Were you in combat? In the presence of people in military uniforms, I sense this question hunching behind the slightly wider berth we give them as they board the plane ahead of us, and behind the socially appropriate “Thank you for your service.” Were you in combat skulks in a jumpy little cluster with other questions: What’s it like? Did you kill anyone? Did you see anyone die?

Aaron Hughes, who served in the National Guard in Kuwait and Iraq, shared his version of war stories in a performance called “Tea” which he performed more than fifty times, both nationally and internationally. Last Veteran’s Day, he performed at the Museum of Modern Art. When I saw it in 2009, I expected something like a press conference. But when the audience arrived, Hughes invited us to sit on an oriental rug in a circle, then handed out cups of strong sweet tea, explaining that this was the custom in Iraq. For most in the US, the story of these places began with the war, we have no awareness of a norm to disrupt. Years before the drawdown began, research on the coverage of the Iraq War found that the “daily life” in Iraq almost entirely absent from reporting, despite the presence of embedded reporters. Daily life is the warp through which we weave meaning into our days and weeks, whether this includes coffee with our commute or tea on our carpet.

At the beginning of Hughes’ performance, the group’s interactions were tentative and polite in the middle of awkward silences. When the tea was served, Hughes shifted from a reticent, casual attitude to a more theatrical one. He is unusually tall, with long arms, large hands, and a wide, boyish face, making his deliberate gestures, which he moved into slowly and held, striking. He began by asking each of us to remember what they did when the war began. People tended to share a vivid memory (“I can remember where I was”) and an emotion, and most agreed that after that moment, even if they took part in a protest, their lives returned to the way they were before. Audience members were generally surprised to realize how much time had passed. Framing their own in lives in the timespan of occupation, some spoke about college, others about traveling abroad, some spoke of jobs, divorces or marriages.

Without friends and family in the military, without familiarity, stereotypes breed: soldiers become to some degree walking examples of national myths.

Less than half of one percent of the US population is in active military service, and fewer than this number have or will serve on active duty in Iraq or Afghanistan. So if we want the kind of understanding of another’s experience that comes from talking to a person that served in Iraq or Afghanistan, most of us would have to hear it from a stranger. Without friends and family in the military, without familiarity, stereotypes breed: soldiers become to some degree walking examples of national myths.

Unlike the economy, against which we can each measure ourselves—our debt, savings, employment status, plans, aspirations—we tend not to relate the state of our own lives to the state of the wars. And while you probably know someone who was affected in some way by the mortgage crisis or has a stake in a higher minimum wage, it is statistically unlikely that you know someone who served in Iraq or Afghanistan. Eric Malmstrom, a member of the National Guard who served four years in Afghanistan, contrasted his parents’ sense of Vietnam and grandparents sense of World War II as “defining events” of their lives with the “negligible effect” of current wars on his own friends and family.

When soldiers are invited to appear in public—in op-eds and interviews— they are most often asked about their suffering and hardships in conflict areas, the suffering they’ve witnessed. Army Captain Matt Mabe, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan between 2003 and 2010, returned to the US and civilian life to find himself surrounded by colleagues who stereotype soldiers as both heroic and ignorant, “lost, disadvantaged, exploited.” Rather than speaking from their particular skills and job experience, members of the military are handed the microphone to demonstrate emotional and psychological impact—of war, of the failings of Veterans’ Affairs. In order to more fully include their insights in public discourse, we’d have to begin to credit them more as professionals, less as figures of heroism and martyrdom.

