Last year, while on vacation in New Mexico, I went on a vision quest with a South American shaman, met the Devil, and came home pregnant. Mother keeps saying, Sins of the father, but I’m trying my best to remain optimistic. I wasn’t even going to tell her about the baby until after he hatched, but then she showed up at my door in her white Chanel coat with that pinched look on her face. You’re pregnant, she said. I could tell by her tone it wasn’t a question. I smiled. Won’t you come in, Mother? and when she didn’t, I said, Suit yourself, but it’s a lot colder out there in the hallway, and retreated back into the apartment. I don’t understand how this happened, she said. Do you need me to explain the mechanics to you? Don’t be crass, Fiona. I saw you two weeks ago, thin as a cane, and now, well, I’m sorry dear, but you’re enormous. In defense, I placed a hand on my belly, on the hard shell forming beneath the skin. I pictured the armored back of a tortoise; I whispered its secret name, Lizard-Baby.

Mother removed her winter gloves and placed them on the island counter and began to unbutton her coat. I suppose you’ll be wanting me to explain this to your father. Don’t worry about Daddy; he’ll be fine, I said as I shouldered out of my bathrobe and dropped it on the kitchen floor. My God, Fiona, what are you doing? Mother asked. Oh, don’t be so prudish, Mother. It’s just the body, I said as I stretched out on the large slab of slate rock I had purchased from the garden store the day I returned home from New Mexico. I’d positioned it in the center of the living room where the coffee table once stood, having pushed all the furniture against the wall. I never understood the attraction of sunbathing, not until I was pregnant, that is. There was something delicious, luxurious, erotic almost about the feeling of the smooth hard surface against my bare skin, warmed by the heat lamps I’d angled around it. Mother retired to the lazy chair. Your sister never would have done this to our family, she said. I closed my eyes. Well, I’m sorry to have disappointed you.

Tomás was equally dissatisfied by the turn of events. If I’m being completely honest, I hadn’t given much thought to how he’d figure in all this, not until a few days later when he rushed into the apartment. I forgot I had given him a key. I was lying down in the living room under the lamps, reading a magazine. It’s not mine, is it? he asked, aghast, I’m sure, at the sudden curvature of my stomach, at the trail of dark hair and sweat that graced the incline down from my navel. No, Tomás, it is not yours, I said, and saw the breath escape him. For a moment he looked relieved. Wait, what do you mean it’s not mine? I mean it’s not yours, Tomás. Well, if it’s not mine, then whose is it? he asked. I turned over on my side. You wouldn’t believe me if I told you. Why are you even here? Your mother called and reamed me out for knocking you up. Mother. Well, I’m sorry, but she was mistaken. Is there anything else? No, I guess not, he said, and then, Can I get you anything? No, I said, and smiled, but it’s sweet of you to ask. I guess I’ll just be going then. I think that’d be for the best. Tomás looked down at his feet. His black curls covered his eyes as he tended to a mark on the floor with the toe of his shoe. You’re sure it isn’t mine? he asked.

The following Monday, I went into the office to file for maternity leave. It always seemed strange to me that, for all intents and purposes, maternity leave and disability are practically the same thing. Though perhaps not so strange, I considered as I waited in the lobby, opting for the elevator instead of the stairs. I was still trying to negotiate the change in my weight. My boss was, for obvious reasons, surprised by the state I arrived in, but gracious still. When are you due? he asked. I told him I had no idea. Soon, I hope! Well, take as much time as you need, he said, patting me awkwardly on the arm in that way men have of handling anything remotely hormonal. Margaret, the woman who worked in the cubicle next to mine, congratulated me on my way out. I noticed you’d been wearing looser-fitting clothing recently, you sly fox, you, she said. A baby is one of God’s greatest gifts. I decided to play it coy. Well, it’s certainly a gift from somebody! I said.

I always thought it was such a cliché when women described giving birth as pushing something the size of a watermelon out of a hole the size of your fist. First of all, I don’t know about you, but the hole in my pink panther is not the size of a fist, and second, have you ever seen a baby? Not the size of a watermelon. Besides, babies are squishy. You know what isn’t squishy? An egg.

Three weeks home from New Mexico, I gave birth to the egg in my bed, in the apartment, in the middle of the night. Earlier that evening, I got an inkling it wanted out of my body. I could not sit still. I just kept circling the island counter—round and round and round I went. I considered driving myself to the hospital, but what could they do? I asked myself. Around eight, I began piling every soft thing I owned onto the bed: washcloths and beach towels and the cushions from my couch. I shredded rolls of toilet paper with my fingernails and crumpled up the Sunday paper’s holiday ads, sheets upon sheets of wrapping paper. I reached out to an old friend, a girl I knew from undergrad, who’d gone on to study veterinary medicine at Cornell. Relax, she assured me over the phone, you’re just nesting. When there was nothing left, I burrowed deep down in the bed and waited, and when it came time to push, I felt as though my body was being split open. I reached down and felt the tip of the egg peeking out from the space between my legs. Then, when I was able to get a good grip on it, I pulled that sucker out with a sudden pop. My hips disjointed and buckled back into place. I had never in my life felt more alone or more powerful.

