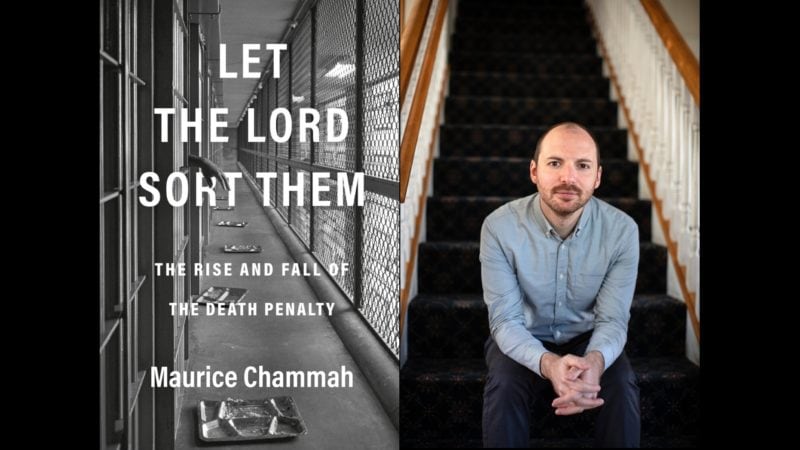

In 2016, it looked to lawyers and activists like the nation’s general ambivalence toward the death penalty had brought an end to its practice. No federal death row prisoners had been executed for nearly seventeen years. Then Donald Trump was elected president. Since July 2020, thirteen people have been executed by the Trump administration, an extraordinary number and concentration of federal killings. In his new book, Let the Lord Sort Them (out January 26), Maurice Chammah recounts the rise and fall of the death penalty in the US from the vantage of Texas, his home state and “the epicenter of the death penalty over the past fifty years,” Chammah told me, where “history is rife with heavy symbolism about violence and honor and justice.” He is a staff writer at The Marshall Project and a former Fulbright scholar who lives with his wife in Austin. I’ve known Chammah since 2012, when his work was published at The Revealer, where I was editor-in-chief.

We spoke by phone in the first week of January, as white nationalists were storming the Capitol, waving Confederate and “Stop the Steal” flags in the rotunda, beating cops in its hallways, and erecting a gallows on the nearby plaza. At the same time, in Terre Haute, Indiana, defense lawyers were working feverishly to save the life of fifty-two-year-old Lisa Montgomery, who had been sentenced to death for brutally killing a pregnant woman, Bobbie Jo Stinnett, and cutting the fetus from her body. What Montgomery’s lawyers failed to reveal during their client’s 2007 trial were the horrifying experiences that had defined much of her life. As a child, Montgomery was prostituted by her mother to pay the bills and repeatedly raped by her stepfather and his friends—for hours, often three at a time, in a room built onto the side of the family’s trailer for that purpose. As an adult, Montgomery had multiple abusive relationships. She suffered brain damage and dysfunction, something that experts in abuse and trauma say should disqualify prisoners from receiving the death penalty. The Supreme Court disagreed. On January 12, Montgomery became the first woman to be executed by the US government in almost seventy years.

—Ann Neumann for Guernica

Guernica: Justice, and the reasoning for using death as a punishment, are defined and redefined throughout the movements and eras you cover in this book. Is the death penalty a deterrent, is it reform, is it a cultural practice—shaped by what you call the “mythology of local control”? Do we kill criminals because they are irredeemable? Do we want closure or rights for victims? All of these different ways to justify state killing kept coming up throughout the book. And so I guess the semi-naive question I have is, why do we still kill?

Maurice Chammah: The more I went era by era and understood these different justifications, and the more conversations I had with the people who really stood by death sentences and executions—whether it was prosecutors, the executioners themselves, or the family members of victims—over and over it seems people have a kind of gut instinct for revenge. That instinct for revenge also comes out in the abstract: a member of the public who answers a Gallup poll and says, Yes I believe in the death penalty for murder, without any details about a particular crime, that sounds right to me. There are some arguments out there that it’s biological or evolutionary and I don’t go deeply into those—they’re in a footnote—but the more conversations I had the more I understood that that gut instinct is real. What varies are the intellectual justifications for the death penalty.

If you are the family member of someone who is murdered, you really don’t have to do much work to justify your vision that somebody should die. But once you get up to the higher level, the prosecutors making the argument to a jury and to judges on appeal about why this person needs to be executed, you start abstracting those gut instincts. You start saying, “It’s not just that I feel a revulsion and that this person doesn’t deserve to live any more, it’s that they are irredeemable, or a monster, or going to be dangerous in the future—which makes it almost abstract and scientific sounding.

Guernica: Your history of the death penalty is told through the stories of countless dedicated, outlandish, alarming, colorful characters, from the prisoners and their families to attorneys and district attorneys their lives depend on. Are they part of what makes the story of the death penalty so intriguing?

Chammah: Absolutely. I knew there were these larger than life characters who would be fun to write about and any reader would find very compelling: the swashbuckling district attorneys who really made a name for themselves, and even governor George W. Bush. “Characters” is a funny and not ideal term, because these are real people. Although there was a pleasure writing about them there was also something very daunting about going very deep with people—and trying to be conscientious about how I would be making them more public than they’d ever been by putting their stories on the page.

