Girlhood, the dazzling new essay collection by Melissa Febos, captures the potency of a woman’s adolescence—an experience that is at once singular and universal, familiar and uncharted, ordinary and remarkable. By plumbing the depths of her own coming of age, interviewing other women about their early sexual encounters, and interrogating depictions of female sexuality in literature and film, the author unravels the stories women learn to tell—and believe—about themselves. In particular, the book probes experiences that Febos believes “marked” her: events she wouldn’t qualify as trauma, but that imprinted on her psyche in ways that became damaging.

She describes being sexualized by men as early as age eleven, then slut-shamed by her peers for the attention. Like many of the women she interviewed for her essay “The Mirror Test,” Febos internalized the stories others told about her (one boy had described her as “loose as a goose”) and, in turn, perpetuated them. In a later essay, she identifies the consent she granted boys during her early sexual encounters as “empty”—a kind of passive deferral that many women will likely recognize. After all, we’re taught to prioritize the needs of men, to protect the male ego and, with it, our own safety. But bargaining with our bodies comes at a cost.

As an adult, Febos can see with clarity what she could not during her formative years. Over centuries, she argues, white male power structures have invented and perpetuated myths about women in order to control their bodies and isolate their minds: the concepts of “witch” and “slut,” as well as the idea that a woman might enjoy being stalked by a voyeur, or hugged by a stranger. The slope is slippery by design, facilitating the minimization and gaslighting that keeps women silent about quotidian humiliations. It’s not like you were groped. It’s not like you were raped. It’s not like you were burned at the stake.

The book begins at the onset of adolescence, when Febos first notices the male gaze intruding on her sense of self. Or, as she puts it, “When I traded the idea of my body as a sublime vehicle for the framework insisted upon by the rest of the world.” It took twenty-five years for her to rediscover the pleasure of embodying her own wildness, an instinct stripped away by the norms and expectations placed on young women by society. By then, Febos discovers that the prize for outwitting the male gaze, or otherwise extricating oneself from its crosshairs, is the ability to sink comfortably into her own skin.

If patriarchy “colonizes our brains like a virus,” as one of her interview subjects named Ada suggests, then Girlhood offers a possible antidote. But it’s not a quick fix. It is the slow and steady sloughing off of an imposed notion of selfhood in favor of one that is freely chosen—and a model for what a post-#MeToo feminist awakening might look like. Earlier this year, I spoke with Febos about the power of speaking the unspoken, the incremental nature of reconditioning, and how women who resist being subjugated by a white patriarchal system threaten its very existence.

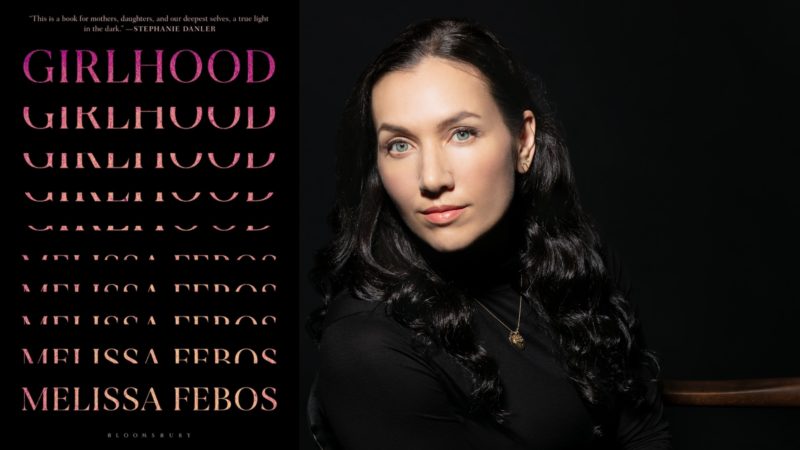

— Sarah Kasbeer for Guernica

Guernica: The topic of female adolescence is a familiar one, yet somehow it seems to have evaded in-depth examination. What led you to dig into this subject matter?

