When Maia Szalavitz began injecting cocaine and heroin in the 1980s, she didn’t know she was at risk for HIV. Media coverage of the epidemic focused mainly on gay men — and it was only by luck that she met someone who taught her how to disinfect her needles before she used them. That was her first experience of harm reduction: a way of addressing drug use that shifts the emphasis away from abstinence and toward reducing risks faced by people who are not ready or able to quit. Szalavitz is convinced it not only saved her from AIDS, but helped move her into recovery.

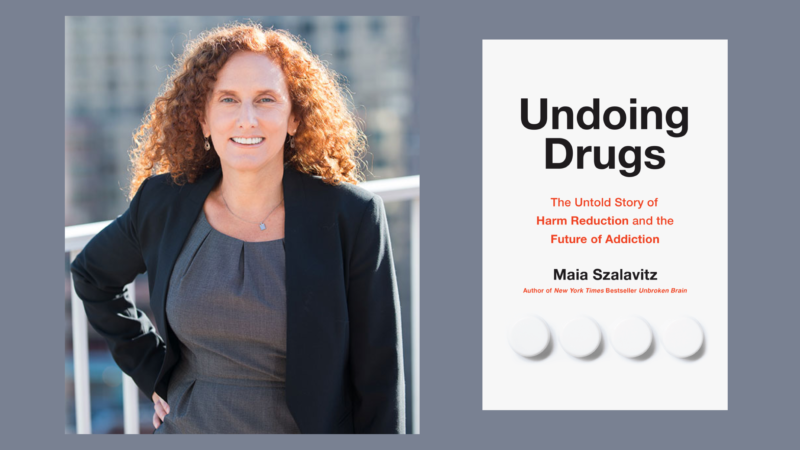

For thirty subsequent years Szalavitz has worked as a journalist writing about neuroscience, addiction, and drug policy. In her 2017 book Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, a New York Times bestseller, she argued that addiction is a developmental disorder. “If you have come to believe that you yourself or an addicted loved one, by nature of having addiction, has a defective or selfish personality,” Szalavitz wrote, “you have been misled.” Drugs alone are not the cause of addiction, she insists. Addiction is also a product of our culture, our genes, and our early traumatic experiences, among other factors.

And that is why harsh policies and programs that enforce drug abstinence — from rehabs that shame and humiliate patients to incarceration, which punishes and stigmatizes predominantly Black and people of color — so often fail. After decades of emphasizing these approaches, addiction rates have only escalated. Ninety thousand people died from overdoses between November 2019 and November 2020, a 30 percent increase over prior years. Overdose deaths now outnumber those from automobile accidents. And the pandemic’s exacerbation of social inequalities — like poor health care, rising unemployment, and homelessness — have drastically heightened the need for a sound and effective approach to addiction.

Szalavitz’s new book, Undoing Drugs: The Unknown Story of Harm Reduction and the Future of Addiction, is the first major history of harm reduction. She begins by considering her own addiction and recovery, and then chronicles the rise of a movement (started by drug users) that has grown since the 1980s, replacing the shame and stigma of drug addiction with effective, life-saving interventions like clean needles and easy access to Naloxone, a treatment for overdose.

Guernica asked Tracie Gardner, a long-time advocate for those with substance use issues, criminal records, and HIV and AIDS, to speak with Szalavitz about this moment in addiction treatment. The two women share a history of drug use, recovery, and advocacy. From 2015 to 2017, Gardner was the assistant secretary of mental hygiene for New York State. Today she is the vice president of policy advocacy at the Legal Action Center.

Their conversation comes on the heels of the passage of the Biden administration’s American Rescue Act, an unprecedented, $30 million embrace of harm reduction policies — which have long been criticized for enabling users, and are now poised to transform the ways we understand and treat addiction.

Tracie Gardner: For those who don’t know, can you explain harm reduction and the harm reduction movement?

Maia Szalavitz: Basically, harm reduction is the idea that policy should be focused on minimizing damage, not stopping people from engaging in any risky behavior. It started with providing clean needles to fight HIV in the 1980s, and it was a movement started by people who use drugs and by former users, along with people in public health.

