Will recent advances in human tissue preservation change the way we think about bodies, death, God… and China?

Photograph via Flickr by Swamibu

Photograph via Flickr by Swamibu

Questions concerning the ethical treatment of the dead have been with us at least since Sophocles, for whom a single act of leaving a corpse unburied brought mayhem that threatened the stability of society. In Antigone, the punishment King Creon gives to the murdered Polynices is so severe that it extends beyond the limits of life. According to Polynices’s sister Antigone, death is only the beginning of the torments a body can face: “As for the hapless corpse of Polynices, it has been published to the town that none shall entomb him or mourn, but leave him unwept, unsepulchred, a welcome store for the birds, as they espy him, to feast on at will.”

For Sophocles, to leave the dead unburied is an insult not just to the deceased or his family, but to the gods. That proper treatment should be given to human remains, Antigone insists, is among “the unwritten and unfailing statutes of heaven.” She defies the state and risks her life in the attempt to see these statutes carried out, and calls upon others to do the same, even asking her reluctant sister, “Will you aid this hand to lift the dead?”

Corpses have always been commodities—even Saint Augustine complained of entrepreneurial monks roaming the countryside “hawking the limbs of the martyrs.”

It’s difficult to imagine how Antigone’s plight might play out today. For those with the savings or the life insurance settlement to pay for it, there are any number of ways of dealing with human remains that are considered acceptable, and in every case the state requires, rather than prevents, some form of timely and permanent removal. Burial, cremation, resomation, organ donation, “whole body gifts” to science; all have become legitimate options. Although it is common for the preferred means of disposing of an individual’s remains to be stated before death, often the method is chosen by the family of the deceased. In either case, there are few ethical concerns. Though a corpse has no autonomy, the treatment it receives, if carried out in accordance with specified wishes, can be seen as the last act of the will.

In just the past few years, however, new concerns have begun to arise concerning what it means to treat the dead ethically, and whether or not it is even possible to do so. Advances in technologies of tissue preservation—from cryogenics to chemical reduction to the injection of silicone polymers at the cellular level—have introduced unprecedented possibilities for the uses of human cadavers just as global markets have opened apparently limitless sources of bodies, creating tissue processing industries that never before existed. Corpses have always been commodities—even Saint Augustine complained of entrepreneurial monks roaming the countryside “hawking the limbs of the martyrs”—but never before has both the supply and the demand been so great.

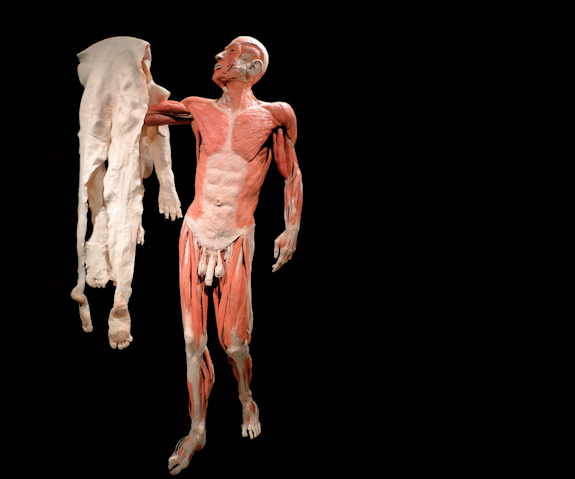

Nowhere is this more apparent than in a wildly popular anatomy exhibit currently touring the world. “Bodies… The Exhibition” is a for-profit traveling display of human cadavers that have been treated with a process that plasticizes tissue, allowing them to be manipulated and viewed in various states of artful dismemberment. Ostensibly the exhibition is scientific and educational in character, but given that there are no longer many mysteries within human anatomy, the most pressing questions it raises are ethical: Is posing a dead man with a tennis racket wrong? Is a failure to make specific provisions for the treatment of one’s remains the same as giving one’s body to science? Does the education offered by an anatomy exhibit offer the same kind of public good as organ donation? To put all this in the simplest and starkest terms: What are the dead for?

The use of humans as material is rarely simple or stark, however. “Bodies… The Exhibition” is produced by a Georgia-based company primarily for American and European audiences, but the human remains featured have come exclusively from the People’s Republic of China, a nation and a culture that has its own history of ethical and religious reflection on the body. With this in mind, it must be asked if the questions such displays raise—questions that seem to Western audiences to arise naturally—are the appropriate questions. There are any number of ways in which Chinese notions of death differ from those held by Europeans and Americans. So whose conception of the body matters more, that of the Western living or the Eastern dead?

