Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Bunny, the writer at the center of Binnie Kirshenbaum’s latest novel, Rabbits For Food, is so singularly sharp, funny, and depressed that she’s best described through her own words.

The novel is a book-within-a-book that finds Bunny retracing, in third person, the steps that led to her breakdown. About her stalled career, she writes, “How can you expect anyone to take you seriously when, as one astute critic put it, your book jacket looks like an ad for a feminine hygiene product?” Observing her “delightful” friends, “Bunny wonders how much longer she can sit at a table with five people engaged in passionate discourse about balsamic vinegar, the answer to which turns out to be three seconds.” And finally, about her mental state: “Bunny does not want to kill herself. She does not want to die. It’s that she no longer wants to live. To not want to be alive is not the same thing as wanting to be dead. Bunny would prefer to die of natural causes, but she’s not sure she can wait it out.”

This all lands her in the psych ward of a New York hospital: a “loony bin” where the furniture is “larval,” the food “gloppy,” and the people, for lack of a better word, “crazy.” The novel is an intensive character study of a woman on the verge of a breakdown—written with distinctive relentlessness and the compassion that Kirshenbaum has cultivated for all her characters across six previous novels and a collection of short stories. It’s also something that Kirshenbaum tries to impart to her students in the creative writing MFA program at Columbia University, where she is a professor and the director of the fiction department.

Bunny fits perfectly into Kirshenbaum’s world, in which she’s imagined a cast of eccentric, unruly, and enticing women who defy easy categorization. In her novel An Almost Perfect Moment, Valentine Kessler, a Jewish girl who bears a striking resemblance to “the Blessed Virgin Mary as she appeared to Bernadette at Lourdes,” nurses a crush on her loser math teacher. The narrator of A Disturbance in One Place juggles three lovers and a husband and has one opinion about using condoms: “No one does.” When Kirshenbaum and I settled in a Greenwich Village café and talked about these women, we both recognized that they are not straightforwardly fictional—they represent the friends and allies we like to keep in our close circles, too.

