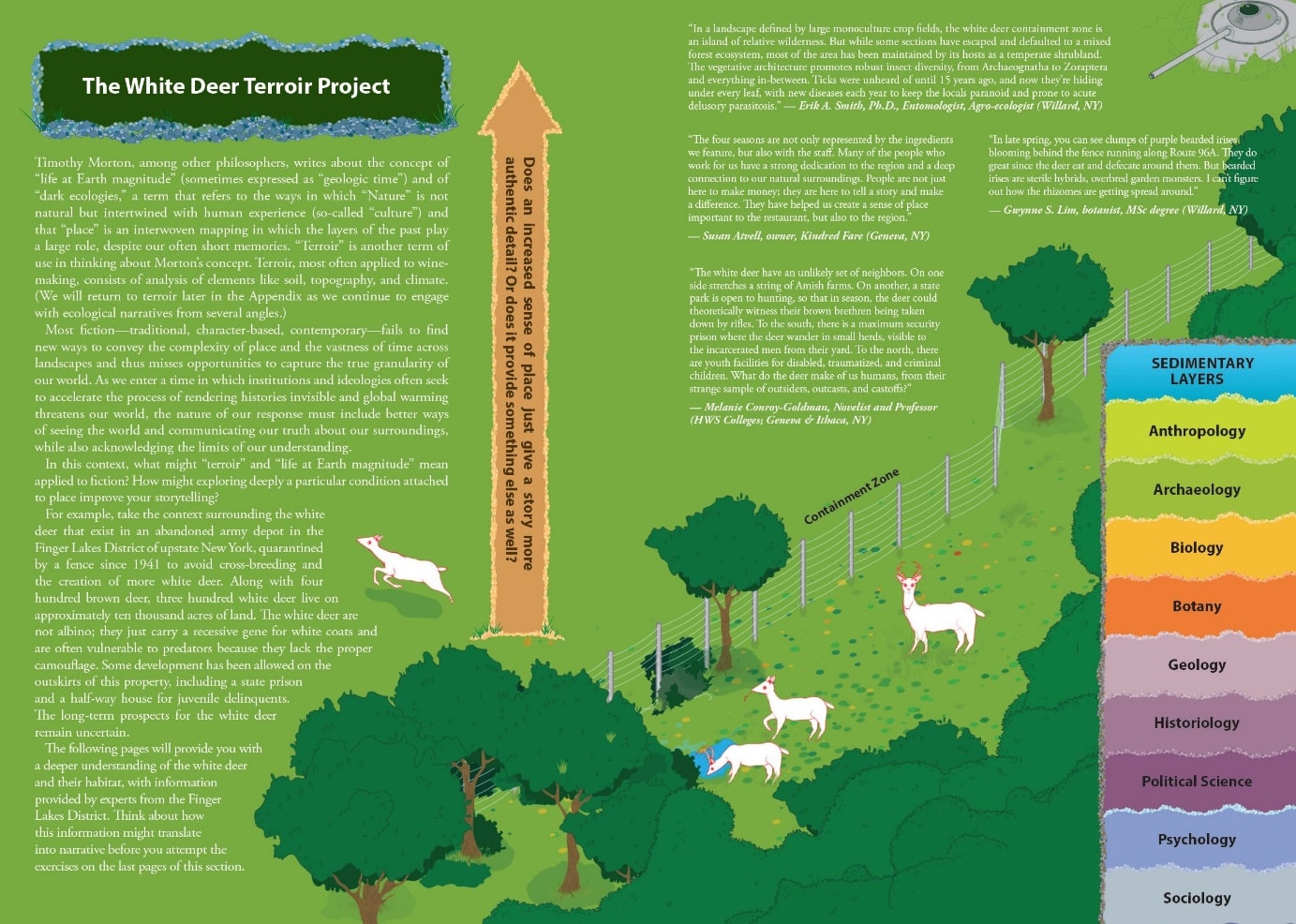

The recent release of my expanded Wonderbook, a fully illustrated writing guide, includes a new eco-storytelling module entitled “The White Deer Terroir Project.” It’s based on a semester of teaching I did at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (HWS) in upstate New York. While there, I encountered the abandoned US Army depot near Lake Seneca that now serves as the fenced-in home for about 200 white deer. These white deer are not albino; their white color is caused by a recessive gene that leads to their fur lacking pigmentation. Given these animals’ rarity, the abandoned depot has become a flash point for environmental discussion, especially in light of a recent proposal by waste-to-energy company Circular enerG. The company proposes to develop a trash incinerator on the site, which would burn approximately 2,640 tons of garbage each day. The proposal is under review with the town of Romulus’s Planning Board, but meanwhile, scientists and conservationists argue that the waste plant will emit lead, dioxins, mercury, and other toxins that are dangerous to the deer and other wildlife.

