with the event, I also experienced it as something that was mystic and sublime. It was horrendous, but I also felt as if I’d encountered something that was above me.

Phillips: I’m happy you’re speaking about miscarriage. I had one too, and it’s one of those things that’s not talked about.

Wang: And certainly not written about much in fiction.

Phillips: The Beautiful Bureaucrat was my miscarriage book. In a way, some of its ideas are very similar to The Need, like the idea that a simple glitch could change the path you go down. My sister had a rare neurological disorder called Rett syndrome. She was born apparently healthy, but stopped progressing at one year old. She had started to talk a little, but she eventually lost that ability. This is all because of a genetic mutation that happened to her, but not me.

We don’t talk about miscarriage enough. When it happened to me and I mentioned it to people, it turned out that so many people had also had them. And I had known them for such a long time without knowing they had gone through that. Certain female experiences are characterized as shameful; it’s the same as breastfeeding. Until I started lactating there was almost nothing that I knew about it, even though it’s a relatively common human experience and a big part of your life when you’re doing it. I didn’t understand why I didn’t know anything about it.

Wang: Being a writer or an artist is helpful in that way, because it provides a channel for processing certain feelings.

Phillips: The Beautiful Bureaucrat helped me a lot with that set of emotions. My books are not autobiographical, but they are a way of trying to understand these human experiences that I can’t explore through realism. Making it surreal or speculative enables me to confront it head on.

Wang: Reading The Need reminded me of how aspects of motherhood are already so surreal. The acts of gestation, breastfeeding, giving birth, though so commonplace, can also feel like bizarre bodily experiences.

Phillips: Absolutely. Realism doesn’t describe these experiences. When you’re in the twenty-fifth hour of labor, and you’re having hallucinations, that is surreal. Having sex for a few minutes, which then leads to a life—what could be crazier than that?

Wang: Has motherhood changed your work, or how you work?

Phillips: One change has to do with the writing process itself. I have dramatically less time to write. Before I had kids, I had an administrative job and taught night classes, but I was able to fit in three or four hours of writing in the morning. After I had kids, my average of four hours a day went down to one hour a day. And that’s only from Monday to Friday, so it’s five hours a week. It depends on the time of the year, too, and thankfully my husband is an artist, so he can be flexible. I tell myself it’s quality over quantity. Sarah Manguso once said something to the extent of: I don’t want to read books by people who actually have time to write them.

The second way motherhood has changed my writing is in terms of subject matter: it became so urgent for me to try to understand the intensity of that love, the intensity of being responsible for another human’s well-being, the intensity of knowing that you cannot protect your children from every threat.

5. “They’re not exceptional people, but they are forced through circumstance to take action.”

Phillips: I’ve listened to this album so much, I know it like the sound of my own thoughts. Eno wrote it to help chill people out at airports, and he has also written music for hospitals. I think he’s very good at what he does. I listen to it when I’m writing around other people—in a café or a shared office—and need to create the feeling of solitude. Incidentally, it’s also what I listened to when I was in labor with my children.

Wang: Eno described his Ambient series, of which Music for Airports is part, as “as ignorable as it is interesting.” A lot of your characters occupy a similar threshold between mundaneness and extraordinary ability.

Phillips: I love that, ignorable and interesting. Josephine is like that, and Molly too. They’re not exceptional people, but they are forced through circumstance to take action. One reviewer once said, “Helen Phillips is a quiet subversive.” I was very flattered by that.

