Crones, Hags, Witches, and Killjoys consists of short letters between two writers/mothers/feminist co-conspirators in Portland, Oregon, as part of an ongoing conversation we’re having—not just with each other, but with artists, activists, and troublemakers across time and space. This two-year dialogue delves into sexism (institutional and internalized), ambition, ambivalence, capitalism, motherhood, art-making, child-free-ness, selfishness, self-sacrifice, backlash, and the many uses of rage.

There will be no more ink for pedophiles and cock-waggers. We must archive women’s voices. In response to current national conversations about abortion, equal pay, domestic labor disparities, transmisogyny, sexual harassment, and assault, we are spotlighting the witches, killjoys, crones, spinsters, dykes, and nasty women who have been calling bullshit on misogyny for a long, long time.

The authors dedicate this piece to those who have lost their rights to abortion in Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, Ohio (and the list grows).

*

It was supposed to say “Great Artist” on my tombstone, but if I died right now it would say “such a good teacher/daughter/friend” instead; and what I really want to shout, and want in big letters on that grave, too, is FUCK YOU ALL.

—The Woman Upstairs (Claire Messud)

4 December 2017

Dear LZ,

We met in a windowless classroom almost exactly five years ago. We both had jumbo milk lumps where our dry breasts used to peacefully exist inside our garments. I was bleeding; we were both healing from our stitches and stretches. Our kids were infants, six weeks apart. I brought my daughter to your grad fiction workshop and nursed her, through your firm and steady voice managing some guy across the table from me trying to turn every conversation into a battle of wits. He quoted Borges and inserted himself into things rather than asking questions; sharp elbows, condescending smile, summer scarf, dumb mustache, vacant. I remember you gently reminding this dude, a few times, to turn in a writing sample as part of the requirement you set for undergraduates entering the course. You seemed unsurprised when he stopped showing up. He was working on his novel. We were lady writers raising babies and asserting our space within a world of self-obsessed men who were alternately blind to our circumstances and happy to scrutinize us.

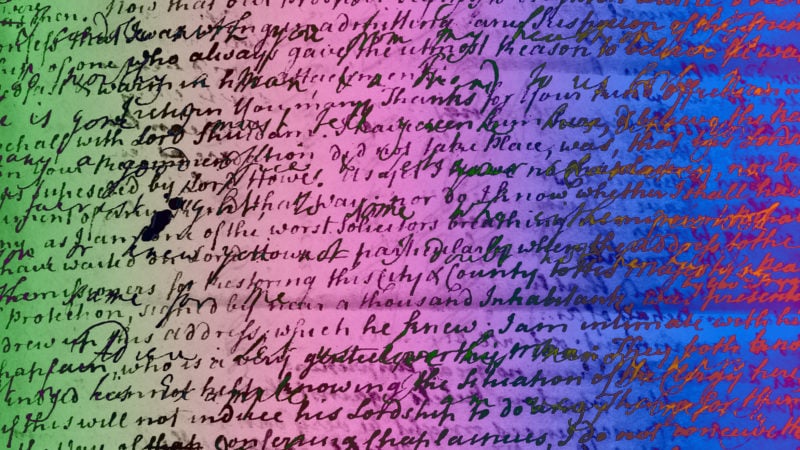

When I sit down to write you these letters—in the long tradition of women scribbling away their “dirty” thoughts, furiously, like polishing silver to reveal mirrors for each other—a polyvocality provokes and pushes phantom words from silent throat to keyboard. I am not alone. We are not proud of our singular and original thoughts. They are all for other women. They are all for each other. Our legacy is that of finger-wavers and plate-smashers—bitchy and bruised from a distance, but wise and determined in our eyes—who say, “It would be a great time for men, basically, to go on vacation. There isn’t enough work for everybody. Certainly in the arts, in all genres, I think that men should step away. I think that men should stop writing books. I think that men should stop making movies or television. Say, for 50 to 100 years,” like Eileen Myles did. I also think of Jessica Hopper, Yoko Ono, Rebecca Solnit, Bernadette Mayer, Kathy Acker, Kathleen Hanna, Lee Miller, Marguerite Duras, Sabina Spielrein, Angela Davis, Vanessa Bell, Aileen Wuornos, Doris Lessing, Sara Ahmed…the roll call of our dreams to counteract the nightmares of “jobs” and jobs filled with the grime and sludge of a toxic masculinity we have barely begun uncovering. It is a brutal red winter of our feminine discontent; our bodies left out in the cold. Here’s to the cover crop of crones, hags, dykes, witches, and killjoys who went hoarse screaming out for a revolution at every door that was shut in their crimson faces.

