Mark Bibbins and I have known each other for the better part of twenty years. We have very close friends in common. We have shown up at the same Thanksgiving dinners and readings, or in Provincetown at the same time. Last year we even flew from Portland to JFK on a redeye, post-AWP, seated side by side, which means Mark has probably heard me snore or make funny sounds in my sleep as my head rolled forward. I’ve always loved his work.

We decided to talk after realizing our new books—his brilliant 13th Balloon, an elegy-in-verse for his boyfriend Mark Crast, and my memoir Later: My Life at the Edge of the World—both look back at the early 1990s, a moment when the AIDS crisis was especially fraught, when none of the drugs worked, and so many of our friends were dying. What was it like to survive under those conditions? And what did we carry with us from those times to the present? Did we ever leave, at least psychologically? What follows is a record of a month-long conversation. A record, too, of getting to be better, deeper friends after knowing each other casually for so long.

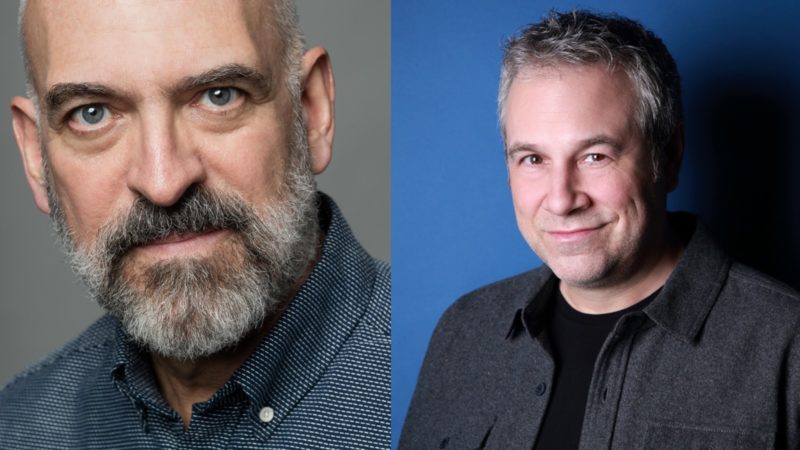

—Paul Lisicky for Guernica

Paul Lisicky: I’ve been thinking about the fact that both of our books are coming out in 2020, close to thirty years after some of the bleakest years of the AIDS crisis, before antiretrovirals. I have my own thoughts as to why it took me so long to give shape to this experience, and I’m curious about yours. 13th Balloon does an incredible job of capturing that unnerving paradox of temporal distance and emotional proximity. Two passages that haunt me: “When I cut into the past / what leaks out is you” And: “Strange to look vainly for oneself in history / and stranger to realize / that there is a chance / one might find oneself there” Did it ever occur to you to write about the loss of Mark, and the dread and complexity of those years, at an earlier point? Why did you wait until now?

Mark Bibbins: You’re right that a lot of time passed, though I didn’t (and don’t) feel like I was waiting, which implies that I consciously chose not to write about those experiences, that I held off for some reason. So many writers—poets, novelists, essayists, playwrights, queer and otherwise—were documenting the AIDS crisis (which is a phrase I’m almost tempted to put in quotes) in real time, in beautiful and harrowing and necessary ways that I found inspiring. If that could be called a community I felt like part of it, albeit peripherally, as I was just starting out as a poet.

I did write and publish a few poems in the mid-90s about Mark’s death, and then my work swerved away from overt autobiography and stayed there for quite a while. Looking back, I note that this swerve coincided with the development of treatments for HIV and AIDS that actually worked, at least for those who had access to them. Now it seems that temporal distance and, perhaps paradoxically, emotional distance were necessary in order for 13th Balloon to achieve the emotional proximity you mention, but again, it was not a conscious choice for me. When the first pieces of it started bubbling up five or six years ago they took me by surprise.

So much of my book still feels ephemeral to me, almost unreal, while Later is vivid, grounded, specific—at one point you describe an outfit you were wearing: “Today I have on an olive T-shirt, skinny white jeans, a blue bandana on my head.” I’m afraid this is a terribly naive question, but were you keeping a journal or diary at the time? You had gone to the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, where most of Later is set, specifically to write—did you have a memoir in mind even then? Either way, I would ask of you the same question about publishing it: Why now?