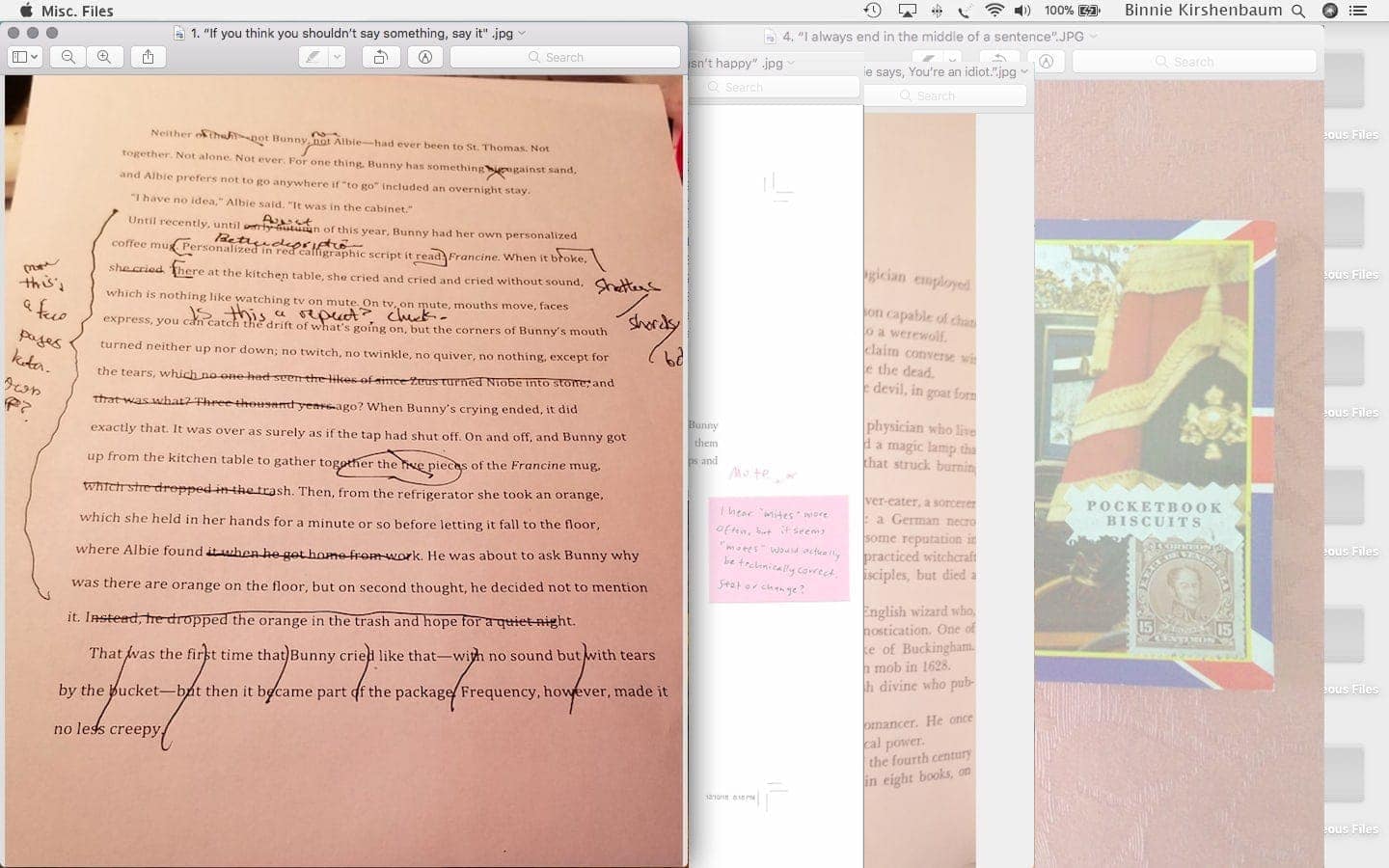

1. “If you think you shouldn’t say something, say it.”

Mary Wang: There’s a lot of crossing out on these edits. The language in Rabbits has such immediacy and urgency, which made me wonder if a lot of writing happened in the editing process.

Binnie Kirshenbaum: I write a first draft, a second draft, and then, somewhere around the fourth draft, I start line editing. I’ll start all over again with a fresh file, and I’ll write my line edits on the side and look over them. I describe it as peeling an onion.

Wang: Was there anything specific in this case that only emerged in the fourth or fifth draft?

Kirshenbaum: Part of the tone emerged later on, because I tightened up the prose a lot. It got funnier, snappier. I inserted more about the psych ward later on, and I wound up taking out a lot of the dialogue. I always tell my students: When someone says, “Hello,” and the other person says, “Hello,” and one of them says, “How are you?” and the other says, “I’m fine,” you only need to write “How are you?” on the page to imply everything. That’s something I enjoy about teaching, because I’ll tell my students something that I catch myself doing too.

Wang: Rabbits is incredibly funny. The humor is entertaining an sich, but also functions as a characterization of Bunny’s distorted mind. How does humor work for you?

Kirshenbaum: When I first start writing, I put down whatever I’m thinking of. One of my rules for writing is, if you think you shouldn’t say something, say it. I do that, and sometimes it comes out as funny, and sometimes it just comes out as obnoxious. Bunny is rough on people. It’s the kind of roughness that people think to themselves, but don’t say. But she’s mentally ill, so she will say it.

I also have a firm belief that you can’t separate comedy from tragedy. Of course, there are tragedies that don’t have comedy in them and the other way around. But when something is very painful or awkward and you just can’t take it, you laugh. That’s the way we cope with things.

Wang: You write a certain unreasonableness into your characters that is painful and attractive at the same time, particularly in your female characters. What attracts you to such that quality?

Kirshenbaum: Maybe because I’m unreasonable, ha! On a serious note, since I started writing, I’ve noticed how men write those characters all the time, and people talk about how complicated their characters are. But women characters get treated differently and get chastised for being unlikable. While I’m not a big fan of Philip Roth, I’ve studied his work a lot. He had a willingness to be not nice, and that’s what I wanted to do.

When I was younger, when I liked a boy, I would always ask him out. And people would say to me, “You can’t do that.” I would say, “If he is bothered that I asked him out, then he’s never gonna like me anyway!” I look at creating my characters with the same assertiveness, the same unwillingness to adhere to societal norms.

Wang: I’ve been reading a lot of coming-of-age books, because I’m attracted to the unreasonableness their protagonists embody. Then I realized that all characters need to embody that in a certain way, to appeal to the reader.