When film and television shows take a dark look at the moral compromises of war, as all “serious” ones do, the person at the center is hyper-competent and wields a large measure of control in his or her scenes: “Homeland,” “The Hurt Locker,” and “American Sniper.” This is the flip side of the “lost and disadvantaged” stereotype. How to portray the work aspect, the management and mundanity, of over a decade of war? The expertise of personal experience is sometimes tied to political judgment. Linda Tirado’s description of the sorts of decisions poverty forced her to make speaks directly to the debate about social welfare policy; her blog and article in The Huffington Post, put her forward as a kind of expert. Pairing his professional experience as a doctor with his talent as a writer, Atul Gawande exerts significant influence over the discourse on long-term care and dying. People who speak from this vantage point do get handed a mic on the stage of national discourse from time to time. In 1922, media theorist Walter Lippman expressed confidence that though media representations of distant places and people were distributed on a mass scale, they would not become monolithic and static; through their function as intermediaries in the deliberation of many different peoples, they would be “subject to check and comparison and argument.” But in the case of war, the miniscule numbers of us who serve, and the way these people are positioned and characterized, prevents an important check and comparison.

There is an intensity and narrowness to my curiosity about soldiers: to me it seems to spring both from political guilt (they served and I didn’t), and existential wonder (they may have been in the middle of death of violence to a degree that I never will). But this quality of intense and narrow focus cuts across several strata of our lives. The American public imagination is well-stocked with scenes of the last twelve years of war: “American Sniper,” “The Hurt Locker,” “Homeland.” In the Reddit space of prior consent and anonymity, thousands commented on the thread “What aspects of war/combat does Hollywood fail to portray?” Several commenters pointed to the first twenty minutes of “Saving Private Ryan,” and Spielberg’s recording of actual bullets fired in close proximity to the cameras. One commenter said he heard of a veteran would couldn’t sleep for weeks after watching that scene.

Before the drawdown, in 2011, Pew reported that 1 percent of news coverage was devoted to the war in Iraq; of the war in Afghanistan it was 4 percent.