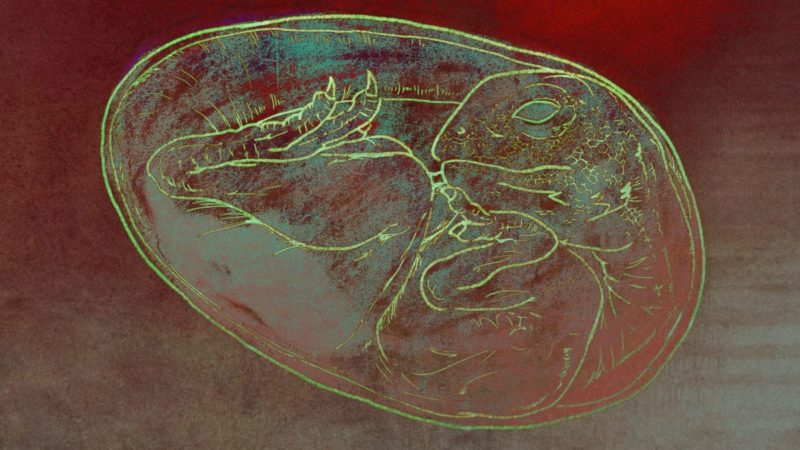

As difficult as the birthing was—I could barely walk the following few weeks—the month and a half, forty-two days to be exact, that came after were the hardest because of the waiting. With a normal child, the birth is the climax, the grand payoff for months of preparing. Not so with a lizard-baby. I relocated the nest to the slate slab and spent my days adjusting the temperature of the heat lamps, caressing this hard speckled thing that was of me but no longer a part of me. I lost weight. You have to eat something, Mother told me. If only I knew he was all right in there, I said, stroking the egg. She called Tomás, still convinced he was responsible for the mess I found myself in, and one night he showed up at the apartment, this time troubling himself to knock before entering. I slumped to the door. I don’t have the energy to go through this with you tonight, Tomás, I said. He grinned and held up a high-powered flashlight. I come bearing gifts. Trust me, he said. We went to the nest and turned off the heat lamps. The apartment was entirely dark. I did some research, Tomás said, flicking the lantern’s switch and shining the light through the backside of the shell. It’s called candling. And there he was, my son, floating in the fluid membrane of the egg, flexing his five fingers as if to reach out and touch me.

When the lizard-baby hatched, it was like the best Christmas ever, though by then Christmas had long come and gone. The whole family was there—Mother and Daddy and my sister, Becca. Tomás was there too. We stood in a circle around the nest in the living room as the lizard-baby struggled to extract himself from the crumbling walls of the egg, nuzzling his way out with the flat of his nose. Daddy reached out to peel back a piece of the shell in order to assist him, but Mother swatted his hand away, saying, Don’t you rush him, Charles. He was born to do this. Does no one else think this is bizarre? Becca asked. Oh, shush now, Rebecca, Mother said. This is an important moment for our family, and I won’t have you spoiling it. Already, I could see that things were changing—my ascension in the family ranks. I could tell by the expression on my sister’s face that she saw it too. Becca, the favorite, was being usurped.

To say people were eager to meet this miracle child of mine would be an understatement. The most adamant, I found, were the girls from the office. I’d been gone from work for almost eight weeks, and though my paid leave had run out, I told them I had no intention of returning. As if that matters, Margaret told me. A baby is a baby and we want to celebrate. We’re coming. So, true to her nature, Mother hosted a shower at the apartment. More of a luncheon, she assured me. Just a few of your coworkers, Rebecca, and myself. Nothing fancy. Finger sandwiches and iced tea. I don’t know how we’ll convince your father to stay at home, though, he’s so fond of the baby.

