Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process. This particular conversation was produced in partnership with Film Forum, which is proud to present New York City’s virtual cinema premiere of Stray. You can support this vital nonprofit cinema by renting the film here.

As a result of its no-kill and no-capture policy, the city of Istanbul has a large and vibrant stray dog population that lives alongside its human inhabitants, with whom they share food, shelter, and heavily trafficked streets. At first glance, Elizabeth Lo’s debut feature Stray is a documentary that follows these dogs through their everyday urban lives. But in tracking the dogs’ journeys, and especially through her close portrayal of the golden-haired mutt Zeytin, it becomes clear that Lo is also telling a story about the power of observation: What does the world really look like from a dog’s-eye-view? What do we miss by prioritizing the human perspective over that of the non-humans among us? Is a city populated with stray animals—alongside many displaced non-citizens—a place of cruelty, or can it suggest as an alternative model of care?

Lo, who served as Stray’s director, cinematographer, and editor, shot the documentary over several months between 2017 and 2019. The re-election of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a surging feminist movement, and an influx of refugees from Syria’s civil war form the backdrop to the dogs’ daily lives. In one instance, they lead Lo’s camera to a group of Syrian boys who also live on the streets. Rather than focusing on the boys’ lack of shelter and citizenship, Lo reveals an intimacy between these two groups that both lack formal status, but have managed to make the city their home. Speaking with me from Hong Kong, where she grew up, Lo explained how Istanbul’s dogs have shaped her understanding of the city, and how Stray fits within her larger aim to tell stories that challenge both Eurocentric and human-centric ways of seeing the world.

1. “Both Euro-centrism and anthropocentrism…are equally toxic and destructive.”

Mary Wang: Why did you select this first scene?

Elizabeth Lo: This is the initial introduction to Zeytin, the canine protagonist of the film. The audience is brought into her world for the first time, and they’re asked to attach their attention to her in the same way they would to human protagonists. For the first ten minutes of the film, there’s no dialogue at all: You’re just with this dog and the minor dramas of her life. You’re being asked to step into a different time, a stray dog’s sense of time. You’re being asked to pay attention to small things, like the grass. I wish the entire film could just consist of these moments, but it has to progress eventually.

Wang: In these scenes, the viewer is asked to navigate the city in a different way. Zeytin is standing in places where humans wouldn’t stand. She’s lingering between cars and diving around hedges. How did you set up this dog’s eye view of this city?

Lo: One of the first shots you see is of Zeytin’s face. The camera then shifts onto the city, which comes back into focus. That’s basically the premise of the film: It asks, what does the world look like from a dog’s perspective? These first few shots establish the precariousness of her existence. At some point, Zeytin somehow managed to walk herself into an intersection between two highways, where she’s sort of trapped. It highlights how she lives in a world that’s very much constructed by humans. Zeytin is not human, but she’s still finding her way through our world. We don’t tend to trust dogs to navigate traffic because it’s run by very human signals. But many dogs are able to slip through these cracks of humanity and thrive.

Wang: It quickly establishes her as the opposite of pet dogs, who are often leashed precisely so they don’t run into traffic.

Lo: That’s such an underestimation of another species’ intelligence, which is what we perpetually do. These initial scenes show that dogs can do things on their own terms, even if it’s difficult and they live in a world that’s not of their creation.

Wang: You’ve talked very movingly about dogs in other interviews. Can you speak more about the history of stray dogs in Istanbul and what you’ve learned about the city’s relationship to this population?

Lo: What drew me to Turkey was learning that the Ottoman Empire, which was known for its tolerance toward many different people and religions, was also very inclusive of stray dogs. But as the empire was crumbling, a British diplomat was chased by a pack of dogs and fell to his death. The British government, in an outsized retaliation that is typical of world powers, forced the Sultan to round up all stray dogs. The Sultan had a high esteem for the dogs and didn’t want to do that, so instead of killing them, he exiled them to an island [where they eventually died of hunger]. But the people cherished the dogs, and kept a few of them against the edicts of the government, so that after these purges there would still be enough dogs to restore the stray population.

