Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

When Anne Helen Petersen’s article on millennial burnout dropped on Buzzfeed in early January 2019, it immediately sent shockwaves through the Twittersphere, and eventually the wider internet. As a journalist and former academic, Petersen has a knack for looking critically at, yet writing colloquially about, cultural phenomena—getting at the larger trends, truths, and impacts of things like MLMs or the Chip and Joanna Gaines effect. Her burnout article was the apex of that: A breakdown of our collective breakdowns, our fatigue and paralysis and the low-lying and constant existential dread that we knew wasn’t exactly normal but had come to feel so, and why a whole generation was feeling so deeply left behind. My friends and I talked about it in frenzied tones on Gchat and Slack, and after a few days even those who weren’t “very online” had read it. It was a truth bomb, the kind of thing you read and think: Holy shit, and yes, and finally. Among friends and peers there was a sense that finally someone had given words to what we were all feeling. Finally, someone had told us we were not alone. Finally, someone saw us.

That blockbuster piece was followed by related deep-dives (Petersen on burnout across backgrounds and student loan debt; Tiana Clarke on Black burnout) and so much discourse that Petersen ended up on a mini press tour about burnout which for her sparked… more burnout. For the first half of 2019, everyone around me was talking about how sick and tired we all were, and trying to remedy it—mostly through “self-care.” But the problem wasn’t that we were individually overworked or that we needed to take a vacation. It was, and is, that our political and economic systems have been scrubbed of the safety nets that had protected generations before us (notably those pre-boomer) from such deep exhaustion and futile scrambling; ironically, it was our parents’ generation who’d done the damage. This is the subject of Can’t Even, Petersen’s phenomenal, finally-here book. And once you’ve read it, I can promise, you will be very angry.

You will also feel very seen. I read the book twice this year and both times felt a sense of rage at those who set us up for this, alternating with pity and empathy for my generational peers—some 100 of whom appear in Can’t Even. But the true strength of the book lies in the context and background it provides. Petersen outlines why “Our Burnt Out Parents” (as she memorably calls boomers) put us in this place; how they suffered their own instabilities and, in a frantic grab to hold on to middle class status, “pulled up the ladder” on the safeguards that had allowed Americans before them to get to places of comfort, not realizing it would destabilize the lives of their children.

I spoke to Petersen in mid-September via Facetime, both of us besieged by smoke from the wildfires raging across the west coast—her on Lumi Island in Washington, where she had gone for a writing retreat with her dogs, and me in hot, hazy Orange County. We discussed the book’s influences, her writing process, beloved memes, and why, yes, she does blame boomers.

1. “So many people told me that the process felt really therapeutic.”

Mickie Meinhardt: How did you start to think about writing Can’t Even and the piece that led to it?

Anne Helen Petersen: My training as a writer and as a thinker is this hybrid of first-person nonfiction essay I learned over the course of high school and college and my training as an academic, which helps me go to the history, the context. So when I first started talking to people about what I called my “errand paralysis,” I started trying to find academic explanations, which led me to realize that it was burnout. It’s a form of burnout that may not be the form I’d always heard described—a collapse, something that happens to doctors and war correspondents. It’s just become a backdrop of my life and of so many people’s lives. So I developed a framework for millennial burnout and placed it over my life, which became the original essay. When I decided to write the book, I needed to place the framework on other people’s lives but also to try to historicize it.

Meinhardt: You cast a wide net. Was that daunting to try to drill down on?

Petersen: I ordered every single book I could think of, truly 100 books. I started with economic and child-rearing history and then looked in the index and found others I should read, and so on. I don’t think it was ever daunting; this is how I research as an academic. I try to consume all of it and take all these notes in Scrivener, and then a route starts to emerge. I outline and go from there. I can keep writing forever, but I know how to stop myself.