Lisicky: It’s interesting to hear you say Later feels vivid. I think of the early 1990s as being an extended dream, but at the same time I remember very specific perceptions, incidents, conversations. I couldn’t have anticipated what it would be like to move into a community that at that time was a haven for people who were sick, dying, or about to die. Instantly, everyday life became very intense: sadder, funnier, scarier, sexier, more absurd. Everything seemed to matter more than it would otherwise because a community, a way of seeing, was up against being struck out, excised, every day. I’ve never felt day-to-day survival that acutely, before those days or since. I never really needed to write any of it down in a journal because that experience has been right at the front of my imagination for close to thirty years. Ask me what happened in Provincetown from 1996 onward, once people stopped dying in alarming numbers, and my memory of that place is far less precise.

As to why to write it now? Well, my father developed pneumonia about five years ago, right after the New Year. He couldn’t shake it, went into the hospital, then into hospice. He had last rites. Then, days later, he walked out of hospice and moved back into his apartment. This happened in three cycles over the course of six months. You probably can guess where this is headed. My father was 91, didn’t have HIV, but the trajectory of his multiple illnesses felt awfully familiar. A few weeks after he died I started writing the first draft of the book. The decision wasn’t conscious. I was back in those times again.

At around the same time my doctor had brought up the prospect of my going on PrEP. To make a long story short, I’ll just say that taking it once a day has changed my relationship to time—it occurred to me that I’ve lived most of my life not really believing in the possibility of a future, even though I never seroconverted. That particular treatment feels like a milestone, another shift in a long ongoing narrative that doesn’t seem to have an end. How could anyone believe it’s over when there are still 37 million people in the world with HIV? And yet that marker is another intuitive reason to tell the story of those earlier days before it’s lost to time for good. And taking that pill is a daily reminder, makes it all more visceral, less abstract.

So back to our books—I was thinking about the fact that I wrote my book with short titled sections, as if it were a book of poetry, and you wrote your individual sections without titles. In my case, I didn’t want Later to feel too connected or resolved. Maybe I felt the book arching toward that and I tried to do whatever I could to disrupt the form. But in 13th Balloon the implied continuousness does so much to make for an ongoing, absorbing, dynamic experience. The reader can read the individual sections out of order, as they might with any other collection of poetry, but they could also read it consecutively, from front to back. I wondered if you could talk about the form of the book.

Bibbins: I love what your short, often oblique section titles (like “Foglifter,” “Twinship,” “Refusal”) do for the pacing of Later; they seem to snip off and encase moments in time without isolating them completely, so there’s still this wonderful continuity and flow. Working without titles in 13th Balloon may have caused me to put more pressure on the endings of the individual pieces—in retrospect that’s how it appears to me anyway. It’s my first crack at a book-length poem, and I didn’t group the fragments by subject matter or arrange them in chronological order, so, as you note, it can be read front-to-back or out of sequence. Each piece ends with three forward slashes, which I added to the manuscript early on without giving them much thought—they could easily have been asterisks or anything else—but I realized they could indicate a “poem break” in the way a single slash represents a line break when verse lines are quoted in prose, and two slashes represent a stanza break. W.S. Merwin said “the mind does not think in punctuation,” and apart from the occasional hyphen that I couldn’t in good conscience leave out, the book is unpunctuated. I felt it needed some visual element to keep everything from blurring together, so hopefully the slashes accomplish that.

You’re absolutely right to point out that while our books deal mostly with events that happened decades ago, the crisis is ongoing. Of those 37 million people you mention who are living with HIV, a third of them are not accessing antiretroviral therapy, and globally a million people died of AIDS in 2019 alone. Astonishing, and perhaps even more so because we seem to hear so infrequently about those numbers. I grappled with trying to address more explicitly in 13th Balloon how race and class and gender and geography continue to be factors affecting whether or not people have access to information and prevention and treatment, but I had to accept that that wasn’t what the book was trying to do.

This is the first sentence of Diana Vreeland’s memoir, DV: “I loathe nostalgia.” I’m with her, mostly, but part of the reason Later feels so immediate for me is that I’ve visited Provincetown many times since I was 19 or 20, and while I’ve never stayed longer than a week at a stretch, I find it life-changing and -affirming to be in a space where queerness is embraced—in fact, the cover image for 13th Balloon is a photo I took from the Provincetown ferry. Not to wax too sentimental, which you certainly don’t in your book, but one of the things I love about the place is that so little seems to have changed in 30 years. A lot of the same shops and restaurants are still there, not a Starbucks or Chase bank in sight. I realize that’s surface stuff, and of course there has been gentrification, but I still feel the same thrill visiting now as I did when I was young. My experiences there didn’t include the sense of peril and sadness yours did; I simply felt protected. If an illusion, at least a consoling one. And what a weird, sad paradox—when merely feeling safe is an unexpected thrill. Near the end of Later you write that some kinds of nostalgia are “murderous” and that “AIDS isn’t the good old days.” Was nostalgia ever something you felt you had to resist as you wrote the book, or was it not a temptation at all?