In every one of its scores of appearances, “Bodies… The Exhibition” has begun with a disclaimer. The exhibit about to be seen, a small placard reads, is in no way related to its chief rival in the world of anatomical exhibitions, “Body Worlds”, or to other works conceived and managed by “Body Worlds” founder Dr. Gunther von Hagens. The genealogy of these two anatomical education franchises, and the resulting competition between them, is inseparable from the ethical questions raised by each.

Von Hagens, a German physician turned entrepreneur and showman, is not only the originator of this new form of anatomical education, he is also the inventor of the process that makes it possible. Both “Bodies… The Exhibition” and “Body Worlds” make use of a new technology von Hagens calls “Plastination,” by which all water is removed from human tissues and replaced with soft silicone polymers. (“Bodies… The Exhibition,” it should be noted, uses the term “polymer preservation” to describe an identical process. “Plastination” as such is patented and trademarked by von Hagens for specific use of “Body Worlds” and its affiliates.) A macabre detail included in the story von Hagens tells of the development of this process hints at the ethical questions that were to come: He first thought of creating perfectly preserved cross-sections of human bodies when he was at a sandwich shop one day watching a butcher run a ham through an electric slicer. It was a flash of inspiration that foreshadowed the dehumanization of the bodies that would follow, for after the Plastination process is complete, von Hagens no longer calls them dead bodies, or corpses, or cadavers, but rather “plastinates.” (“Bodies… The Exhibition,” again, uses an alternate term, preferring the untrademarked but equally impersonal “specimen.”)

Terminology aside, the exhibits are nearly indistinguishable. Filled with displays of human remains that clearly required as much artistry as technical ability to construct, each presents an average of twenty full corpses and hundreds of other disembodied parts arranged in a manner suggestive of a life-sized, three-dimensional anatomy text book. In each exhibit, corpses are made to throw footballs, stand on balance beams, even dance with their own entrails. The source of this similarity is neither an accident nor a mystery: “Bodies… The Exhibition” was founded by a former employee of von Hagens.

The main difference between the exhibits, it turns out, is ethical. More precisely, it is a matter of differing levels of attention to the practice, and the rhetoric, of ethics as it applies to the treatment of the dead. “Body Worlds” goes to great lengths to explain that every one of its “plastinates” was the willed gift of an individual, mostly from Europe, who had pre-arranged to donate his or her body for the use of scientific study or education. “Bodies… The Exhibition,” on the other hand, makes no such assertion. It acknowledges that its bodies come exclusively from China, and that they had formerly been in the possession of the Chinese government because they had died in hospitals with no kin to take responsibility for their disposal. As chief medical adviser for “Bodies… The Exhibition” Dr. Roy Glover told National Public Radio, “They’re unclaimed. We don’t hide from it, we address it right up front.”

Von Hagens, by contrast, is a tireless promoter of the ethical difference between his exhibits and the others. “All the copycat exhibitions are from China,” he told the New York Times. “And they’re all using unclaimed bodies.”

His exhibition has been gaining attention by holding gatherings for those so taken by his process that they have been moved to sign up for Plastination themselves. After joining a donor list von Hagens claims includes seven thousand names, would-be plastinates must fill out a form that keeps the terms of their donation open-ended in some respects (one can cancel one’s donation at any time), but frighteningly specific in others. The matters of agreement range from the practical (“I agree that laypeople be allowed to touch my plastinated body”) to the aesthetic (“I agree that my body can be used for an anatomical work of art”) to the ontological (“The body donor’s own identity is altered during the anatomical preparation”). With each granting of consent, donors assert that autonomy extends beyond the end of life. They may not know precisely what pose they will find themselves in for eternity, but in choosing their methods of disposal, they do know they will never be unclaimed. In a sense, they have preemptively claimed themselves.

Claiming, it turns out, is a crucial element in understanding the ethics of the dead. It is perhaps equally important in both the culture in which the bodies are displayed and the culture from which they have come. However, there is a significant difference in each culture’s ethical assumptions about who has the right to do the claiming.

To the extent that any single set of ethical precepts guides Western attitudes toward the treatment of the dead, it is undoubtedly Christian teaching. Roughly 75 percent of Americans are buried when they die (rather than disposed of by some other means), and though changes in religious opinions like the recent acceptance of cremation by the Roman Catholic Church are sure to alter that percentage slightly, it is unlikely that the cultural disposition toward burial will disappear any time soon. The main reason for this preference seems to be not that anyone relishes the idea of lowering a loved one into the ground, or of being so lowered oneself, but rather that there is widespread acceptance of the notion that, as summed up nicely by Baptist theologian Dr. Russell D. Moore, “For Christians, burial is not the disposal of a thing. It is caring for a person… The body that remains still belongs to someone, someone we love, someone who will reclaim it one day.”

