Dr. Karen Frey is a geographer—specifically, a polar scientist who studies the effects of climate change on Arctic sea ice. Travis Ryan is the lead singer of one of the most extreme metal bands of the modern era, the aptly named Cattle Decapitation. While Dr. Frey spends her field seasons on scientific expeditions to the northern oceans—some of the most unforgiving environments on the globe—Travis Ryan tours the world with a band known as much for its brutal sound as for its radical political messages.

Despite these differences, the scientist and the frontman have found themselves pursuing parallel intellectual challenges, albeit from distinct perspectives. Using different tools, and through different media, both seek to map the realities of climate change and in so doing, communicate the magnitude and urgency of the global climate crisis.

For the past several decades, both scientists and artists have done their part to sound the alarm about a looming socio-ecological catastrophe. This is the age of the Anthropocene, a new epoch defined by the presence of human activities in the geological record. Academic debates about nomenclature aside, the notion of the Anthropocene is powerful: it implicates humans directly in the cascading impacts of global climate change. And while neither the sciences nor the humanities offer simple solutions to the complex challenges facing humanity and the planet, both fields have an essential part to play in achieving the kind of social and political changes necessary to avoid a dystopian future of our own making.

In early December, I met with Dr. Frey in her office at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, where I am a graduate student in the Department of Geography. It was a cold day, and bundled-up queues of students shuffled to class along semi-plowed trenches of snow, the result of an unseasonable storm. Above them, juncos and nuthatches crowded the bare trees, with free rein now that the fall migrants had moved south, a bit later than usual.

My conversation with Dr. Frey began casually, but as with most discussions about climate change, it soon crossed into existential territory. “The Pacific Arctic region where I study—the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Sea around Alaska—the unraveling that has occurred up there…” Dr. Frey trailed off, searching for the right visual aid to communicate what her years of field observations and research have helped her to understand intuitively. “You have all these really important linkages between all these systems, both physical and ecological. Once you start unraveling that tightly-woven sweater, it undoubtedly starts to unravel the entire system.”

Dr. Frey studies polar regions in part because of their aesthetic appeal, drawn by an explorer’s zeal for rugged and expansive landscapes. But these areas are also incredibly valuable from a scientific perspective, representing useful indicators of a changing global climate. To those who know how to read the signs, the rapidly changing Arctic is seen as a harbinger of things to come.

I asked Dr. Frey to tell me what this looks like. “Undoubtedly, one of the most profound changes that we will see in our lifetime is the disappearance of the perennial sea ice pack in the Arctic Ocean,” she said. In other words, the latest scientific models indicate that the North Pole of our collective Arctic imagination will begin to vanish for months at a time by 2040. By 2060, the Arctic will be ice-free for the entire summer.

Dr. Frey might have chosen one of many technical examples, like large-scale species die-offs, a potential result of harmful algal blooms, themselves a byproduct of warming seawater temperatures. Or increasing melt events that trigger positive feedback loops, which accelerate sea-ice loss. But as she explained to me, she’s found that the image of a blue Arctic—an expanse of open water where we have come to expect ice—hits lay audiences particularly hard, so she uses it often.

“When you look at a map or a globe,” Dr. Frey continued, referring to several examples hanging on her wall, “you are always imagining that white polygon around the North Pole. But that will cease to exist in our lifetime.”

My eyes came to rest on a polar stereograph, hanging on the wall between pastel paintings of arctic fauna. The map is a projection of Earth, looking down on the North Pole from somewhere out in space. From this vantage, the continents revolve around a bleach-white expanse whose borders, like no nation on Earth, are constantly renegotiated by seasonal flux. This cartographic feature is not land, but frozen water; when the ice disappears, its borders will collapse.

The implications of such large-scale sea-ice change are manifold. Physically, reducing sea ice also reduces the albedo-cooling effect that this bright ice pack produces for the planet: by reflecting more sunlight than seawater, it helps to regulate global temperatures. Ecologically, loss of sea ice threatens animal species that rely on ice pack for their subsistence, such as the iconic polar bear. Psychologically, this extent of sea-ice loss reshapes our image of the Earth, transforming our vision of it and ourselves. The effect is alienating, to literally make us feel alien (read: extra-terrestrial, in which terra is Earth, but Earth as we know it is gone) on our own planet, the only home any of us have ever known.

