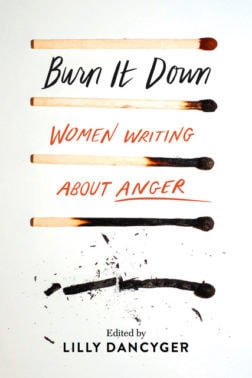

“Every woman I know is angry,” Lilly Dancyger writes in the introduction to her incendiary new anthology Burn It Down: Women Writing About Anger. In its pages, twenty-two of those women examine where anger lives in their bodies, and how it surfaces in their thoughts, words, and actions: the ways it shrinks them, and the ways it makes them bigger.

Dancyger, an essayist and outspoken feminist, was surprised by how tamely many of the writers approached the subject of anger in their early drafts; she found herself encouraging them to get the full truth of their experiences on the page. With that, the floodgates of repression burst open and the stories thundered forth.

Dancyger, an essayist and outspoken feminist, was surprised by how tamely many of the writers approached the subject of anger in their early drafts; she found herself encouraging them to get the full truth of their experiences on the page. With that, the floodgates of repression burst open and the stories thundered forth.

Take Rumpus editor-in-chief Marisa Siegal. After years of suppressing rage at her drug-addicted father, he locked her out of the house, prompting Siegal to smash through the window. “There was something beautiful about the glass exploding into diamonds,” she writes. “I think, maybe, the beautiful thing was me, allowing my anger to manifest.”

Melissa Febos writes about spending a summer-camp day at an all-female nude beach as a young teen. When a man in a canoe lingers too close, Nadia, the counselor, “strode across the sand, her long body rippling with muscles, breasts bouncing as she marched into the water,” shouting at the man to leave. He did. “There was no self-hatred in it,” Febos reflects here with wonder, “only the righteous fury of a woman who knows she is being wronged.”

In a sense, all these essayists are Nadia, righteously naked on the beach. Some of them bellow and break things, while others more quietly articulate their fury. They examine racism, abuse, gender identity, inherited anger, illness, family relations, and addiction with a glorious abandon—not to mention intellectual rigor.

The takeaway: It’s okay to get angry. With this anthology, Dancyger invites all women to speak out and let the cleansing flames of their own words create the world anew.

—Jane Ratcliffe for Guernica

Guernica: How would you define anger?

Lilly Dancyger: That’s a deceptively tricky question. For me, it’s a strong emotion that comes from not being able to accept something. When I’m angry, it’s usually in direct opposition to something that I’m being asked to just go on with or be okay with. Anger is my visceral, physical, negative reaction to something when it’s not okay.

Guernica: Do you think that men’s and women’s anger is inherently different?

Dancyger: I don’t know if it’s inherently different on a biological level, but the way it’s socialized is definitely different. There’s a lot more space for men to be angry, and for it to be seen as an acceptable—and even admirable—way to conduct themselves. Whereas for women, there’s just a lot less room for us to do that. And so we end up expressing anger as sadness and guilt; we internalize it more. These are sweeping generalizations, of course. But there’s a disparity in our general cultural understanding of who’s allowed to get angry.

There’s a tide that’s turning, where we’re waking up and realizing that, of course, women are angry. And just because we’ve been taught to be nice and sweet, and to be peacemakers, and not to express our anger, doesn’t mean that we don’t feel angry.

Guernica: All that suppressed anger doesn’t just disappear.

Dancyger: One thing that was really interesting about these essays was seeing all the different things that anger turns into. It can turn into depression, addiction, eating disorders, even suicidal ideation or physical illness. Some people believe you can actually make yourself sick if you don’t express it. It definitely doesn’t just go away.

Sometimes it does come out as anger. But it comes out in huge, uncontrollable bursts of anger, instead of in a healthy expression of an emotion, because we’ve been holding it for so long that by the time it comes out, it’s something we no longer have any control over.

Guernica: What do you see as a healthy expression of anger?