In that period, there were also French businesses that came into Istanbul and calculated how much the dogs’ fur and flesh would be worth. These companies saw the dogs as commodities instead of non-human citizens of the city, which is very typical of Western culture. Even though pets are loved, animals are defined either by a sense of property and ownership, or seen as nuisances that have to be exterminated. As a filmmaker, I’m very interested in telling stories that challenge Eurocentric ways of seeing the world. The Western point of view tends to think of cities with stray animals as immoral, inhumane. But when a city doesn’t have a stray animal population, it often means they’re all being killed behind closed doors. Eurocentrism and anthropocentrism, which puts humans at the center of the world, are equally toxic and destructive. I want this film to be an act of resistance to those narratives.

2. “The film is not trying to impose our idea of what a good story is.”

Wang: This leads us to the John Berger essay you selected. Can you talk a bit more about this text?

Lo: Personally, I love to look at animals, and I’ve always been fascinated by them. This Berger text puts words to feelings I had, the way he articulates our displacement from the natural world and what that does to our souls. We’ve always evolved with other species, but suddenly, in this modern world, that connection has been cut off. That’s why we seek out these connections through problematic institutions like zoos.

Part of the film’s premise is just to look at dogs very carefully. There’s something very profound when you, as a filmmaker or a human, see value in spending time with another life and try to see it on their terms. That’s why I try very hard in the film not to anthropomorphize. Which is difficult, because we’re all mammals, and there’s a lot of connection there.

Wang: In the essay, Berger points out that, as this distance between humans and animals increases, humans feel the need to see or portray animals through a specific frame—whether that’s a zoo or through images produced by technological advancements like cameras. I was wondering how much you conversed or argued with established conventions of depicting animals, whether from Disney movies or nature documentaries.

Lo: On a macro level, Stray has a very thin story that’s not particularly linear. It’s pretty cyclical, and there’s no real character development. It doesn’t conform to a classical storytelling structure. The film is not trying to impose our idea of what a good story is. The film ends with Zeytin alone, as she was in the beginning. That’s what I observed of her life: People come and go, but in the end, she relies on herself.

It was very important for the film to literally take on the point of view of a dog, at least in terms of height—so many animal movies seem to portray their subjects from a human height. So I wanted to create a device that would allow me to track beside them and see a world that mostly consists of human feet. I also worked with Ernst Karel, the sound designer, to distort people’s voices. The dialogue floats in and out of your attention. As humans, we’d be glued to tidbits of gossip or drama about people’s love lives. But the film always leans away from it right when you might typically lean into it, because I don’t imagine a dog would be interested in conversations about Instagram, or even women’s rights.

Wang: The most prominent human characters in the film are a group of refugee boys from Syria, who form a relationship with the dogs. The desire to “humanize” a story’s subject applies not only to animals, but to all that are perceived as “other.” It’s as if subjects have to fit into a viewer’s existing conceptual framework to be worthy of observation. What choices did you make in representing these boys?

Lo: It was Zeytin who led me to them. I found their on-and-off relationship and the warmth they found in each other very moving. To exclude it would’ve been to deny reality, as Zeytin’s life was so intertwined with that of these young men. The edits were a struggle, because we didn’t know much about their lives, even though we became so intimate with them through the camera, witnessing moments like them waking up in the morning. They have to sniff glue to cope with their living circumstances: It suppresses their appetite and makes them able to ignore the cold. There is no explanation for that in the film, but I’m also assuming that if audiences are astute enough to have sympathy for and solidarity with Zeytin, they’ll be able to extend that to these young men who so clearly loved the dogs and formed a pack with them.

Wang: The narratives of both the boys and the dogs are a refraction of the types of care that Turkish society extends to its stray citizens. They are offered some shelter, some food, and some sympathy—they are allowed to co-exist. But the support has its limits too: At some point, people move on with their own lives.

Lo: There are people who have walked away from this film feeling that the humans in it are treated far worse than the dogs. But I see warmth that permeates every level. Of course each of these populations are at different points on the spectrum of power, but I hope the film is a fair portrayal.

3. “She asked viewers to read into those surfaces—of people’s faces, of people’s clothes, of the way they waited at bus stops.”

Lo: In the clip of Stray I shared with you, there’s this shot that starts around 3:00, where you’re tracking Zeytin as she disappears behind people on park benches. You see all these people in the foreground, their faces and their gestures, just passing by. As I was editing the film, D’Est was in the back of my mind, especially the way Chantal Akerman chose to portray people and tell the story of the fall of the Soviet Union through surfaces, with no context. She asked viewers to read into those surfaces—of people’s faces, people’s clothes, the way they waited at bus stops—and trusted the power of capturing those alone.