XX,

S

18 February 2018

Dear S,

A warty cluster of obligations has delayed my answer to you. I feel bad for this. Vaguely, pricklingly guilty. It’s a familiar feeling—I’m in a long habit-trough of putting off the important (such as connecting with you, my fellow writer and mother, my comrade and collaborator) for the sake of the urgent (emails answered, travel arranged). If we were talking face to face, ice cubes melting in our drinks, I know you’d reassure me, wave off my guilt. We all do it. The recognition of shared failure is crucial to our friendship. And maybe “failure” isn’t the right word. Maybe I mean “mothering.” Or “demons.” Or “pursuit.” Whatever the word is, five years ago—milk-drenched, hot-eyed from no sleep—we saw it in each other.

Writing to you makes me think, of course, of the women who went before us, who slogged and trudged and scratched out a path that we might walk it—run, if we’re lucky. We are lucky. Your book is coming out soon; mine just did. Which requires more than luck, of course, but luck must be mentioned; otherwise, we’re as deluded as any white guy who thinks he won the race (got a job, received a prize, walked down a street unbothered) through effort and talent alone.

The genius killjoy Audre Lorde would have turned 84 today. I think about her gifts and weapons so much these days. This passage from Sister Outsider is a map that bears daily repeating:

Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucible of difference—those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are black, who are older—know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structure in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish.

Which witches are most on your mind right now?

xx,

LZ

4 April 2018

Dearest LZ,

I just read a passage about the movie Times Square in Michelle Tea’s new book, Against Memoir, that made me think of you:

For Nicky, a nobody, someone who risks falling through the cracks daily, who arguably already has, safety comes from being seen, and fame offers the ultimate protection, artistic fame in particular. She wants to be a rock star—she is one by nature—but like so many cast-off queers of past generations, there’s no path for her. Pammy, with her wider, class-based belief in possibility and her understanding of opportunity, nurtures Nicky and pushes her to actualize her dream.

The two girls, Nicky and Pammy, are from very different socioeconomic backgrounds, but share a lust for a life that often results in graves or invisibility after humiliation, or a kind of notoriety that incubates powerful male legends and couches women as hungry, unbearable, whorish, vampiric. Times Square doesn’t end much better than holding hands and driving off a cliff in a classic car, but before the female love swan-dive (that you and I will work to resist), we watch Nicky and Pammy share their writing with each other, both proud and ashamed, unshrinking their psyches and moving out of dark corners. Are you openly allowed to desire the expansion of your worth through writing a book—ravenous artistic worth that isn’t tied to your friend, partner, teacher, mother, neighbor, caretaker role? Or is that an erasure and playing to macho culture? The way men never seem to have enough vulnerable private conversations, but get up on stage and all of a sudden express their feelings and then call this rage or sadness art?

I’m thinking of your “luck” and upcoming book tour—you are truly in the zeitgeist because of some stardust feminist alchemy—community, support at home from an informed and responsive partner, as well as, of course, the braised eyes on the text with cranky wrists on a keyboard for hours on end. It has been my experience that you are a listener who makes other writers feel as though they have the invitation to appear: one foot in whom they had always been, but forgot about, and whom they have meant to become, fearing the price.

I am also thinking of our artistic foremothers and having the right to name your own baseline, your own success and failure models. My lingering disgust and dread of hunger or lust, our middle class fault lines, our striver fathers with career and work ethic expectations, our mothers who learned to adapt and unsee to survive—we live with this polarity of too close to the sun and buried in the cold ground on a daily basis. We are torn. I loved seeing that Joy Williams—whose salt feels like sugar on my wounds—speaks on the cover of Red Clocks, seeing you, the years you inhaled her hours pushing a pen, longhand, now a full circle. Right now I am courting witches who were friends within their art, within the resistance. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson braid the hair that stands on the back of my neck. What texts have you seen with a version of Sylvia and Marsha? Who are your favorite crones, loners and outcasts?