Guernica: There’s a lot about class and race in everything they’re doing but I still don’t know how much of the country would say, Yes the death penalty is a racist practice.

Chammah: One thing that appealed to me about Danalynn Recer [trial attorney and director of the Gulf Region Advocacy Center] was that she was one of the few white defense lawyers who looks race squarely in the face. She got to race through her scholarly interest in lynching, and tells the story of being the only white student in some of her African American history classes and having this realization that the study of the history of lynching is also the study of, as she put it, “What the hell is wrong with white people?” There’s something really valuable in showing Danalynn to readers, many of whom are going to be white readers, as one model of what an ally looks like in a discussion of racial justice. I want people to see what it looks like to dig in and make it our life’s work to address these problems.

Guernica: One person whose story runs through the book who was very compelling—and made me very uncomfortable—was the chaplain, Carroll Pickett. He has seen more than 100 executions, which I can’t fathom.

Chammah: I don’t think he can either, to be honest. Carroll Pickett is the first character that readers encounter with any interiority at all. And I was really lucky to even get to do an interview with him because his health took a real turn really soon after we spoke. Pickett was a chaplain for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice; he witnessed dozens and dozens of executions, and even more fraught than that, he was the man many would spend the day talking to before they were executed. He got an intimate portrait of these men and he was haunted by many of them. He himself wrote a very good memoir about his experience called Within These Walls.

But I thought Carroll Picket captured our larger ambivalence about the death penalty. We maybe feel queasy about individual cases, we struggle as a country to synch our support of the death penalty with our larger Christian culture. He himself is a very religious man. We struggle often to comport our personal view with the things we’re asked to do as part of our jobs and livelihoods, the moral compromises that life in America in the 20th century entails. The death penalty is part and parcel of these large themes about culpability and violence. They go beyond the death penalty, but squarely come into the death penalty through the role of a chaplain—the man who’s supposed to be comforting the condemned man before his death, getting to know him, help him, but also in a sense smoothes the way to his death.

In the opening scene of the book, Pickett learns there’s going to be an execution, and doesn’t know his role is going to be, and this is his quote, to “seduce the emotions of the prisoner.” He thinks he’s helping the prisoner; then he learns that he’s actually helping the institution, the political machinery—so there’s no scandal of a man fighting his death. The sense of compromise and culpability was so complex to me, and so evocative. It speaks in a broad way about how we struggle with our own culpability in these systems every day and across a broad range of institutions in our society.

Guernica: The book captures how far-reaching the ripples of this pain are, created not just by the original crime but by the criminal justice system itself.

Chammah: When I first started doing oral history interviews around the death penalty ten years ago I was surprised and stunned at how far the ripples go. Someone is murdered and then the family members of the person who committed the murder live with the death sentence hanging over their head. Then there’s the family of the person who’s been murdered and the lawyers who go home at night having spent their day working on legal arguments and presenting in court about these horrific events.

The act of execution produces more violence in a literal way, but it also brings the violence of the original murder into the public eye over and over again. To personalize it, yesterday I was working on a short piece about the case of Lisa Montgomery [the woman executed by the administration on January 13, 2021]—and the crime is horrific. I mean the horrors are so intense, and on the one hand it’s important that we as a society look violence squarely in the face and try to understand the larger causes of it. On the other hand executions, through their drama, continually subject us to the sort of tawdry, horrifying, stomach-churning details over and over again, and ultimately some damage is done from that: to have these stories of violence circulate over and over for so many people. You don’t even know how this trauma infects your brain.

Guernica: I was fascinated by the role that religion played in this history, from Carroll Pickett, the chaplain who has a complex relationship to his job, to the title of the book, Let the Lord Sort Them. How did you get to this title?

Chammah: The phrase is actually not from the Bible in any real way. It was said during the crusades and then became a kind of meme in American culture, especially around the Vietnam War, there were patches on jackets that said it. Once I had that phrase rattling around in my head it popped up frequently in the reporting. There’s a quote about Johnny Holmes, the district attorney of Houston, that says he’s a real “let God sort them out” kind of guy. It appeared on the T-shirt of the first woman to be executed in Texas in recent times, Karla Faye Tucker, as the embodiment of her devil-may-care attitude toward murder.

The Bible does not speak with one clear voice on the death penalty; you can find a basis for supporting it or opposing it in the text if you want to—and many people throughout the course of the book do that. But it was also central to everyone’s answers about their personal beliefs, it came up constantly and I thought religion needed to play a role in the title and in the framing of the book because religion is such a big piece of the mythologizing quality of this particular punishment.

Guernica: Tell us a little about Tucker: her charisma, her faith, and the significance of her case?

Chammah: Twenty-two years ago Karla Faye Tucker committed a really gruesome murder in Houston; she left a pick ax in one of her victims. It was one of those crimes that we usually describe as senseless. She went to death row for murder and had this very dramatic conversion to Christianity. By 1998, she had become sort of famous in evangelical circles. She was on major evangelical television shows; Larry King had interviewed her. Texas Governor George W. Bush, who had a very dramatic conversion to born again Christianity himself, did not allow her to be spared. She was executed in 1998.