Kirshenbaum: I totally agree with that. I tell my students in workshop, if you look at the Western literary tradition from its very beginning, who’s just nice and happy? Who’s nice in the Bible? Who’s nice in Shakespeare? Even when you’re talking to your friends, and someone says, “I just met the nicest person,” you start to roll your eyes. Who cares? But if you say, “She was so crazy,” everybody leans in. But I do want my characters to be sympathetic. You don’t have to like them, but you have to care about them.

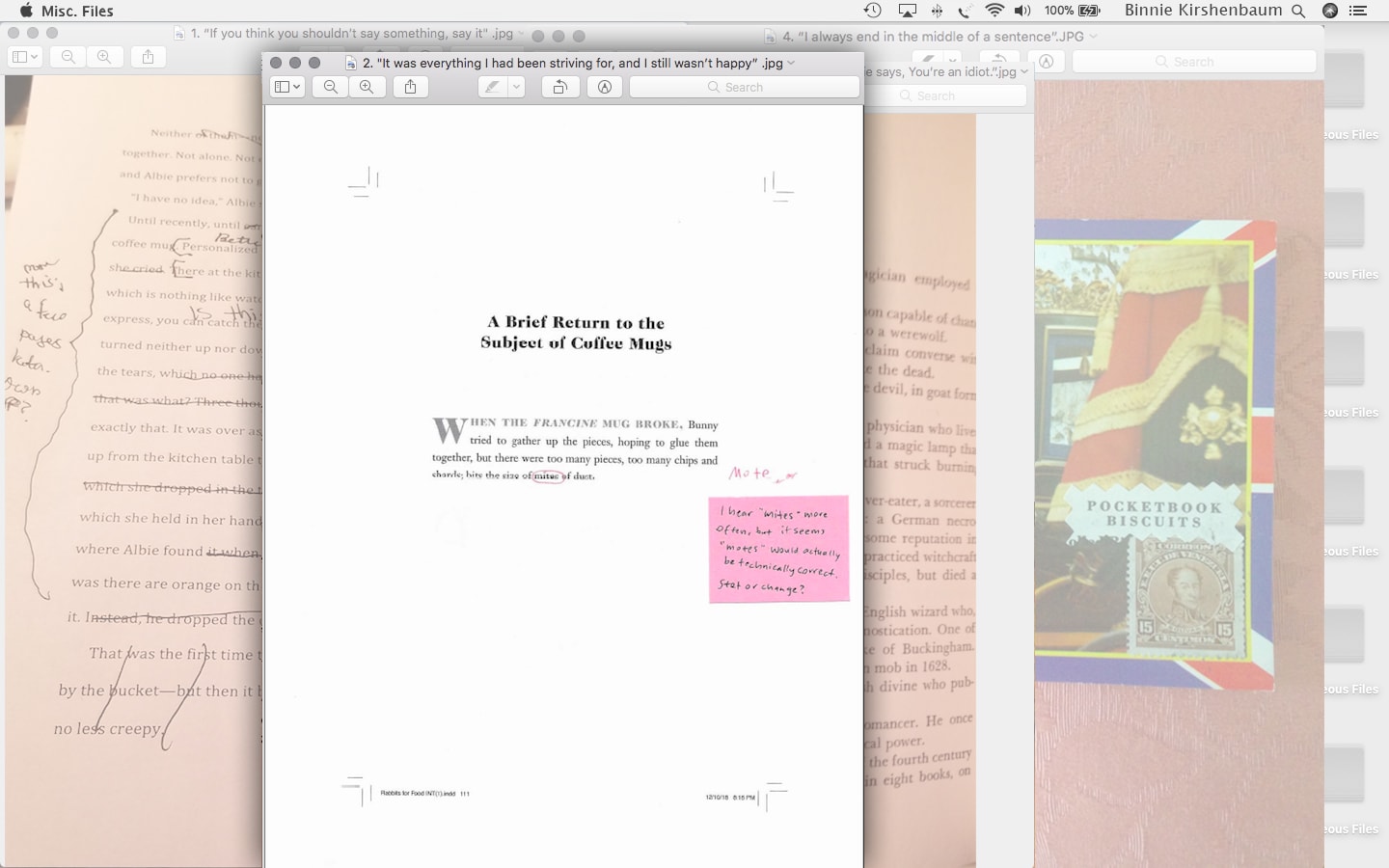

2. “It was everything I had been striving for, and I still wasn’t happy.”

