Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

When I first unboxed Deathwish, Ben Fama’s newest book of poetry, I felt like I’d signed up to be part of an exclusive club. It came with a patch and a sticker, both with the book title and Fama’s name in gothic font and two hand-drawn little cherubs—one kissing the other’s cheek—sandwiched between. It felt like a starter kit for outsiders. The book itself, which got many looks on the subway, is a bit like a biker vest, bound with a textured black matte finish, and featuring oversized silver lettering. My first thought was, Am I worthy of reading a Ben Fama book? Do I belong to the club?

As I read on, I learned that behind the tough/sexy exterior and cult allure is a brave, vulnerable body of work—one that speaks to all of us living in a world inundated with celebrity chatter, governed by social media, and contending with ever-expanding definitions of intimate relationships. In his poems, Fama explores the haziness between our real lives and the simulations that sustain them. His work solders a yearning for human connection to the faux-mysticism of consumer culture, and expresses it through clear, assured lines. Over a number of months, Fama shared screenshots and videos with me that gave me more insight into his thinking. He opened up about his workspace, his process, and who he’s really writing for.

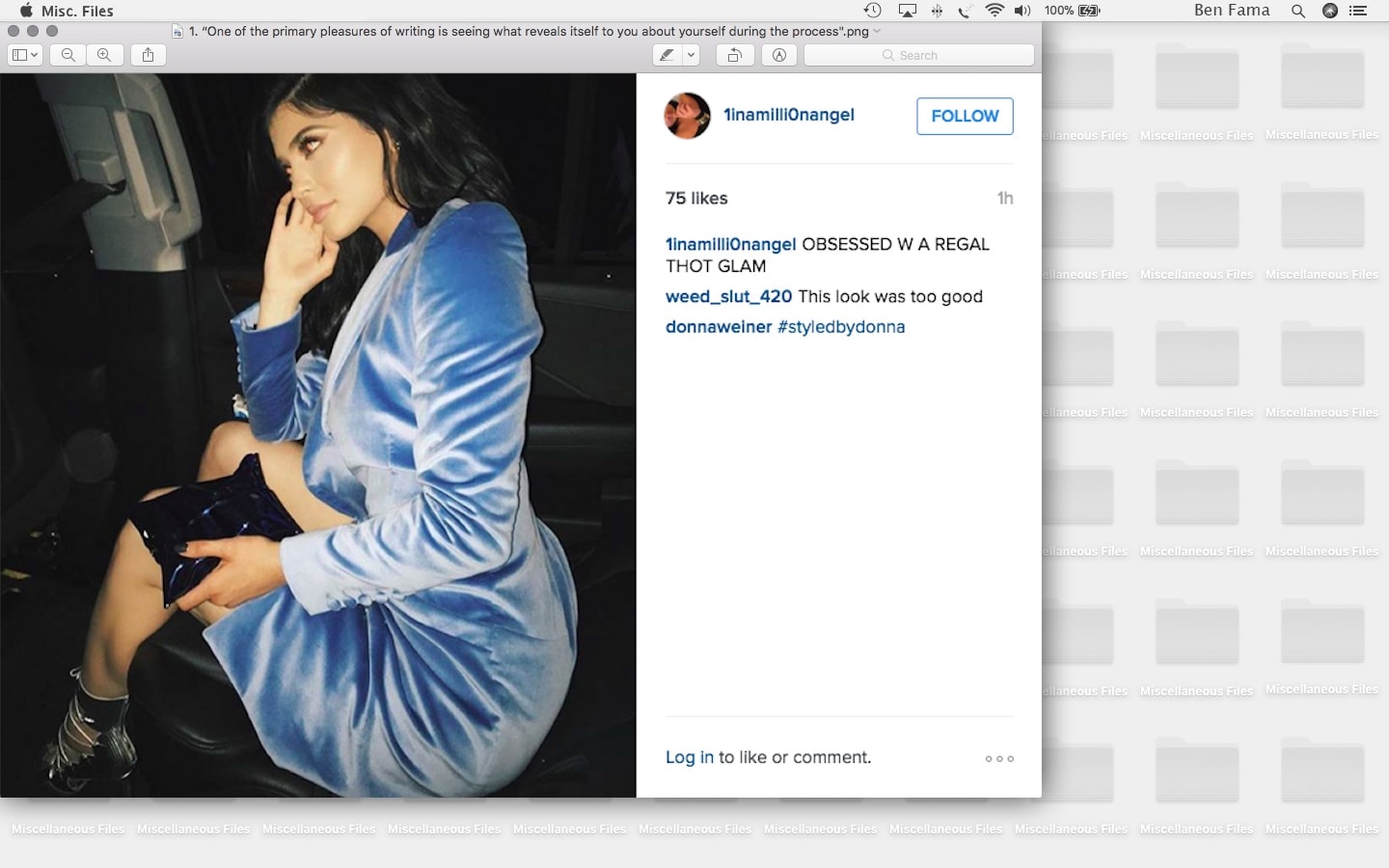

1. “One of the primary pleasures of writing is seeing what reveals itself to you about yourself during the process.”

KrisAnne Madaus:

There’s a picture on my phone

I grabbed from your feed

It’s like a repurposed masterpiece

On loan from The Frick

a one-in-a-million angel

with a hand on her cheek

From this section of your poem “1inamilli0nangel,” I gather that this screenshot is an example of you starting with an image to write. How often does that happen?

Ben Fama: Not very often! I experience the world most strongly through sight and sound, but that doesn’t always translate into a point of departure into writing.

Madaus: What’s a sight or sound that has stuck with you and affected your work?

Fama: A sound effect that has stuck with me for a bit too long is the “Smoke Monster” noise from LOST. [The noise of sirens] is everywhere here in NYC. Sound isn’t overdetermined in my writing as much as it might be in other poetry. However, there is one poem in Deathwish called “Brat’s Lullaby” that is meant to be read aloud in order for the meaning to truly arrive.