The intricate relations between the depot, its deer, and its fragile ecosystem made me think about how looking at a particular place’s terroir—a term used by wine enthusiasts to refer to the environmental factors that influence the growth and development of wine grapes—might help students to better understand a place’s complexity. And this, in turn, could help them generate stories, as well as explore how stories get told.

The Wonderbook module sets out the general parameters of what such a project might look like for a creative writer. But after discussing the project with biologist and HWS professor Dr. Meghan Brown, I wondered if perhaps she could teach the module in one of her science classes. What might be the benefits and unexpected results of teaching a creative writing lesson in the context of a science class? How might examining the results of this experiment help fiction writers think about their own approach to the project? I felt it was important to answer these questions in an era of climate change, when activism and new ways of looking at the world are needed across disciplines.

Brown, an associate professor and chair of the biology department at HWS, studies the ecology of lakes and is particularly interested in how organisms survive changes to their environment. She has also worked with communities and students around the world, including the lake district of Italy during her Fulbright research fellowship. I knew she’d be an excellent candidate to take on this experiment, and to my delight, she did. During a recent semester, she assigned her students variations on the “White Deer Terroir Project,” with a related postcard exercise. (A description of her main project and the related postcard exercise can be viewed online now, along with a lesson plan and student samples.)

I interviewed Brown shortly after the semester ended to talk about the experience, including what her students learned; what surprised them the most about the project; and what challenges she and her students face, then and now, when trying to communicate scientific discoveries to the public.

VanderMeer: How did these two exercises fit into your class as a whole?

Dr. Brown: I developed these exercises for my Invasion Ecology course, which is pitched toward undergraduate science majors. The writing project was essentially a multiple-week lab exercise during the middle of the semester. Instead of having a field lab or a bench-top lab where we tested hypotheses through experiments or observations, the writing project was a “lab” where students explored hypotheses through their fictionalized versions of the Seneca Army Depot. This worked really well, because it is challenging to have the students actively doing science with the restrictions of four-hour weekly labs and upstate New York winters. The fiction project allowed us to work creatively and “do” science through writing, instead of more passively reading and discussing the literature.