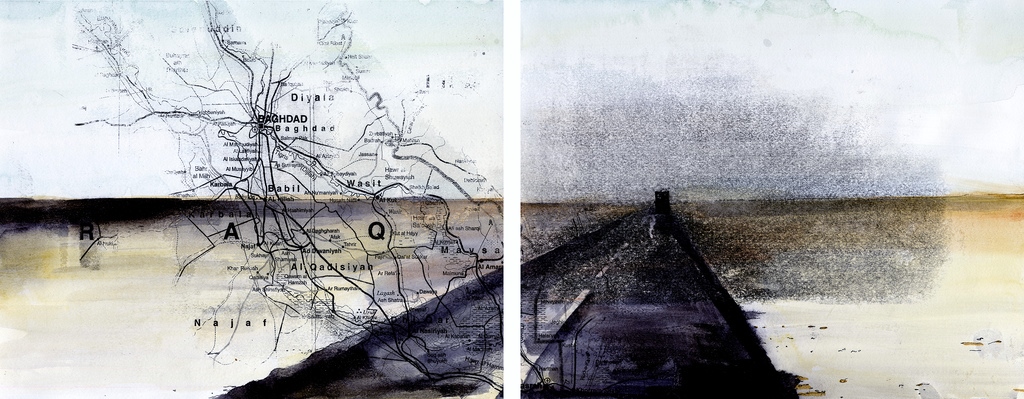

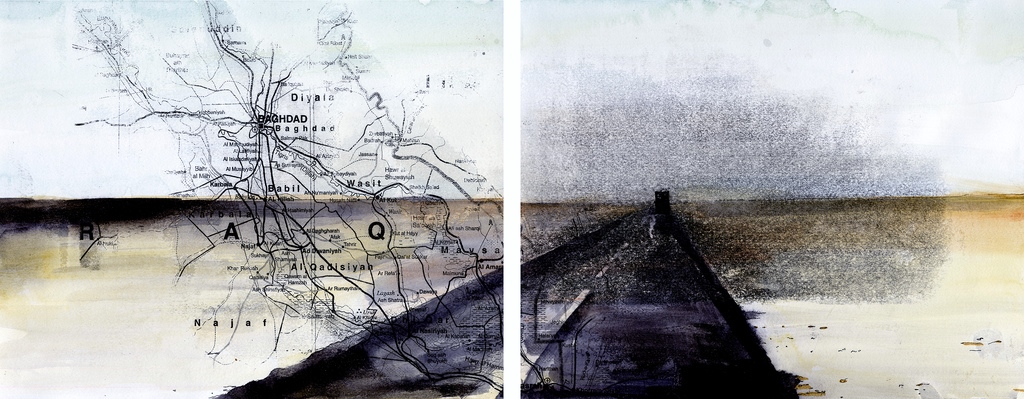

In 2007, the news of the Iraq war consisted of “crisis and crime,” according to a study by the Pew Center for Journalism, focusing on flash events much more than longer arc aspects of the occupancy—the way strategies play out, their revisions, their impact on the country. This is in the context of a war that received scant coverage in newspapers, according to the Neiman Center, and even less on television. Before the drawdown, in 2011, Pew reported that 1 percent of news coverage was devoted to the war in Iraq; of the war in Afghanistan it was 4 percent. High level officials, politicians, and pundits speak of military strategy and goals, framing coverage of violent events.

For all the repetition, the spectacle, the grit, the way we shove our faces in what is supposedly one of the hardest realities—violence and death—we’re missing something. What is missing of course is the dailyness of it all, something we might get closer to if we were more familiar with the reality of soldiering as a job, of soldiers as people with a range of professions that provide critical insight on military policy, protocol, and their realities in practice. For those of us who didn’t serve, rather than forcing ourselves to confront the reality of war, the tension, drama, and spectacle of war in movies and television might be a kind of evasion. The same can be said of the pattern of filling up that small percentage of news coverage of the war with brief reports on violent events. A 2007 study of US coverage of the Iraq war claims that through the repetitive reporting of violent events we are “numbing ourselves to death.” Journalist Sarah Stillman focused on the issue of labor rights in Iraq and Afghanistan. Asked why this aspect of the wars was underreported, she said, “It’s hard enough to get readers to be willing to engage the issues facing US troops; perhaps it’s war fatigue?” And then there is the other side of drama, the mundane: “War is 99 percent boredom and 1 percent sheer terror,” said one Redditor. “Show them how boring it is,” said a Vietnam soldier to the man with the camera in a 1970 documentary “The Quiet Mutiny.”

Along with post-traumatic stress disorder, one of the accepted reasons for why veterans are marginalized when they return from war is that their experience is not only different from others, but also that their experiences are incommunicable. Walter Benjamin made this argument about World War I, decades later the anthropological and psychological study, The Vietnam Veteran Redefined, made the same argument. This recognition that the experience of violence and proximity to death is somehow beyond our capacity to express to each other may explain the great technological effort and artistry that continually goes into cinematic depictions of combat. But touching lives, knitting together a fuller understanding of the consequence and character of these wars, is not a question of depicting combat in a way that “gets it right,” instead it is a way of talking and listening to each other.

Hughes’ last story contains both suspense and violence. His fellow Army National Guard soldiers, and Marines in a truck convoy. The territory they were covering was sketchy, and Hughes described a back-and-forth between the Marines and the National Guard over who should lead the convoy and go first. The argument ended with it being determined that Hughes’s National Guard unit would follow because they only had one truck with any means of communication, and besides as Hughes says, “They’re the Marines.” During the convoy, Marines’ truck in the convoy hit an IED; and the Marines had no way to alert the National Guard soldiers behind them. And the National Guard, without proper communication, had no way to call for help. At this point, Hughes’s narration turned away from the violent event and its consequences. He said he remembered that while they waited for the medics, they all sat around, smoked, told jokes, and someone took a shit in the middle of the road. After the medics had come and gone and the convoy got on the road again he remembers passing the location of the IED attack and looking down and seeing blood and medical supplies covering the road.

“Arriving home and changing out of my uniform, I rejoin the vast majority of the population who go about their lives untouched.”

