The Mastermind y lo contrario

2014

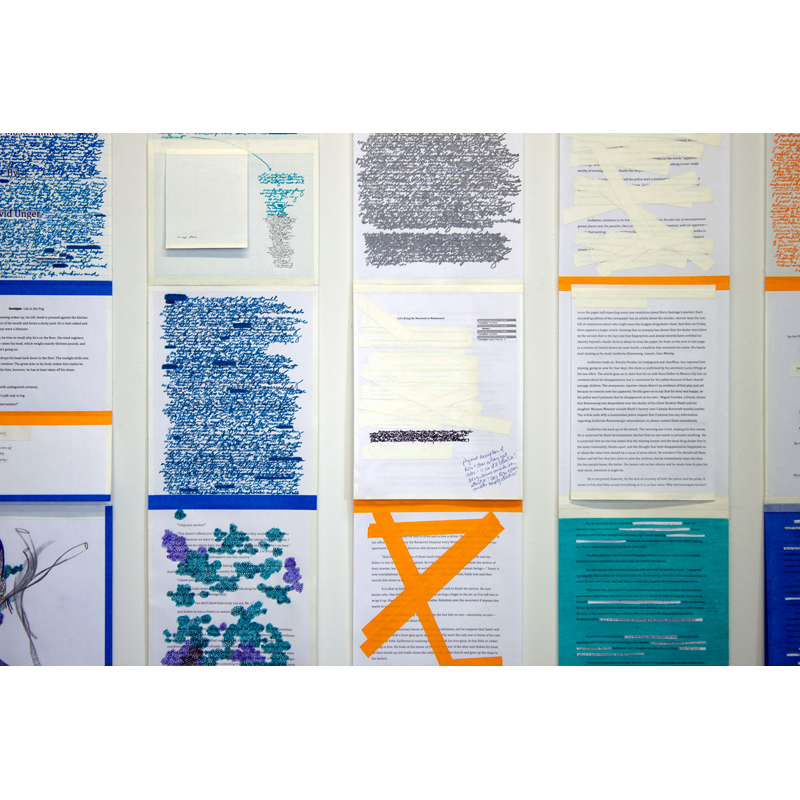

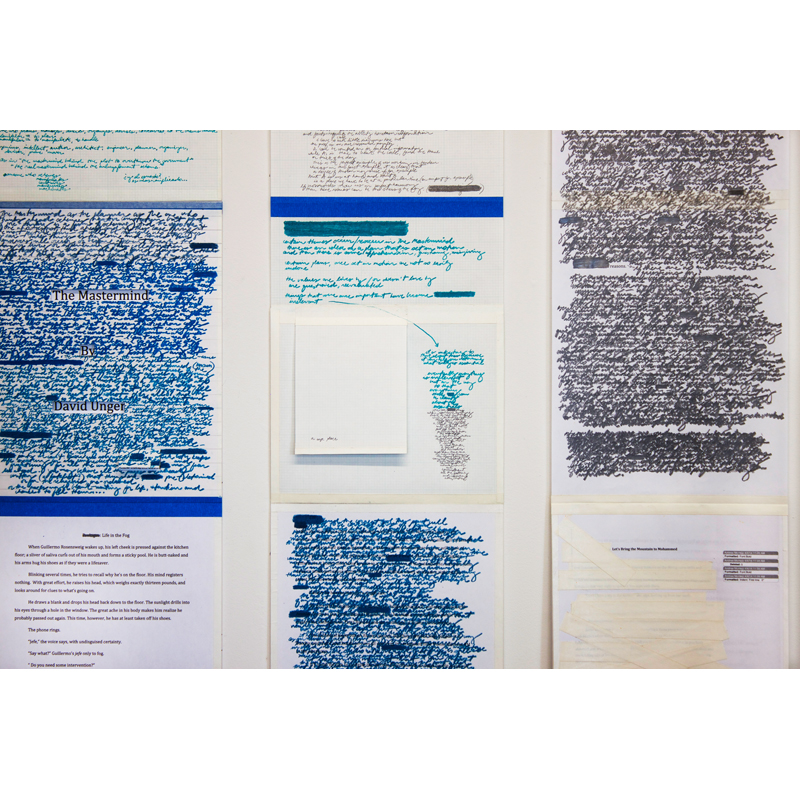

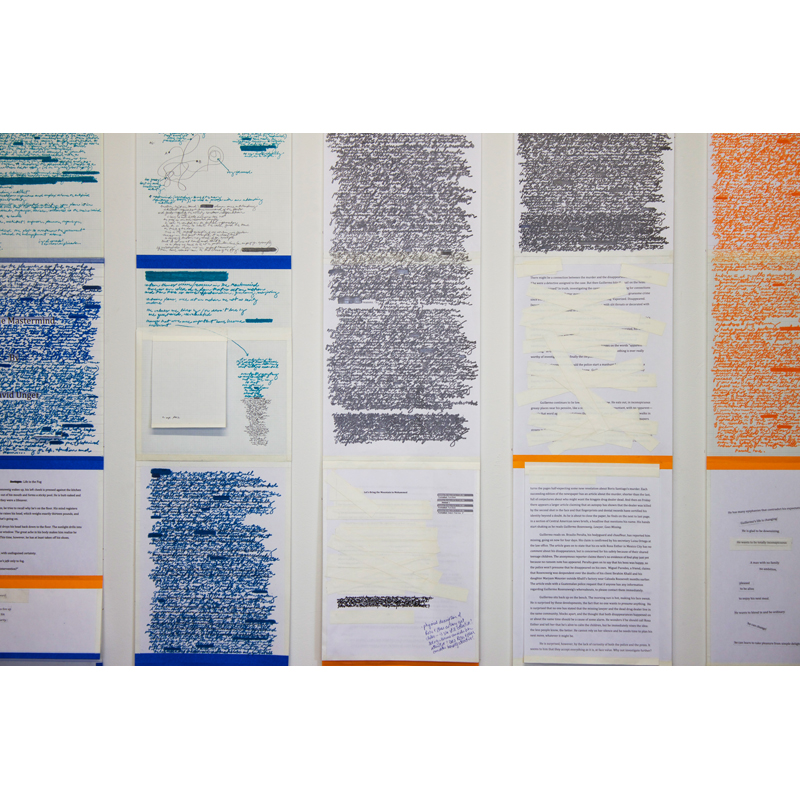

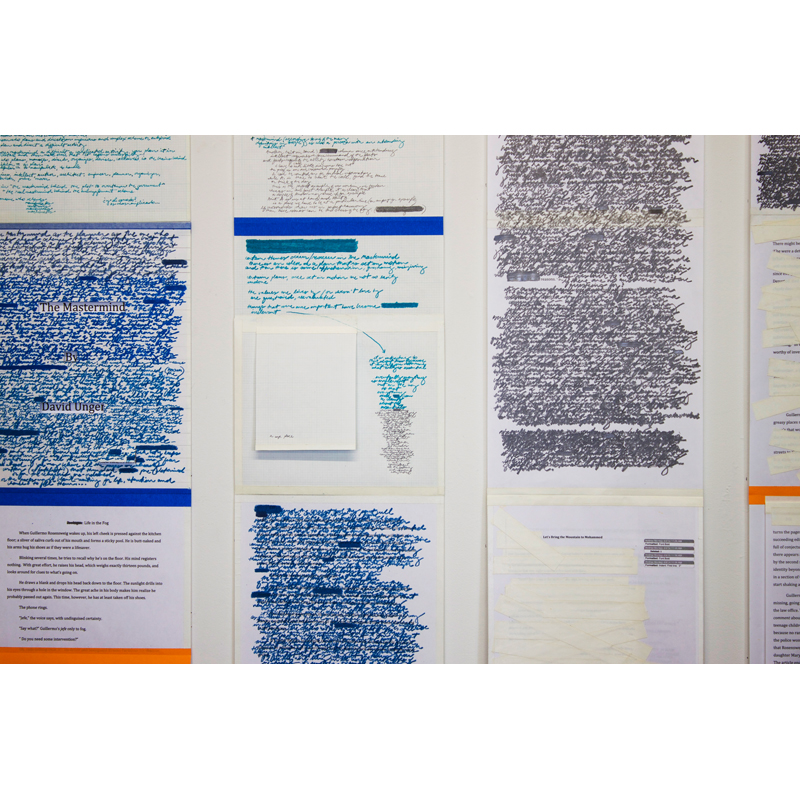

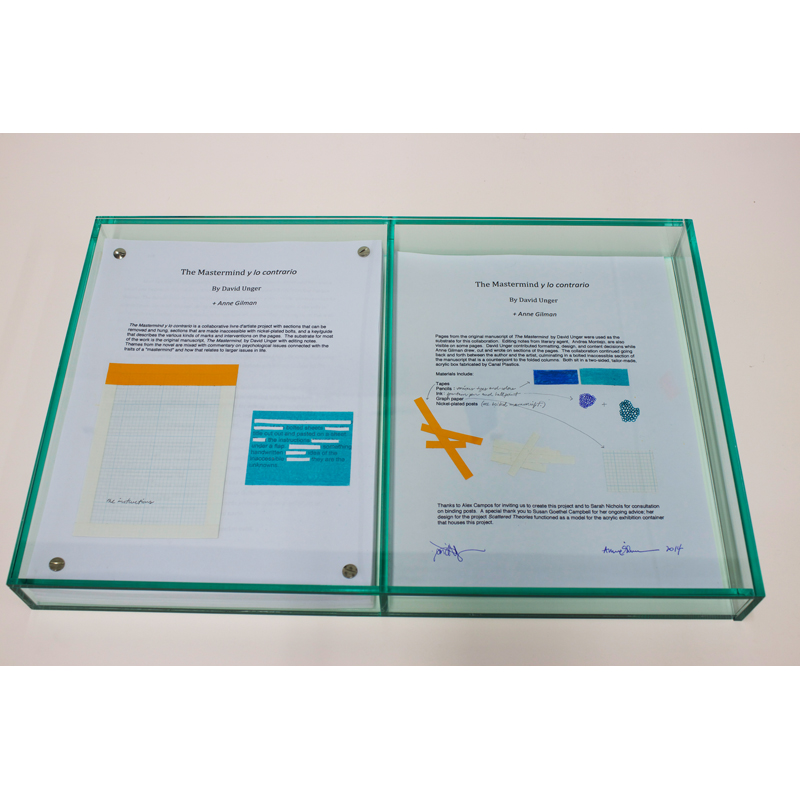

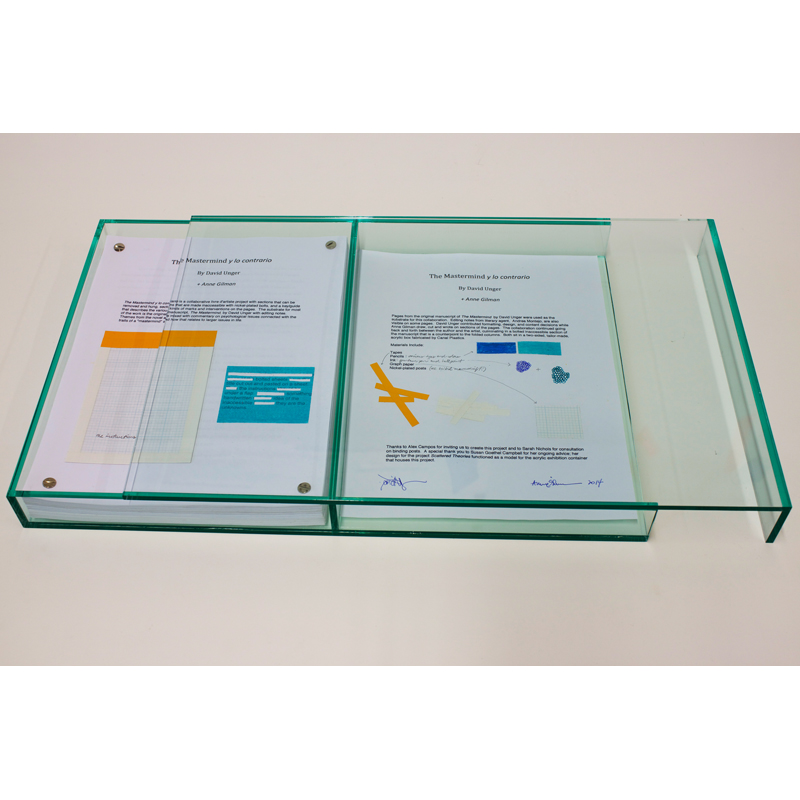

pencil, ink, tape, nickel-plated bolts, acrylic tray Installed: 56" x 70" + pedestal for acrylic tray

“The Mastermind y lo contrario” is a collaborative art piece by novelist David Unger and visual artist Anne Gilman currently installed at the group show Livre d’Artiste d’Aujourd’hui: Interdisciplinary Collaborations at the Center for Book Arts in Manhattan. Traditionally, a livre d’artiste, or “artist’s book,” is an artwork produced in the form of a publication. Alexander Campos, the Center’s executive director and curator, put together, with Maddy