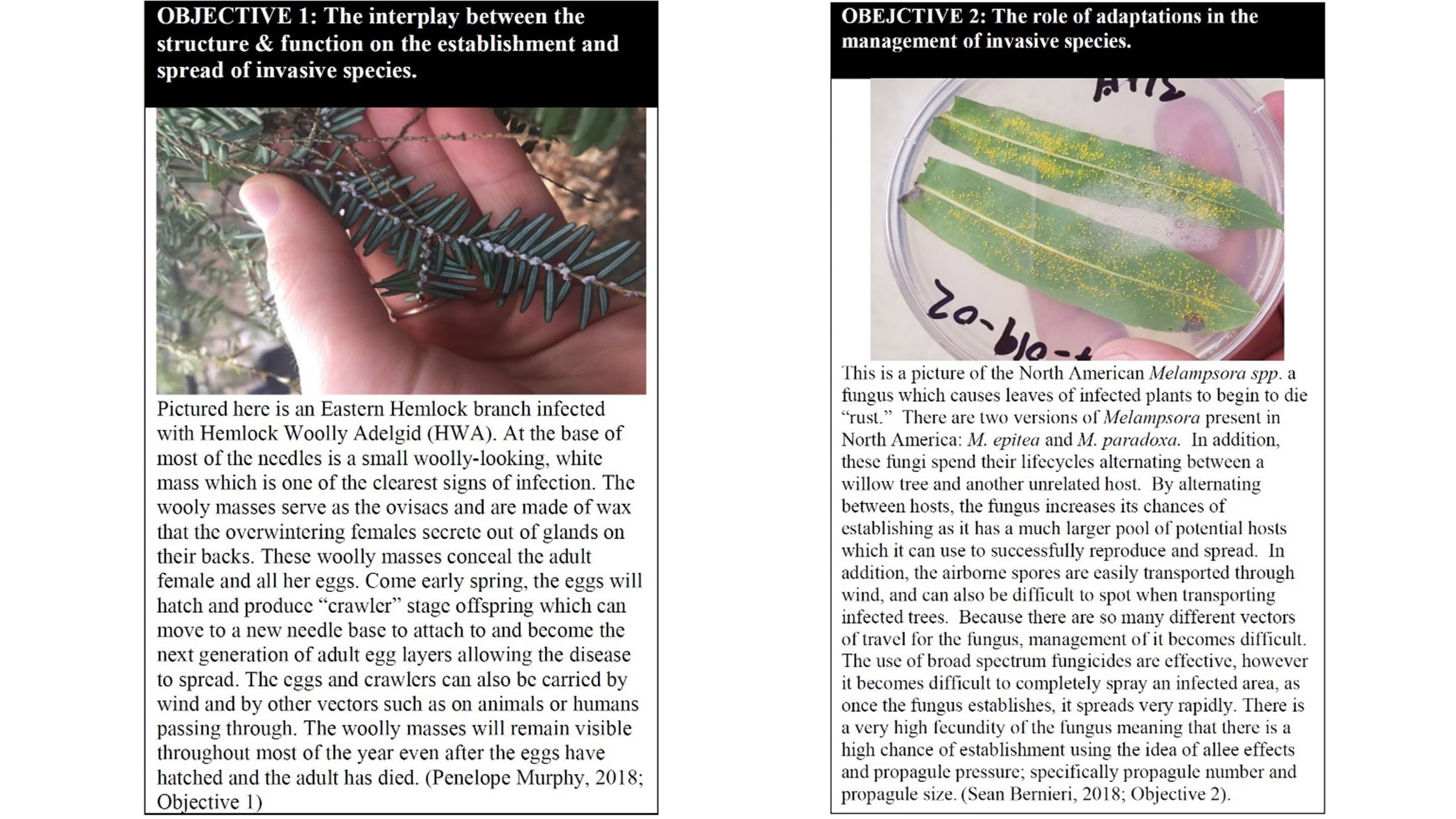

The postcard assignment is an exercise that students repeat several times over the course of the semester, to communicate their learning after visits to field sites. The depot was one site, and we also visited some Nature Conservancy land that was struggling with an invasive insect, theHemlock Woolly Adelgid. At Cornell’s New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, we learned about their research on invasive species and using biological control to address agricultural pests.

From a teacher’s point of view, it is more pleasurable to grade work like this. I also see more impressive responses from students while doing these kinds of projects than what follows from canned questions or appears in long-format papers.

VanderMeer: How aware of the ecology of the Finger Lakes District were your students, in general, before taking this class with you?

Dr. Brown: This course is populated by mostly biology majors with a couple of years of science classes under their belt. That being said, we have a fairly open curriculum in the biology department (we don’t require ecology, and most students have had no formal class in ecological theory and methodology). I could drone on about the downsides of that, but the plus side is that students often have a diverse knowledge that, if played well in class discussions, brings a lot to our conversations.

For example, one student might have taken a population biology class, and therefore understands the variation and adaptions that influence the spread and resistance of disease in deer. Another student might have had a microbiology class, and therefore understands the mechanisms of a particular disease in deer. These students (and the rest of the class) teach and learn from each other. Further, once students are thinking like ecologists, it doesn’t really matter if their knowledge is about the Finger Lakes or the deep sea or the desert; these systems are all playing by the same rules. All that said, some biology students graduate with very limited specific knowledge about the Finger Lakes. And that is too bad, but I suppose that leaves room for them to learn about other interesting aspects of science.

VanderMeer: Did your students know about the white deer before taking your class?

Dr. Brown: Maybe a few of them—those who grew up around here. But many were not aware of the deer population, and those that were didn’t know much about the animals. For example, they might have thought the deer were albino.

VanderMeer: What seemed to surprise them most about the white deer and their environment?