Lisicky: You’re definitely right that certain elements of Provincetown are still what they were 30 years ago: those dunes just as you’re approaching town, the density of trees between town and Race Point, the absence of chains (though there is a new CVS, which townspeople fought tooth and nail). And of course the safety that queer people feel instantly into their bodies—a kind of safety that I don’t associate with any other place, even though narrow Commercial Street can be pretty precarious in summer, with pedestrians and bicyclists and delivery trucks all competing for that insane one-way lane. When I first moved to town I remember how my body changed within a couple of weeks. I remember walking down the street with a kind of ease I’d never known anywhere else, holding my shoulders back. I was in my body, in a public place, for the first time in my life.

And yet, maybe because I lived in Provincetown year round from 1991 to 2006, I’ve seen changes too: the north Herring Cove parking lot lost to erosion in the last couple of years, Race Point Road reconfigured further inland so that it’s hundreds of feet from what used to be the shore. Also, houses along the harbor lifted high on pilings, even if they’re historical houses. So the marks of climate change are pretty visible, but the marks of big money have drawn and quartered up the town too. It’s an obvious thing to say, but money puts up walls, draws lines.

I could spend time talking about that, but I’ll just say that for me it isn’t the town that I first moved to, when people were too preoccupied with the daily stress of an epidemic to worry too much about status, whether we’re talking money or looks, etcetera. It was a young town, because men didn’t live past 40. It was a town in which people kept an eye out for one another, even if a lot of that was subtle—this was New England, after all. There was a lot of checking in, a lot of saying hello. Of course there were cliques, and that person might have loathed that person, but it was a place where people made an actual effort to make up community, day by day, as if it were a matter of collective art-making or justice-making—I can’t think of a better way to put it. There will always be a semblance of that urge in town. It’s not fair to talk about it in the past tense, but it was especially true in those bleak years.

I thrived on the all the colliding energy of that environment, but it would be awful to idealize those times, as all of that community-building was happening alongside, because of, this unspeakable illness that was decimating the town week by week. I, of course, felt the pull of that nostalgic wave as I was writing the book, and I thought it was important to resist it every time I felt it. There was lots of love, but that love came at a dire cost —and I think people who lived through those times, and even more recently, are still grappling with the psychic wreckage, not just of watching friends, family, and partners die, or dealing with homophobia, but of pure survivor guilt, which is its own crushing, continuous thing. What about you, and 13th Balloon? Did you feel the problem of nostalgia when you felt these poems coming into being?

Bibbins: I would admit to it if I had, but it didn’t feel like something I needed to resist or avoid—pretty much the only thing from the ’90s I’m nostalgic for is affordable rent. The content of 13th Balloon overall is sufficiently bleak that I suspect readers won’t see the book as nostalgic, but of course those perceptions are out of my control now. In Later you mention hearing someone use the phrase “trauma porn” to refer to “any book written about AIDS.” Nostalgia can creep in through the tiniest cracks in our writing—whether through syntactical choices or through overuse of what I call colorless amplifying words like “only,” “even,” “so,” “just”—but I don’t know how even the most diligent among us could get anything past the trauma porn guy.

A lingering cold currently has me congested, sneezing, coughing, tired. It’s early February in 2020 and stories about a global coronavirus outbreak are all over the news. The official death toll stands at around 700; cruise ship passengers are being screened and quarantined in Japan and Italy and Hong Kong and Bayonne, NJ; New Yorkers are starting to wear surgical masks on the subway (not many, but still). I know that’s not what I have, but a familiar what if flashes in my head every time I sneeze, much like it did in the ’90s. If I forgot to crack my bedroom window and woke up to find the pillowcase a little damp: night sweats. If I noticed a bruise on my shin and couldn’t remember bumping into anything: Kaposi’s sarcoma. If I felt some tenderness in my armpit while putting on deodorant: swollen glands, which could be caused by a litany of awful things. All of this was totally irrational—I knew how HIV was transmitted and that I hadn’t been exposed—but what if what if what if. Am I nostalgic for that feeling of low-grade, nonstop paranoia? Not in the least.