Karla Faye Tucker was definitely charismatic and I think gender played a complicated role in her case. We traditionally see women as the ones to protect and the weaker part of society. Watch those older videos of her being interviewed; she really is radiant. There’s nothing even remotely false about her devotion to her newfound faith. That said, an argument that was made at the time and that I think is worth bringing up over and over, is that, had a black man made the precise same argument, had he been exactly like her in every way except for being a Black man, I’m not sure it would have resonated as widely for people.

Tucker’s case, in retrospect, augured the later decline of the death penalty insofar as she was a first dramatic case in which people debated not the question of Is the person we’re killing innocent? but: Can a person change so much that the person we’re killing isn’t really the same person who committed the crime? What is the role of redemption in our larger system—especially given that many of us as Americans believe in a Christian understanding of God and mercy and redemption?

Conversion narratives are such a huge part of American culture. The Tucker case really tested us: Do we believe that everyone is capable of redemption? That case came and went, but after 1998, you start to see more moral arguments against the death penalty, arguments in court that people can be redeemed. And you see more appeals by defense lawyers to the Christian underpinnings of our society.

Our society over the last twenty to thirty years has tried to resolve the ambivalence about the death penalty with those ideas. The Karla Faye Tucker case was the bellwether and we’re still seeing it play out. Even the harshest, most fucked up prisons in the South, like in Louisiana and Mississippi, have rehabilitation programs that are very bound up with Christianity. Donald Trump was pardoning people; in his State of the Union address he said that we’re a country that believes in redemption—even as he speeds through these executions.

Guernica: You write extensively about the lawyers who kind of pioneered the defense of prisoners on death row, working endlessly to save their lives. At one point you note the mindset, quite different from the general public at the time, that many of these people shared. “In order to defend someone properly, you had to study the ‘diverse frailties’ that had produced the act of violence the state was now seeking to punish. And once you did that you no longer saw these men as monsters; you saw the state as a monster.”

Chammah: I was very riveted by this world of defense lawyers in the early ’90s because so much of what they say feels like it’s part of the liberal consensus now, but they were outsiders when they were making these arguments then. They were [seen as] kooky lovers of criminals, like Why would you waste your time trying to defend this man on death row? I mean this was an era in which Joe Biden, it should be remembered, was promoting the death penalty on the floor of Congress and Democrats were lining up along side Republicans to voice their support for very punitive crime policies.

In that context these defense lawyers were very motivated. They came to this little house in Austin [the Texas Resource Center] and fed off each other and there was a kind of bunker mentality that set in. Only now are these people starting to see their work accepted as noble in a mainstream way, but for years, even decades, they were being continually traumatized by seeing their clients executed while also earning the scorn not just of politicians but of their family members and friends. They would hear, How can you defend those people?

And all of them had to reckon with that for themselves. I wanted to go deep on their little culture because it felt like it spoke to our current moment so clearly. and there was something very inspiring about these people. There are plenty of ways to be a public interest lawyer that don’t involve earning scorn, so there’s something a little eccentric about choosing to do it.

I also wanted to investigate what it is that turns people into these zealous, almost prophet-like devotees to the hardest causes and what personality strengths and flaws you need to become that kind of person. What are the costs of being that kind of a person, and how do those people end up shaping history?

Guernica: The book is just full of these people who are teaching us about their own moral lines. The defense lawyers were doing this work because they thought it was the right thing to do.

Chammah: Absolutely. And I think I probably spent so much time on prosecutors and defense lawyers because I’m a writer who feels compelled to tell stories about really extreme and tragic things. A generation ago they gave their lives to basically the same thing. I also want people to get a sense from this book of the roads you can travel in life and how immersing yourself in certain institutions can produce a personality, produce a life. In the case of these lawyers you could really see it quite dramatically.

I was trying to get readers to see how much power they have as voters when it comes to the criminal justice system. For better or worse, our system really does respond to democratic organizing and movements. It’s slow and it’s imperfect, and fear often beats mercy, but a huge part of why the death penalty disappeared is because we voted for district attorneys who don’t seek it any more. We’ve conveyed in election campaigns to governors and presidents that we want a new vision for the criminal justice system. I wanted the theme of culpability to come across so that by the end you’d feel like, I am myself a part of this bigger system and I play a role.

There’s such a tendency to offload responsibility when it comes to public policy. You constantly see people do it in the book, and say Well it’s not really me, it’s actually the other person; it’s not the prosecutor, it’s the jury; it’s not the executioner, it’s the governor; it’s not the governor, it’s the parole board. Everybody is offloading their responsibility at every turn while trying to put tons of responsibilities on the prisoner and in some cases the defense lawyer.

By the end I want you to feel like, God, maybe I also offload responsibility sometimes. Maybe I should think about why I do that—and how I can not do it—as a member of this society. Voting is such a simple version of that. I want people to feel a sense of responsibility and culpability for this system we have—and for the work to produce a new one.