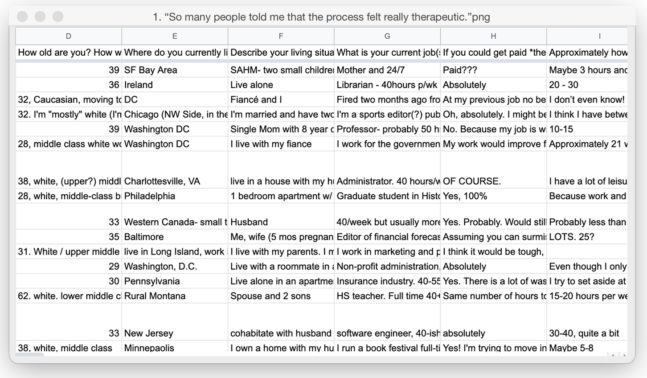

Meinhardt: Let’s start with the survey and your sourcing process.

Petersen: Since becoming a journalist, my frameworks have become much more contingent on reporting, which, unless you’re an anthropologist, most academics don’t do a whole lot of. In order to get the breadth of experiences I needed to speak to, I needed to cast a really wide net. Oftentimes [surveys are] the way to find a certain amount of people and schedule it in a way that’s tenable. Let’s say there are 100 interviews in the book. I would probably need to do at least 200 to get that, if not more, and I just did not have the timeline to do that. I’d also had good experiences with gathering stories from people using Google Forms. A lot of people, especially millennials, are reluctant to get on the phone. But they’re really into spending some time on a Google Form. There is space to write a sentence, or an entire page. So many people told me that the process felt really therapeutic; they didn’t care if it got used, it just felt valuable to them to think back on their childhood, or surveillance in the workplace, or the division of labor in parenting.

Meinhardt: It was probably the first time many of them were asked about it.

Petersen: Totally. We talk around it but not directly about it. Unless you have a really good therapist.

Meinhardt: And even then sometimes you might not! How many responses did you get?

Petersen: More than 10,000.

Meinhardt: How do you sift through that and decide whose story to tell?

Petersen: It displays as an Excel doc, so you can read pretty quickly. I read every single response, but if I got to a part of the writing process and needed someone who brought up the word “optimization” without prompting, I could do CTRL+F and find the responses that use that word and how each described self-optimization in a different way. I oftentimes am a bit defensive about it. Like, somehow, because it’s not as arduous, it’s worse.

Meinhardt: This is what the book addresses; it’s a different way to work, but there’s the idea that if you’re not working boots on the ground, it’s less valid. And of course that’s not true.

Petersen: Yes! I could’ve worked really hard, but had it not be as good a book because I spent so much time trying to cultivate those interviews. My timeline was my timeline—how could I make the best book with that, how could I include the most perspectives. And I tried to de-center my experience and the white bourgeoisie, too, to get at the tapestry of experience.

Meinhardt: When did you see patterns start to come together?

Petersen: They were just there. In my research, in the emails—there were probably 3000 responses to that original essay. A lot of people prefaced it with “Feel no need to respond but—here’s 5000 words of my personal experience”; “I’ve never written back to an author before but I felt really compelled.” And I think that especially was therapeutic for people because they were trying to process what they were going through. Hitting send didn’t matter.

2. “When you’re scared of economic instability, it leads you to embrace all sorts of things.”

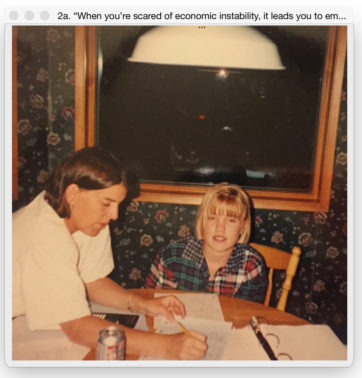

Meinhardt: Can you tell me about these photos of you, which you labeled “Idaho Childhood” and “Concerted Cultivation”? Do you think kids today will miss out on unstructured childhood?

