As a Midwestern teen and dependable babysitter, I was the kind of girl you’d expect to listen to bubblegum pop. But the moment my charges were asleep I’d flick on MTV, where the late night shows were increasingly featuring a band called White Zombie. I had to keep the volume low: the driving riffs buzzed and rumbled like a rhythmic, jet-sized yellow jacket.

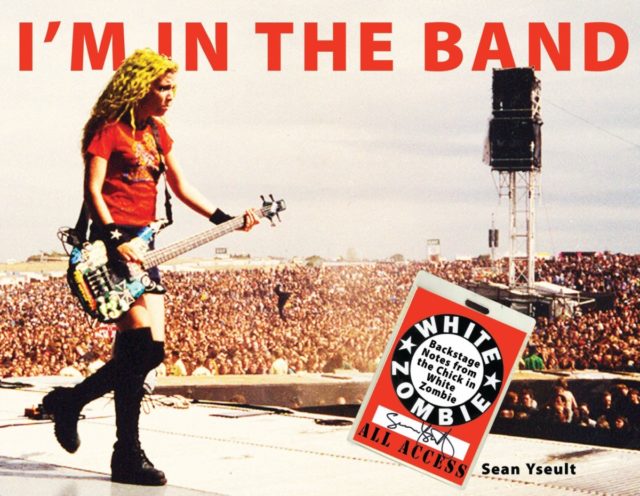

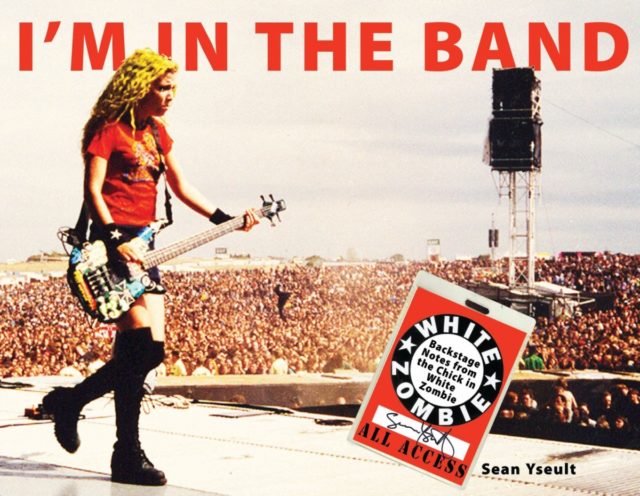

The best part was her: Sean Yseult, the tiny woman with the glorious head of hair, killing it on the bass guitar without once looking self-conscious or worried. She was laser-focused on her music, far too cool to bother gazing into the camera, and she head-banged her torrent of curls so surely it all took on a brutal elegance. If I tried it I’d have chipped a tooth. I admired her, the way she played, yes, but mainly her sheer presence, the ability to be there, so confident, among all those guys, making those strange, wonderful, angry sounds like it was no big deal. It took a few watches, but I eventually came to appreciate the entire band’s touch of camp, the sly humor, the nod at old horror movies. In the video for “More Human than Human,” the single that won them a Grammy, a fifties-era robot boogies while an evil Abe Lincoln menaces the camera.

It was a driving sound, something that got under your skin and stayed there, secret and rebellious. However, my affection was less for the band’s music than Sean Yseult, girl in a musical maelstrom. She inspired me. Suddenly being a dependable, unremarkable girl wasn’t enough, and it definitely wasn’t cool.

Artist and musician, Sean may be best known for cofounding White Zombie, the art/punk band that later developed into a signature metal sound. After a decade of struggling, the band went multiplatinum, earning a Grammy and touring with bands like The Cramps, The Ramones, Pantera, and uncountable others. She was one of the first female musicians in heavy metal at a time when even the fans were 99.9 per cent male. Yet her upbringing is not so “hardcore”: it was one of fine arts, literature, dinner party discussions and dance. Her parents were English professors, her mother a scholar of Chaucer and her father a National Book Award winner and author of five Hemingway biographies. Today, nearly two decades after White Zombie’s breakup, Sean has gone back to what she started out doing: making art and designing. (She’s still making music, too.) Sean was kind enough to let me interview her not once but twice, first in New York and again in New Orleans, about art, music, and life then and now, her latest exhibition, and why she never liked the constant questions about being “the only girl” in metal.