XX

S

20 July 2018

Dearest S,

I once drove Grace Paley from Vermont to Massachusetts for a literary conference. I got pulled over for speeding. While we waited for the cop to take his menacing time getting out of the squad car, Paley said to me: “It’s okay. Who cares. I’ll pay the ticket.” Her kindness jarred me. Here was a woman whose sentences had shaped my understanding of what fiction was capable of—whose wry brilliance on the page was (still is) a North Star for me—and she was also caring for me off the page? It felt so good that I didn’t trust it.

* * *

Picking up this letter again, after many weeks, I wonder what else I was going to say about Paley. That she was otherworldly in her compassion, her lack of ego performance? That I was incredibly lucky to meet her?

I’m thinking tonight about a quote that’s gone—well, maybe not viral, but as viral as literary book Twitter gets. It’s from an interview with Lauren Groff in the Harvard Gazette:

GAZETTE: You are a mother of two. In 10 years you have produced three novels and two short-story collections. Can you talk about your process and how you manage work and family?

GROFF: I understand that this is a question of vital importance to many people, particularly to other mothers who are artists trying to get their work done, and know that I feel for everyone in the struggle. But until I see a male writer asked this question, I’m going to respectfully decline to answer it.

A lot of people are tweeting, retweeting, Instagramming the excerpt with clapping emoji, heart emoji, comments like “Preach!” and “This is how it’s done!” and “Lauren Groff for the win.” I, too, felt pleased when I first read it. I liked the resolute thump of respectfully decline to answer it. Something has been nagging at me, though, about the consensus celebration. About the fact that we all agree how wonderful it is, Groff’s refusal to answer—how good it makes us all feel. By not answering, Groff calls attention to the gendered double standard built into most discussions of writing-while-parenting. Yet a consequence of the not-answering is that the question isn’t explored. And it’s an incredibly important question. I don’t think Groff herself is obliged to do it, but how do we want to see it explored, in the wider cultural conversation? How to wrestle with it without falling back on sexist binaries and “lean in” clichés? Until I see a male writer asked this question. Men rarely get asked, of course, because everyone already knows the answer. If a man writer has kids, women are taking care of them. His wife or girlfriend; a nanny; a daycare teacher; his own mother. Paid or unpaid, the childcare gets done.

Women writers with kids have a far more complicated relationship (individually, collectively, historically) to how it gets done. How much of it are we doing ourselves? Should we be doing less of it? More of it? How guilty do we feel about paying another person (usually another woman) to tend our children? How angry do we feel about not having enough writing time because we are tending our children? How does our partner, if we have one, figure into the labor division?

It’s also been a day of crying, but more on that another time.

Love,

LZ

2 January 2019

Dearest LZ,

I have been underwater with rage, and then, when the holiday season of hellish demands hit, of making fake magic, of wrapping paper cuts on my very red eyes (hallucinating, not slouching, towards my bed) there I was with just a dry sink of dishes and worn-out disgust. I can’t stand how little seems to change and how we are forced to recycle the news like bottles with no deposit. Yesterday, last week, last month, we were seething and we were brimming with compassion when the kegger-boy rapist got confirmed on the cartoon network of making decisions about my, her, your, their body and mind. It seemed impossible that there would be another abhorrent blow to our bodies, our feminist work, to our legacy of survivors—the traumas that made activists. How strange that a man got to cry and tantrum and blubber like a silly child with a cryptic, yet grossly obvious, calendar of what amounts to boring dick pics and pats on the ass, all while being interviewed for the most demanding and prestigious job in America—besides the one being held hostage by his rival in indecency and disorder.

I have been reading di Prima and the newly released Plath letters, and probing another way of asking how and why and IF we should entertain the “motherhood vs. artist” questions at all. How cruel and how mysterious can it really be? The shaky answers are: never learn to type, get a secretary, ask for help from other women, have more orgasms at any cost, stop being polite (again), make more money and pay for more childcare, fight for free childcare, have better access to safe abortions, help more women, elect them to office, and not one man will change or notice if you sacrifice your ambitions.

