If the confident animal, coming toward us,

had a mind like ours,

the change in him would stun us.

~ Rainer Maria Rilke, from Duino Elegy VIII

In his book, The Open: Man and Animal, the Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben makes the claim that Heidegger was the last philosopher to believe that history could still play out the conflict between being human and being animal, and that it was possible for human beings to find their proper historical destiny. But Agamben thinks, since the time of totalitarianisms in the last century, we are living the time of “post history,” the end of history, “a historical telos” where the complete animalization—and forgetting—of the human is in course.

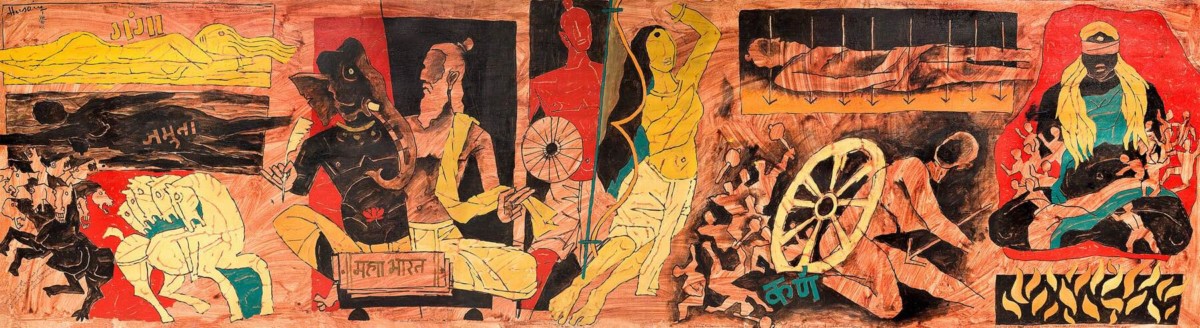

If this is how we may conceive our spectacularly and gruesomely violence-ridden times, what was the time of the Mahabharata? Didn’t the war of Kurukshetra—fought in the name of pompous Kshatriya values, staging the most elaborate valorization of violence and death—also announce the death of its own time, the death of a clan, of a certain “human” narrative? The script of that battle was written by men. Except Shikhandi’s revenge and Draupadi’s curse, the women were not actively a part of the narrative of war, though they suffered the larger discourse of violence. What did the women in the Mahabharata face as they faced a world where love and war was tightly woven around each other?

Nair plays conduit to her lions, the women of the tale, roaring to tell us what those who authored and controlled their lives denied them and how they gave them a raw deal.

Karthika Nair’s Until The Lions (from an African proverb, quoted by Chinua Achebe in an interview, that “until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”) responds to that mighty question with mighty skill as she lets loose her lions upon us. Nair plays conduit to her lions, the women of the tale, roaring to tell us what those who authored and controlled their lives denied them and how they gave them a raw deal. To embark on such a radical task requires great courage and conviction. Nair delves into it with an admirable range of tools in her quiver.

Until The Lions is a “fragment,” one of the earliest techniques in modern lyric poetry that grants a text its open, experimental and provisional character. The “fragment” is often an improvisation of—or in critical conversation with—another con/text. In such cases its task is to illuminate dark or ignored regions. Nair’s book of lyric poems is a collection of voices that announce an altered relation with an epic. She throws up a version, not of the Mahabharata itself but of nineteen voices within it that illuminate the epic with a difficult, often harsher, light. Nair brings alive the voices of mostly marginal women figures (including anonymous ones), two foot soldiers and a dog among others. Nair’s “fragment” comprising of first-person narratives from the epic, makes it especially resonant. It refashions our anthropological relation to the epic, as characters from the past speak to us with a sensibility mediated by the present. Nair’s text moves in a reversible temporality, joining past and present in new, critical ways. We face Nair’s lions breaking out of old narrative cages, to challenge our perceptions.

Future readings of the Mahabharata will surely have to grapple with the new, alternative voice Nair gives to Satyavati, Amba/Shikhandi, Sauvali, Ambika, Hidimbi, Bhanumati, Ulupi and others. Trapped in their own time, playing their characters within the logic of the original text, the voices of these women will challenge their self-narratives through Nair’s version. When Satyavati, wife of King Shantanu and mother of Ved Vyaasa, speaks of the “fully heard but unspoken” casteism and misogyny of vassal lords, when Yuyutsu’s mother, Sauvali, explains the political meaning of rape, Nair provides us with a new arsenal to counter the silences of these characters in the epic.

