The internet smells. It smells like mildew and eucalyptus trees, like hot asphalt and sea air. The internet is noisy. It sounds like the drone of an industrial swamp cooler and the hum of an electrical current. The internet tastes like a cup of peanut butter pudding and it looks like a star chart.

In his new book Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet (Ecco), Andrew Blum, a correspondent for WIRED and contributing editor for Metropolis, examines the physical infrastructure of the internet; from the miles of fiber optic cables beneath the oceans and the enormous data centers of Google and Facebook to the university classroom where it all began, inside a refrigerator-sized metal machine. This is a voyage to understand the internet by charting its physical geography. The result is a zippy history of a phenomenon that, as a society, captivates us, connects us, and vexes us. If we are rapidly becoming a digital world, Blum asks, what is that digital world made of? Beyond the narrow scope of a computer screen, what is the tangible landscape of the often intangible experience that is the internet?

How secure is our privacy when our information is shot around the world on a trellis of cables, routers, and wire?

Tubes is not a meditation on our psychic experience of the online world—it does not wonder whether Facebook is making us lonely, turning our children into cyber bullies, or fomenting the roots of the next Arab Spring. Blum appropriately takes for granted that the reader is aware of these quandaries, and has almost certainly had their own moments of spiritual ennui as a result of a late night Youtube binge. Rather, Blum’s aim is to take the internet apart and put it back together again, to lift the hood of the car and show how the great engine is powered. Tubes attempts to bring the internet down to size by breaking down a concept so often associated with abstract descriptors (the cloud, cyberspace, the world-wide-web). In describing transatlantic cables that connect continents, Blum explains, “The fiber-optic technology is fantastically complex and dependent on the latest materials and computer technology. Yet the basic principle of the cables is shockingly simple: light goes in on one shore of the ocean and comes out on the other.”

Blum clearly delights in the technology that powers the internet, and spends chapters breathlessly recounting the first network connections or marveling at the “ultimate enjoining of the of the unfathomable mysteries of the digital world with the even more unfathomable mysteries of the oceans.” But at its heart the book is a kind of travelogue of the weird and wonderful people and places that make the internet run. We follow Blum deep beneath New York City’s busiest avenues and to the edges of England’s rocky coast, all along encountering characters and vistas that would not be out of place in an adventure novel. In the most interesting and absurd of these escapades, Blum is taken on an elaborate tour of Google’s data center in Oregon, where he is allowed to see only the parking lots and cafeteria. While dining on organic salmon and that peanut butter pudding, he expresses his disappointment at not really having seen any of the infrastructure. But, as his handler cheerfully informs him, “Senators and governors have been disappointed, too!”

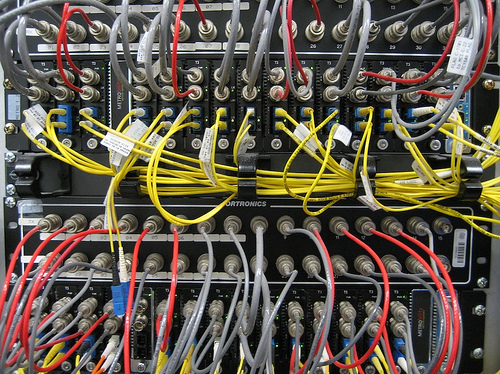

It is in this anecdotal way that Tubes touches on some of the important issues of the digital conversation. It is an interesting tact to take: remove the internet from the world of abstraction and place it firmly in the realm of the “real.” But in picturing the physicality of this network, the reader is left to ponder familiar philosophical questions. How secure is our privacy when our information is shot around the world on a trellis of cables, routers, and wire? How much of our inner lives have we given over to this medium of light and electricity? Blum’s take is cleverly subversive if not ultimately enlightening. In mapping out the hubs and routes on which the internet functions, he leaves the reader to reconcile the very real and physical existence of the internet with our highly complicated and ephemeral digital constructions of self.