A little over a decade ago, a few weeks after the birth of their daughter, my friend Jason and his wife Krista learned that Krista had a brain tumor. For the seven years that followed until she passed, Jason lived with the knowledge that he and his daughter were likely to lose Krista far too early. A minor side effect of this ordeal was that friends like me were loathe to discuss our personal difficulties, which felt petty in comparison. Jason, whose defining trait is his earnestness, developed a go-to line to combat this instinct in us. “Everyone’s hardest thing is their hardest thing,” he would say. It was a tactic for avoiding other peoples’ pity. But it was also a thesis on the futility of comparison.

Jason’s mantra stuck with me. I placed it on a mental list of “the lessons I’ve learned.” And yet, as the reality of the pandemic set in, it didn’t take long for me to hone my own go-to line, in unintentional contradiction to his: “We’re just lucky that Alexis is the perfect age for lockdown,” I would tell friends and colleagues over endless Zoom calls, speaking of my then-seven-month-old daughter. “She’s old enough to sleep through the night but young enough that we don’t have to worry about remote schooling!” I thought I was simply practicing gratitude until I heard comedian Hasan Minhaj talking to podcast host Sam Sanders about being in self-quarantine with his wife, their two-year-old, and their new baby. I instantly deemed his an objectively more difficult reality than my own. But he pulled the same rhetorical move: “We’re so lucky that the newborn isn’t mobile. If he could somehow walk now, it would just be insanity.” There we were, two dads in our mid-thirties, acting as if imagining a harder thing would make our own hardest thing more tenable.

This particular strain of self-delusion affords one the aura of good humor. I suspect it is especially common among parents, who learn quickly that if talking about parenting is tedious, complaining about parenting is detestable. This is why I instantly understood one of Catherine Cho’s first acts as a new mother. In her book Inferno: A Memoir of Motherhood and Madness, Cho recounts getting an induction, suffering through a long and difficult labor, and eventually having a last-resort C-section. The following morning, her husband James asks her what to say to the friends and family who are awaiting an update. “‘Just say that mother and baby are happy and healthy,’” she tells him. It’s easier than the truth. But the rest of Cho’s memoir stands as a corrective to her initial equivocation.

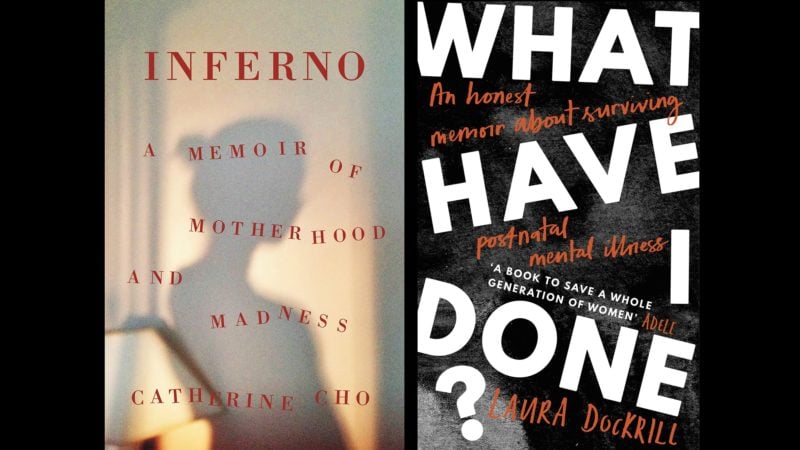

Inferno is one of two books about postpartum psychosis—the other is Laura Dockrill’s What Have I Done? An Honest Memoir About Surviving Postnatal Mental Illness—that have been published in the last year. Both are vulnerable and relentless. It is as if the horrors Cho and Dockrill endured had the side effect of unshackling them from any pressure to hedge or euphemize. Now, having survived the outer reaches of the terrifying territory of new parenting, they’ve come back with maps in the form of memoirs.