At the shower, the women from work couldn’t get enough of the lizard-baby. They fawned over his skin, scaled and pale green, the way he periodically ran his tongue over his protruding black eyes to compensate for his inability to blink. Yup, my father said, look at those eyes. He definitely gets his eyes from my side of the family. And then he lowered his voice, His tongue though? One hundred percent your mother’s genes. Charlie! Mother said from the kitchen, but anyone could see she was blushing. Though I’m sure they all wanted to, Margaret was the only of my coworkers I trusted enough to hold the lizard-baby, but as she cradled him, he pawed at her shoulder and the setae on his toe pads snagged on the fabric of her cable-knit sweater. I’m so sorry, I said. We’ll replace it, I promise. Oh, please, she said. If you mind a mess, don’t hold a baby. That’s what I always say. The girls remarked on how well-behaved the lizard-baby was. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a newborn smile as much as he does, one said. Yes, he’s a happy baby, I agreed. Becca peered over Margaret’s shoulder. I think that’s just how his face is, she said. That’s because he’s always happy, Rebecca, Mother informed her. Becca was just sore because the week before, she had tried to scratch the lizard-baby under his chin and he bit her finger. Daddy snapped, He isn’t a dog, Rebecca! as Mother whisked the lizard-baby out of the room.

There are quite a few upsides to raising a lizard-baby, despite what you might think. I’ll hip you to one—it’s a lot less expensive than caring for a normal baby. I mean, have you been to the baby aisle of a department store lately? Nothing is cheap. But with Daddy’s admonishment of Becca in mind, I soon realized we could get everything we needed for a fraction of the cost at a commercial pet store. Take the crib, for example. An average crib can go for anywhere between $200 and $800, but I got a Petyard Pen Plus for $129.50 and erected it around the slate slab right in the living room. It even folds up, so I can take it to my parents’ or Becca’s if I want to. Also, doggie diapers. They’re less expensive than Pampers and there’s a hole for the tail. I even found myself eyeing those little garments, the kind that slip over the head of your pet and fasten around the waist. For Easter services, Mother brought over a little Jackie O coat. It was only sixteen dollars, she said. I couldn’t help myself.

We spent the Fourth of July with my family at my parents’ place up on Seneca Lake. Daddy set up the pen in my old room, but the lizard-baby spent most of the day on the couch with Becca. He’d finally started to warm up to her, due in part, I’m sure, to the fact that she’d taken to stashing dried mealworms in her pants pocket. She portioned them out one by one until the lizard-baby settled down on her lap. Sitting there, the look on her face was triumphant. Just try not to spoil his dinner, I told her. She responded by flipping me the bird. Rebecca! After dinner, we congregated out on the lawn for the fireworks display, but when the first one exploded, blossoming in the sky with a flash of light and a sonic boom that filled the air, the lizard-baby let out a sound I’d never heard from him before, a combination of his lovely chirping and the awful squawk woodpeckers make. The fireworks literally scared the piss out of him—I was wet all down the front of my shirt—and it took us hours to coax him out from under the deck.

All things considered, I thought I was handling the whole situation with about as much grace as could have reasonably been expected of me. Even when Mother stepped on the lizard-baby’s tail and the damn thing fell off. Even when some punk at the grocery store turned to me in the check-out line and exclaimed, quite loudly, Dude, your baby’s a lizard! I took it all in stride. Still, nothing prepared me for the shedding. When I think of shedding, I think of Lassie. Or snakes. I think of Adam and Eve. I do not think of children. Imagine, your six-month-old flaky and chaffing over the entirety of his body. You dowse him in baby powder until dusty white clouds trail behind him; you rub baby oil into the scales of his cool green skin until he glides across the floor like a Slip ’N Slide, gleefully chirping. Still, at day’s end, when you put him to bed, he crinkles in your arms like packaging paper. Now imagine one day he slips from that skin as though from a wetsuit.

It was September, the humidity of summer had recently lifted, and I hadn’t left the apartment all week. At that time, I was still waking up every few hours to feed the lizard-baby the small pink mice I kept in the freezer, or to deal with his dry skin, or to rock him to sleep, and by Friday, I’d hit a wall. I was making dinner and the lizard-baby was in his crib, playing with the makeshift rattle Daddy had dropped off earlier that evening—a brown paper bag filled with a handful of crickets, sealed, and fastened to the end of a popsicle stick. When he shook it, the crickets popped against the bag, trying to escape their paper prison. Pop, pop. Pop, pop. I was straining the spaghetti when I heard a strange kind of crunching. I just assumed that, impatient and hungry, the lizard-baby had torn into the paper bag of the rattle, but when I looked up from the sink I saw that it lay beside him, untouched on the slate rock, and my son was standing behind a perfect, opaque cast of his little lizard body, the head of which he’d begun to eat. I couldn’t help it; I screamed and dropped the spaghetti. Startled, the lizard-baby snatched the skin-sheath up in his mouth and greedily devoured the thing before I could reach him to confiscate it. I called Tomás, and when he finally showed up at the apartment, I thrust the baby upon him. I haven’t showered in three days, I haven’t slept in weeks, I’ve given birth to the Devil’s son, and now’s he eating—I can’t—I just can’t, I said. I’ve ruined my life! Then I went to my room, closed the door, and fell asleep crying.