—Leia Menlove for Guernica

The New York City Interview: Where White Zombie Was Born

My first interview with Sean took place in her Bowery apartment, overlooking the increasingly fashionable neighborhood that, in the eighties, had been crime-ridden and filthy. She hasn’t changed that much since I saw her on MTV: the hot pants and cropped leather vest have given way to trousers and a vintage-chic blouse, but the cascading blonde hair and the doll’s eyes, the calm presence that struck me as a teen, are still here. As we stood at the window, Sean recalled the New York City of the ’80s, the rats and drunks, the threat of muggings, the shows they played at CBGBs, the heady days of musical experimentation, of developing a new sound in artistic company with bands like The Cramps and The Swans.

I remember sitting there in a bar in Raleigh, eight years old, playing improv piano with these old blues men, smoke everywhere.

While the story is endlessly fascinating, I was there to talk about more than the band, and zero in on the woman. Thankfully, the White Zombie saga has been told, and told well, online as well as in Sean’s 2010 book I’m in the Band. A recent box set release of by Numero Group has also prompted some fantastic articles, including stories about their early days.

I wanted to go back to the beginning. How does the gifted daughter of a National Book Award Finalist father and a Chaucerian scholar mother came to play heavy metal, a music regarded by some, especially then, as transgressive, offensive, or as, simply, noise?

It started with the blues.

“I have this memory,” Sean said. “I remember sitting there in a bar in Raleigh, eight years old, playing improv piano with these old blues men, smoke everywhere. One guy was playing the brushes on the drums, another was on a stand up bass. My teacher taught us how to do improvisation in these rooms full of uprights and electric pianos, three days a week. She’d play something in C Minor, say, and then point to you. You were supposed to improv based on what she’d done. Then she’d point at someone else and it would be their turn. It was great. We lived in this weird little pocket of North Carolina, the research triangle, very academic, very supportive of the arts.”

By twelve, Sean had joined a band and toured briefly around the state. “My first tour was way before White Zombie,” she laughs. Also a dedicated ballet dancer, Sean found the competitive and vanity-riddled world ultimately didn’t suit her. “I just didn’t have that thing where you want to stare at yourself all day in the mirror,” she said. When she broke her foot, Sean enrolled in art school and found her niche.

“I was an outcast when I was a kid. A freak. My hair didn’t grow right. I was rail thin. I’d try but no one wanted to be friends with me until I went to art school where everyone was like me, a freak. That was great.”

Later Sean attended Parson’s School of Design in New York, where she met the man who would become Rob Zombie. “We were the only two freaks in the cafeteria!” (She explains that for her, the word “freak” is the highest compliment.) “Who wants to be normal?” Sean and Rob soon became inseparable and formed their band.

In I’m in the Band (Soft Skull Press), Sean writes that White Zombie was never about becoming a commercial success, but about making something different, artistic. “This is difficult to convey in today’s society obsessed with wealth and fame. But the cool factor of having a band back then was that we were actually doing it—making music, making flyers, playing shows, creating a scene.”

“We were headlining a 10,000-seater and some old man stopped me from getting backstage, and I could hear my intro music going. I was like, ‘Well, I guess the show’s not going to happen.’

While White Zombie was ensconced in the New York City punk and art scenes in the late eighties and early nineties, Sean encountered a plethora of talented female musicians. But when White Zombie crossed over into metal, all that ended. In I’m in the Band Sean writes: “As a musician, I was headed into uncharted territory, hoping to sneak by before anyone noticed. Once I had, I was not only accepted into this club, but fans accepted me on a level reserved for their favorite band members and bands gave me respect as a musician, songwriter, and performer. I felt extremely lucky and thankful to have bypassed the sexism that was still prevalent at the time and place.”

Nevertheless, a handful of times, the scarcity of women in heavy metal was driven home. “We were headlining a 10,000-seater and some old man stopped me from getting backstage, and I could hear my intro music going. I was like, ‘Well, I guess the show’s not going to happen,’ but then the stage manager came looking for me.”

So how did it feel to be the only girl? Was she proud?

“I just wanted to be accepted as a musician and songwriter, first and foremost,” she said.

I pressed her: Now, with distance, didn’t she believe she was a force of progress for women who wanted to break into traditionally male-dominated spheres? Sean shrugged, less modest and more unconvinced. “I don’t feel like that. In a way I feel like I passed, you know? In early White Zombie days people thought we were four guys. We all had long hair and were really skinny and androgynous.”