Cho’s psychosis sets in a few months after the birth of her son, Cato. She looks at him and sees him looking back at her with devil-red eyes. She hears the buzz of surveillance cameras. She feels walls “moving, closing, pulsing.” She becomes convinced that she and James have descended into hell. She also becomes convinced that it is her job to save James—and that doing so will cost her her life.

Cho spends four days in an emergency room, manic and disoriented, then eight more in a psychiatric ward. There, she feels removed from reality, “suspended in time,” as if she is “caught in a reflection of the world, and there isn’t a way out.” In an effort to break through, she begins writing down things she knows to be true: “I am alive.” “I have a son.” “I have postpartum psychosis.”

It’s a diagnosis she’d never heard of before she received it. “Pregnancy had brought a list of worries—episiotomies, prolapse, pre-eclampsia,” she writes. “I was so preoccupied with the idea of losing my body, it had never occurred to me that I might lose my mind.”

Slowly, the facts of her life drift back into her consciousness. James brings her a photo of Cato during visiting hours. As a form of practice, she walks around the ward pointing at it and telling people it’s her son. “I feel like I am reconstructing myself from my memories,” she writes. Inferno thus serves a double purpose: its text an accounting of her descent, its creation a catalyst in her recovery.

Inferno is constructed as a series of vignettes flitting through time and space. Cho reaches back across continents and generations to try to understand her ancestors. She weaves in Korean fairy tales. She wonders if her suffering is preordained, if her trauma is inherited, if she is stuck in a loop and doomed to repeat the patterns of the past.

Many of these reflections are spurred by her psychotic break, but they’ll be familiar to anyone who has welcomed a newborn. Faced with the challenge of keeping a helpless being alive, we conjure images of our own parents at their most youthful and vulnerable. We then proceed to weigh each decision against the ones we remember or imagine they made for us. We sing the songs we were sung. Or we don’t. Either way, they echo.

Cho and her husband, both of whom are Korean American, live in London, but are visiting family in the United States when her psychosis strikes. The book’s most devastating blow comes when she returns to the UK for treatment and learns that, had she been institutionalized there, she would have been allowed to see her baby every day. Instead, she writes, she had “come back a stranger, and the distance I felt from Cato wasn’t something I could grieve; it went beyond loss. It was a severance, a removal that was complete.” She falls into a deep depression, caused in part by the powerful antipsychotic she was given in the US (and which, she notes, likely would not have been prescribed in the UK). It takes many months of treatment before she is able to become “a mother again.”

The road to recovery is similarly long and tortuous for Laura Dockrill in What Have I Done? Like Cho, Dockrill has an induction followed by a long and difficult labor. She writes of “a primal urge to get naked on all fours and roar like a beastly rhino, sweating and screaming as wee and poo and blood and spit and snot and foul-mouthed expletives howled out of me as I pushed out my little baby.” Instead (again, like Cho), she delivers via unplanned C-section.

Within days, she is sleep deprived. She becomes convinced she is being surveilled. She hears voices and sees stars. She decides she has to kill herself.

She hides all of this from her partner, Hugo. Still, she is eventually hospitalized with postpartum psychosis (in the UK, where she gets to see her baby). After being discharged, she requires many months of treatment before she finds her way back.

What Have I Done? is equal parts confessional, urgent warning, and survival guide. It reads like a mix between a blog post and a public service announcement. Dockrill occasionally pauses between chapters to provide lists with titles like “Things that May Happen to You After You Give Birth that Nobody Tells You About.” At the end of the book, she appends dozens of pages of mental health resources. These include definitions of anxiety and depression and an extensive glossary of mental health and self-care terms.

There’s also an exploration of the little that is known about postpartum psychosis. It can develop as early as labor, but also “any time after.” Women who have suffered from bipolar disorder are at higher risk, but women with no record of psychiatric illness are not immune. According to the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health, postpartum psychosis afflicts one to two out of 1,000 women after childbirth and is associated with a significant risk of infanticide and suicide. But it remains poorly understood. Dockrill calls it “a mysterious enigma of an illness.”