On Paley, our Grace:

I was at the Strand, in the 90s, and I flipped through a copy of the Paris Review, on accident, because I inhaled the magazine section to girl-torture myself with shit I can’t afford and to try to find some idols to imitate (Oh, Sassy) and wanted to know what Europe, mostly France, thinks of things. A gas. I began reading an interview with Grace Paley that I didn’t understand one bit. But a few major things happened immediately: I could see with my own eyes the places in NYC she described while living her life as a single mother of two kids; an Eastern European Jew, like myself; and a writer who told the truth about coming into her career later in life, writing in fits and starts, almost accidentally, devoted to activism. I didn’t read her work until I became a mother. Until then, I roamed, and would always choose self-sabotage or solitude over competing for anything that another girl or woman might want badly. I was partly an ambivalent stripper due to this attitude of guilt through accomplishment. Oy vey. Now, I get to celebrate and support other women whose writing I love, without cutting myself to shreds. In a month we get to do our event for my book launch. What bliss.

I made myself a list to share with you and to wish you a Happy 2019.

- We are very much exhausted, but we have each other.

- When you tell me to not be sorry for crying, I know I am allowed to like my most vulnerable and soft parts. I am alive and not just surviving.

- I am lonely, I am a nag, I am a shrew, and I won’t get punished as badly for any of it because of our love and solidarity.

- Our hunger and need for each other and our work will not protect us from grief, but it will fortify us for the next day.

- When they sensationalize our struggle only to toss it aside the next day, we will make it immortal in letters.

Love Always,

S

19 April 2019

Dear S,

I’m thinking of an email you sent last month: “I’m around this weekend if you wanna get tea or join us for Purim. It’s actually a really important holiday for challenging ableism and notions of reality!” So grateful (me) to have a friend (you) who invites, gathers, celebrates, remembers, and skewers ableism and reality in the same breath.

Another holiday is coming up—good old fucking Mother’s Day. Not known for challenging received notions of reality. More like known for fetishizing domestic virtue and flattening into paper-doll simplicity a role that is tangled and wildly various. I wish we could skip it this year. I mean, we can, as individuals, but I want the whole country to ignore it. I don’t like sitting in the room of virtuous simplicity. Where is the room for unvirtuous complexity, ambivalence, and being exhausted?

How are you feeling about Mother’s Day this year?

Love,

L

21 April 2019

Dearest L,

We missed you at Purim! A holiday where vulnerability is encouraged. We all play and honor the fool, and we wear masks to challenge strict realities of who gets to be in charge. Mother’s Day is a joke we are all in on, and yet it continues, straight-faced, the straight-man comedy-duo sidekick to the silly and sweet Father’s Day. Mother’s Day feels deadly serious and poisoned. If I wasn’t motherless, I know that I would still hate it, because I am in possession of my killjoy faculties at all times and refuse to be pacified or anesthetized through a forced ritual of appreciation one day a year. Having to smile through it in gratitude is more vinegar on the flies dead in the honey jar. I didn’t want to catch more flies, mind you; the sugar was not my own, and I have an excess of astringent, bitter, complicated, and far more delicious to me—a way to attract a coven of honesty rather than a pretense of sweetness. Yeah, I am a mother who kisses my daughter’s still chubby hands, sneaking into her bedroom at night to shed a tear and rub that sweaty palm on her own cheek because a transformation is inevitable, because I miss her baby days, because she is asleep and reality isn’t so real. Underneath it all, though, I am as tired and grossed-out with the lack of support or understanding or resources for all mothers who are not rich. Well, even they can’t deal, won’t deal, are hollowed out by nurture torture as The Woman, and are tricked into hating other women in return.

I face this Mother’s Day ambivalently pregnant. I just found out that my body is splitting cells and making my boobs rip at the seams and throwing sand in my eyes and wiping me out. I do not know what I will do. I have had positive experiences choosing to end a pregnancy and hope that this option is available to me in the same way, and will be available for other women indefinitely, will become less of what Anais Nin calls “a racket,” and that we all fight for it to be completely normal, practical, fully covered, and with no added anxieties, no pressures, no taboos, no daddies, and women talking-to each other openly. No more bootlegging for our tissue cells. I don’t have a secret, and yet if I told everyone who asked me how I was doing at the Seder I just attended and I said, frankly: I am pregnant, actually, and I don’t yet know what to do, but leaning towards termination…I do not know if I could stomach being the needle scratching the record, or the long hair in the potato salad, or just deemed too crass, but I think I would get the big nothing back. We stonewall women who talk about their bodies any-time-any-place as they are living in them in real time. Currently, I am pregnant. I am alone. I don’t feel like it is safe for me to be truly vulnerable, or rely on the person who is the other half of this equation. I have two children already. So does he. I have no parents around to help me. My insurance deductible is way too high. I have maxed out my credit cards and I have to leave tomorrow to finish out the Mother Winter book tour, which I have cobbled together and mostly funded myself. Why would I want the phony glamour of the mani/pedi and pesticide roses and being told that, Gee golly, I can sleep in today, like I earned a day in the yard after 364 days in solitary.