In the Christian conception, the resurrection of the dead is not just a belief in a future event; it’s a reality that has immediate implications. The fact that the body “belongs to someone” who will “reclaim it someday” removes the remains of the dead from the category of that which must be disposed of, and places them in a category closer to valuables that must be safeguarded for their owner’s eventual return. In other words, the belief in the resurrection of the dead is a de facto declaration of enduring ownership of the body by the person who has died. Because the body does not lose its personhood, it remains its own possession.

However, as in Antigone, ownership is not the only factor to be considered. If scripture is viewed as the Christian’s primary ethical guide, treatment of the dead is derived, at least in part, from divine command. The first biblical burial is depicted as an almost automatic act with the ground opening its mouth to receive the blood, and presumably the body, of the murdered Abel. Thereafter, it is always one human who buries another. First there is Sarah’s burial mentioned above, then that of Abraham, whose sons laid him beside his wife. Later, Rachel dies and Jacob sets a pillar on her grave. When it comes time for Jacob to die, he makes it clear whose wishes are to be followed in the disposal of his body:

Bury me not, I pray thee, in Egypt. But I will lie with my fathers, and thou shalt carry me out of Egypt, and bury me in their burying place. (Gen. 47:29)

Throughout the Bible, bodies are buried in the proper way and place because God finds the alternative shameful, and also, often but not always, because to do so is the preference of those who have died. The underlying notion in all of this is that the body is a gift that has been given by God to a specific individual. Though in death God relieves the dead of the burdens of the body, God does not rescind ownership.

The lack of oversight by either government or medical authorities in China has allowed the body processing market to boom in recent years.

Obviously, Christian notions of appropriate treatment of the dead do not apply to all who die in a secular and diverse society, regardless of its particular religious history. However, it does seem that certain elements of the Christian approach to the dead have carried over into the secular realm—specifically, the belief that there is ownership and free will even in death.

So it stands to reason that any viewers who suppose that the final destination of their own bodies will be their choice, may also suppose that any body they view under the bright lights of an exhibit hall has chosen to be there as well. Consciously or not, we want that to be the case. The alternative would be that we are seeing a display of bodies that tells us that our conception of being dead—that there is any kind of choice involved—is self-delusion. It’s difficult to imagine that a different assessment of being dead might be made in the place where the “specimens” lived and breathed and, after dying, were transformed into objects for our benefit.

The lack of oversight by either government or medical authorities in China has allowed the body processing market to boom in recent years. Even von Hagens, who protests that “his” bodies are of European origin, processes all the human remains for his exhibitions in China. Cases have been cited of bodies discovered on farms, kept on ice, and destined for Plastination factories in the coastal city of Dalian. Doctors and medical students from Chinese universities, which are in every way complicit, admit that they have no idea from where the bodies on which they work have come. If press reports are accurate, these medically-trained professionals seem little troubled by their work.

It would be easy to blame globalization for this situation. After all, the Western desire for Eastern bodies is nothing new, and a newly-opened China has the most Eastern bodies of all. Precedents for this interpretation are easy to find: As recently as two years ago, European museums ran into their own dilemma involving the ethical treatment of the dead when it came to light that a number of major institutions still held collections of disembodied Maori heads sent home by French and British adventurers in the nineteenth century. The elaborately-tattooed heads, known as toi moko in the Maori language, had been removed from bodies and remarkably well preserved by the Maori themselves. A further level of complication arose when it was determined that a number of the heads were not in fact of Maori origin. They were, it seemed, the heads of members of other indigenous peoples of the South Pacific who had been captured, tattooed, and decapitated specifically because of the booming toi moko market on the other side of the world. Certainly the Plastination of anonymous Chinese for display in North America has echoes of this unfortunate history.

However, it may be the case that there is another factor at play here: an ethical foundation to the Chinese body industry that has not been explored. As in the Western context, the key to understanding the particular ethics of the dead involves examination of the rituals of burial. In a study of Chinese mortuary practices, Sacramento State University archaeologist Wendy Rouse notes that the spiritual underpinnings of dealing with the dead are not so easily unpacked as in Christian and formerly Christian lands: “The development of the three major religions of China, Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, significantly influenced the evolution of Chinese death rituals and beliefs,” she writes. “Over the years, these philosophies became so intertwined that it is now difficult to determine which religion influenced the death ritual.”