I was asked to contribute a poem to an anthology called Blood & Tears: Poems for Matthew Shepard, which was published in 1999. Shepard, for those who might not know, was a student at the University of Wyoming who was brutally murdered in 1998 for being gay. The story stayed in the national news for what felt like a long time, at least compared to the rapid-fire news cycles we endure now. The fetishization of the poet as some rarefied figure to whom readers turn for wisdom or comfort—a figure who could “make sense” of a tragedy like Shepard’s murder—has always made me anxious. I mean, there’s nothing wrong with readers seeking wisdom or comfort, but I think poets can run the risk of seeming smarmy, ghoulish, self-congratulatory if our response to tragedy is to play up that role—Okay everyone, I’ve got this—especially when we’re writing about a person we didn’t know. The poem I ended up making for the anthology was a collage that used phrases from sources I found online: news articles, interviews, police reports. It seemed like a method that would help me to avoid the trap of sentimentality, though when I reread it now the poem, despite being “impersonal,” seems rather poignant in its own way.

As serious as our books are overall, there are humorous moments in them. I’m thinking of a couple of sections in Later: “New Boy,” which describes the attention lavished on a certain type of attractive young man arriving in Provincetown, and “X-rated,” where you and a group of mostly straight friends have a porn-viewing party. Do you want to talk a little about the role of humor in your book?

Lisicky: Humor! I’m thinking of that moment in 13th Balloon when the speaker is on the beach in Fire Island, drinking after midnight: “Upon noticing in the distance headlights / bobbing in the fog I popped up and said no way / I’m forty same age as O’Hara let’s go let’s not / be this emergency again”—a reference, of course, to Frank O’Hara’s death by beach taxi in the same place. A few lines later: “I knew what it felt like / to be of a generation fully / accustomed to being struck down.” And the connection between those two points is significant. That moment in the Pines takes place seventeen years after Mark’s death, but the residue of loss is still fresh, and it’s captured by the irreverent humor as a means of survival, and the staggering awareness of scope. It seems reductive to put a label on those two positions—I keep thinking distance and closeness—and those words don’t seem adequate, but a conversation of seeing is implied. Those passages come from two different vantage points. And I love the tonal slide the poem enacts.

I’m glad to hear you mention humor in Later because one of my concerns is that it might go over some readers’ heads. In other words, if you think a book in which AIDS is prominent shouldn’t have humor in it, you’re not going to let yourself hear it. I didn’t expect humor, or plain silliness, to turn up in the book, but it wanted to be in the room apparently. Not simply as a point of relief but because jokes were there. It was how people bore up under the absurdity and awfulness of sickness and death. It was how people took care of one another, though no one would have stated it as such back then—that would have sounded sentimental. Humor was of a piece with dread; they were one organism; it never felt like they were characters on opposite sides of the room.

But the trauma porn guy—he’s the ice cube in the room. He’s the one who makes any kind of representation problematic. What art could bear up under that lens? Of course he probably he needs to hold on to that—is cynical too harsh?—position in order to leave the lunch with his friend and hook up with somebody at one in the afternoon—not that there’s anything wrong with that. And who knows if that statement conveys the full range of what he feels, or whether he’s trying something out. Maybe it’s a pose—a stance of aloofness that helps him get through the minutes socially. As I was writing Later I became interested in asking questions about the management of feeling. Is that management a trait that some of us develop unconsciously (or consciously) as a coping mechanism against a culture’s homophobia? Can there be a cost to getting to be a champion at that? And how might that aloofness get in the way of our ability to be intimate with anybody? Not just lovers but friends.

I don’t know. Big questions. I’m thinking about your lingering cold, and the prospect of the coronavirus in the air, and how it’s summoning up decades of constant low-grade paranoia about my own health and the health of others—why isn’t that little red bump on X’s shin healing? Anyway. I was wondering if what I’m saying about the management of feeling makes any sense in regard to how any of the poems in 13th Balloon took shape. I suppose this question is linked to the fear of nostalgia question. I just came across a quote from Hanif Abdurraqib in which he says: “[I’ve] known people completely eaten alive by the hoarding of sacred emotion.” Can writers be too fearful of feeling in their work? Is there a particular poem in the book in which you feel like you’re in confrontation with that?

Bibbins: Your idea of humor being “of a piece with dread” nails it precisely for me in this context, because when I found out about AIDS I was around 14 years old and the news was accompanied by a torrent of jokes. It seemed like they were everywhere. Obviously much of this joking was cruel and homophobic, but it also reflected an anxiety about sexuality in general and fears of transmission that were at that point unresolved, and probably still are for a lot of people. Remember Eddie Murphy’s routine about a woman kissing her gay friends and unknowingly infecting her husband? When he receives the diagnosis he protests, saying he’s “not a homosexual,” and the doctor responds, “Sure you’re not a homosexual.”