Petersen: I chose that first picture in particular because we were camping, and my parents let me go down to the lake by myself to fish. I got one on the line and didn’t know what I was doing. Some adult down at the lake helped me reel it in. I have this visceral memory of being nervous and scared because I was very shy, so this adult coming to help me was very nerve-wracking. But at the same time you can see on my face that I’m so proud. I do not think that my friends who are parents now, amazing parents, would let their kids go fish with a fish hook at age six.

I talk in the book about how I had this blend of a really unsupervised childhood, but with my mom helping me with my math homework in 4th grade. Having a mom who would sit down with you every night and help you is something that has become more and more of a standard of good parenting. Even if most parents can’t provide it. And that was not necessarily always the case.

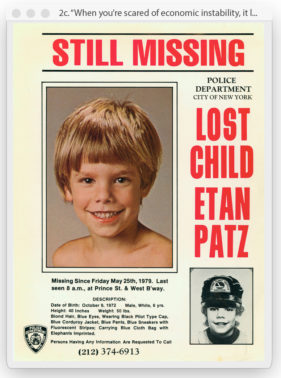

Meinhardt: That’s a good lead-in to the Etan Patz image, which evokes a push to a less unsupervised childhood.

Petersen: I wanted to have a text that re-introduced me to the idea of anxiety over unsupervised children and stranger danger, and situates that in a larger societal panic that wasn’t necessarily merited. The interesting thing about that period was that child abductions did not go up, and the person most likely in every childhood abduction remains a member of the family, usually a non-custodial parent. But the milk carton kids that developed during that period, and the made-for-TV movies about Etan Patz and others, could create enough anxiety to fundamentally change our ideas about how much supervision a child should have at all times.

Meinhardt: And that gives us an earlier exposure to anxiety as kids.

Petersen: And when you’re supervised all the time, you don’t learn your own boundaries. You don’t figure things out on your own. That autonomy is so important to developing personality and confidence. I’m not a psychologist, but I do think there are connections between our levels of anxiety as adults and how much time we did or did not have to develop our own senses of self.

Meinhardt: Has that bled into Gen Z at all? I think about the memes about Gen Z that say they do all this activism and have nothing but a latte until 4pm but are too afraid to call the doctor’s office.

Petersen: Some of the things about Gen Z are millennial traits blown up, almost caricatures—though we didn’t do as much activism because we were convinced the world was okay, for a little bit. They’re experimenting with independence online, but I think some of them don’t even have that. I think we’re too early to figure out what’s going on with Gen Z. A lot of the worst things that were said about millennials were said when they were the age Gen Z is now.

Meinhardt: Speaking of generations, let’s talk about yuppies. Millennials are the age where they’re entering our version of yuppies.

Petersen: That happened a while ago. Barbara Ehrenreich talks about the yuppie strategy in her book Fear of Falling, which I found to be the most useful text for deciphering what was going on with boomers; why they behaved the way they did in terms of voting habits, parenting habits, college decisions. When you’re scared of economic instability, it leads you to embrace all sorts of things. It’s something we talk about all the time with Trump voters, even though it doesn’t excuse the fact that they also embrace racism. The yuppie strategy was an evacuation of morals and an embrace of sundried tomatoes, and other consumption patterns in that performance of middle-classness. You can see how, as millennials, we are adopting some of them. It also functions as a skeleton key to why boomers are the way they are.

Meinhardt: The American cult of individuality does come out when you have economic instability, and the yuppies did that. I think it’s something millennials disavow, yet they also find that there’s something to looking out for yourself. But they’re too aware of everything that’s going on to only focus on themselves. That leads to its own kind of anxiety.

Petersen: I think we understand it’s shitty to focus just on yourself and your family. At the same time, when you’re so scared because of COVID, or financial insecurity, or that your kids won’t have what you had, it leads to people adopting all sorts of behaviors they might not have otherwise.