Rosenberg, curator at CENTRAL BOOKING, the exhibition, which considers the livre d’artiste as a joint creative venture between different types of artists: writers, poets, translators, musicians, painters, illustrators, glass blowers, videographers, and designers. “The Mastermind y lo contrario” is a visualized version of Unger’s novel, through Gilman’s eyes.

Unger and Gilman live together in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Unger was born in Guatemala and spent his first five years there, and visits annually. His insight into life in Guatemala is a large part of his work: all of his books were published in Latin America, among them, Life in the Damn Tropics (2004) and The Price of Escape (2011). Many sensory and geographical elements filter through The Mastermind, his fifth book (as yet unpublished), a political thriller. The story is fictional, but is based on a real event in 2009 that shook Guatemala: the murder of Rodrigo Rosenberg, a corporate attorney who allegedly orchestrated his own assassination.

After his death, a video of Rosenberg speaking alone was released. In it, he declared to the camera: “My name is Rodrigo Rosenberg Marzano and, alas, if you are hearing or seeing this message it means that I’ve been murdered by President Álvaro Colom, with the help of Gustavo Alejos.” This threw the country into a constitutional crisis, unraveling stories of corruption, betrayal, love affairs, and conspiracies that are still playing out. Initially, the president was asked to resign. “The president gets on TV, and he’s there with two handkerchiefs, trying to mop the sweat on his face,” says Unger. “He looks totally guilty. We learn a year later that he had nothing to do with this event. People all over the world [were saying] that reality is stranger than fiction. One of the premises for my writing my novel was to say, no, actually, fiction is stranger than reality.”

Gilman’s work spans installation, print-making, mark-making, drawing, artist books, and multi-panel projects. She works often with text, focusing on the nature of interpretation and translation by incorporating her own direct emotional responses. She has exhibited worldwide, with fellowships from the Edward Albee Foundation (2010) and MacDowell (2011). She is currently working on “Black and Blue,” a ten-panel piece related to a previous project, from 2013, called “Loss of Language.” She is also continuing a series of collage drawings that have a relief element, where the work is built up above the surface.