“The sense of urgency has always been there for scientists; I just think we’ve gotten better at communicating it,” says Dr. Frey. “But how do you convey urgency and hope simultaneously?” I’m not sure if it is a rhetorical question, but I let it hang in the air anyway, having no immediate reply.

Across the philosophical spectrum, Travis Ryan of Cattle Decapitation echoes Dr. Frey’s sober perspective on the urgency of the climate crisis. For Ryan and his bandmates, this sentiment has translated into an impressive discography of conceptual albums that cover a range of themes, from radical calls for vegetarianism to more recent work that engages directly with global climate change. Many of Cattle Decapitation’s albums feature gruesome cover art in which dark, bloody satire is used to expose the hypocrisy latent within the humanistic norms of liberal capitalism.

Cattle Decapitation’s 2015 release, The Anthropocene Extinction, was met with critical acclaim. It was the first of their albums to confront the Anthropocene by name. For their 2019 release Death Atlas, the band took their conceptual game to another level. Musically, the album builds on Cattle Decapitation’s ever-evolving sonic repertoire, which sits somewhere among a number of metal subgenres, including black metal, death metal, and grindcore. To complement the music, the band teamed up with visual artist Wes Benscoter to produce an ambitious and cohesive artistic project fixated on climate change and the Anthropocene.

Accompanying the album is a short film entitled The Unerasable Past, in which viewers are treated to Benscoter’s apocalyptic visual art. In the film, a ravaged landscape of sculpture and ruin is set to a soundtrack of languishing metal and Ryan’s signature blend of guttural growls and polyphonic screams.

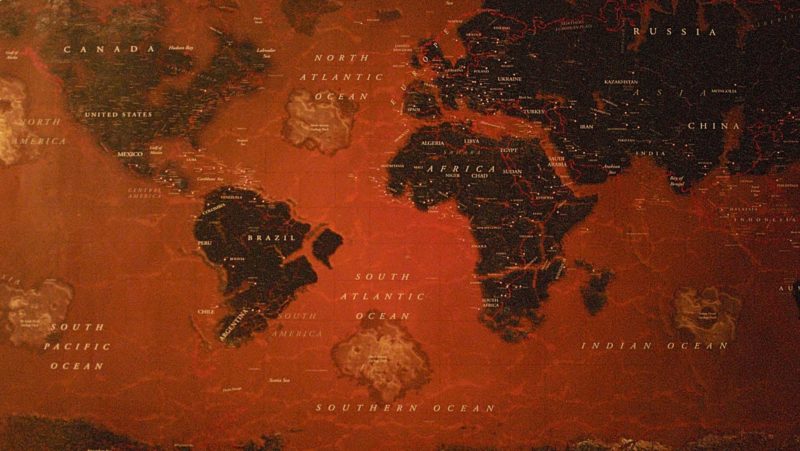

Also included with Death Atlas is the Post-Anthropocene Map, a 42-by-64-inch vision of our climate-ravaged future projected onto the surface of the Earth. While the map itself is an artistic interpretation, the process for making it was not without scientific input and considerations. As Ryan explained in a recent interview for Loudwire, “With this record, I really delved more into hard facts and metaphors for a little more of a poetic attack at talking about climate change.” According to Ryan, the band landed on the album’s central conceit—the overarching map/atlas metaphor—because it struck them as a powerful perspective from which to confront a global issue like climate change, and one that would also resonate with their audience.

The vision of the world depicted in Cattle Decapitation’s Post-Anthropocene Map is not an optimistic one: it shows climatic dystopia on a global scale. In the map, the familiar contours of our puzzle-piece continents have been disfigured by rising seas. Australia-sized islands of garbage whorl at the center of all major oceans. And, as if to reflect Dr. Frey’s research, the white polar polygon has been replaced by an expanse of open ocean. But unlike Dr. Frey’s blue Arctic, on the Post-Anthropocene Map the ocean that takes the place of the vanished ice is the hue of stagnant rust.