Melissa Febos: I’ve noticed that when a subject becomes familiar, the ways we talk about it start to follow circumscribed routes. As a lifelong feminist and therapy patient, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking and talking about my own girlhood, and I’ve resolved a lot that way. While writing this book, I also realized how much I’d never examined—the creases and crannies of experience and the subtle ways that growing up in a female-identified body under patriarchy had insinuated certain beliefs into my thinking that I’d never questioned. There was, in fact, so much I’d never spoken about, and yes, I think the familiarity of the subject had obscured those silences.

Guernica: In the essay, “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself,” you describe some of your early sexual experiences as a category of “in-between” events: harmful, but not necessarily abusive; things that are damaging but maybe don’t qualify as traumatic. Why do you think we lack words for these experiences—and why is naming them so important?

Febos: As a society, we haven’t been interested in the ways that women are harmed that don’t qualify as “capital-T” trauma for very long. I mean, obviously, lots of people still don’t care, and even more actively want to deny that these types of harm exist. The abuse and subjugation of women’s bodies has been considered the right of men for much longer than it hasn’t. I mean, think of the resistance to affirmative consent legislation—people get really bent out of shape at the idea of men even being expected to ask before they touch you. They would rather women have sex they don’t want than have men suffer the supposed awkwardness of asking for verbal consent.

I couldn’t name the shitty experiences I’d had all through my girlhood because they weren’t violent, they weren’t as bad as the traumas so many other girls and women suffer. I couldn’t name them because there were no other words for these experiences. There still aren’t. The literally unspeakable nature of them led me to never speak of them, to dismiss the clear and lasting effects that they had on my psyche, my sexuality, my relationship to my body, and so many other things. It was really only in writing this essay that I was able to face that.

It is only when we name harms that we can change the dynamics that cause them. Every social movement that I know of began with people sharing their experiences with each other, discovering what they shared and the ways their silence around it had been encouraged and enforced.

Guernica: In the same essay, you write about how women are conditioned to prioritize men’s desires over their own. This influences how they navigate social scripts around sex, which can lead to offering what you call “empty consent.” When I read that, my head nearly exploded. It explained so much from my own adolescence. Did you have a similar a-ha moment?

Febos: Absolutely. After I had a strange, bad experience of consenting to physical touch that I didn’t want as an adult, I basically wrote the essay to figure out why, as a thirty-seven-year-old feminist, I was consenting to touch I didn’t want. I followed that impulse all the way back through a whole lifetime of doing so, of being encouraged to do so. I ended up talking to a bunch of other women who shared similar stories. It was revelatory, and devastating. We had all spent our lives being affected by this dynamic—consenting to touch we didn’t want, and suffering the lifelong psychic consequences of doing so—yet none had ever spoken of it with another woman, or with anyone.

As soon as I named it, “empty consent,” it became so much easier to talk about. If I’d been given that term as a girl, been told about how it might affect me, and that I didn’t have to do it, my whole sexual life might have been very different. Naming is so powerful. It really can’t be overestimated. When things are not named, it becomes so much easier to perpetuate them. That’s the point, I think. It was never “empty consent,” it was always just sex, and so I thought it was just part of sex—doing things I felt ambivalent about and feeling bad about them later.

Guernica: In your twenties, you worked as a dominatrix—paid to tell men “no.” In this book, that experience is just one stop on a journey toward self-reclamation, yet it felt like a critical inflection point. What insights did your experience in sex work offer into your own life, or the lives of other women?

Febos: More than any sex ed curriculum in school, sex work gave me a language for consent and a space to practice having sexual boundaries, even if it was often expected that I’d transgress them in order to make a living. Something I loved about sex work was that it made transparent a lot of the dynamics that were at work with men sexually outside of sex work, but that heterosexual people seemed totally uninterested in acknowledging. It was a space marked largely by pageantry, but also was much more honest than a lot of other spaces where I was interacting with men.

The former sex workers I interviewed all seemed eager to articulate this: It wasn’t sex work that taught us to compromise our bodily integrity for the interests of men, but it did help us to see that transaction more bluntly. We had a lot more agency as sex workers than we often did as adolescent girls or teens interacting with men and boys.