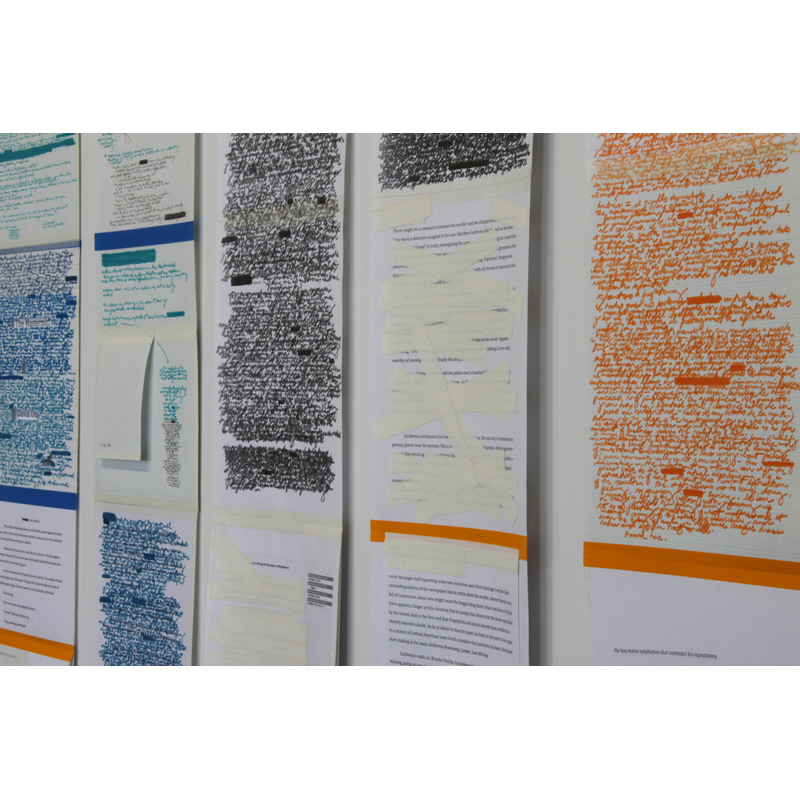

Gilman selected and altered pages of The Mastermind that interested her, without regard for chronological narrative. Mounted on a wall, “The Mastermind y lo contrario” consists of six different sections, each section comprising five pages from the manuscript, which invite interaction: parts can be manually removed, lifted; others are inaccessible due to the application of bolts. Gilman annotated, blocked, cut out, and illustrated the text, and provided a key detailing of her intentions. She focuses on the psychological, more subjective themes that arise.

Livre d’Artiste d’Aujourd’hui: Interdisciplinary Collaborations exhibits in Manhattan through September 27th and opens at MDC Galleries of Art + Design (Miami) in November. I spoke with Unger and Gilman about their work in early August.

—Alex Zafiris for Guernica

Guernica: How did this collaboration begin?

David Unger: I wrote the novel, and then Anne riffed on the manuscript. We talked a little bit about process. As an example: if you look at the piece, it is made up of six scrolls, six different sections. The pages are not in any chronological order. That was one of the first decisions. There is one section of the work that deals with the definition of the term “mastermind,” and also how I tend to write, and how Anne creates art. The decision was informed by the fact that Anne doesn’t work in a strict chronological order.

What I wanted to do was not give away the story. I wanted to entice.

Anne Gilman: When I work, I do not go from point A to point B, in a straight line. It just doesn’t seem possible. I start off going someplace in the work, I’ll have another idea, and I’m off on something else. Eventually I get to point B, but it’s a very circuitous route. That’s part of what David is referring to: let’s play with this idea of not going in order. I don’t always know why I do what I’m doing, but I have a very clear need to do it a specific way. With almost everything in my work, I could tell you why I do it after the fact. Except for color choices. I don’t ever fully understand why I make them, but I know they’re essential. I can look and I’ll go: “I need a really bright blue.” I couldn’t tell you why I needed that bright blue.

Guernica: How did you choose the pages?