Cartography—the making of maps—is among the most ancient human creative activities, simultaneously a craft of art and observation. Maps are always partial and selective in what they include and what they omit, leaving much up to the discretion of the map-maker. As symbolic representations of complex social, cultural, political, and ecological systems, they reveal as much about the places they depict as they do about the people who create them. Despite these limitations, maps remain incredibly powerful tools for producing a synoptic view of our planet.

I remember opening J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit for the first time when I was young, the worn binding of the old book flopping open to reveal a foldout map of Middle Earth. Within the map, the geographic landscape of the story was laid out before me, wrapped in a mythical, acrobatic calligraphy. The effect was at once intellectual and emotional, conveying a sense of understanding as well as one of wonder. This experience is a shade of a much broader socio-psychological phenomenon known as the “overview effect.”

First described by astronauts looking back on our “pale blue dot” floating in the cosmic void, the overview effect is a cognitive shift caused by a radical change in our perspective on the Earth. As Dr. Frey explained to me, reflecting on her own past ambitions of space travel, “[For many astronauts] the philosophical awakening came not from looking out into space and considering the yonder, but instead looking back at their home as a cohesive element.”

The overview effect is not restricted to those who have ventured into orbit. The indeterminate, overwhelming feeling evoked by an immense landscape produces a similar sense, as does staring out the window of an airplane at the patchwork world below. Any experience that dwarfs the human scale and radically changes one’s scalar perception has the potential to produce a flavor of the same overview effect.

The universality of the overview effect, as well as its ability to strum the chords of human reason and emotion, has implications for communicating science, as Dr. Frey knows all too well. Through Earth visualization, including the making of maps and models from satellite imagery, Dr. Frey attempts to communicate the magnitude and urgency of her research by dramatically shifting the spatial scale of perspective, thereby simulating a sort of virtual overview effect for her audience. Cattle Decapitation’s Post-Anthropocene Map does the same thing for listeners.

The overview effect can be the product of warping not only space, but time. According to filmmaker Jeff Frost, who uses time-lapse video to tell the story of climate change-induced wildfires in California, the shifting of “temporal chronologies” can have much of the same effect as shifting spatial ones. In his latest documentary, California on Fire, Frost speeds up and slows down footage of wildfires, disrupting normal human time frames, allowing the realities of climate change to sink in on an emotional and intellectual level. It is art, and it is beautiful, but it is also conflicted, its beauty belying a terrible physical and psychological trauma. The effect is awful in the most literal sense of the word—that is, full of awe.

Cattle Decapitation’s unique blend of musical styles is awful in the same sense, producing a sonic equivalent to Frost’s shifting temporal chronologies. This is nowhere more evident than at a live show.

Later in the evening after I talked to Dr. Frey, I found myself at a small, packed venue outside Boston. Several opening bands offered an appetizer of heavies and sturdy breakdowns, but the main course was Cattle Decapitation, whose black scrims bookended the stage. As the last opener retired, leaving their amps crackling with feedback, the room was static in anticipation.

Cattle Decapitation’s set began with a track of ominous atmospherics, which settled over the room like dark clouds. Over the ambiance, a monotone voice intoned, “The recent unparalleled temperatures in the Arctic as well as the data showing abnormal rises in upper-atmosphere methane levels converge to give the impression that the near future of the entire human race is at stake.” A mournful piano joined in.

The voice went on: “In 2018, the World Bank group reported that many countries will need to prepare for over 100 million displaced people, as well as the displacement of millions of international refugees, due to the ill-effects of climate change. It has become clear that an enormous operation and policy program to revolutionize agriculture and repair the earth’s ecosystems is immediately needed.” There was a sense of being suspended in time, the fate of the entire planet looming before us. The black walls felt like a vice, trapping the room between these visceral statistics and a hopeless oblivion, ready to erupt.

And then the band kicked into the title track off their new album, thrusting the crowd against a wall of thrashing guitar from Josh Elmore and Belisario Dimuzio, buttressed by blast beats from drummer Dave McGraw and a percussive spine provided by bassist Olivier Pinard. Ryan stood at the altar of the stage, issuing demonic decrees over the distorted chords and incessant double-bass: “Alas, the deed is done / Mankind now dead and gone / Post-Anthropocene, Earth reset to day one / Fire now rages on.”