Dancyger: To say what’s on your mind, and to speak up when something is unacceptable. Or to speak with a certain forcefulness in your voice that we’re not really used to hearing from women. You don’t even have to raise your voice. Sometimes it’s just a matter of saying, “Don’t talk to me like that,” or “Don’t do that.” Sometimes it’s literally expressing a boundary.

Guernica: For some of the essayists, sadness and anger are linked—at times, indistinguishable. Leslie Jamison’s essay follows her journey from denying she even has anger to recognizing “the ways anger and sadness live together.” Melissa Febos, Marissa Korbel, and Dani Boss also explore this connection.

Dancyger: They definitely are linked. As Leslie Jamison points out, sadness is just a more socially acceptable emotion for women to have. The sad girl is passive; she’s non-threatening; she needs to be rescued. These are all ways that, culturally, we’re comfortable with seeing women. A lot of times, without even realizing it, if a woman feels anger she’ll shut down and just experience it as sadness.

I love Marissa Korbel’s essay. I definitely cry when I’m angry. And it’s not because I’m sad. It’s just this intensity, this flood-feeling of emotion, and it comes out as tears. It’s frustrating, because crying feels weak, right? So when you’re angry, and you’re trying to take a stand and say something forceful, and you’re crying, it feels like you’re undercutting yourself.

Guernica: Many of the writers, yourself included, spent much of their lives forcing themselves to be small. The almost primal necessity to keep our emotions small, as well as our gifts and intellect and general prowess…How do we allow ourselves to be bigger? And what does bigger look and feel like?

Dancyger: I think it starts in small ways. From the moment when a man sits next to you on the subway and tries to infringe on your space—not shrinking physically. And speaking up for yourself. There’s a lot of discussion about this in terms of the workplace. Women being interrupted and spoken over in meetings, and learning to reach for phrases like, “I wasn’t done talking,” or “Yes, that’s what I just said.” Speaking up for ourselves, rather than being steamrolled. Enforcing our own boundaries in public, and in interpersonal relationships. The ways in which you let yourself shrink will determine what you need to let yourself expand.

Guernica: One of my favorite lines in the book is yours from the intro: “Our anger doesn’t have to be useful to deserve a voice.” Even as women are becoming more comfortable expressing anger, there seems to be this underlying belief that anger needs to serve a greater purpose, such as in the #MeToo movement, or the March For Our Lives, or the Climate Strike. I think you’re suggesting we allow anger to simply be an emotion like any other.

Dancyger: That’s exactly it. As we start to make space for women’s anger in the cultural conversation, it seems that’s only happening when we justify it by saying that it’s useful, and that women’s anger can shape politics, can help us reach equality in the workplace, and all that. And anger is a really useful tool, and a really useful fuel to keep us engaged in these big cultural fights. But I don’t like the idea that we’re allowed to feel a whole range of our emotions, as long as we’re putting them to good use. That’s just further sublimation and subjugation. We’re human beings who deserve full access to our emotions, without the condition that we’re using them for the fight. Full stop.

Guernica: The angry woman, especially a woman of color, is often perceived as a threat. Is there “good” anger and “bad” anger?

Dancyger: There are definitely healthier and less-healthy expressions of anger. I’m not encouraging physical violence. But the angry woman, especially an angry woman of color, is perceived as a threat because our [lower status] in society will only be sustained as long as we accept [that status]. The more we push back, and fight for equality and space and recognition and respect, the more we’re upsetting the status quo. And, absolutely, there’s a threat to people who have benefited from women, especially women of color, having a smaller space in the cultural conversation, and a smaller piece of the pie. So they should be scared.

Expressing our anger, when it’s safe to do so, is going to be part of the process of dismantling a whole system where women are so often subject to physical harm when we stand up for our own boundaries. There are a lot of men out there who don’t see women’s bodies as sovereign. So when we dare to defend [our bodies], and deny access to them, that’s seen as an insult and an affront. It’s intolerable.

