Perched on Monte alle Croci, a hill just south of the Arno with sprawling views of Florence below and the Pistoian Apennines and Apuans due north, sits the Basilica of San Miniato. The church, which was built in three stages from 1018 to 1207, is more quietly stunning than Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce and the Duomo; it is also older than these popular Florentine basilicas. Olivetan monks look after the San Miniato complex, which includes the church, a monastery, a bishop’s palace, a bell tower, and a cemetery. I have visited San Miniato often over the past several months, but have caught sight of the white-robed Olivetans only a handful of times and usually behind the raised counter of the little gift shop where they sell the elixirs, unguents, teas, honeys, and other products they make. Sometimes, as I walk the many steps that lead to the church, I imagine a lone monk peering at me sight unseen through the barred windows of the monastery that sits brown and heavy next to the church’s luminous white and green marble facade. He knows I will enter the church and sit in a pew set on the right side of the nave, the only place in this exquisite, thronged city where I can think clearly—or not at all, it is difficult to say which. The church is often empty in the morning and that’s when I like to walk from my apartment in the Oltrarno east along the river into the San Niccolò neighborhood and up the hill to San Miniato.

Perched on Monte alle Croci, a hill just south of the Arno with sprawling views of Florence below and the Pistoian Apennines and Apuans due north, sits the Basilica of San Miniato. The church, which was built in three stages from 1018 to 1207, is more quietly stunning than Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce and the Duomo; it is also older than these popular Florentine basilicas. Olivetan monks look after the San Miniato complex, which includes the church, a monastery, a bishop’s palace, a bell tower, and a cemetery. I have visited San Miniato often over the past several months, but have caught sight of the white-robed Olivetans only a handful of times and usually behind the raised counter of the little gift shop where they sell the elixirs, unguents, teas, honeys, and other products they make. Sometimes, as I walk the many steps that lead to the church, I imagine a lone monk peering at me sight unseen through the barred windows of the monastery that sits brown and heavy next to the church’s luminous white and green marble facade. He knows I will enter the church and sit in a pew set on the right side of the nave, the only place in this exquisite, thronged city where I can think clearly—or not at all, it is difficult to say which. The church is often empty in the morning and that’s when I like to walk from my apartment in the Oltrarno east along the river into the San Niccolò neighborhood and up the hill to San Miniato.

In the third century, Monte alle Croci—then Mons Fiorentinus—was home to Minias, an Armenian prince, some claim a merchant rather than a prince, but almost certainly a soldier in the Roman army who had gone to the mount to live as a hermit. Minias was accused of having spread his Christian faith among his fellow soldiers—or was just an intransigent Christian, accounts vary on this point as well. After refusing to obey an edict issued by the brutal Roman Emperor Decius calling for all Christians to make a compulsory sacrifice to the Roman gods, Minias was tortured and finally beheaded near what is now Piazza della Signoria, a few hundred meters from the northern banks of the Arno.

The lives of martyrs tend to be narratively rich and so it is with Minias; legend has it that after he was decapitated, he picked up his head and carried it across the Arno and up to the hermitage where he had lived and where the church named after him now stands. Minias’s bones are said to rest in the altar of the church’s crypt. It is there in the crypt that the Olivetans hold vespers and mass in the early evenings. Dressed in their white robes and so rarely encountered on the grounds, the monks look a little, as they gather for prayer, like an orderly assembly of ghosts. Their Gregorian chants sung over Minias’s bones mellow the room’s dark chill. I don’t understand the chants’ Latin words and still I hear them tell me to leave myself behind.

This spring, chanting could be heard in the nave as well. For his installation Sonovasoro, the sculptor Marco Bagnoli placed five large wooden vases on an ornate zodiac wheel, a particularly breathtaking portion of the nave’s marble intarsia center aisle. The illuminated silhouette of a woman—with her sensuous curves, she distinctly did not look to be the Virgin Mary—was projected onto one of the vases. Sounds—a series of tracks composed and arranged by Giuseppe Scali—emerged from the vases. There were the sounds of chants, maybe recorded in the crypt, maybe not. There were also ambient sounds: dripping water, machines, echoes, respiration. When I took a seat in the nave during the months while Sonovasoro was on display, I situated myself near Bagnoli’s installation in an effort to fill my mind with all those disembodied sounds instead of my own thoughts. I hoped Bagnoli’s dispositions would somehow make me more holy.

Consider Saint Minias carrying his head to its resting place. In bearing such a load—that is, in being narratively and visually represented as having done so—he joins the company of saints known as cephalophores: the head carriers. Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris, is such a figure. After being decapitated, around the same time that Minias was and likewise under Roman persecution, Denis is said to have not only walked with his head in his hands several miles from Montmartre to where the Basilica of Saint Denis now stands, but also preached a sermon during his long last promenade.

The image of Denis holding his talking head is sublime. And sometimes when it can’t touch the sublime, my mind reaches for the tabloid. I think of the strange case of Miracle Mike, a Colorado chicken that was beheaded with unexpected results in 1945. Mike’s executor had missed the bird’s jugular vein and left most of its brain stem intact, and so Mike lived on for two years—and this is true—without his head. For all our cowardice, we humans are not too much like chickens. Which is to say, I’m no physiologist, but it is difficult to think that a human being could by the grace of an auspicious axe swing be decapitated and yet possess the presence of mind—in the absence of brain—necessary to take his head in his own hands, go for a walk, and talk at length. I’m sure I don’t need backup, but Aristotle is with me on this: “…it is impossible,” he writes in De partibus animalium, “that any one should utter a word when the windpipe is severed and no motion any longer derived from the lung.” And yet here I am despite all the impossibilities, eerily enchanted by the thought of a mind having such control over its body that it might exercise that control without the necessary neural pathways, not to mention a few other essentials. I imagine neurons firing and surprised to find that their impulses reach now distant targets, oxygen carried to muscles along invisible corridors.