Madaus: How do you collect these things before you sit down to write? Where are they all stored? What hurtles you into motion?

Fama: Sarah Schulman discussed what she believed a writer wants more than anything: To think that someone cares about what they are writing, that it means something to the people at the heart of their work. That’s my answer too. As far as storing things goes, they are (innocently? unconsciously?) stored in the image bank of my mind. One of the primary pleasures of writing is seeing what reveals itself to you about yourself during the process.

2. “My mind is not much of an ally, unfortunately.”

Madaus: So, your brain filters your material for you and whatever keeps bubbling up in your mind must hold some sort of significance. What about teddy bears? Why do they keep bubbling up on Instagram and elsewhere? What do they mean and does it hurt them when you stitch your Deathwish patches onto them?

Fama: My mind is not much of an ally, unfortunately. It’s an unfriendly place! The bears are a nod to Evelyn Waugh, who famously included a teddy bear in his novel Brideshead Revisited. They loved the pain play.

Madaus: How so? What sorts of blocks do you experience and what do you do to overcome them?

Fama: Think of a “bad trip.” If there is something that can give you a bad trip, it gives me one. I prefer to dissociate!

3. “Fiction is like a dysfunctional family vacation where you returned tapped out of mental strength, the kind of vacation where you need a vacation to recover afterwards.”

Madaus: Another influence in your work seems to be celebrity culture—you’ve included Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon documentary here. He says today’s Hollywood doesn’t measure up to the scandals of yore. What say you?

Fama: I think today’s scandals definitely live up to and even supercede the scandals he wrote about (and he often lied—he perpetuated a lot of bad gossip). We have scientology, sex cults, and even college admissions scandals! Paul Walker could be our James Dean—I could dig up many badly-behaved blondes—life is still everything he would have wanted.

Madaus: Where were you when Paul Walker died?

Fama: I was upstate and I had just woken up from a particularly rowdy night, so the melancholy morning became much more solemn.

Madaus: I wasn’t sure if your poem was a true memory or not. Young Hollywood is fascinating and often very sad.