Wang: You sent this PDF too. Where in the process was this?

Kirshenbaum: This is from an early draft my editor made notes on, to which I responded. It’s a few drafts further from what you saw before. They make you go through this a few times, so you go back and forth a lot.

Wang: I’m surprised you were willing to share these. Writers often feel that the editing process is too intimate to allow other people to have a look.

Kirshenbaum: Sometimes I’ll bring things like these to class, so maybe it’s part of teaching. Students have to know what it’s really like. They can’t just go out into the world and think their work will be brilliant without anything having to happen to it. In fiction workshops, a lot of students don’t want to revise something; they just want to write. But I’ll tell them that the revision is the writing. Every writer gets these; I don’t have shame about that. I want my book to be as good as I can, and I want a good editor to help me do that.

Wang: Interestingly, the only other person who shared something similar for Miscellaneous Files, Jabari Asim, is also a full-time educator.

Kirshenbaum: What I like about a writing program is that you learn how to fail and how to fix it, or how to acknowledge that something has failed. Not everything we start is going to be a book.

Wang: Do you see a lot of students worry about failure?

Kirshenbaum: I do, and I try to talk to them about my own failures. In my time as a writer, I’ve written two full novels that I’ve thrown in the garbage can, but that’s all part of the process. You can think you’ve just wasted a year of your life, but the ones I wrote after were always a lot better.

Wang: Bunny feels she’s failed in everything—in a way, she’s failed to live, which is one way to describe depression. When I interviewed Ottessa Moshfegh for this series, she said, “Depression is an intolerance to life, but it can also be profound. Maybe the trouble is that we don’t respect it enough. What if you’re actually having the most important experience of your life? I probably learned a lot more about myself, life, and God from being depressed than from anything else.” I loved the way she talked about it.

Kirshenbaum: It defines so much of your worldview and how you relate to people. People often think you did this to yourself, or that you can stop it. When I was twelve or thirteen, I experienced my first bouts of depression. My mother would then say: Let’s go shopping! But that’s not going to fix it. I first realized it was really a problem when I had published my first book, which was everything I had been striving for, and I still wasn’t happy. I realized that it didn’t have anything to do with external circumstances.

I want to take these things out of the closet. Sometimes people are surprised that I’ll talk about it. But I had cancer a few years ago, which was an illness, too. Should I also not talk about that? I’ve had students who struggle with depression come to me, and some have a terrible fear about people, or their parents, finding out. I’ll try to explain to them that it’s not their fault. Get help the same way you would if you’d broken your arm or had diabetes.

Wang: You portray Bunny’s depressive state in a very distinct way. While we can see through the eyes of other characters that she seems numb, her interiority doesn’t come across that way. If anything, her mind is incredibly sharp and quick-witted.

Kirshenbaum: Anger and depression are very closely related. When depression would start to come on, I would feel it physically. It’s infuriating, and it made me very angry at everybody around me. Some say that depression is anger turned in on yourself. That’s what Bunny is feeling. She feels numbed, but she’s also angry: at hypocrisy, at pretentiousness, at people not understanding. My editor and I talked about how the story she’s writing, which makes up the novel, is written from the hospital, which means that there’s a bit of retrospect to it. I don’t know whether she’s necessarily healthier in the hospital, but I think she at least feels safer there, since she’s around other “like-minded” people. Realizing what’s wrong with her is what allows her to write again.

But I did want her to be a very observant and honest person, who might say what others might not. There’s a part in the novel where she’s in the laundry room, and her neighbor is there with her children. The neighbor is talking about how wonderful having children is, and she’s encouraging Bunny to have her own. Bunny isn’t crazy about children, and she refers to the kids as “little shits.” Friends who read the manuscript told me to take it out because it’s too nasty. I said no, because Bunny would think of them as an annoyance. Taking that out would be to please people, and I didn’t want her to want to please anyone.

Wang: I wonder what your take is on the age-old relationship between writing and mental health. On one hand, we often say that writing shouldn’t be therapy. On the other hand, a lot of the traumas that Bunny is trying to deal with are only addressed through the writing prompts she does, like her issues with her family and the death of Stella, her best friend. When the book comes to a conclusion, Bunny starts writing again, which hints at a potential recovery.