Wang: The shot moves like a timeline, but one that doesn’t necessarily lead anywhere. I wonder how you worked with your timelines in this project—from shooting the footage over a period of two years to editing it together into some sort of chronology.

Lo: I didn’t pay much attention to the real chronology of what and when I shot, but a lot of what unfolds in the film actually does match the sequence of shooting. There’s a scene where the dogs fight over a bone and a trash man comes to intervene. Shortly afterwards, the dogs wander, a man and his daughter plays with them, but then the dogs hear a cat and wander into an alleyway, where they reunite with the Syrian boys. That sequence was actually continuously shot.

4. ”It says so much by using just non-human and ambient sounds.”

Lo: This sound piece by Ernst Karel is so beautiful, and I recommend everyone to listen to it in the dark, and if possible in surround sound. You hear the dogs of Thailand, and then a call to prayer, then the sound of fluttering pigeons piercing through the sound of traffic and the national anthem. It’s a beautiful commentary on the city, and it says so much by using just non-human and ambient sounds. I remember being very inspired by it and hoping that I could make a film in this spirit.

Based on his work and from our meetings at film festivals, I knew how much Karel cared about the fight for non-human rights, on a personal level. His sound design for Sweetgrass and Leviathan is all about how the human dialogue is secondary to, or at least equal to, the sounds of the animals and the ocean. So I always knew I wanted to work with him, and I was so thrilled when he said yes. He actually sent me a microphone that allowed me to record bidirectionally, in an organic way. We were capturing sound from all around and he had so much material to work with.

We created these moments in the film where you’re really tuned in to a different type of hearing, as an attempt to recreate what canine hearing might be like. Near the end of the clip I shared with you, you see Zeytin wander into a park and it’s suddenly silent because another dog is approaching, and all her attention is directed that way. In that moment, the ambience of the scene really changes: It becomes unfamiliar and a bit alien. Suddenly, the sound of the twigs cracking is much sharper and louder, and the city ambience thins out.

Wang: I really love the way you’ve described the sound design. I want to rewatch the whole film now so I can pay more attention to those moments.

Lo: You probably watched it on your laptop, but it was meant to be heard on a 5.1 surround system, where those differences are very pronounced. Unfortunately, that’s one of the side effects of watching this film during the pandemic.

5. “Being a foreigner in Turkey was a very comfortable position for me.”