3. “They’re struggling to make ends meet, even if they’re not suffering from over-Slack.”

Meinhardt: Okay, let’s talk about Old Economy Steve. It’s so funny, of course, but I felt your book wasn’t super interested in placing blame for burnout, other than perhaps on the system itself. But there is a persistent idea among millennials that we do blame boomers.

Petersen: Well, I blame boomers! I think boomers made a lot of the decisions, voting decisions, different politicians being elected, the vilification of unions, because they were burnt out. A previous iteration of burnout: They had class instability and wanted to somehow preserve their place. A lot of Trump voters are middle or working class and want to either restore or sustain their place in the middle class. And they excuse all sorts of decisions in that goal. I can understand more why the boomers brought up the safety net, like “Here we go, nothing for you!” But it’s difficult to understand that they didn’t see how the decisions they made in terms of voting or ideology made it difficult for their kids to find that stability.

Meinhardt: They still have a hard time acknowledging that.

Petersen: Because you’re defensive about your generation. People are slow as they age to admit that things have changed. I’ve written about student debt and still get emails from boomers saying that they worked their way through college at a state school, so you should be able to do that too.

Meinhardt: That’s the #1 Old Economy Steve meme. “Paid his way through school, school cost $400.”

Petersen: We massively defunded state education! And hopefully this book gives millennials tools to have better conversations about their anger with boomers. If we just use things like “you pulled the ladder up” or “you’re a sociopath” that shuts down conversation. In the same way a lot of millennials told me they sent the original article to their parents to try to have them understand what they’re going through. A lot of parents ended up emailing me, saying they now understood their kid.

Meinhardt: I did send the original piece to my mom, my dad, my aunt, and even my grandparents. The interesting thing was my grandparents immediately felt bad that many in my generation might never own a home—they were really upset about that! But my aunt and my dad got defensive.

Petersen: How old are your grandparents?

Meinhardt: 92 and 87.

Petersen: Wow. And your parents?

Meinhardt: My dad is 61. My mom passed away earlier this year, but she was also 61.

Petersen: First of all, I’m sorry. If my grandparents were still alive they would be that age. Post-war, the middle class dream expanded to them. And that is what my parents grew up in, in the suburbs of Minneapolis. That lasted just long enough, but it couldn’t last forever. That your grandparents pitied you is in some ways appropriate, because they endured so much, the Depression, World War II, and they came home and were rewarded. Even as downturns happened, they were far enough along that for most of the Greatest Generation, they were fine. When my granddad died, he had hardly dipped into his savings, having lived just off of his pension. And he was just an accountant, not a rich person in any capacity. But I do think because boomers had to adopt these defense mechanisms to maintain what our grandparents had achieved, they do get defensive: “We were burnt out too, we were trying to maintain our class position.” Though they would never say it like that, they are very class conscious. It’s important for us to acknowledge that they were burnt out. With the book, I’m not denying that any other generation was burnt out, but that all the forces and timing have accumulated on us as a generation. The difference is that we entered adulthood during the recession, and that many millennials are experiencing parenthood during the pandemic. That timing is going to be very influential.

Meinhardt: The demographics of your responses seem pretty diverse, but I felt the most kinship in thinking of my friends in more urban areas. This book is definitely for them. I grew up in a tiny beach town in Maryland, and a lot of my hometown friends haven’t experienced this quite as much. They mostly own homes. They’re mostly married. They’ve had debt, of course, but are pretty financially stable. Does this feel more specific to urban millennials?

Petersen: The peak millennial burnout experience is probably shared by people who went to college, work in jobs that are competitive, and feel more of that formative pressure. I don’t think that competition necessarily has to be in an urban space, though. It could be in the space of your church. There is a lot of performance and toxicity online for my friends in my small town in Idaho. They’re maybe performing for a different set of people than I’m performing for, but they’re still conscious of it, whether that’s in the form of how you do your baby announcement or gender reveal party or that sort of thing. For a lot of them, home ownership is something they can achieve, but their work isn’t as stable, or they’re just worried about the future, or someone in their family is struggling. That’s universal. I do think a lot of people I talked to are suburban and urban; there aren’t a ton of people, millennials in particular, who live in very rural areas anymore. Maybe that’s going to change, with COVID-19 in particular.