Minias and Denis and the other saints and literary figures who hold their heads before them must have something very important to tell us. Some of them have staved off death—at least for a little while—to say it. What is it? What does the disembodied head say to the world, to passersby, to itself? In Catholicism, the cephalophoric trope reminds us that not even death can silence faith and the words that broadcast it, words that are quite literally carried to the grave. I know little about Saint Denis, but I imagine him shouting as he left Montmartre, angrily proclaiming his faith, urging onlookers to hold onto theirs. I plug my ears: a lapsed Catholic like me doesn’t want to hear about a faith she has misplaced. Minias, though, is not depicted as having preached during his death walk. He seems to have made his way to his cave in silence, as one might expect a hermit to do. Maybe his eyes searched the path to his hermitage, regarding with intensity the familiar trees and terrain, as well as the guards and companions who escorted him. Maybe the smell of cypress, symbol of mourning, was especially sharp that day. I don’t look to Minias for words, I look to him for an arresting image of indomitable belief and I think of him on that silent walk when I climb the steps to the church named after him.

I want the cephalophores and their ilk to fulfill the promise of their unsettling portraits and tell me something impertinent. I might need to look away from the saints and martyrs.

There is a Hindu goddess, Chinnamasta, who is portrayed grasping her severed head. She holds it up in her left hand, as if it were a prize. In her right hand, she wields a scythe—she has beheaded herself. She stands on top of a man and woman who are having sex—possibly Kama and Rati, the god and goddess of sexual desire and intercourse, respectively. Chinnamasta’s mouth is open, but she doesn’t speak: she is drinking from two of three jets of blood that spout from her neck. The other two jets quench each of the two attendants who flank her.

David Kinsley tells us in his book Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās that there are several versions of the Chinnamasta myth and many more interpretations of her iconography. For some, what is important is that Chinnamasta absorbs, even defeats, the sexual energy of the god and goddess underfoot and turns that energy into sustenance for herself and others. She nourishes. For others, she is too fierce, too dangerous to even worship. Here is a goddess who would cut off her own head. For others yet, she is both things—nurturing and fierce—at once. She is ambiguous.

Kinsley writes that severed heads are liminal, out of place. He associates Chinnamasta and the other more disturbing Mahāvidyās—Hindu goddesses of wisdom—with the rejection of conventions and categories and received ideas—and not merely a defiant rejection, but a rejection that puts the headless and their devotees out there, out of bounds, and thus on their way to enlightenment. Chinnamasta is a figure that I cannot grasp and that’s what I like about her. She is hard to pin down. She is subversive. She has cut off her own head.

One version of the Chinnamasta myth suggests that before Chinnamasta became Chinnamasta, she was Parvati, the divine mother, a far more gentle goddess. She is deep in thought when her attendants complain that they are hungry and remind her that as mother of the universe it is her responsibility to see to it that all her children are fed. She obliges by cutting off her head and hosting the bloody feast featured in her iconography. After she has nourished her attendants, she puts her head back on and the three go home. Chinnamasta is a little pale, but things are mostly back to normal. Having removed her own head for a little while, she pulls herself back together. It is, for Chinnamasta, as easy as that.

The first time I attended vespers at San Miniato, I went with a friend. We took seats in the crypt’s pews, watched as the monks assembled themselves around the altar, and listened as they chanted. Before we knew it, their solemn chants faded and mass, which we hadn’t planned to attend, began. We silently agreed to stay on; it would have been too rude, too blasphemous, to leave. It had been a while since I’d attended mass and my memory for its rituals was fuzzy. I followed the congregation’s cues as to when to sit, when to stand, when to kneel, and when to make the sign of the cross. During communion, while everyone else lined up to receive the Host, my friend and I kneeled. We placed our hands on the pew before us. After a moment, my friend curled his shoulders and bowed his head, letting it rest on his knuckles. He seemed to have relinquished himself. To what, I didn’t know. I remained upright, attuned to his folded form and the movement of bodies through the crypt, all too intact.

Suzanne Menghraj teaches writing in New York University’s Liberal Studies Program and is currently based at the university’s Florence, Italy campus. “With Their Heads in Their Hands” is the last in a six-part nonfiction series Menghraj has written for Guernica with support from a Liberal Studies Faculty Grant. “Seeing in Stereo,” the series’ fifth piece, appeared in Guernica in December 2009.

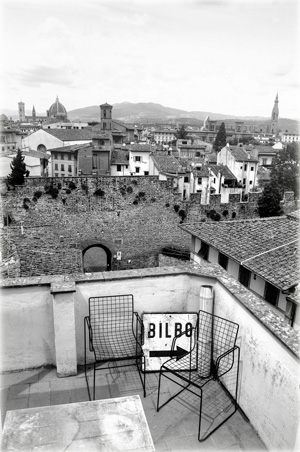

Photo via “Flickr”:http://www.flickr.com/photos/nemos/3713316401/.

To contact Guernica or Suzanne Mengrahj, please write here.