Guernica: You make deliberate mention of the fact that women of color face both sexism and racism, which compounds the harm. Related to that kind of intersectional analysis, how do you think queerness complicates girlhood—and how did it affect your own coming of age?

Febos: I do think that it gave me some space to relate to my own sexuality and to other girls in a way that wouldn’t have been quite as possible had I been straight. The first orgasm I ever had with another person was with a girl when I was sixteen, and I had had many sexual experiences with boys and men previous to that. I write in Girlhood about some of the ways that being queer allowed me to operate off-script sexually as a girl, and the ways that sex with women has been revolutionary for me in the journey of liberating my mind and body from toxic heterosexual conditioning.

I have also found that being pansexual—though I often like to say bisexual, for old times’ sake—and having romance and sex with folks who identify all over the gender spectrum allowed me to observe the contrast between my instincts with folks of different gender identities. That is, when I was with men, I watched myself slip into heteronormative shit that I had no interest in otherwise. Being queer has been absolutely essential to my divestment from so many parts of patriarchy, throughout my entire life. It’s not that straight women can’t do this, but I can see how much harder it is, and I know so from experience. Being able to physically divest from the enactment of social structures is often really key in the ability to divest from them psychically.

Guernica: In several of the essays, you include research about animals. Did entering the ideas through a different lens give you a deeper understanding of them? Did you find that stripping away the cultural context of a phenomenon helped you interrogate it?

Febos: I’ve been obsessed since childhood with the weird way humans dissociate from the fact of our animalness. We refer to “animals” as if we are not animals—it’s truly bizarre, and great evidence of how disturbingly hierarchical our approach to everything is. I used to sit in school looking at the people around me, and marvel at how perverse it was that we all walked around in makeup and plucked out our body hair and talked about bullshit all day. I was acutely aware of the fact that human society as I knew it—capitalism, patriarchy, manners—were all just one way things could have gone, a set of narratives that we collectively decided to collude in every minute of every day. I guess I wanted out. Or, at least a way to talk about it. I have always been really aware of my feral qualities—my partner refers to me lovingly as a raccoon—and bummed that there were so few ways to express them. This book, in many ways, is all about naming what felt unspeakable when I was a kid.

Guernica: Of your adolescence you write, “I had no way to differentiate what aspects of my behavior were inherently me and what were cultural impositions.” Much of this book is about undoing the ideas about yourself that never belonged to you in the first place. How does one see for the first time something that has been deliberately hidden in plain sight?

Febos: Well, you have to want to. I mean, really want to, which is more than feeling uncomfortable with your body hatred or being preoccupied with diet, or obsessed with accommodating men in the million micro-ways that women do, or recognizing your own codependency. Those are starting places, but the work of following those trailheads of discomfort back into yourself and your history and ultimately outward is such slow and painful work, that I think a lot of folks would rather just keep trying to eat less or make everyone else happy all the time.

I actually do it most often in writing, this very slow and careful examination of my own thinking and behavior, and the origins of my patterns. Every morning, I write in my journal: “Today I reject the patriarchy’s bad ideas.” It has to be a conscious choice every day, many times throughout the day. Reconditioning is really incremental, collaborative work. It’s a set of daily practices that organically grow my consciousness, so that I am always seeing more. For instance, I had to consciously practice listening to myself in order to employ an enthusiastic consent policy around touch in my own life. It made for some awkward situations, and totally changed my relationship to my body.

Being in relationships with people similarly interested in that project is really key for me. I have to be talking to other people about it; my primary relationships have to be supporting and engaging me in the process. In my late-thirties, I stopped shaving my armpits, and more than one straight female friend commented that they would love to do the same, but felt like they couldn’t because they were single and wanted to be in a romantic relationship. I don’t mean to suggest that my ways of getting free need to be anyone else’s, but that doing so inevitably requires that we buck social norms that will disrupt our movement through life in ways that lots of people aren’t willing to tolerate. Stopping shaving my pits—like, can you believe that this is still a radical thing to do?—made me keenly aware of how much people, mostly straight people, noticed this, how weird it was to them. It made me more aware of how much of a claim men felt to dictate how my body should be presented.