Kirshenbaum: I don’t think writing is therapy, although for some people it can be. People can use journals to work out what they feel, for example. Bunny takes a creative writing class in the psych ward, which of course, she hates, because writing is her profession. At the same time, she has nothing else to do there, and writing is all she knows. The writing gives her a sense of purpose again and lets her reclaim what she thought she had failed at terribly.

In college, when I was depressed, I didn’t want to get help because I thought it made me a better writer. I thought that if I was no longer depressed, I would lose the darkness. And then I realized that when I’m depressed, I can’t write. It was actually when I was feeling okay that the writing acquired a greater darkness, because I felt safe going there. I’m not sure whether Bunny is better at the end of the book. The ECT didn’t do anything for her at that point. But it does allow her to connect with things she had shut off.

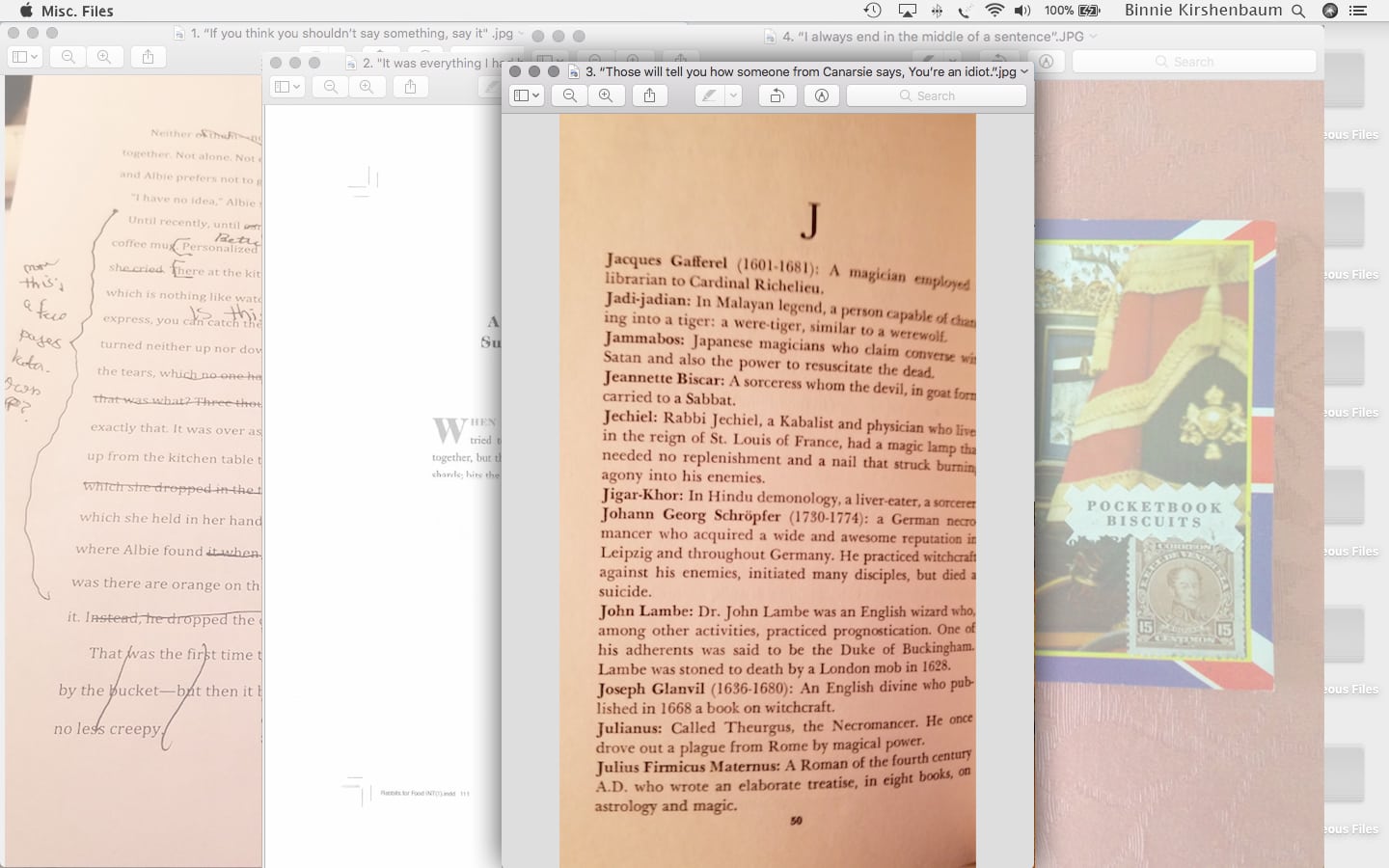

3. “Those will tell you how someone from Canarsie says: You’re an idiot.”