All fine readings of a text, undertaken against the political interests of hagiography (plain eulogy), finds its critical roots in empathy. Nair’s intense empathy for the women characters in the Mahabharata opens up imaginative doors that both resist the master narrative/s and create its own poetic affirmations. Until The Lions is not simply based on Vyasa’s text alone. Nair has confessedly drawn her sensibilities from both literary and popular sources of the epic that she has grown with: Amar Chitra Katha, Arun Kolatkar, Shivaji Sawant, Pratibha Ray, M.T. Vasudevan Nair, Mahasweta Devi, Bharat Ek Khoj, P.K. Balakrishnan, B.R Chopra’s serial, Iravati Karve, symposiums and dance performances, form Nair’s radically diverse imagination. The epic is part of oral, written and performative history, and Nair discounts the privilege of the original text by allowing all forms of story-telling to influence her narrative.

If a text travels beyond its cultural territory, influences from elsewhere create what we may call, poetic osmosis.

Another innovative aspect of the book is Nair’s use of various poetic forms for each of her characters. She has used the pankti for Dhrupada’s wife, the Malay pantoum for Gandhari, the Persian rub’ai for Ulupi, the glosa for Poorna (Vidura’s nameless mother, named by Nair), rondeau for Uttaraa, canzone for Kunti, triolet for Hidimbi, etc. According to Nair, she chose these forms according to “personality” and “mood.” This polymorphic device allows Nair to create the distinctiveness she sought for each character, as much as create a culturally de-centered context for reading. If a text travels beyond its cultural territory, influences from elsewhere create what we may call, poetic osmosis. When women bound to a particular cultural con/text speak in poetic forms from other cultures, a strangeness of tongue is introduced into their characters which break away from strategies of familiarity working as forms of appropriation.

The most political aspect of this book lies around the question of territoriality and marginality. The war of Kurukshetra is introduced by a “Padavati” or foot soldier. By this move, Nair subverts the glorification of war as the tone of the soldier’s narration is full of irony and sarcasm against the pretentions of valor. The voices of the two foot-soldiers—thefather who introduces the war and the son who draws the curtains—tamper with the moral tone of the war and also expose its class and caste structure. The father, with a tone of doubt and disbelief, mentions how the saints promised equality in heaven or hell for those who die in the war, including “the pariahs… they whose shades taint the land.” He praises the Kaurava heir apparent, Duryodhana, for “thirteen harvests of peace, safety, prosperity” and immediately attaches a false ring to it, when he adds to that harvest, his people who “survive like vermin / on outer rims.” Those who in fear and awe suffer power also know the art of paying false eulogies.

If the hunter, the king, is ‘human’, the women are reduced to beasts with voices alone, speaking in the shadows. Both power and powerlessness (like language and silence) are territorial.

In Nair’s text, the women most palpably verbalize their pleasure and their despair, asserting and reclaiming their wounded subjectivity. They also remap the world by challenging the territorial stranglehold of masculine narratives. The will of lions is caged within the territory demarcated by the hunter, the king. Be it as mothers (Gandhari, Kunti, Ulupi, Uttara, Sauvali), wives (Bhanumati, Vrishali, Hidimbi), or sex-slave (Poorna), women are trapped and mapped within male desire and patriarchal ownership. Naming the unnamable (politics of territory), the women bring out their voices into the daylight of consciousness. They can be assertive, as the dasi Poorna, who conducts her lovemaking with Ved Vyaasa (“Begin with the labia, Lord”), though she ends with the acerbic reminder, “For nothing forever remains, whether thirst or royal norms..” Women’s bodies of memory speak through their tongues like scars. Sauvali, raped by Dhritarashtra, speaks her woe with clarity, “When the king decides to take / you, there is nowhere to run. / The land is his, the rivers are his – the sky / too” And in the same vein, she utters the other part of the same truth in a prose form, “When the king decides to rape me or my kind, no one will use the word ‘rape’. The word does not exist in the king’s world. This body is just another province he owns, from navel to nipple to eyelid, insole to clitoris.” The travails of being captive beasts are laid out in two moves. The king/hunter owns land the way he owns (women’s) bodies: By decreeing his limitless power over the limitations of others, he invents and silences language according to his needs. If the hunter, the king, is ‘human’, the women are reduced to beasts with voices alone, speaking in the shadows. Both power and powerlessness (like language and silence) are territorial.

Satyavati says, “Truth is a beast more wayward than Time.” It encapsulates the first and the last word about the story of devastation. Truth is a beast of power that reduces other human beings to its own animalism. A radical blindness sets upon the world, where violence is freely permitted. It marks the death of time. Until the roaring beasts manage to break out of their cages and bring the other truth (of their condition) to light. Until The Lions marks a liberating moment of our culture.