We heard Paul Walker has

died. The breeze carries sweet, hot air down from the far off mountains

through grapevines, to where I am standing.

I’m curious about what you spend your time watching and what your Netflix algorithm is like.

Fama: My Netflix is pretty unremarkable because I don’t watch it much. I think I last signed on because Personal Shopper is on there. That’s my kind of film.

Madaus: Where the girl thinks she’s a medium. She discovers Hilma af Klint in this film as well. Are you interested in spiritualism? If so, how do you think it manifests in your work?

Fama: Spirituality in America—big topic…and big shadow? It seems to be a mix of Christianity and Positive Thinking, which today usually looks like corporate self-help mysticism. We’re in the era of Headspace Apps and subway meditations.

My spiritualism manifests in the way I conduct myself in relationships. In Sarah Schulman’s really great book Conflict is Not Abuse, she claims “relationships of all kinds are the centerpiece of healing.” I think, how do I approach the other in regards to how I want? I’ve occupied myself a lot of with this contemplation.

Madaus: A lot of these poems seem very personal. Who do you write for?

Fama: The devil on my shoulder, constantly daring me to try and pull it off. I was also writing for my—I can just say it—“polycule” that I was involved with. I still am, in various but different ways. We’re all writers and we were writing erotica for each other (and unsurprisingly, a lot of apology texts). I’m learning to be an ethical slut, not a messy slut.

Madaus: Why are ethical relationships so important to you personally, and what does “ethical” really mean?

Fama: Put very briefly, I think ethics is an ideal we can sort of picture, and there is the lived attempt, and the work is where you end up. An ethical relationship would have a lot of communication, mature de-escalation practices, and normative interpersonal challenges. I think it is important to me because relationships of all kinds are important to me, and I’m feeling run-down by being the same ol’ person making the same ol’ mistakes, as they say.

Madaus: Going back to polycules, don’t you wish there was a sexier term? You also practice nonmonogamy in your writing. You said you cheat on your novel with your poetry. What’s happening with the novel? And how does the way you approach poetry differ from fiction?

Fama: Poetry is like a fun day-trip out of town. Fiction is like a dysfunctional family vacation where you returned tapped out of mental strength, the kind of vacation where you need a vacation to recover afterwards. Though I have two friends editing poetry manuscripts that are under contract for publication, and they are emotionally in tatters.

As far as sexy words for things, I think it’s good that “polycule” is an ugly word. There’s a line in my book, “the body persists long after the words / that make it desirable have been used up.” Life begins once its valorization ends. Getting into the work of ethical relationships, care of the self, harm reduction, these practices are usually at odds with the current optics of social media. To accept that is to set yourself free.

Madaus: Yeah, it’s important to reflect on what kinds of messages the words we use to represent things are sending out into the world. I often think about how violent words like “slay” are used to mean success. Doesn’t mean I’m not listening to Beyoncé. I just think we don’t pay close attention to anything. Just scrolling through. I feel like there’s a growing disdain for certain social media platforms. What are your predictions for the future? You’re not someone who abstains from social media. What do you get from it?

Fama: The iPhone is truly an ideological plague! It’s a machine for revenue streams right in your hand. These social media…what do they do? Complicate “discourse” by bringing out the worst of our human character defects and keeping us hooked with these fast-coming satisfactions. The truth of social media is one of economic determinism: it is just another way for a small group of self-interested people to make more money off of us.

Madaus: Why do you participate? What do you get out of it?

Fama: I’ve been trying to be more conscious of how I use it. I’m not monitoring my screen time or anything, but I am not perpetuating aggression online. Most posts anywhere seem to be either aggressive or passive-aggressive. I’m trying to tamp it down, personally. It goes a long way for my everyday demeanor. More headspace to think about poetry, haha. Instead of fighting on Twitter, I am thinking about Aaron Kunin’s book Three Loves.