I am thinking of how fucking broke and brilliant Bernadette Mayer is and how she must have been judged hard for having that third kid with no dimes to rub together. Was her partner judged? Or was he just stoic and virile? A good brag to have at the bar. Going to the bar any old time he wants, yum that wine tastes good, isn’t life a gas. He can hide anything. She can’t. I am thinking of Doris Lessing having her third child after being shamed into giving her first two kids away to what looked like a better nuclear family deal to the world, to the world that had no concept of co-parenting, not yet; to her third kid playing under her feet as she wrote and wrote, hated and wanted and needed by her other kids. Stranger, mother, artist, screwed, always screwed. I have time to weigh my manifesto against sugar comas and motherlessness and saying, “maybe,” when my whole life the gun to my head was loaded with whatever the dude needed or feared most and I had to just wait for his arm to go numb, for the hand to shake, for his trigger finger to get weak, for him to stop pointing at me with his eyes closed, my stare forward, breathing rhythmically, never putting an end to his cowardice, never managing well beyond this stand-off.

I want free day care and the right to be angry in public without being told I am rude or a child. I don’t want pity or trepidation. I do not want a reminder that this may be my last chance to be seen as a saintly erasure (with new baby) or an erasure-erasure (abortion). I keep wanting to ask you what you would do if you were me but that is so beside the point. Just like Eileen Myles telling me “we are all motherless,” I do believe this riddle is deeper than my shame, bigger than my womb can hold. What will you do to get away from Mother’s Day? What’s the main ick for you?

Love always,

S

21 April 2019

Dearest Sophia,

You can ask me what I would do! Maybe you just did. My truest answer: I’m not sure. I remember my own oceanic longing for a baby, for that joyous creaturely intrusion, that softness and strangeness. I understand your longing. I also understand your inclination to terminate. I am glad you have a choice, but I don’t presume the choice is easy. Our roads have been different—I went through all the infertility shit and did IVF to get pregnant with Nicholas. I wish we lived in a world where this decision could be talked about openly, matter-of-factly, as it’s unfolding. An ordinary part of life. I wish you could have felt, at the Seder, able to share.

Your book tour is taking you to a state whose legislature just passed a “Heartbeat Law”—another of the thousand cuts that may kill us. Destroy the right of any impregnable person to bodily autonomy. In Ohio they’re recruiting volunteers to drive people across state lines for abortions.

Impregnable also means “strong enough to resist or withstand attack; unconquerable.”

When we moved this letter-writing project from Docs to Hangouts, I found a note I’d tried (and failed) to send on Hangouts on November 28, 2013. It reads:

Dear Kyle, I’m the mom of the baby you stopped to help on the highway near Ellensburg, back in September. I want to say thank you for your kindness. Our baby, Nicholas, is doing fine. He is now taking medication for seizures. I will always remember you for stopping to help us. I wish you all good things in your life. Happy Thanksgiving!

We were driving north on I-82 through the Yakima Valley. I’d been invited to read at a book festival in Mazama, Washington. Nicholas had his first seizure in the back seat. I thought he was dying. Would die. On the gravel shoulder of the highway. A guy saw me screaming and pulled his car over and said he knew CPR from lifeguard training. I handed him the baby. It was the worst day of my life. That day I understood, or began to, that being his mother would not be like any experience of motherhood I’d imagined. Which, I guess, is true for any parent: we can’t know in advance what will be asked of us. Can’t preorder a life free from watching your ten-month-old son have a seizure, the first of many, on the side of the road.

The main ick of Mother’s Day? Its surface is too smooth to hold that hot, hideous moment on I-82. The moment slides right off.

I’ve spent today blowing my nose, swallowing Advil, and listening to Nicholas yell his head off because he has a cold, too, and a front tooth about to fall out. We are both pissed as vipers. I admire N’s ability to inhabit a mood 100 percent honestly—he never hides his discomfort in order to make other people comfortable. I hope he’s strong like that his whole life.