Wang: Do you have an ideal syllabus that you always impart to your students?

Kirshenbaum: For one of my classes, called The Dictionary, I spent a lot of time with my students studying dictionaries and thesauruses. The one here is The Dictionary of Magic (published in 1956 by Philosophical Library, Inc.) I found that students often didn’t pay much attention to their words in their revisions. Not every sentence has to have an amazing word, but you have to say what you want to say, to the best of your ability. Sometimes writers will just pick a “cool word” and use it. They feel that any word will do, but any word won’t do. For the class, we would write a sentence and then rewrite it using words from the thesaurus. Everyone also had to read two letters of the dictionary in full and talk about their discoveries. We conceived our own portmanteaus, collective nouns, and definitions for commonplace words, which isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Wang: English is not my native tongue, and I often bump into problems using the thesaurus. Even though I’m well-educated—perhaps even over-educated—it can still be difficult for me to choose words, since it’s not just about their theoretical meanings but also their culturally-specific usage.

Kirshenbaum: Always double-check with the dictionary when you choose a word. You’ll always find, not only different meanings, but other implications of the word. There are such amazing dictionaries: slang dictionaries, colloquial dictionaries, and so forth. Those will tell you how someone from Canarsie says, “You’re an idiot.” Also, it involves listening to people. How do they use words? I know a lot of people from the South, and although I don’t write from that perspective often, I know I always nail it, because I listen to people and the expressions they use.