My wife Christine’s difficult delivery experience echoed Cho and Dockrill: induction, long and difficult labor, unplanned C-section. These are just words, of course, and therefore no substitute for the thirty-six hours of needles and IVs and exams and tubes and straps and monitors and fever and chills and uncontrollable shaking and vomiting on the operating table that they signify. More than once, we wondered aloud whether the whole process might not be a bit more comfortable by now if it were men who were required to endure it.

Her ordeal lasted days, weeks, months beyond this. It included an emergency room visit the following week after she began hallucinating in the middle of the night. (Postpartum psychosis was briefly floated as the possible cause, but eventually ruled out.)

Even as I sought to support Christine and Alexis, like a doctor with no training, I began to feel more like a patient with no doctor. My body and mind took on the feel of a Fourth of July sparkler: alight, flashing, about to be extinguished. I nearly fainted multiple times. I sought out desperately needed sleep only to wake up soaked in sweat. I found myself bargaining nonsensically for the health of my daughter with the God in whom I’d stopped believing long ago. I remember having the conscious thought: You’ve never really been afraid before. This. This is what fear is.

I texted Jason, “People don’t talk enough about how terrifying this is.”

“No,” he responded. “It’s absolutely terrifying…People talk about love and joy as much as possible because nothing else can really distract you from natural parental fear.” He wasn’t wrong. The love and joy were there, too. Right next to the fear. Constantly jockeying for position. He added a promise: “you’ll develop superpowers you didn’t know you had quite rapidly.”

Because they are generous writers, Cho and Dockrill both take pains to illuminate the impact of their tribulations on their partners. It is for this reason that, months later, after Christine had recovered, after Alexis had begun eating solid foods, after we had stopped wiping down all our groceries with Clorox wipes, but before the first vaccine was approved, I began retracing my first days of fatherhood, orienting myself by the compasses and landmarks these two writers had set out.

“It changed something profoundly in James,” writes Cho. “The eternal optimist that I knew and loved now has a darkness in him, something that casts a deep shadow.” In one scene after she has been released from the ward, she watches James pack an emergency bag in case she has another episode. She tries to convince him it isn’t necessary. He doesn’t listen. “He wouldn’t be caught off guard again. He had been shaken…his sense of control had been lost.”

Dockrill reveals that Hugo eventually suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder following her ordeal, which comes “in the form of twenty-four-hour panic attacks. I guess he had been our guard dog, protecting us all throughout my postpartum psychosis,” she reflects. “Now that I was better he could settle—but his mind and body were on some frantic adrenalin overdrive from what we’ve been through. Suddenly, it was my turn to take care of him.”

“My partner Hugo says if he could share one piece of advice from our experience, it is this: speak up. Talk about what you’re experiencing,” adds Dockrill. Cho echoes her: “James and I talked about those days until it didn’t frighten us anymore.”

Talking has certainly helped me: Talking with Christine, my family, my friends. I even picked up a few new terms in Dockrill’s glossary—”magical thinking,” “intrusive thoughts”—to talk about with my therapist.

As far as I can tell, Alexis doesn’t get scared when we put on our masks. I like to think that’s because we’re taking proper care of our fear. She focuses her attention instead on whatever is most novel in any given moment, whether it’s an unpeeled banana, an open door, a piece of mulch, a pocket, or a pebble. She’s developed a mean repertoire of animal sounds. She has come close, on several occasions, to saying the word “icicle.” And sometimes, after she puts her giraffe-shaped toothbrush away in the medicine cabinet, she waves to it and says “buh-bye!”

I reached out to Jason recently to ask if he remembered that time when I’d texted him to ask why no one ever talked about how terrifying this all was. He said he did. Then he said, “It kinda just stays like that too, though.”

He was right. Parenting still was, still is, terrifying territory. But to numb the fear would mean numbing the love and joy, too. Unthinkable. And so I’m doing my best to let it all in. Maybe that’s what he’d meant about superpowers.