After barreling through several speedy bridge sections, the lights shifted and the song dropped into a cymbal-laden breakdown. Ryan’s vocals mutated into a slow and monstrous growl, the impact as heavy as the sun. “We deserve everything that’s coming,” he sang. “We took this world to our graves / We made its creatures our slaves / Shattered the hourglass / An un-erasable past / Humans, demons deranged and depraved.”

Musically, such manipulation of tone, tempo, and time signature create a turbulent and visceral experience for the crowd. With each change in the music, a mosh pit at the center of the floor responded in kind, a writhing sea of long hair and limbs and black clothes reacting like a single organism. Heads banged in unison. Arms and legs flailed like grasping cilia. If one body fell, others moved to pick up the fallen comrade.

To some, Cattle Decapitation might sound brutally heavy, but otherwise comparable to other bands in the extreme-metal scene. Other fans are drawn to the band because of what sets them apart: they are, explicitly, a voice for the existential fears of the Anthropocene. Playing live, they create a social space that serves as a much-needed outlet for simmering feelings of alienation and despair—feelings built into many subcultures, but to which the overwhelming reality of climate change has given new shape. By envisioning these fears, by giving them a name, Cattle Decapitation attempts to reclaim some power over them.

The compressed music hall smelled like sweat, and I felt the temperature of the room steadily rising. The experience was hectic, equal parts mesmerizing and terrifying. At times, it was even transcendent.

By merging the power of dystopia with the perspective of the overview effect, Cattle Decapitation levels a vicious satire at the utopian and modernist imaginaries that have led us to the precipice of climate disaster. But while their vision of the future is apocalyptic (a theme and aesthetic common among other metal bands) their artistic work is inspired by genuine feelings of helplessness and despondency at the state of the world—feelings that are widely shared, not only by those who listen to metal, but also those that do not.

This sense of solastalgia, an existential sorrow caused by environmental change, is a symptom of the Anthropocene. In this brave new world, we experience global change on a personal level, with geologically-scaled events occurring within the timeframe of a human lifespan. We can see and sense and feel it happening, and as a result, each of us is forced to confront the radical warping of our own perception of time and space, and our place within it. And while the impacts of climate change are unequal, affecting the most vulnerable to a disproportionate degree, there is an element of universality in the global proportions of the climate crisis. Spaceship Earth.

In this sense, the phenomenon of the overview effect seems built into the architecture of the Anthropocene. Should we choose to pay attention—as Cattle Decapitation’s music and Dr. Frey’s research implore us to do—the power of the overview effect might be leveraged as a strategy for keeping our earth systems in check, producing in aggregate the sort of social tipping point we need to turn the corner in the fight against climate change. The only question is whether such social thresholds will be reached before our Earth’s systems reach their respective biophysical thresholds.

“It might take death, unfortunately. It might take destruction,” Dr. Frey said soberly, as she wrestled with these blunt estimations. “But hopefully, those social tipping points will happen sooner rather than later, such that we avoid those things.”

I left the show and walked the few blocks back to my car, hands tucked deep into my pockets, braced against the cold. It was quiet in the city, and after the chaos of the concert, I felt dizzyingly alone, my head in orbit. As the intensity of the concert drained away along with my body heat, I was filled with a familiar creep of dread, as if the ground might open up and swallow me whole. Leaning into the existential maw for too long will take its toll.

I reached my car and slid the key into the ignition. The engine turned and caught, rumbling to life as an invisible stream of carbon dioxide was sent skyward. Hardly for the first time, I wondered what I should make of this personal paradox: raging against a thing in which I myself am implicated. My drive home would be icy and dark.

Earlier that afternoon, toward the end of our conversation, I’d asked Dr. Frey whether she was an optimist. I had posited the question for my own sake, but not without genuine curiosity.

“I think you have to be,” she replied without skipping a beat, a glint in her eye that struck me as rebellious. “My hope comes from the fact that this problem is too big, it is too real, to not be dealt with.”

I felt bolstered by her response, even on the doorstep of such a hollow winter evening. My ears were still ringing.