Beth fucks the exterminator while her son’s in New Jersey. It is the fourth time he’s come, jeans slipping off the hooks of his sunken hips, wielding his nozzle. For all Beth knows, the can is a prop, filled with nothing but water, but for the smell: birch beer, sweet as a soda float. She pays him, then overpays him, tipping 35 percent because she’s at his mercy and the flies keep on coming. He warned her there’d be no easy fix. They are tenacious mothers. He comes back the next day, and two days after that, hands her his card. Animal & Pest. “Buzz me anytime.” He picks his face. He takes her money. He calls her “lady,” and it’s marginally deferential. There’s a name embroidered on his shirt, but he does not look like an Ernest, and she does not ask.

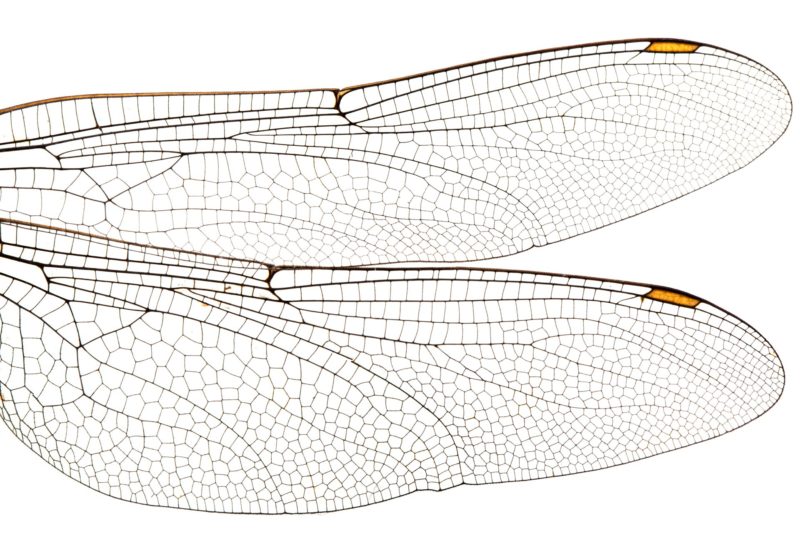

Sometimes he takes hours. She sits on the step and waits, anxiety flapping its wing across her breastbone, but no one hears her. No one sees her tears.

The exterminator is erratic, but ultimately, he shows, with his oiler and faraway eyes, administering squirts beneath the kitchen sink, lowly puffs along the caulking in the connected bathroom. At first, Beth cupped Zach’s mouth and nose, his breath misting her palm. Anything could set off an attack. Then she dropped Zach off with his dad.

From there, she tucked herself into a diner to binge on gluten and dairy. She’d forgotten how hungry she was, forking through the vinegary dish of pickles, waiting on her milk and pie. When she was a child, her mother would sometimes take them to diners as a break from cooking. A kids’ menu named after zoo animals: Elephant was a flatiron steak, bloody and pink. Chicken Parm, the giraffe; the rooster, a BLT. She devoured grilled cheese the size of her face, thick slice of tomato, seeds streaming down her wrist. In high school, she’d stab cigarette butts into puddles of condiments, bring the lit ends down on her wrists. She was sorry for so many things.

By the third visit, she stepped aside. The exterminator’s boots scuffed the floor. He left his paperwork in the truck along with a girl, sunglasses, feet on the dash, his sister, maybe, his girlfriend, his wife. Beth wondered if they’d make babies with extra fingers or stubby limbs on account of all the chemical exposure.

Reasonably priced, compared to the city’s Cockroach Coaches and Lice-No-More Ladies (now those were ladies) who combed through Zach’s curls, the exterminator is her saving grace. He is maybe twenty-five. She dials, he comes. He listens, unlike Ira, Ira Lecher, who let loose and pissed on her floor, so she gives him extra in cash, then pulls him toward the bed.

“Lady,” he says, backing up.

The exterminator is so hick it’s almost a deal breaker, but he’s young, she’s drunk, there

is a dimple in his chin like Prince Charming, the whole scene straight out of “Uptown Girl,”

with her playing Christie Brinkley to his Billy Joel. She grew up on MTV, so it takes

little convincing.

“Should I get the door?”

A ridiculous request — she’s never been more alone — though his politeness charms her. He must have a mother who raised him right. She barely steps out of her shorts before he’s gap-toothed and grinning.

“What?”

“Only I’ve never seen a hedge trimmed quite like it.”

“A landing strip.”

“Never seen one of those neither.”

She looks down. What she sees is her birth scar, a crooked ridge.

“Well, now you have.”

If she is assertive, he needs it. This is no time to be coy. In dreams, Beth is visited by that dead woman, bloated in white, an ultra-Orthodox Ophelia. Beth sifts through boxes, in dreams, packing and unpacking what belongs to her, what never was hers to begin with.

A tower arises in dreams. Ira’s face in joker paint beams from atop a milk crate. She grips

the edges of his flesh and lifts, rubbery cheeks and cleft chin, only behind his face lies a stack of other faces: Beth secures every mask. Her own reflection stares up at her from inside the box.

But this is no dream. The exterminator smells like a fist of change left in her pocket for too long. He keeps his boots on, long sleeves. She opens his belt, cracked leather. He is mealy and sour. She breathes through her nose, guiding his hand to thumb around inside her until she is ready.

Only he’s not. He’s nowhere close. She gives him a moment, pretends not to notice, but it’s like coaxing a kitten down from a tree; he’s stuck, frightened, her luck, surely this is a referendum on her, so she gets on all fours and starts rocking, cajoling, almost begging, Come on, Ernest, you can do it, thattaboy, pony up and stick it in. She feels predatory, like a man, like a creep. You know you want it, she says, but she doesn’t know anything, not a damn thing, every inkling collapsing onto itself, like the frame of a burning building, she is on fire, dying to be consumed, but for those children in Plexiglas looped to this guy’s belt, matching reindeer sweaters, fake snow, the kind of thing done at the mall, are they his kids or siblings, nieces and nephews? My God, how sweet. His keychain swings.

Head to the wall. Now that’s more like it. He thumps halfheartedly. She shuts her eyes to conjure a rhythm, and the vision of rot returns. Maggots crawl through rice, skin warps like desert clocks, a film strip clicks; she’s in health class, junior high, angel dust is not for angels. Go Ask Alice flies from locker to locker. It’s taking forever. At this rate she’ll be dead before he comes.

“Hold up,” he says, and just like that, he’s out and zipped. “Lady, you got an attic?”

She waves in the general direction. While she collects herself — Did he even finish? — he snaps on blue gloves like the kind Zach’s camp counselors wear on bathroom duty. A few minutes later, he climbs down from the dark.

“Found your problem!” he says, jangling a rusted cage.

Bit of bird, mange of squirrel, possibly a rabbit, all but ossified. He’s found nothing. The trap is old. The exterminator did not set it, but Beth plays along. My hero, she says, going to him fresh. He peels her from his tattooed neck. Lady. Light’s splinting through the rafters. Might want to see to those holes. Cracks can be systemic in a house this old. He knows a guy for that, but she says, No need, thank you, we’re only renting.

Excerpted from LECH, copyright 2022 by Sara Lippmann, forthcoming from Tortoise Books in September.