Guernica: As a society, we talk a lot about the objectification of women’s bodies. But rarely do we talk about how this belief is internalized and self-perpetuated in a way that causes girls further pain. You wrote about mistakenly seeing your own body as “an object that I could yield to others without harming.” What is the relationship between the body and self-love?

Febos: It’s absolutely everything. In many ways, Girlhood is a book about the ways that internalizing my body’s objectification devastated my relationship to myself. Objectifying something estranges us from its humanity. Being estranged from my own humanity set me up for so many fucked up things—including, ultimately, my own workaholism, my capitalistic resistance to rest, not to mention, of course, overriding my own desires and comfort to accommodate my body’s uses to other people. Self-love doesn’t exist without the body. We are our bodies. It’s so simple and yet so incredibly hard to internalize.

Guernica: Your story of the teenage girl, Jenny, who repeatedly telephoned your family’s house when you were in junior high, called you a “whore,” then hung up reminded me of one of the premises of Kate Manne’s book Down Girl. She suggests that misogyny is the enforcement arm of sexism, used to punish women who step out of line. Why do you think women willfully participate in this system as enforcers?

Febos: Women are conditioned to discipline their own bodies and each other’s bodies because this is an incredibly efficient way to maintain the status quo. Participating in the power structures of patriarchy is just another form of perpetuating them.

Some of the most toxically patriarchal people I’ve intimately known have been women. We can sometimes personally benefit from the hierarchical and misogynistic power structures at work—it’s by convincing us of this that we get convinced to reinforce them, but ultimately it’s at the cost of our own communities, our own minds. This is a dynamic that occurs within every kind of oppressive power structure, of course.

I don’t think Jenny was an example of that dynamic, ultimately. Later in that essay, I describe encountering her at the motel where we both worked as maids a few years after she harassed me, and how we became pals. As is the case in every such situation, we were both victims, both being consumed by a value system that ultimately wanted us preoccupied by the illusion that a man’s attention was precious and worth fighting over, rather than realizing our power and growing it by supporting one another, or investing that energy in our own further empowerment.

Guernica: In your essay “The Mirror Test,” you write that the concept of “slut” was invented by men and weaponized to “keep women isolated from their own pleasure, their true selves, and one another, and to prevent them from challenging any aspect of male domination.” How does a girl defining her own sexuality threaten male power structures? Why is society so hell-bent on controlling women’s bodies?

Febos: I mean, there are oodles of feminist scholars who have explained this better than I can. Let me put it like this. When I was an adolescent girl, around the time that I underwent the experience of slut-shaming that I write about in Girlhood, my thinking generally ran on scripts that had been socially programmed. I spent an enormous amount of energy trying to discipline my body to make it attractive by a standard that I had not chosen. I spent enormous amounts of energy assessing my body’s value and appeal to boys and men, and submitted my body to them as if they were owed it, despite those exchanges rarely being pleasurable for me. And I was a weird, queer, super smart, artistic, feminist kid, with a queer feminist mom! Even so, society’s successful methods of controlling my body and sexuality all but subjugated my entire being as a girl.

Now that I have undone much of that conditioning and rejected patriarchy’s attempts to control my sexuality, I am partnered with a woman and have only enthusiastically consensual sex that is highly reciprocal and multiorgasmic. I give not a single fuck what any man thinks of me or my body. I am mostly not available to serve their desires, their industry (that one is the trickiest at this point), or their emotional needs. I am almost entirely in community with women, queers, and gender-nonconforming folks. I bring feminist, antiracist practices into every space that I inhabit, including the classrooms where I teach young writers, and I spend the rest of my time writing overtly feminist books. I am a living explanation of why society is hell-bent on controlling women’s bodies: When our bodies are not controlled, women tend to become hell-bent on changing our society.