War stories carry the expectation of a certain emotional as well as narrative arc. By withholding the violent crisis, the crux, and a denouement, Hughes did not allow the audience to leave the story with the sense that the evening’s entertainment was complete. He also forestalled the strong urge to fill silence with condolence, which would have allowed us to take leave of each other in a more socially graceful way. We were not granted this fictional or social frame of an end, an exit, and instead were forced to literally sit with an awareness of a gap between our responsibility, to Hughes socially in this moment, as well as to our place in the war, and our daily lives as we live them. “At the conclusion of my training, I leave behind this tiny minority of Americans who bear the burden of these two conflicts,” Malmstrom wrote. “Arriving home and changing out of my uniform, I rejoin the vast majority of the population who go about their lives untouched.”

In response to a 2014 survey, 70 percent of active members of the military said they did not support “sending a substantial number of combat troops to support the Iraqi security forces.” In 2015, a survey of the general US population found that a majority of the general population support “sending troops back to Iraq” by a margin of 2 to 1. Those who enlisted have a kind of patriotic altruism (90 percent say they are motivated by a desire to serve their country) and, we can reasonably assume, that they enlist with a sense that military intervention can change things for the better. So in terms of the distance traveled in political view, active duty military personnel have lapped those liberals who tend to think of themselves as noninterventionists with the exception of humanitarian crises.

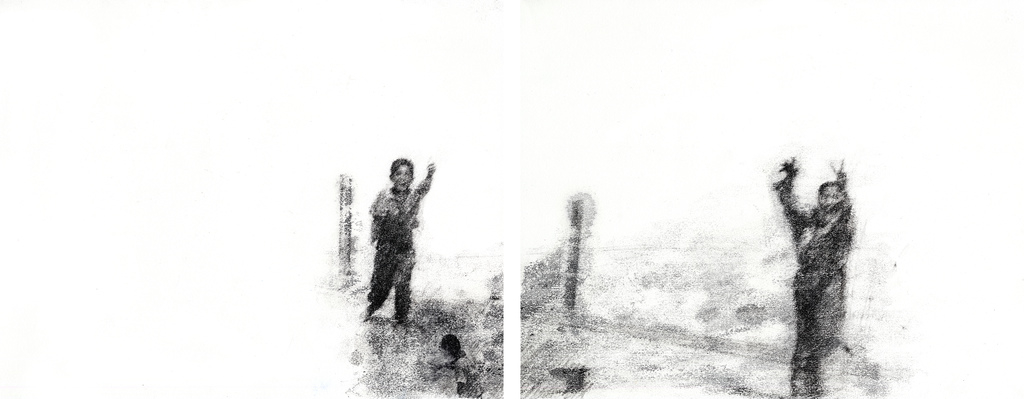

Before he joined, Hughes spoke with a recruiter about how the Illinois National Guard had sandbagged the Mississippi River to protect towns from flooding. Perhaps partly because a tornado had gone through the small town of Golden, Illinois where Hughes lived, this work of the National Guard caught his eye. But he did not find himself protecting and helping in this way once he was deployed. He describes the way that memories of children running up to supply trucks to ask for water haunt him. “What we’re performing over there, our roles over there, the performance of our roles never fits,” said Hughes. He added “occupations don’t build democracies.”

Asked about daily life when he was deployed, Hughes said, “On missions I often felt like it was a constant monotonous anxiety-filled boredom. Staying awake while driving hour after hour in the bright light and heat of the desert. The only sound you could hear was the roaring motor and howling wind. It was exhausting and just as I would start to fall asleep at the wheel I would remember “stay alert stay alive.” And I would begin scanning the road for IEDs. Same can be said of hours and hours of guard duty. Monotonous.”

Kevin Basl, a member of Iraq Veterans Against the War, spoke to me of the kind of workplace futility that I associate with dreary office jobs, not soldiering in a war zone. Trained and deployed to serve as a radar monitor, he said, “The radar remained inoperable for much of the deployment. My team had to wait for private contractors to come make repairs, which could take weeks. In some cases, we were actually training the contractors on how to do our job.” Routines in combat zones can be much like routines anywhere. Basl described his days and weeks as consisting of a round of tasks, meals, free time—all taking place within a small amount of space. He filled generators with fuel, tended the radar, exercised, made music when he could. “Sometimes the radar wasn’t spinning for whatever reason—overheating, too dusty, crappy parts. I’m not exactly sure how the information we were sending up to the operations center was used. They hardly ever noticed when it was nonoperational.” When he passed a line of zip-tied men in the course of his work, when a mortar exploded a dumpster outside the radar room where he sat, he was reminded that he was in a war zone.