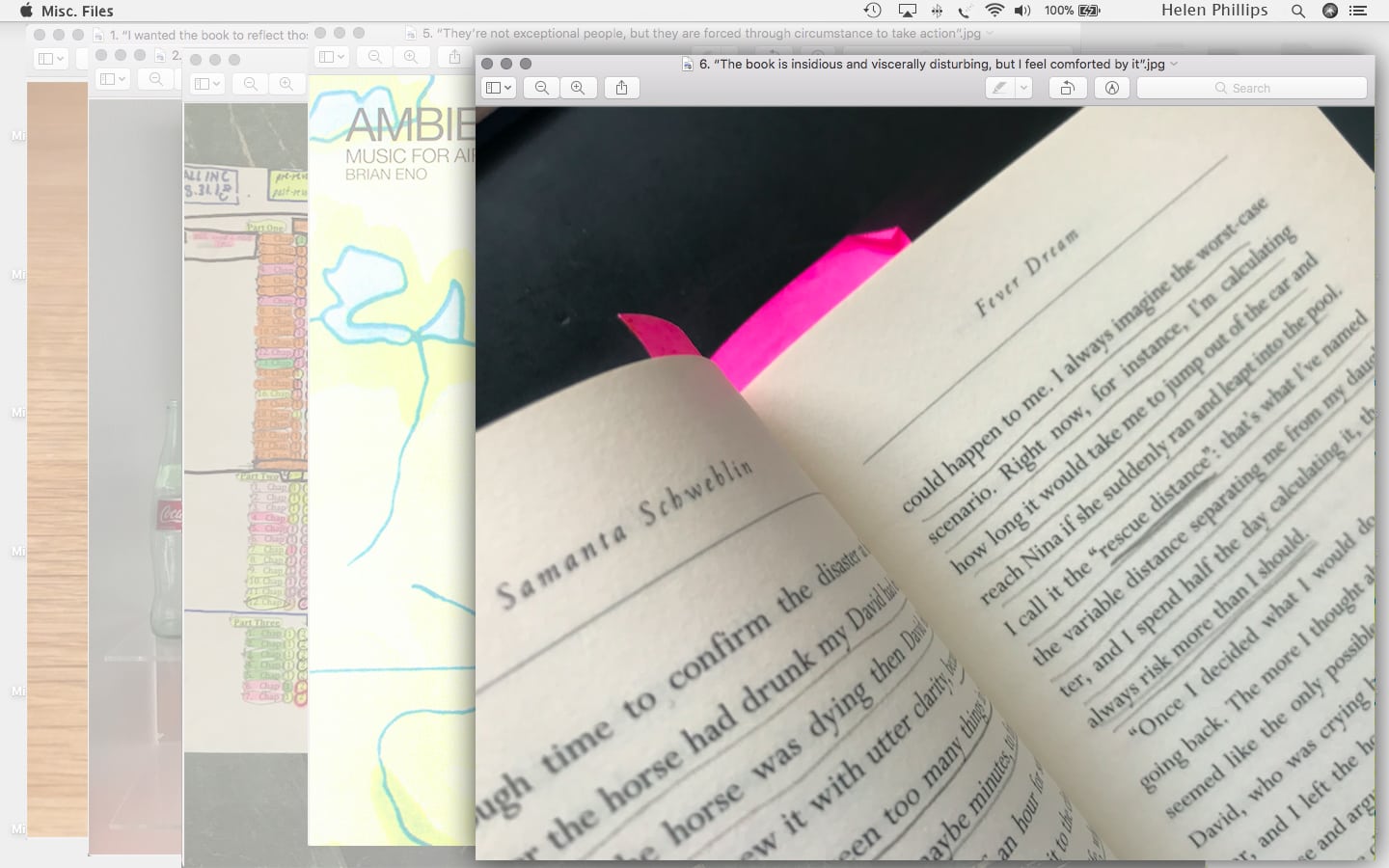

6. “The book is insidious and viscerally disturbing, but I feel comforted by it.”

Wang: The Guardian reviewed the book in this photo, Fever Dream, as following: “This is a book only parents will feel the full impact of, but that impact is so great you don’t want to recommend it to anyone with young children.”

Phillips: Someone could’ve written that about The Need!

Wang: True! What attracted you to Fever Dream?

Phillips: I couldn’t believe Samantha Schweblin didn’t have children when she wrote the book, because the way she evokes that connection between mothers and their children is so accurate. She calls it the “rescue distance”: The mother feels most comfortable when that distance is an inch, but sometimes it’s farther than that. The book has the propulsive energy of a thriller, but it also asks existential questions. It’s insidious and viscerally disturbing, but I feel comforted by it, because it makes me realize I’m not the only one who feels that way. Reading it makes me feel relieved.

I don’t know whether Schweblin agrees with this, but I also read it as a book about climate change. What you do when even the most basic things are poisoned around us? There’s a creepy feeling of an adversary you can’t identify, and a situation you’re implicated in.

Wang: A subsection of modern motherhood is very concerned about that. There are fierce discussions about the benefits of an unmedicated birth, of using cloth diapers, of using organic versions of everything.

Phillips: There are certainly questions in the little choices you make, but there’s also the big question of what the world will look like when my children are my age. Should we be bringing children into this world? I don’t know what the planet will be like when they’re old. But at the same time, having children is also the ultimate act of hope.