It’s a conversation I don’t think we have often enough. Or maybe we do, and before I got pregnant, I just wasn’t paying attention. But I don’t even think that’s true, really. Even now, when I hear other parents talk about the difficulties involved in raising a child, how it forces you to completely reconfigure the terms of your life, it’s a side comment, a passing remark that’s casually dismissed in the face of all the joy that accompanies new parenthood. I can’t say for certain, but I’m pretty sure I’ve never heard a single parent make this assertion in quite the same way. Raising children is exhausting, and no matter how profound my love for the lizard-baby was, there were days when I woke up already feeling defeated as a human being. I slept clean through the night, and when I got up the next morning, I launched out of bed in a state of panic. How long had I slept? Where was my lizard-baby? I opened the bedroom door full of dread, but there was Tomás, calm as could be, in the living room, crouched over a small cube-shaped machine. He’d wrapped the lizard-baby up in a peanut-shell sling tied around his chest, and from it, the lizard-baby reached up with his little ribbed fingers, tugging at Tomás’s lower lip. He chirped and smiled when he saw me. Everything’s fine, Tomás said, flipping a switch on the machine, which began to emit a stream of fine mist. We just need to humidify the apartment.

The lizard-baby grew at a reptilian rate. By October he was the size of a toddler and in complete control of his faculties. Even his tail had grown back by then, though it was fatter than before and a kind of cold gray color. I’ll never forgive myself, Mother said, shaking her head. I’ve scarred him for life. But the lizard-baby didn’t seem to pay much attention to this transfiguration of his body. At the end of the month, the entire family agreed, we’d take him trick-or-treating on Halloween. What are we going to dress him up as? Becca asked. Mother scoffed and Tomás laughed. Seriously? he said. It’s the one night out of the year when nobody’ll look at him sideways. I, myself, wasn’t so sure, but Tomás was right, the lizard-baby just passed as a particularly well-disguised child. Parents stopped us to applaud our work right there on the street. You must be in television, one woman said. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more a realistic costume. Everything was fine, better than fine, until we stopped at a house where some guy insisted on getting a photograph of his kid, a Ninja Turtle, Donatello, I think, with the lizard-baby. I love those commercials, he said, pushing his boy shoulder-to-shoulder with mine, who was distractedly shaking the candy in his hollow plastic pumpkin, the sound no doubt reminding him of the rattle waiting at home. Just before the man snapped the picture, I remember thinking about the fireworks on the Fourth of July. The flash went off and the lizard-baby shrieked like a rabbit. The plastic pumpkin crashed to the ground, sending chocolate bars flying, and my son dropped to all fours and scampered off into the night, the neighborhood crowded with innumerable beasts.

He’s a big lizard! I said, frantically trying to describe my son to one of the officers who’d shown up at the scene. All I could think about were those pet alligators that people abandon to grow up in the sewers. Yes, I understand, Miss, but what does your son look like when he’s not in costume? the officer asked. Don’t forget about his tail! Becca added. Yes! Mother said. It’s big and gray and ugly. No! Not ugly! It’s beautiful! My grandson is beautiful. Dear God, this all my fault! The patrolling officers fanned out and canvased the neighborhood. Do you have any idea where your son might have gone? No, Tomás said. He’s never been out this way before.

An hour after he went missing, a woman, the one who’d made the comment about me being in TV, showed up with the lizard-baby. He was holding the hand of her young daughter. I can’t thank you enough, I said, clutching the lizard-baby to my breast. Charlie, where’s my pocketbook? Mother shouted to Daddy. We’re writing this woman a check. Please, the woman said, picking up her own child, a towheaded girl dressed as Kermit the Frog. We parents are all in this thing together. It’s not easy being green, I know.

The next morning, Tomás came by the apartment with a suitcase and a cardboard box of his stuff. What are you doing? I asked when I opened the door. You can’t do this by yourself anymore, he said. He needs a father. He has a father, I reminded him. That may be so, he said as he brushed past me, but he still needs a dad. And that was that.

In the end, I decided to return to work the week after Thanksgiving, almost a year to the day since I took my trip to New Mexico and everything changed. Tomás sleeps in the spare room, but most nights I come home and find him lying down in the baby’s pen, the lizard-baby curled up against his chest, soaking in the heat from his body. I stand there watching them like that, on the verge of a compelling happiness, and then I think, Where are we going to enroll him when the time comes for his schooling? Will the other children taunt him the way children do? How will he play sports or drive a car comfortably with that big tail of his? What girl will want to kiss a lizard-boy on the night of her prom? I tell myself I could navigate these things on my own, without Tomás’s help, without the assistance of my family, but I’m grateful I don’t have to, and when you get down to it, that’s a good thing, I believe.