Although the origins of many of its components are difficult to identify, the Chinese ritual, like Christian burial, is a practice hundreds of years in the making. Its variations are endless, but in every instance the ritual does rest on the highest of Confucian ideals: honoring the ancestors. Every act of the ritual seeks to increase the comfort of the dead and to ease his or her way into the world to come.

The division of the body and the soul is generally taken to be a Western dualism, but a similar concept can be found in Chinese belief. This is not a body/soul divide in the usual sense but rather a division of the soul itself into two principles known as the hun and the po. The first of these, the hun, refers to the spirit and the intellect of a person, whereas the po makes physical action possible. As Rouse explains, “At death, the hun separates from the body and ascends to the realm of immortal beings, while the po remains with the body.”

It is to the po, then, that the rites of death are directed. These rites include such elements that would seem familiar in the Christian context like prayers and the cleaning and dressing of the body. In fact, the attention paid to the dead is far more elaborate than that required by the Catholic Church. One of the original purposes of fengshui, which in the West usually refers to nothing more important than the arrangement of furniture, was the arrangement of the dead. Even one thousand years ago, it was a common practice to hire experts to make certain that a grave was properly oriented for the maximization of positive energy. As Rouse sums up the practice in the following passage, the first use of “deceased” refers to po whereas the second refers to hun:

The living could help the suffering of the deceased through chanting of incantations and burning offerings of food, money, and clothing. Once the deities in the netherworld received these appeals, the deceased could be granted a reprieve.

On the face of it, this does not imply an ethics of the dead very different from that which is suggested by Christian rites. The body is not merely a shell; it is a spiritual component of a person. For that reason, it must be treated with respect. However, the ethics involved shift when we consider the additional reasons for the undertaking of the rites of the dead:

The descendants considered the comfort of the deceased ancestor of utmost importance. If the po soul remained comfortable in the grave, the living would reap the blessing of their contented ancestor. Failure to provide for the deceased could result in punishment in the form of bad health, poor harvests, or a variety of calamities.

In the Chinese religious and cultural context, burial is an act performed not only for the dead but for the living. The same may be true in the Western context, but here it is much more explicitly built into the ritual’s performance—and for that matter, its nonperformance. Unlike in Christian rhetoric of dealing with the dead, in the Confucian framing of the subject it is not assumed that everyone has the same rites awaiting them. All humans are not equal in death.

“The men of the family, especially the heads of the household, received the most ceremony at their death,” Rouse explains. “Unmarried adults and young children received little, if any, attention. A person without descendants was simply placed into a plain wooden coffin and buried anywhere a gravesite could be obtained. Graves of convicts were dug in rows with no attention to the positioning of the graves according to the principles of fengshui.”

In death as in life in the Confucian context, humans are valued based on their kinship connections. To be the patriarch of a large clan is to know that in death one’s body will be celebrated and treated well. A fengshui expert will be brought in to make certain there is the right balance of energy in his final resting place. Prayers and offerings will be made before and for weeks after the funeral so that his hun may depart to eternal life and his po will rest in peace. As one traditional funeral chant makes clear, the dead are being constantly apprised of the ritual actions taking place on their behalf:

We are now cleansing your face

The more your eyes are rinsed

The brighter they become

We are now cleansing your body

The more your eyes are rinsed

The brighter they become

We are now cleansing your hands and feet

When cleansed, they will feel so very light

To perform acts of respect toward the po but not to let the hun know about it is to risk the ritual going unnoticed. Such a situation invites the lingering presence of the spirit of the dead. Though the dead are revered, their continued influence is something to be avoided at all costs.

Through all this ritual action, the deceased is naturally the focus and the most pressing concern. However, it must be remembered that the underlying reason for the ritual is that the comfort of the dead is necessary for the welfare of his descendants.

If burial is performed for the benefit of living relations, it only makes sense that those without descendants would receive far less attention in the disposal of their bodies. I have suggested that in the Western/Christian context the primary claim on the bodies of the dead somehow remains the claim made by the dead themselves. Ownership of the body is so important to the Western sense of the self that it extends into the grave—or to the choice for no grave. In the Chinese/Confucian context, however, the primary claim on the body is that of the kinship network, those who have the most to gain or lose by its treatment.

There is an arrogance in individualism, just as there is an arrogance in the transaction that brings Eastern bodies before Western eyes.