Needle exchange was started in the Netherlands and later people in the UK took that idea — along with the idea of giving people a safer supply of drugs, including heroin — and brought the broader concept of harm reduction to the US.

Gardner: I’m fascinated by how you narrowed down this vast universe and found the people who helped start the movement and used that to illustrate what you wanted to write about. The chapters are, in some way, standalone stories. But taken together, they bring us to some logical conclusions. So, what was it like finding people who’ve been doing the work — especially the ones who nobody really knew about?

Szalavitz: It was really hard. And I’m sure I’ve missed some of them. But that’s the journalist’s dilemma: oftentimes, the people who really do the work are not the self-promoters. So, finding those folks is difficult.

One of the other biggest challenges was synthesizing the enormous amount of material I had into a cohesive book. I interviewed around 200 people. I don’t know how many books I read, or how many scientific articles, or just random pieces of paper I got from activist groups or the number of people’s files I went through. It was an enormous, enormous organizational task.

But the thing is, I didn’t want to write a thousand-page book. I wanted to write a book that people could read easily, or at least relatively easily, to understand the idea of harm reduction and its history. And that meant using just one or two examples — even though there were like 30 different examples I could have used for everything. I also obviously wanted to make sure that it was representative by race and gender and other demographics. That was on my mind a lot, trying to make sure that I had enough representation from people across the spectrum.

My early drafts were just too much. One of my best friends told me: “You have too many names. Nobody’s going to be able to remember so many names. You have to put them in the footnotes.” I did that, and then it felt terrible, because I imagined the people I wrote about thinking, “Oh, she thinks I’m just a footnote.” But you have to put the reader first. And you have to put the message first.

Gardner: Were you surprised by the ways people’s stories linked together?

Szalavitz: Yeah. It was really interesting and hard to figure out how one person connected with another. For example, apparently, Allan Clear, who helped found the Lower East Side Needle Exchange and became the longest-serving executive director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, first heard about ACT UP’s needle exchange from someone who was speaking at an AA meeting who was in ACT UP.

I also needed to make sure that these stories about harm reduction expressed key ideas in the best possible way. So, some of them were chosen not because they were the best stories, but because they were the clearest stories that occurred in the right place at the right time. This was definitely the most challenging book I’ve written in terms of structure.

Gardner: There are a lot of people I recognize in Undoing Drugs, and some that I didn’t know anything about. But overall, I loved how it pulls things together at the end to say: we’ve got an opportunity for a new direction here.

I thought of the book when I saw the New York Times touting harm reduction on the front page recently. They could have found some Black people to talk to, you know? There was another article about a Black family and overdoses, and it was just despair. There was no sense of: “Are people going to organize?” It was two different takes. One was more like disaster porn. The other one was like, look at these plucky drug users doing things.

I have to say, I did not know a lot about Dan Bigg. I was at the Iowa Harm Reduction Summit when people found out about him passing away in 2018. And it just laid people out like a storm. People were flattened.

Szalavitz: He was really critical to the movement. Probably most importantly, he was the one who started naloxone distribution. Before him, you could only get it in hospitals or ambulances. He was the first to bring this really safe drug — the antidote to opioid overdose — onto the streets where it was needed.

Not only that, but he helped found the National Harm Reduction Coalition, which was the first organization to spread the idea around the US. And then, he brought out the idea that recovery isn’t just abstinence, it can be “any positive change.”

Gardner: I did not know about the “any positive change” slogan. It’s a really interesting integration into harm reduction. Never mind that the idea of “meeting people where they’re at” offends my English major sensibilities. But that’s the slogan I knew from the core of harm reduction — not “any positive change.”

And this issue is still a struggle today as harm reduction and recovery folks try to talk to one another. There’s this whole recovery activist thing where they say, “I’m a person in long term recovery and what I define as long term recovery is…”

Szalavitz: … almost always abstinence.

Gardner: Yeah, and then they’re still really uncomfortable with the idea that someone is even moving toward treatment or abstinence.