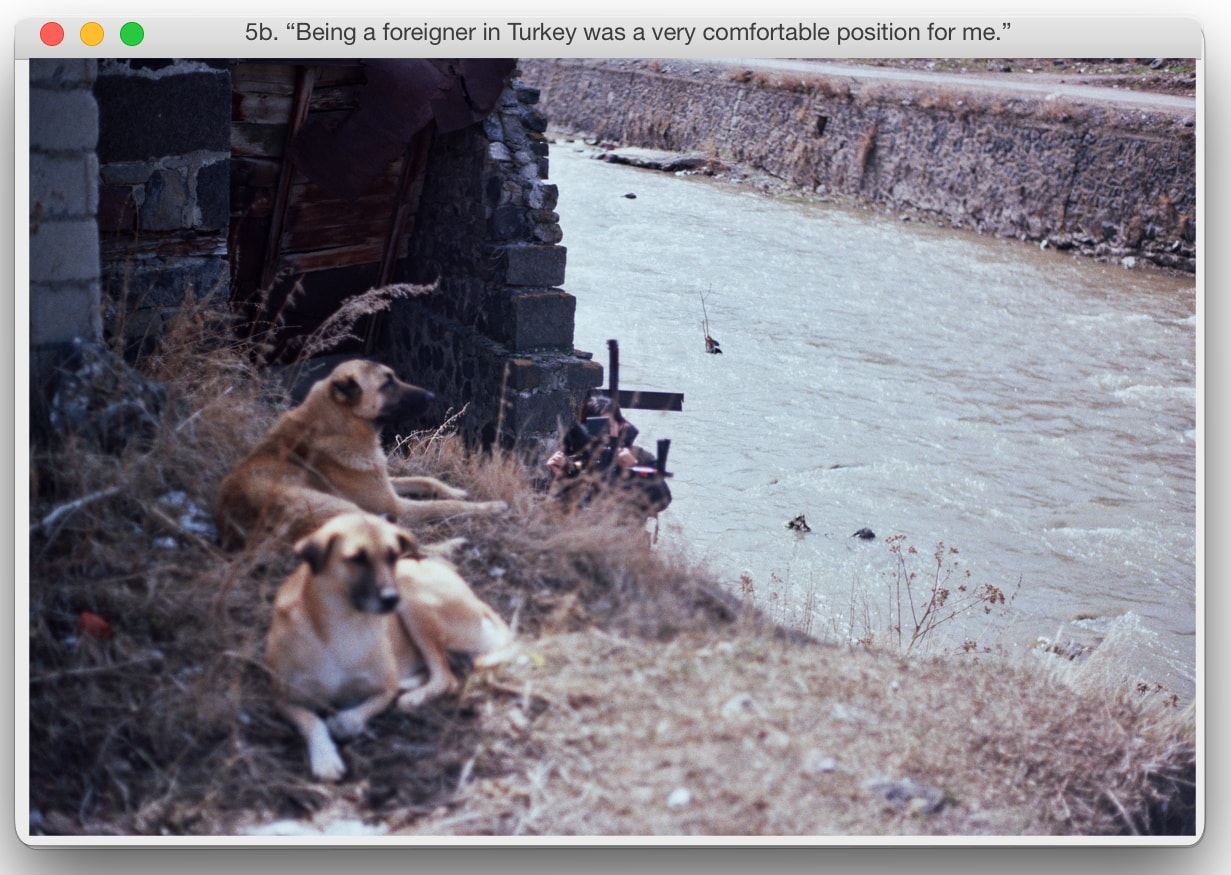

Wang: You sent some really beautiful behind-the-scenes photos, which show how you, working as your own cinematographer, were lying on floors and bending and curling yourself in different positions to get the shot. It reminded me of how, as you were shooting this, you were a stray yourself. You were being led through a city you didn’t know by an unpredictable guide.

Lo: My experience of Turkey and Istanbul is so skewed because I only know a stray dog’s preferences for where to eat and sleep! I had a terrible sense of direction, so when I followed Zeytin for the shoot, I had to completely trust the fact that she would know how to get us back to where we started. And she always would. I loved surrendering to her desires and rhythms through the city. If she took a four-hour nap in the middle of the afternoon, I would just hang out beside her. It was exhausting at times, because the stamina of dogs is pretty incredible. They go and go, in whatever direction they want. We just had to follow, chasing her around while crouched low. Throughout the film, you’ll see the camera shaking occasionally: Those were the moments I lost control or the stabilizer failed me. But it was such a joy to be enveloped in their world.

Wang: The film portrays a very distinct type of intimacy. The camera weaves in and out of human legs, getting to places where a fellow human would rarely be allowed to go.

Lo: You’re totally right about that different level of intimacy. So many times the dogs would wander into really dark and dangerous-looking alleyways, and we would just follow, trusting that the dogs would protect us. This was the case even when we were filming with the young men: I couldn’t communicate with them because I didn’t speak Turkish, but they allowed me to follow them so closely, within days of meeting them. I think that was because our focus was on the dogs, and because we shared a love for them. The dogs were so close to the young men; they would rub their faces against each other, and we would get that close, too.

Also, because I was a foreigner, people allowed me to get close to their conversations in a way that wouldn’t have happened if it had been clear that I understood what was being said. I existed in a limbo, like the dogs, where I wasn’t entirely part of human society. But it was such a privilege to be able to occupy that space and exist in this crack.

Wang: It’s interesting you say that, because I thought a lot about this part of the immigrant experience when I watched the film. Especially as a new arrival, you have the feeling of living parallel to this society you’re not entirely part of. You have very little context for things that are happening and don’t understand many of the conversations around you.

Lo: I think that, on some level, the film is indeed trying to channel this immigrant experience, the feeling of being an outsider. I showed the film in China once, and someone asked me why I like to occupy this outsider’s perspective. They very astutely pointed out that because I grew up in Hong Kong, culturally American with a Chinese-American mother, and later moved to America, I’m familiar with this experience of being an outsider. And yes, that’s probably why I’m drawn to the outsider’s gaze. Being a foreigner in Turkey was a very comfortable position for me.