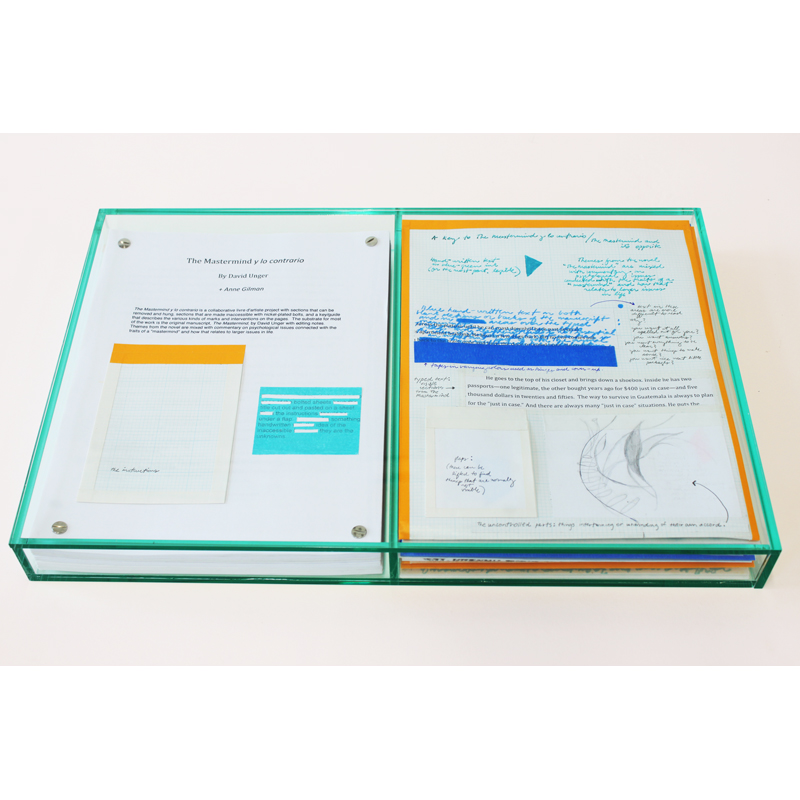

Anne Gilman: What I wanted to do was not give away the story. I wanted to entice. In my work in general, there’s always a lot of writing, editing, or redacting; certain things are less visible or legible. They act as keywords to give an idea of what the work is about. In this case, I decided that I wanted to leave specific passages that would be suggestive of what was going on, and relate to themes that I am very interested in. The themes in David’s novel really address the big issues in life: loss, lack of control, unexpected occurrences, thinking you know something and then finding out maybe you don’t. The unexpected, the lack of predictability. I think one of the biggest challenges most of us face is when we are whammed by something. It throws everything in life into flux. There’s also love in the novel, and politics. There’s a lot going on, but I veered in on the things that showed introspection and questioning.

David Unger: Anne made visible a lot of very choice phrases that relate to the issue of the ongoing mystery in the novel, and some of the sexual tension, not so much concentrating on the Guatemalan background. The title of the piece, “The Mastermind y lo contrario,” is in literal translation “The Mastermind and Its Opposite,” but the meaning hints at the idea of someone who wants to control a situation, and the fact that we are powerless to control things in life. Once we understand that we can’t, we’re probably better off.

Anne Gilman: This project related to an earlier one, “The Jolly Balance” (2008-9). About five years ago, I had an original handwritten text from 1918, a science journal. I did a similar thing, where I took the idea of experiments that are all about control and control groups. I redacted anything except the parts that went to things that are out of control. I used it as a way to consider a more human experience, as opposed to what I think a lot of us desire: the feeling that you’re not at the mercy of whichever way the winds blow, that you have some sort of impact on how your life unfolds.

Anne’s work has actual physical layers where things are hidden. You can open up a flap, or pick up the whole page and see something behind it.

David Unger: What I really like about the scroll pieces is the idea of these different layers. The last ninety pages of my novel become more of a mystery as to what actually happened. I play with this historical event, and completely change it. Anne’s work has actual physical layers where things are hidden. You can open up a flap, or pick up the whole page and see something behind it. Even looking at the piece, you can see that there are words that come to the surface from a page behind. To me, this relates very much to the issues of what is the reality, what actually happened, and what is the real truth behind the events that I describe in the novel.

Anne Gilman: What you can see, or not ever really see.