Guernica: At fourteen, Erin Khar is in therapy confessing everything to her doctor—except for her anger. She writes, “But still, I couldn’t tell him I was angry; I couldn’t let that door open because if I did, the heat below my skin would burn me into nothing.” I think many women are afraid of their own anger. It’s been bottled up for so long.

Dancyger: It can feel scary to acknowledge anger, because sometimes there’s so much of it, and it’s so huge and so stored-up. To acknowledge it is to acknowledge how much in your life is not okay. Anger necessitates action. It necessitates change. If you have that much anger about the state of your life, then acknowledging the anger means you’re going to have to take steps to change it, and to change your relationships and to change your situation. And that can be big and scary.

Guernica: After Rios De La Luz was molested by her mother’s boyfriend, she writes, “I was never scared when I became overwhelmed with rage. It calmed me to think that there was space in my head to see bits of his destruction.” That’s a perspective we don’t often hear.

Dancyger: When I read that line the first time, I was like, “Yes! Exactly!” She’s getting at how anger can actually be really empowering; it can give us something to hold onto, something to fortify us. There’s so much in the world that feels like it happens to you, especially as a woman who’s victimized in one way or another. And it can feel like you have no control. It can be very disorienting; you feel like you’re losing access to yourself and your sense of reality, and to anything that feels like stable ground.

If you allow yourself access to your anger, it’s a solid, stabilizing thing. I know what my reality is. I know who I am. I know what’s okay, and I know what’s not okay. Rios is imagining what she would do to her mother’s boyfriend. Just feeling your own power in that way, even if it’s your imagination, can be really important and powerful.

Guernica: Lisa Factora-Bochers, a progressive Filipina American, finds herself living in Trump territory in Ohio. She’s tempted to move, but instead decides to befriend her anger, and ends up thriving. “Ohio forced me to coalesce anger with a sustainable lifestyle,” she writes. Is this what we should all be striving for?

Dancyger: I put that one toward the end of the collection, because it’s such a developed stage of this process of embracing anger. She’s bringing it into the territory of anger as a political tool, and as a way to stay motivated. Lisa’s essay is a really good model of how you have to do a lot of the personal work first. She talks about her back-and-forth relationship with anger, and trying to outrun it and push it down and pretend it wasn’t there. It was only when she embraced it that it became this sustaining force in her life.

Guernica: Megan Stielstra and Marisa Siegel both write about inherited rage—what they themselves inherited, and what they worry is being passed down to their children. Are there ways to break the cycle?

Dancyger: Like any other generational trauma, the way to break the cycle is to heal your own relationship to anger and find a way to engage with it that’s healthy. And I don’t think that that means ridding yourself of anger. It’s about finding a way to harness it and to give it space, so that you have enough of a symbiotic relationship with it that it doesn’t overpower you and become a toxic force in your life.

I have a fourteen-year-old goddaughter, and I just realized today that I get to send her a copy of this book. I was so excited. I sometimes imagine what could have been if I had understood sooner that it’s okay to be angry—that it doesn’t have to be a destructive thing. When I was a teenager, my models for women’s anger were people like Valerie Solanas and Courtney Love. They’re great! And I still love both of them. But I think it’s necessary and important for girls to see that there are so many different ways to be angry.

Guernica: What happens after we burn it down?

Dancyger: We’ll have to build something new, which might take even longer. I had a really great conversation with Shelly Oria, who edited another new anthology called Indelible In The Hippocampus, which is about the #MeToo movement. There was this huge outpouring of women’s anger, and the world is still fucked-up, right? So expressing our anger didn’t immediately change everything. I expressed some frustration about that, and impatience. And we came to the idea of the slow burn. Now, every time we speak up and share the things that we’ve been told to keep silent, and every time we express our anger, that is a radical act. And it continues to build and build and build. So burning it down might not be one huge bonfire. It might be something that happens slowly over time. It’s the work of dismantling these systems that are so entrenched.