Szalavitz: The thing about “any positive change” is that you can be making slow positive changes and still be in a really chaotic state that most people would not label recovery. And I get why people want to count their days so that they can put some distance between that chaos and where they’re at (sorry!) now.

But I think what’s good about “any positive change” and why it remains valuable, despite those caveats, is that if you are engaging in a process of change, the work you’re doing before you get out of the chaos still counts. Also, let’s say you have ten years of abstinence and you slip for one day. In traditional recovery, you go back to square one and those ten years don’t count anymore, and it’s very shameful and discouraging. My answer to that would be: get 90 days again, and you get your ten years back.

So that can kind of be a bridge. If your recovery involves abstinence, it recognizes the value of continuous abstinence but it’s not so punitive. It doesn’t pretend that your earlier successful abstinence didn’t count.

Gardner: I also loved the story of the Needle Eight. I only knew bits and pieces of it, because I was close to one of the defendants, one of the people who risked jail to try to make needle exchange legal in New York. And they won!

Szalavitz: Yes, that was in 1991. Eight people, many of whom were affiliated with ACT UP, were charged with needle possession for attempting to provide drug users with clean needles. A judge acquitted them because the AIDS pandemic, she said, justified their actions. Richard Elovich was a white gay performance artist who was in recovery from addiction and served as one of the attorneys. Daniel Keith Williams was a Black, gay graphic designer. Jon Parker, another person in recovery, was known as the “Johnny Appleseed” of needles. Cynthia Cochrane was a nurse. Kathryn Otter was a trans woman in recovery who is now a politician in Alaska. Gregg Bordowitz was a filmmaker in recovery who was also out about being HIV-positive. And there were two lesbian activists, Debra Levine, a theater director, and Monica Pearl, an author and editor. Their case was a turning point.

Do you think Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow impacted criminal justice policy and helped to move it more toward harm reduction?

Gardner: It helped to explain things that people didn’t understand and didn’t want to look at, and made it kind of inescapable. The New Jim Crow was serendipitous: it came out at just the right time. The fact that it happened to align with the overdose epidemic — and the kinder, gentler approach that was being used — and the way Alexander grounded it in a deep history of how Black people had been punished and criminalized was really useful.

Szalavitz: It would be hard to read her book and not see that this is a racist system. If incarceration was really the best way of dealing with drugs, white people would be locked up as much as Black people are. And they aren’t, which became really obvious when white parents started getting fed up with the drug war during the overdose crisis.

Gardner: And doing this work, we can see how much people internalize the criminalization and stigma. For example, there’s a divide that continues between people who are formerly incarcerated who don’t have drug problems and formerly incarcerated people who do. The “junkies” don’t want to work with the “ex-cons,” or actually, the “ex-cons” don’t want to work with the “junkies.”

So we who are on the “junkie” side are happy to work on justice reform and abolition and all that other stuff, but the “ex-cons” are not happy to work on drug policy.

Szalavitz: You had an interesting experience with that divide when you were in treatment for addiction yourself, at Phoenix House [a national substance use treatment organization].

Gardner: I was there in 2007 with all of these young men who were dealers. They were diverted from doing a prison sentence, but they really weren’t addicted to drugs and did not consider cannabis a drug. So, they would say that they were “addicted to making money.” These young men were in there with their customers. Because the rest of us were just older drug users. These young guys, they smoke weed, but they didn’t do any of the product they were selling. They were going through a “therapeutic” approach to dealing with their addiction to making money. I remember one young man told me, “I decided to do it this time. But next time, it’s just better to jail it, because this is bullshit.”

Szalavitz: They didn’t want therapy.

Gardner: We were doing, like, emotional excavation. They wanted no part of that. They didn’t see themselves as needing it.

Szalavitz: Well, maybe some people in the one percent ought to be in therapy for their addiction to money.

Gardner: That’s the issue, right? Because the harms of being addicted to money for the one percent are not the same as the harms of being “addicted to making money” for these young men. These young men just don’t have enough money to live and for their families to live — that is the problem. It’s not addiction.