Sean isn’t sure why sometimes she was perceived as a man and sometimes as a woman. Perhaps it was that some audiences, and some humans in general, only see what they expect to see, what they want to see, or what they need to see. I asked whether she had any female idols. “Poison Ivy from The Cramps, and Joan Jett. I identified with Joan Jett because she looked like Deedee Ramone, just kind of blending in, not making an issue of being a girl.”

The New Orleans Interview: Sean Yseult the Artist

“I remember going out to the outer banks in North Carolina with my father. We were on the beach and he pointed out an entire rabbit skeleton. It had lost its fur and flesh but the skeleton was just sitting there, perfect, and we stood there and admired it.”

It’s sunset in New Orleans and we’re seated and chatting in Sean’s stately, colonnaded home in the Lower Garden District. Like her beloved New Orleans, where she settled in the late nineties, Sean’s home is awash in history: faded photographs, human skulls, taxidermy, an upright windowed-coffin in the high-ceilinged dining room. There’s a sense of something leaving a room just as you enter, spirits, maybe. People have told Sean she’s morbid for her collection, but she disagrees. “Bones aren’t something morbid to me. It’s all that’s left in the end.”

She does not collect these things, nor photograph them simply because they are dead and bygone, but because she has a fascination, a connection, with the past. “I often feel like I’m from another era.”

They’d stage crazy things, dark things—images from Dante’s Inferno, mythology, the bible. I created my own plausible secret society.

I wonder if such objects and images reflect an urge to freeze time, and thereby return to experience an earlier period. The decay visible in Sean’s photographs of crumbling houses and flooded graveyards seems like a nod of appreciation at time itself and its inevitable effect on beauty. From her early polaroid portraits to the bottled women afloat in her Mississippi Mermaids series, to a cabaret dancer in Sex&Death&Rock&Roll, pausing on a moldering stair to glance over her shoulder, Sean’s work is eloquent about the fraying present: Beauty is amplified by the depredations of time, decay ennobles what it touches.

Viewers often mistook Sean’s early Polaroid portraits as legitimate antique photographs, a fact she enjoys, inspired as she is by EJ Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits and the macabre and distressed images of Joel-Peter Witkin.

“Somehow by the fifth or sixth shot on my Polaroid camera, something magical would happen. It would look like a photo from a hundred years ago. That was inspiring, the look of that film.” At one exhibition, a friend overheard an old woman who recognized herself in one of Sean’s photos. “That’s me when I was a girl,” she said. Sean was thrilled to hear this. “If you see her again,” she told her friend, “Tell her I’ll back that up!”

For her most recent collection, Soiree D’Evolution, Sean was seduced by the scraps of history she found about the long-dead secret societies of New Orleans.

“They’d stage crazy things, dark things—images from Dante’s Inferno, mythology, the bible. I created my own plausible secret society. My research took me down the rabbit hole. I’d discover something and think: ‘I really should not be knowing this,’ and delete the browsing history from my computer.”

I ask Sean whether she has ever experienced “The Birdman” effect for her fine art. She shakes her head.

“I definitely haven’t felt any hate. It’s been really great so far. When I show in New York and Los Angeles, I do tend to show at galleries who have a lot of musicians. Yet I’m lucky to have these offers of showings, so it’s been only helpful. I’m happy with anywhere that wants to show the work.”

Sean Yseult’s show Soiree D’Evolution is on display at Lethal Amounts Gallery in Los Angeles through June. Her work can be seen currently at Red Truck Gallery in New Orleans, The Studio of Art in East Hampton, and at ArtHamptons (June 23-26). Sean’s design work of scarves and soon textiles and wallpaper, can be seen at yseultdesigns.com.

Now Sean is not only making art but curating art shows. Her next project will be for Heron Arts in San Francisco this fall. The show will feature work by Moby, Greg Dulli of Afghan Whigs, Pat Sansone of Wilco, Dave Catching of Eagles of Death Metal, piano legend Henry Butler, and Sean herself. The exhibition opens September 10, 2016. Colin Day of the acclaimed “Saving Banksy” documentary will be making a short film based on the show and its curation.

In 2013, Sean’s blues-rock/metal band Star and Dagger, founded with Marcy von Hesseling and Dava She Wolf, released their first album. Watching their videos, you can see the glee in their own musicianship. They are at ease in the world they’ve made for themselves, stomping over all the rules about how a female should behave. They can play what they want, as loud as they want to, and no one can prevent them from taking the stage.