You know this already, but—Bernadette Mayer named one of her daughters Sophia.

Love always,

Leni

4/24/19

Dearest Leni,

I remember when N had the onset of seizures and, finally, when he was put on meds and you began to process your new reality—sharks in the bloody water when you thought you were in a clear swimming pool. We were in your school office shortly after they mercifully tapered off and talked about EMDR and about saving what’s left of your sanity, trembling with your own after-shock, caught in the net of helplessness, too scared to be sad yet, too wired to sleep; for what could happen if you closed your eyes—that hypervigilance slightly mitigated by holding buzzers in each hand and going through the story again with a therapist to contain the reheated jello of your insides. Then, again. Aura. Nausea. Speechlessness. Worried. Mother. Teacher. Unready.

Franny was about four or five months, Nicholas maybe seven, when we briefly hung out in the lobby of The Armory during the Oregon Book Awards. The Listeners was nominated. You didn’t expect to win, generous and skeptical as usual. We chatted about our babies, yours safely home with his dad, mine pooping and squirming in my sling, and someone quite deserving got it instead of you; so be it. Winning isn’t actually everything. I loved that book, but you had another one cooking already. And through every test N had in the works, and every student meeting, and our tea times to discuss occupational therapists and speech therapists and evaluations, you managed to finish Red Clocks. Last night you won the fiction award, and I wrote to you and to anyone I knew who attended to make sure the world was right. It was. All while I was pregnant and despondent, walking around the heartland of America, where abortion is all but illegal due to the Heartbeat Law, the anti-science, the OB-GYNs who refuse basic care and comprehensive reproductive services to women who dare ovulate and have sex for pleasure, hiding my body’s reality at a small college in Ohio, about to lecture on my perennial Mother Winter topics: men switching to nurture professions and letting the women run the arts, free abortion on demand, free daycare, and the constant chokehold around a mother-neck, there to squeeze like a stress ball, there to coil round your now-solid fontanelle like a swan protecting the mind from harm, blamed when you see the truth and feel the bumps and bruises anyways. I couldn’t tell the truth about myself unless it was confetti-in-the-air kinda news, which I can’t guarantee. The shrew. The hag. The nag. The desperate joiner-outsider.

I’m so proud of your book and where it will take you next after this well-deserved prize. Oregon is so very rich in splendid authors, and you earned the leadership role—a literary matriarchy. May it unfold horizontally and give courage and chutzpah to other girls and women. May you not be too depleted and forced into a neverending Mother’s Day parade, a receiving line at your so-called book wedding, married to what is deemed success. Why can’t success be allowed to be sleepy, like us with our babies? Why must we be Joan of Arc’d into roles of council in robes? When will NO be a complete sentence; not a sentence to be the ogre with tits, Baba Yaga, platinum bitch status? Though it’s also a badge of honor to be all of the above.

I want your body to know warm wind on muscles that don’t twitch, free of any guilt, very soon. I want N to keep being the truest face in every room, visible to the world as the badass he is; that moxie, wisdom, persistence. His eyes are so big, just like yours. He sees all. He sees you. I can see you look up to the ceiling, think and nod along before you speak. Girl tongues.

I’m now flying home, where I can get an abortion at the same doctor’s office where Franny was born—if I decide to—seemingly static over snowy mountains, crying baby and patient mom next to me. I love this (every) baby. I really love his foot digging into my thigh and can’t convince her to stop saying Sorry. If I wasn’t needing to be stoic and calm in my storm, I would offer to hold him. He keeps reaching for me. I keep making him laugh. Some pervert creep like Pence would say it’s a sign from God of my life growing inside, giving me a signal for him to legislate. Where’s the responsibility on those who spread their seed like crop dusters? But me, I must keep the growing tissue cells incubated and give birth this December, 41 and with no secure income, terrible health insurance, CPTSD, and a child with ADHD, sensory processing, and learning disabilities who needs me to not have postpartum depression, who will manage if having another child is what’s right for ME, but I can’t move an inch in either direction yet so I am here in the middle, stuck. I must finish the tour. Suspend most other promo responsibilities and feel through my seasick blues and colossal elation of progesterone, which is the movie-reel image of a naked tummy healing from my placenta cord gone by, right before the stupidity of Christmas, a holiday when I always deliver my magic to the kids, against my own values or deep rage at capitalism, shiny, embalmed, same every year, frankly, dead. Mothers, get into your tombs.