People in Missoula, where I live, are way less burnt out than I am. People say, “No one moves to Missoula to work.” I try to think about that: “No, you didn’t move here to work all the time!” People are more balanced in terms of actual work hours, but, at the same time, the median salary is very low. They’re struggling to make ends meet, even if they’re not suffering from over-Slack or performing on Instagram.

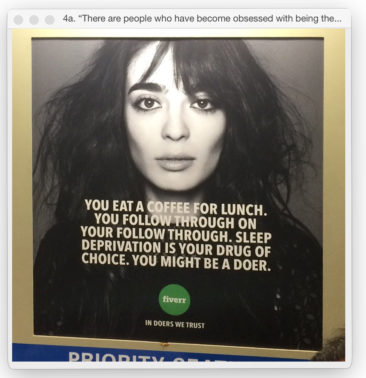

4. “There are people who have become obsessed with being the best.”

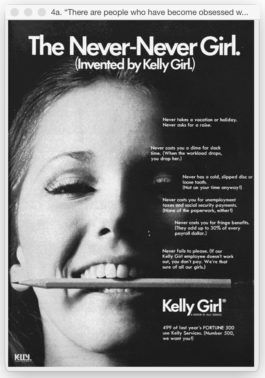

Meinhardt: The last two things I want to talk about are the Kelly girl ad and the Fivrr ad, which are connected. Seeing the Kelly girl ad, I had a visceral reaction, realizing that this is what we’re still doing. Company after company has cut jobs and brought in temps.

Petersen: How do you get rid of the people you have to treat like workers and replace them with people you don’t have to treat like workers? There is a straight line between the Kelly girl temp and the freelancer who’s on Fivrr, who is potentially fetishizing the ability to not be treated like a worker. And the temp agency really only started in the 1960s. The Kelly girl ad was in circulation through the 1960s and 1970s.

Meinhardt: Do you remember seeing that Fivrr ad?

Petersen: I do, and I think Jia Tolentino put a lot of those feelings about hustle culture into words. That was really valuable, because a lot of us who saw that campaign were like, “Wait a second, you’re saying the quiet part out loud?” We got used to suggesting that that’s the sort of culture we glorify, without putting it so baldly.

Meinhardt: I’m someone who never wants to work like that; I love work-life balance. But reading Can’t Even, there are so many people—especially when you spoke to people in the finance sector or consulting—who thought that [the Fivrr ad] is who they want to be. Do you think that ad and other things like it have contributed to warping our mentality?

Petersen: Yes! There are people like us who think it’s fucked up, but there are others who aren’t putting a critical lens on it. So it just wafts over you and that ideology becomes normalized. Thinking about someone who loves working all the time, I think it’s less “I love having little self outside of work” and more that they love winning. There are people who have become obsessed with being the best. And not because they love banking or consulting, but because they are addicted to that stability, which they can’t find unless they work all the time. I do think we could find it if we inject stability through other means. Through a safety net, or through Universal Basic Income. You allow people to do things that are nourishing to them, to their communities, that are better or more innovative for society.

Meinhardt: And you’d have less people who are in the office all the time, for whom work is their nexus. I always think, don’t you want more? A job isn’t who you are.

Petersen: A lot of people don’t have that. Sometimes that’s because they were trained to become mini-adults: they get into high school and college and a job, and they don’t know anything else other than how they can work all the time. They don’t know what being happy is, they don’t have that space, they don’t know who they are. And so you get millennials in crisis, existential or anxiety, because what else is there but my ability to work?