Dr. Brown: I know from their writing that many students were fascinated with the army depot and its clandestine nature. One student framed her story around the Women’s Encampment, a feminist peace protest of the ’80s. Many students took to the disjoint between this rare population of white deer and the depot as military land with WWII history and capacity for nuclear storage. Our tour guide told the students that practice drills for the raids to capture Osama bin Laden were conducted at the depot. His capture would have been at the time when the students were very young and just starting to process world news, so I think that fact influenced some of the fantasy in their stories.

VanderMeer: What did you have to adjust or add beyond the material laid out in Wonderbook?

Dr. Brown: Certainly, the hours we spent at the depot, seeing the habitat and the deer, were important. Our tour was conducted by the president of Seneca White Deer, Dennis Money, who had a deep knowledge of the land and a formal education in natural resources. Back on campus, we had discussions and workshopped writing that pushed students to make the connections between science and fiction. I read student drafts at several points along the way, and students were reading each other’s writing, which promoted a dialogue and eventually lessened the guardedness of, “I’m not a good writer.” By the way, students also say, “I am not a good scientist,” or “I am terrible at stats,” or “I am more into human biology.”

I also had the students’ input on developing the grading rubric. I had my own ideas about which critical aspects would make the project successful, and students contributed theirs. I then shaped the grading criteria and vetted them one more time with the students. That extra classroom time was important if students were going to buy into a fiction exercise for a science class, and I will definitely repeat the process when I teach the project again.

VanderMeer: How does having a connection to a place inform the study of that place scientifically?

Dr. Brown: My own experience is that I am curious about and engaged in places where I live, where I travel, where I seek solace and adventure. All my published work has taken place in systems that I’m appreciative of and fascinated by in non-scientific ways. Some of those personal connections are long-term commitments, such as my work on invasive species in the Finger Lakes region, where I am raising my children. But other connections are more ephemeral and academic, such as a stay in the lake district of Italy, where I transitioned from student to professor. As an aquatic biologist, I spend a lot of time thinking about how lakes—which are also sources for drinking water and sewage disposal—serve as moderators of our climate and as sites of meditative and recreational respite. They also respond to anthropogenic pressures, and in turn, record centuries of changes. Those connections require ways of knowing that aren’t just scientific.

VanderMeer: How has your view of the area changed over time, from when you first came to the Finger Lakes to now?

Dr. Brown: When I first moved here, I found the landscape of the Finger Lakes pretty, but I could only drive by it, because it was difficult to access on foot. I missed the large lakes, expansive wild beaches, and forests of the upper Midwest, where I was raised and eventually returned for my Ph.D. research. This didn’t deter me from frequenting spaces in the Finger Lakes for quiet walks and exploration. Over the years, I’ve come to take a lot of pleasure in the rewilding of places near our house—the railroad tracks, the brambly forest, and a nearby graveyard—as well as more formally reclaimed lands such as the army depot and Sampson airbase. I also love the spectacular waterfalls and ravines that border the lakes. Now I have a great appreciation for the agriculture and architecture that make up a large part of the Finger Lakes’ character. My favorite view is from the middle of one of the lakes. From there, my home looks dollhouse-sized. The pastoral landscape has a great appeal and comfort—one that, at least for me, is distinct from more dramatic places. It has a gentler pallor that lets you linger.

VanderMeer: As a scientist, what do you see as the biggest challenges in conveying information to the general public?

Dr. Brown: I suppose it is like most things: people generally listen to what they want to hear, and from that limited information adopt whatever fits into their world view. I think that makes us allergic to nuance, which is what science is all about. As a scientist, I thrive on the uncertainty, the variability, the unknown; but the public often wants static, deterministic, linear responses to complex questions. It is a balancing act, to keep faithful to the science (and my love of its complexity) while building a story that communicates the gist of the problem or solution in a way that general audiences can understand.

Dr. Meghan Brown is an associate professor and chair of the biology department at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (Geneva, NY). She studies the ecology of lakes and is particularly interested in how organisms survive changes to their environment. She has authored numerous scientific publications; been awarded prestigious grants from the National Science Foundation, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and Great Lakes Protection Fund; and assisted the National Park Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, and Native American reservations with their research into and protection of aquatic ecosystems. She has also worked with communities and students around the world, including the lakes district of Italy during her Fulbright research fellowship; Lake Baikal, with support from the US Department of Education; and Lake Atitlan (Guatemala), where she recently taught a course focused on the intersections of culture and ecology.