I think I should start working my body into everyday basic conversation. Before I left for Ohio, they asked me how I’m doing at my local coffee shop. I said, I’m really out of it, I’m pregnant. They didn’t hear me. I repeated it three times. Pregnant. It’s ok, I reassured. I don’t have a gun, just am in between a yes and a no. I really care about these people I see every day. Too much for a coffee line, I guess, but I was trying out being the living sad, not the living dead and shut down. I don’t think I should be forced to be private when my body is a gavel away from being mandated to keep growing or be arrested. The Plan B pill that failed may someday be outlawed anyways. Most women I speak with haven’t even been educated on what it actually does—that it only keeps you from ovulating, not from implantation if you have already released an egg.

All I keep thinking is—how would I get on the daycare waitlist? What’s five years of that without the student discount gonna cost me, the third time around? How will I write my next book? What if I save myself but can’t write for some reason? Double bed of useless. Bad woman. Bad artist. I want I want I want.

Next week you are interviewing Miriam Toews. One of her protagonists in Women Talking reminds me of another reason I should preserve my body, time, and mind; she says something like: the men wanna use us until our wombs drop out of our bodies on the kitchen floor. Wrung out. You say, husk. I say, shell-shocked. Going down down down, our wombs. I so want you to come into that conversation knowing you have made important art, shepherded great art, and you have been a beacon for women whose fates you don’t share. Our feminism is for everybody. Every. Body. It is the kind of conundrum I sit with on this plane right now. You were throwing every possible tear and resource at your infertility and yet, you told me, this is us doing what our cells allow, it’s not your fault or my fault. Me having one or not having one can’t solve any woman’s (or man’s) reproductive struggles. Every choice offered. But not every wish granted. That’s the motto for our wombs. What will you ask of her, her women talking? What do you want for yourself next? In talk and in action.

I love you,

S

4/25/19

Dear Sophia,

Back in January you sent me a New Year’s list. I love your list for not averting its gaze. It sees the shitty along with the good. One of the thousand things I cherish about you is your stamina for, and insistence upon, this kind of clear-eyed attention to the whole of it—fear, love, shame, feminist solidarity, fecal explosions. You face things even when they’re at their bloody shrieking worst.

Here is a list for you, written in Oregon on a Thursday in April:

- You are pregnant, exhausted, uncertain, and fiercely loved by many. From N. on the third floor to me across the river to E. in Texas to S. by the Jersey sea, a LOT of us are in your corner! And we’re not going anywhere.

- We are often angry and afraid, but we’ve got each other.

- And we have many, many mothers. Some are ghosts.

- In a society without enough space for bodies or minds that disrupt the norm, we will make space for each other, for our children, for our friends, and for people we’ll never meet who deserve space too.

- In the secluded-hetero-nuclear-family loneliness of patriarchal capitalism, we’ll forge ties of all stripes that defy this isolation.

- When they pretend to listen to women talking only to forget every word the next day, we will make our talk immortal in letters.

Love always,

Leni

4/26/19

Dear Leni,

About to leave for Nashville. Party! Books!

I got an appointment for this Wednesday to speak with my doc about my options. An hour ago I made up my mind to ask for an abortion at my OB-GYN’s office (safer than childbirth by a wide margin despite psycho-Bible-babble). I think they will schedule it to be done sometime around Mother’s Day. I have to factor in my days off so that the kids are with their father and I can rest up and watch movies in bed. That’s more space to heal than most women will ever get, and I do not take it for granted. I never will again.

The ex-lover I still pine for deliriously won’t call me to make sure I am well. I know you’ll come with me if I need you to. I am sad but no longer scared or confused. I feel loved in ways that are easy to forget about, and I am grateful you have reminded me to look around and take stock. I hope you feel it, too. Love you. Onward.

Yours Truly,

S

27 April 2019

Dear Sophia,

I will come with you to the doctor, if you want me to. I will bring over snacks, iced tea, and maxi pads. I will take Jake and Franny if the schedule with their dad doesn’t line up exactly. Things you’d do for me without blinking. I’m reading Miriam Toews’s All My Puny Sorrows, which is full of women accompanying one other through life—sitting vigil in psych wards, running errands, attending funerals, telling jokes. All of it.

Onward we go, together.

Love always,

Leni