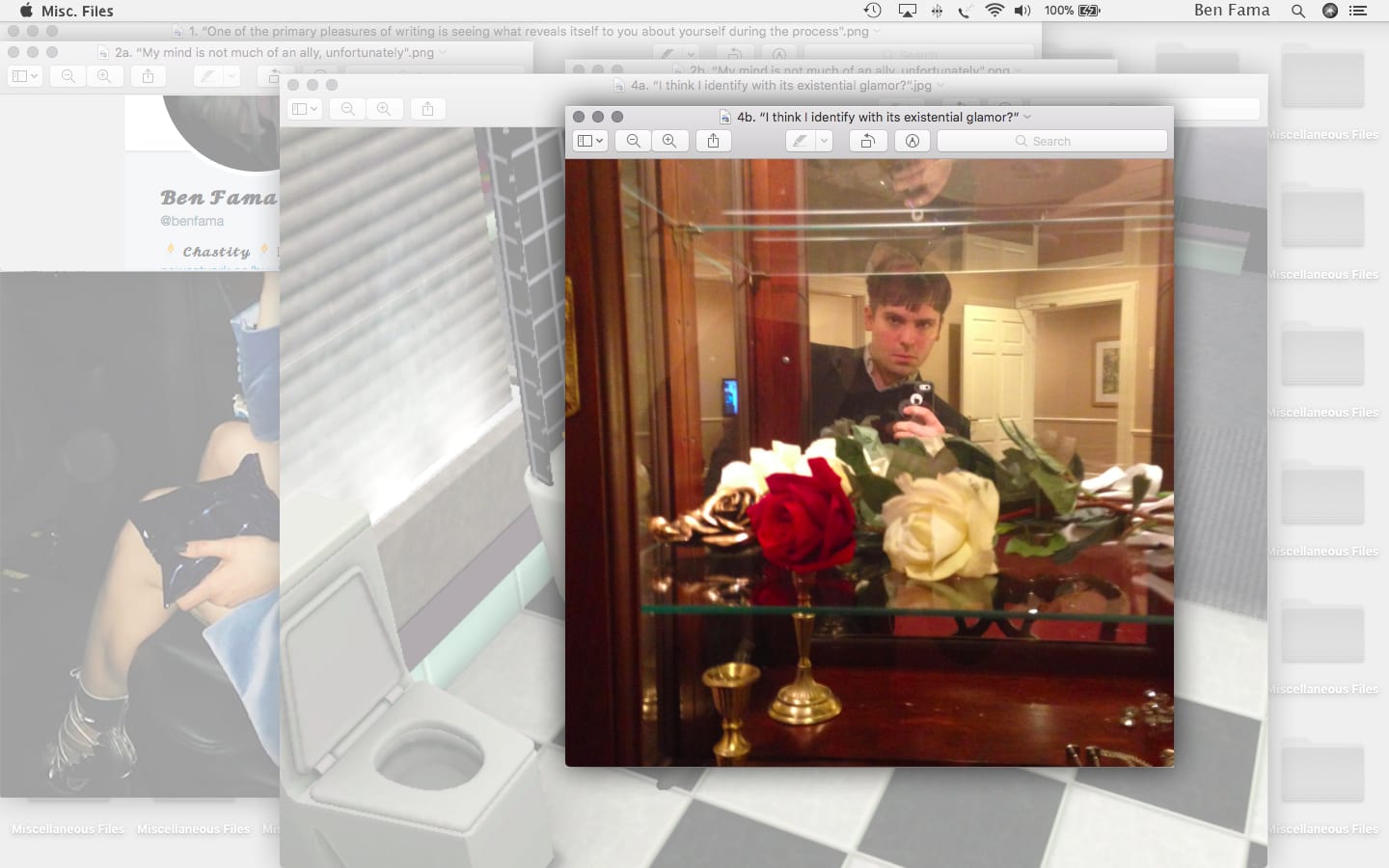

4. “I think I identify with its existential glamor?”

Madaus: And finally, you sent along this sad man sitting in the bathroom, avoiding the party. Why did you include this?

Fama: This is an image leftover from the Tumblr years that I’ve kept nearby…it’s from The Sims. I think I identify with its existential glamor?

Madaus: How so?

Fama: The maligned “funeral selfie” [below] says it all.