In the place where the “Bodies…” specimens come from, to be unclaimed is nearly unimaginable. It is to be removed entirely from the system that, through ritual, leads to the appropriate treatment of the dead. In a sense, to be unclaimed is to lose both the hun and the po, a state that renders the dead, to borrow a term favored by von Hagens, as “former persons.” They were individuals, but they have become mere material. As such, the unclaimed men and women who populate the displays of “Bodies… The Exhibition” may have arrived there, in part, because they fell beyond the protection of the Confucian ethics of the dead.

Although this reading of the Confucian tradition does suggest that it is somehow predisposed to uses of unclaimed bodies that the Western ethical view finds unacceptable, it is a useful reminder that though a rhetoric of rights, equality, and dignity of the dead exists in the West, this rhetoric does not always reflect reality. In the Washington, DC, morgue, for example, there has been in recent years a persistent problem of the overcrowding of unclaimed dead. Until an inspection report announced the problem “significantly reduced” in 2007, the District of Columbia Office of the Medical Examiner had a decade-old reputation of failing to dispose of its dead. At one point there were over one hundred unclaimed bodies crowding a cold storage unit. Bodies were stored on carts, racks, and even the floor in a room occasionally lacking refrigeration, creating a stench so toxic it was judged a health risk to morgue employees. To blame for this apocalyptic scene were the four horseman of paperwork, budget strain, human incompetence, and an inevitable ambivalence felt toward those who die without a living soul to claim them.

The bureaucratic fumbling of a local government may be a far cry from the actual selling of perhaps thousands of unclaimed bodies by Chinese authorities, but nonetheless the point stands that, regardless of ethical assumptions or religious rhetoric, bodies without kin do badly in every corner of the world and in all religious contexts.

It also bears asking if there is something in the Western conception of death—that is, the assumption that there is an element of choice involved in whatever state a corpse should find itself—that makes us particularly disposed to viewing the bodies of others.

There is an arrogance in individualism, just as there is an arrogance in the transaction that brings Eastern bodies before Western eyes. In each there is a sense that the anonymous dead died for our emphatically unanonymous benefit. Although it would be unbearable to most to consider one’s parent or one’s child put on display in this way, the experience is softened by what might be called the “willful assumption of choice”: If it is only acceptable to view a body that has chosen to be viewed, and if I am viewing that body, then it must have chosen to be here.

Regardless of ethical assumptions or religious rhetoric, bodies without kin do badly in every corner of the world and in all religious contexts.

Although it most likely makes no difference to the dead themselves, the concern over how they get where they end up—regardless of whether their final destination is in a display case or a grave—is more properly understood as concern for the living. In this sense, the problem of displaying or not displaying bodies resembles the much older debate surrounding the ethics of organ donation. Because such questions have been asked at least since the first successful kidney transplant in 1954, the discussion there is much more developed. In recent years, a push has been made to establish a global consensus that organs move between humans only as gifts and not articles of trade or commerce. Although that discussion is far too involved to go into here, it is worth noting that even within that global consensus there is disagreement similar to the essential differences between the two types of ethics of the dead we have here called Christian and Confucian: Does an individual own the body, or does the community? Do some individuals have less say in this than others? If an organ is a gift, who can claim the right to make it?

As with organ donation, the ethical concerns surrounding the exhibition of human bodies are as much about how things are as how they might be. Might plasticized corpses become so popular that—like non-Maori sources of Maori heads—people could be killed for the sake of being plasticized, packaged, and shipped around the world?

This is a question that might seem drawn from science fiction. Yet the most pressing ethical question of all comes from a much older text. If the questions raised by this example of “unburied” bodies are as troubling as those faced by Antigone, why is our asking of them far less urgent?

Peter Manseau is the author most recently of the travelogue Rag and Bone and the novel Songs for the Butcher’s Daughter. He lives in Washington, DC.

Author’s Recommendations:

The Undertaking by Thomas Lynch. A poet and an undertaker, Lynch writes simply and beautifully about his family business: caring for the dead and the living left behind.

The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford. The classic exploration of the funeral industry in the United States, Mitford’s book exposes excesses and abuses that have only worsened since it was first published in 1963.

Encyclopedia Anatomica by Monika Von During, et al. Long before the exhibits of Gunther von Hagens caused a stir, the Museo La Specola in Florence, Italy displayed astonishingly lifelike wax models of human bodies in various states of dismemberment. This lavishly illustrated catalog of the museum’s holdings (produced by the art publisher Taschen) approximates the experience of glimpsing under human skin, while raising fewer ethical questions.