On a Reddit thread this year, one commenter responded to the question” “Soldiers of Reddit who fought in Afghanistan, preconceptions turned out to be wrong?” with a story about how much damage his unit brought to people living in the Tanqi village. People turned out to help when their vehicles were stuck in the mud, he said, then left at night because they knew this event would draw fire and their homes would be attacked at night. News coverage of Vietnam did, at least at times, capture the work culture and management of that war on an intimate level. See Morley Safer narrate the series of decisions that led to the burning of the village of Can Ne in 1965. This was not one of the events that was shocking in its spectacular brutality, but in its mundane mismanagement. See how John Pilger’s interviews with soldiers in Vietnam grants them authority to give their views about the orders they have to follow in “The Quiet Mutiny.” Our “support the troops” culture does not stigmatize veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as we did those of Vietnam. Yet while our general approach to those troops is more embracing in the abstract, we lock out difficult realities that they carry.

Hughes prefaced one of his stories with a question: “Do you want to hear some trivia?” Once the audience answered yes, he talked about a woman who approached him on a bus and asked him if he wanted to hear some trivia. She asked if he knew of a park outside Chicago. He did. She told him there was building inside the park that used to hold German war prisoners. Hughes was skeptical, but she said she used to play in the park, and she remembered going there with her friend to blow kisses to the “beautiful blond soldiers.” Hughes, tall and beautiful himself, asked the audience why the woman would tell him this story: “Did I remind her of a German prisoner of war?” The audience around me was silent and awkward, some confused and sad at the thought that this person who had been so thoughtful with us, so morally searching, would be compared to a Nazi soldier. Other audience members were clearly waiting for their chance to ask the question they took with them to the performance—“How did you go from being the kind of person who would enlist to being an activist?” “How many women were in your unit?” Hughes held an awkward silence, then asked, “Do I remind you of a German prisoner of war?”

What is it to be a prisoner of war? One could see imprisonment as being confined to the kind of silence that makes you simultaneously present and invisible to those around you, to have something to say that no one can or will hear. When I interviewed Hughes, I asked him why he began this story by asking the audience if we wanted to hear some trivia. He answered that he was trying to point out “the level at which we process this information, it’s all trivia.” Trivia are just details, not significant enough to shape the basic understanding of a phenomenon such as war. I see in Hughes’ performance, as well as the work of other members of IVAW, careful strategies for shifting the ground on which we process war narratives.

“Watching a friend die isn’t ‘devastating,’ ‘traumatic’ or ‘terrifying.’ It just is.”

Kevin Basl is an instructor for Warrior Writers and Combat Paper NJ, two arts-focused workshops for veterans. Flipping through a portfolio of Combat Paper artwork at a public workshop at Interference Archive, he told me the story behind one piece in particular, “Why I Don’t Write War Stories” by Justin Jacobs. When Jacobs attended a Combat Paper workshop, he was just a few years out of the Army, trying to “blend back in, but he had all this unresolved stuff,” a common experience for veterans, as Basl described it. Inspired by the workshop, Justin wrote a sort of open letter to his peers and turned it into visual art—images of trees and a helicopter surround his words. Jacobs created the paper on which this letter is written out of an old military uniform. On this handmade paper, he wrote: “I’m not upset that my peers don’t understand the stories I try to tell them. In fact I’d be mad if they thought that they did. Watching a friend die isn’t ‘devastating,’ ‘traumatic’ or ‘terrifying.’ It just is. That’s the feeling and it’s one that doesn’t have a name. I haven’t figured out how to write that down and this is why I don’t tell war stories.”