David Unger: Something that influenced my concept of my book is a mural painting by Diego Rivera that is in the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. It is called “Man, Controller of the Universe” (1934). It has a man in the center of this huge mural, with all these levers, a microscope, a telescope, and all around are different scenes from the history of the world. Trotsky is there, Lenin is there. At the center is this guy trying to control the world, which of course is not a possibility.

Guernica: Did this project open up any new thought processes or methods?

Anne Gilman: David had an effect on formal decisions. It wasn’t just that he did the manuscript and then I did the artwork; there was a real give and take. At one point I said, “You know, David, since I’m not drawing on every single page in the manuscript, I want a chunk of it to be inaccessible. I’m trying to figure out how to do that. I could tape it up, but that seems sort of messy, I want something very clean…” And David said to me: “What about bolts?” I thought, Oh my god, how perfect. I researched and found the nickel-plated posts, and the rest of the manuscript is bolted together. For me, that’s what you can call the end of the story, or the part we don’t know yet, if you’ve not finished it, or the unknown in life, if you will.

On the last page, on the last column, at the very bottom, is the last piece I did. It is a page that David wrote, and over it is a vellum—which is a translucent page—of my handwriting filled with text. Those two are attached, so that you can’t access what is underneath. That was an important part for me.

David Unger: I love all the cutting out. There are a number of different pages where Anne has further edited or redacted the type-written page with a light blue and dark blue. I like that there are different kinds of surfaces, and that it is not just Anne’s writing; there are images of nature, and obsessive little circles, which is an important part of her work in general.

Being married for fifteen years, there’s an understanding of what she’s going to react to, and what she’s not going to like that much.

Guernica: Tell me about the installation of the piece.

Anne Gilman: There are six panels which come directly from the novel, and there’s a shorter piece with orange around it. That’s what I call the key to the piece, or the guide. I’ve never done that before. It explains every single way that I have interacted with the novel. There’s an explanation for each section, but as a friend pointed out, it’s also in my handwriting, so it’s also not as accessible as a key might normally be! That’s one of the things that this project got me thinking about: Do I want to actually provide a key, a title page, or colophon that you can see in a tray, a type-written part that is extremely clear, and not forfeit the drawing parts that have text, but still offer some sort of clarity, should someone be interested?

David Unger: I admire the work that Anne does. Being married for fifteen years, there’s an understanding of what she’s going to react to, and what she’s not going to like that much. I enjoyed very much her page choices: I think she focused a lot on the aspects of the visible that create mystery. I never think of the work as art that should be looked at literally.

Anne Gilman: It’s nice to see people walk over to it, start to read, ask us what it is about, lift sections. It’s always fun to see people engage with the work.

David Unger: Some people feel uncomfortable confronting a work of art without really having an explanation. They are attracted by a piece, and even before they’ve taken in the totality of it, they zero in and try and read the caption. I think Anne uses text in a variety of ways, and part of it is to be read, and part of it is not to be read. There’s a lot of drawing and taping and cutting out that goes on, that in some ways is what the piece is about.

Anne Gilman: I get the idea that a work should speak for itself, and that sometimes there’s too much information, and that people focus on explanation rather than the experience. But I also feel that it can provide a context. Sometimes art is not easy to understand. Some people really do need an entrée into the work. What I find sort of funny is that in this piece I provide a key to try and understand it, and still, at the opening, people came over to me and asked me about it. I said, “Actually, there’s a key in this drawing!” But people want to hear from the artist, and that’s great. It’s good to always have that interaction with another person. It’s an opportunity for me to learn what people focus on, what they don’t, and if that affects my own thinking in the studio.

For me it was probably the most enjoyable piece I’ve done in a long time, because I was not in it alone. I mean, I can always share what I’m doing with David, and he can give me feedback, and so on, but in this case, it was really fun to be able to see what he thought about what I was doing with his work. One part that made me so happy: I cut out some phrases that I liked, and stacked them sort of in a ladder-like way. One day David came in, and he looked at me and said, “Wow, that’s like a poem!” It was very rewarding. It was just a way to have conversations about things that maybe you wouldn’t necessarily have.