Of course that’s a much different use of humor than yours or mine in our books. Context is key. I don’t necessarily disagree when people call humor a defense mechanism, but it can also sound a little reductive and dismissive to me when it’s categorized as merely that—I see it as a source of power and strength, a way to maintain or reclaim agency in some way. It’s sort of like owning the word “queer”: that’s our word and we’re going to celebrate it and you can’t use it to marginalize us. Your jokes can’t harm us—in fact, we’re going to go further and darker and be even funnier.

Regarding the management of feeling, yes, it was something that was on my mind, not so much when I was writing the individual pieces, but when I saw the manuscript coming together later on. When I stood back from it I found myself surprised at the number of moments that I thought of as gut punches and I briefly wondered if there were maybe too many of them, if people would read the book and think I was trying be manipulative or “shocking.” But again, we can’t really control responses like that, and anyway I thought, no, dammit, that’s what those experiences were like for me and I’m not going to shy away from them. In my previous books I think I was interested in transforming experience through language; this time I was going for something more raw and unvarnished, not “truer,” but more immediate and, I guess, more accurate. I hope this wasn’t, at least on a subconscious level, internalizing critiques about linguistic extravagance that often read to me as vaguely homophobic. If it was, it resulted in what’s probably my “gayest” book yet, so there.

Back to the trauma porn guy—him again! You asked if I think “cynical” is too harsh a word for his position, and I don’t really. Not that I disagree with your assessment, but that I don’t see the designation as harsh. I mean there’s a kind of cynicism in, say, politics, that is truly ugly and destructive, but I’m for keeping the word “healthy” in front of the word. Maybe cynicism is just another defense mechanism, with or without the modifier. But do you think there can be a healthy version of it in art—your own or others’—a strain that’s more nuanced, that we should preserve a space for now, even though the generations coming up may seem more earnest? Perhaps cynicism today is better suited to music than poetry or memoir? Radiohead does it pretty damn well.

Lisicky: Definitely—and I’m thinking too of Leonard Cohen, whose work I taught just yesterday to my undergrads as part of a class called “The Singer Songwriter.” I thought I’d have to work hard to sell them on Leonard Cohen. I thought they’d find him too jaded and gravelly and wouldn’t engage. I was listening to “Avalanche” in prep the other night, then “You Want it Darker,” and thought no, no, no—they’re going to hate what I’ve done to them. But in truth those 19-year-olds got Leonard Cohen’s healthy cynicism much more than they did many of the songs from Joni Mitchell’s Hejira, which we’d talked about the previous week—songs in which the speaker aims to process the darkness out of herself. (“I see something of myself in everyone / just at this moment of the world.”) Leonard Cohen, on the other hand, is attempting to claim darkness, jadedness, cynicism, over and over again, and he wants to walk with it, because he knows there’s no other way out of this life. It’s intertwined with his holy streak, and my students understood it in a way they didn’t get Joni’s inquiries toward emotional health or growth or whatever name you want to put to it. Maybe that understanding comes from being 19 years old in an age of ugly and destructive politics. All in all, it was an oddly exciting class, and I think I learned something big from our discussions.

As to whether that cynicism is still possible in literature? I’d say yes. I’m thinking of Thomas Bernhard or Philip Larkin. Some might put Joy Williams’s 99 Stories of God under that roof too—and Robinson Jeffers. But the cynicism in Williams and Jeffers is really about humans, the hell we’ve wrought on Earth. It’s definitely not about the animals or the land, which are always associated with purity, divinity.

I think my wiring is probably more Joni than Leonard, but that doesn’t mean one’s wiring doesn’t change over the course of a life. I tried to scatter many moments of that cynicism throughout Later—and simply leave them on the page, without apologizing or buffing and shining. I’m thinking about that moment when the speaker is walking down Pearl Street and thinking about how winter has gotten the best of the town, scoured it raw and ugly, and he says, “Do you realize how ugly this place is?” Which is, of course, Provincetown sacrilege. Or every mention of God’s abandonment, especially of the sick. Or: “Imagine trying to look at God, and if you think you can do that, God will find a way to break you.” I know exactly what you mean when you say healthy in this context. How could we even begin to write about this period—or any subject, for that matter—if all we saw was light?