Sandro Miller unwittingly—and somewhat unfortunately—created the perfect viral art exhibition.

“I’m never going to put images out for hits on social media—that’s not who I am,” the 57-year-old photographer told me, contrasting his methodical, research-heavy camera work with a generation of Instagrammers. “But because of social media,” he added, “my project went worldwide instantly and hundreds of millions of people saw it overnight.”

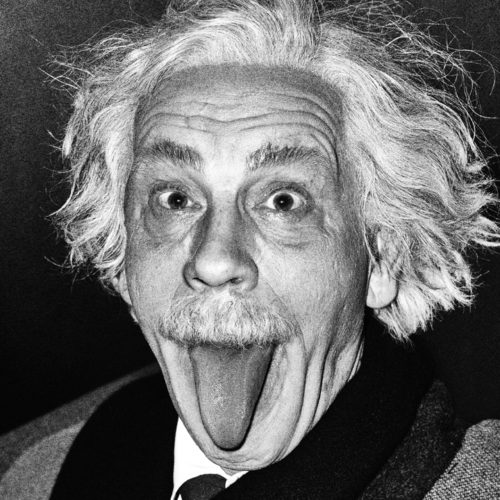

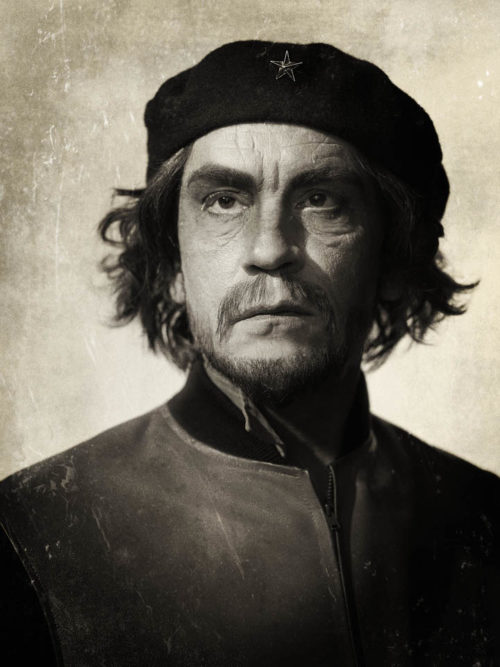

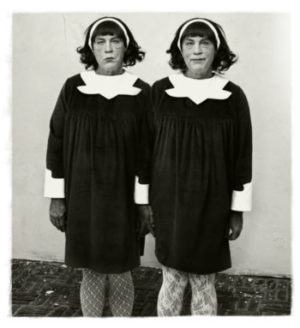

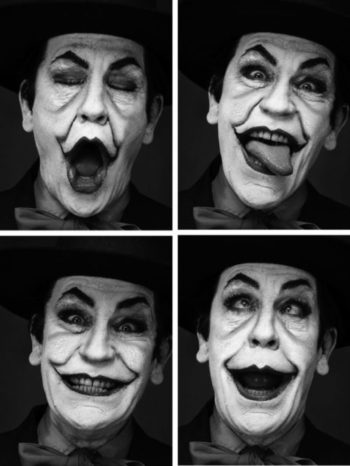

That project would be “Homage: Malkovich and the Masters,” on view now through July 1 at Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York. The show features Miller’s recreation of forty-one iconic photographs originally taken between 1905 and 1990, all re-cast with John Malkovich as the subject. There is Malkovich as Einstein, sticking out a triangular tongue; Malkovich in double, dressed as Diane Arbus’s famous twin girls; Malkovich as Marilyn Monroe, as Meryl Streep, as Dorothea Lange’s migrant mother.

The Chicago-based artist, who has also directed commercials and short films, first showed four of the images at EXPO CHICAGO in 2013. They were an immediate hit. Visitors lined up to see the works, Miller said. The media thrilled. (From Business Insider: “These Images Of John Malkovich Recreating Iconic Photos Will Blow Your Mind.” From Huffington Post: “Artist Recreates Iconic Photographs With John Malkovich, And It’s Fantastic.”) “My business changed because everybody wanted to know about these images,” Miller said. Since then, the photographs have been exhibited from Los Angeles to Warsaw to Amsterdam, and a book of the artist’s collaborations with Malkovich—they have been working together since the 1990s—was published in April under the name “The Malkovich Sessions.”

Contemplating mortality, Miller devised a tribute to the men and women who had first inspired him to pick up a camera.

Ironically, however, Miller never intended to blow up on the Internet. Instead, he wanted to cultivate an appreciation for the greats of photography—and for photographic rigor—in a generation too attached to digital manipulation and thoughtless smartphone snaps. In 2011, he was diagnosed with stage-four cancer. Contemplating mortality, Miller devised a tribute to the men and women who had first inspired him to pick up a camera. “If I make it through this whole thing, can I say thank you somehow?” he wondered. “Maybe I could get younger photographers to start thinking again about these classic, classic images.”

He came up with roughly forty images that had lodged in his brain and set out to recreate them. He asked Malkovich, whom he had met while working for Steppenwolf Theatre Company when the actor was an ensemble member, to be his subject. “He understands direction, he understands light, he understands the camera,” Miller said.

All told, the project took about a year and a half, including months of research, Miller said: blowing up the originals to glean the exact stitch on a collar or the type of lighting reflected in an eyeball, interviewing the few photographers who were still alive, and perusing contact sheets whenever possible. Miller worked with a set builder, lighting designer and makeup artist. For Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ,” he lashed Malkovich to a twelve-foot cross and submerged the resulting photograph in his own urine, which he had collected over three weeks. (“My wife was not happy with me.”) His only digital manipulation was to retouch some of the images to get the appropriate graininess for their age. “It’s a crazy, crazy, crazy undertaking,” Miller said.

As an actor, Malkovich has had practice impersonating others, but he has also played himself impersonating others.

Editors, however, continue to focus on Malkovich, a fact to which Miller seems resigned. Malkovich, after all, is the perfect subject for the Internet age—recognizable but not tabloid fodder, an acting heavyweight with a sense of humor. And then, of course, there is Being John Malkovich, the 1999 movie starring John Cusack as Craig Schwartz, a schlubby puppeteer who finds a tunnel to Malkovich’s brain hidden behind a filing cabinet in his office. At one point, Malkovich goes through the portal himself, descending into a restaurant where every person looks like him and all anyone can say is “Malkovich,” over and over again. As an actor, Malkovich has had practice impersonating others, but he has also played himself impersonating others. Cameron Diaz as Craig’s frizzy-haired wife Lotte sums it up best: “What is this strange power Malkovich exudes?”

Miller said he never thought of the film while putting together “Homage.” “Most people who understand art will tell you that this is a photographic project that John Malkovich happens to be in,” he said. He attributes the global attention to the quality of the recreations, and that undoubtedly has something to do with it. There is a creepy thrill to watching the 62-year-old actor disappear into so many bodies and styles and time periods. The images also raise thorny questions about photography: What does it mean to painstakingly restage snapshots and magazine photos for a “high art” setting? Are these the “right” images to populate a photographic canon? Do photographs gain or lose their power when they become icons?

However, because the images are so well known, they are easy to appreciate on a surface level, easy to Instagram. This is their power and their downfall. The unfailingly polite Miller said he was glad for the recognition that the Internet gave him, but he also pointed out the cheapening effect of social media: “People think once they’ve seen it on their phones, they’ve seen it.”