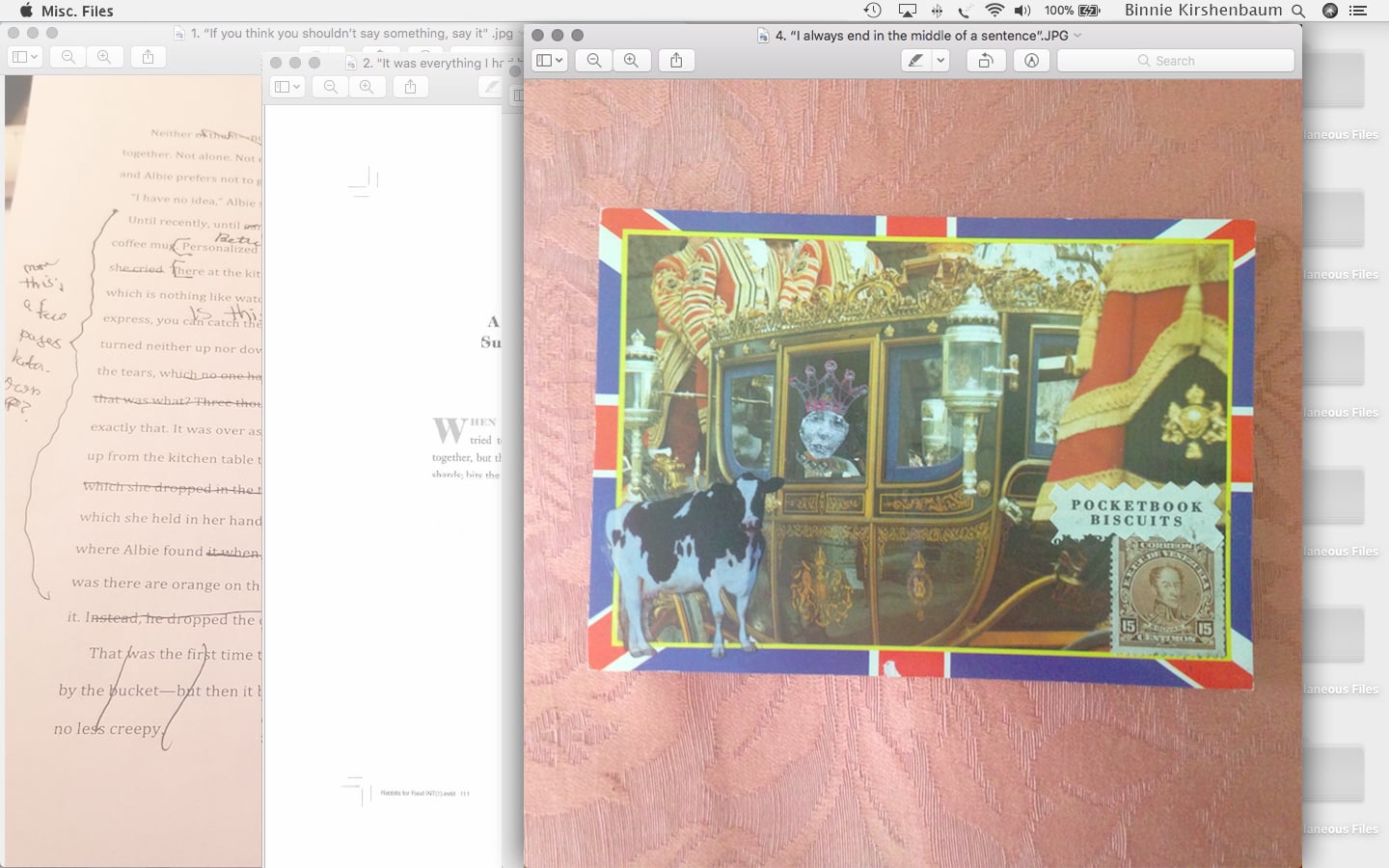

4. “I always end in the middle of a sentence.”

Wang: Before the interview, you told me about how collaging plays into your work. Can you explain how?

Kirshenbaum: It’s not that I planned to work this way, but I often start with little short pieces. For Rabbits, I only realized later that the small pieces I thought were part of the narrative actually fit into something bigger. Those pieces became the “writing prompts” dotted through the novel. I use this technique a lot in other books as well—in one I used fake diary excerpts, for example. In The Scenic Route, I had a lot of little stories inside stories, that were only tangentially related.

Wang: How did you start making these collages?

Kirshenbaum: I started doing them because I love old photography, and I was always buying old photos at thrift stores and flea markets. I didn’t know what to do with them, until this time I went to visit a friend who’d just had a baby. I didn’t have a card, so I went through my old photographs and put a baby card together. All of them were for other people, so a lot were given away. Deborah Eisenberg is a good friend. So I for the publication of her new book, I cut out a little picture of her face and stuck it in the collage I made from this postcard I had of one of the Queen’s jubilees. The ones I kept are spread around the apartment, and the ones that I like I keep in my writing space.

Wang: What are your writing habits? Have they changed throughout the years?

Kirshenbaum: Not really. I write when I get up, and I try to write five to six days a week. I discovered it’s really important for me to stay connected to it. I don’t understand writers who only write on Saturdays, for example. When I was finishing the end of this book, school became really crazy. On some days, I could only write for twenty minutes. I’ll still try to write, if only two sentences, just to stay connected. But usually it’s four to five, sometimes six hours—anything after that is a waste of time. I have different ways of easing into things, too. Sometimes I’ll say, “I’ll write a page a day, and once I have twenty pages, I’ll write two pages a day, and once I have sixty pages, I’ll write three pages a day.” And I always end in the middle of a sentence, so I can pick it up again.

Wang: You once said in an interview that place is character for you. Your novels often include journeys, and in Rabbits, the psych ward becomes a topography itself. How do you research and build this sense of place?

Kirshenbaum: Usually I write a draft or two, and only then do I start doing research. I try to spend time at a place if it’s somewhere I haven’t been, or I read about it and look at pictures. I’ve never been called out on getting it wrong, so I think I’m pretty careful about things. One of my books is set in Canarsie, for example, but I had never been there before writing.

Wang: I’m surprised by that, because the details of that book, An Almost Perfect Moment, felt so specific, almost anthropological.

Kirshenbaum: When I was in college, I worked as a counselor in a summer camp. A whole group of the counselors were from Canarsie, and they were all Jewish and Italian. That stuck, so for the first two drafts, I just made up this world. And then I visited, and I was very pleased to see that what I imagined was pretty close, even though the novel was set thirty years ago. After it came out, somebody asked me what year I graduated, because they looked for me in the Canarsie High Yearbook. And I thought to myself, thank you!