The New York subway gets uncomfortable.

I have witnessed race fights, kids licking handrails, and innumerable subtle and not-so-subtle perverts. Everything occurs inches away or in your lap. This subway—the largest, most socio-economically diverse, and efficient metro system in the country—is unyielding in its rejection of distance. In contrast, the modern Los Angeles Metro Rail was built to avoid tension. It was built to make the majority of politically powerful constituents comfortable. It is filled with space. Space between riders on the moderately used Red Line or on the ghost town Gold Line. Space in the soaring major stations, beautiful in their sleek, comprehensive visual design and speckles of symbolic fine art. Compared to New York’s subway, the LA Metro Rail looks pristine. The seats have fabric; the trains do not groan and sway like a rickety small town roller coaster. I have never had to dodge a stream of urine trickling slowly down the car.

But after over forty years of construction and wrangling, is the LA Metro Rail a real system? Is it a feasible alternative to driving home from the bar? Can it get transit-dependent residents to work in an hour? For these crucial issues, it has been lip service. The reasons for this failure emanate from the Metro Rail’s origin stories. Tales of the chronically delayed Red, Purple, and Expo lines reveal the deep conceptual flaws of the city’s approach. These tales follow an aimless hand-to-mouth hero who has stumbled through an expensive collage of fits and starts, lengthy political games, and deficient funds. They tell us that LA’s residents, as much as its politicians, have created the transportation equivalent of a forty-year-old virgin.

“Anyone who wants to be mayor has got to carry the Valley,” observed former Rapid Transit District board president Marv Holen when reminiscing about the planning of the Red Line. He was speaking of that great northern suburban swath of Los Angeles county: the San Fernando Valley. The Valley is the half of LA that you peer down on when you hike the mountains of Topanga or make a doomed but inevitable attempt to touch the Hollywood sign. Its cities and residential districts like Burbank, North Hollywood, Van Nuys, and Reseda are the port of call for the fleet of red brake lights that float up the 101, the 5, and the 405 highways in the evening. With its critical portion of homeowners and voters, the Valley holds a firm sway on city and county politics.

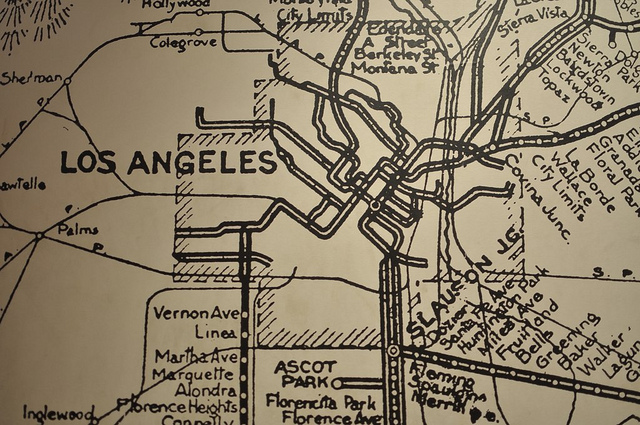

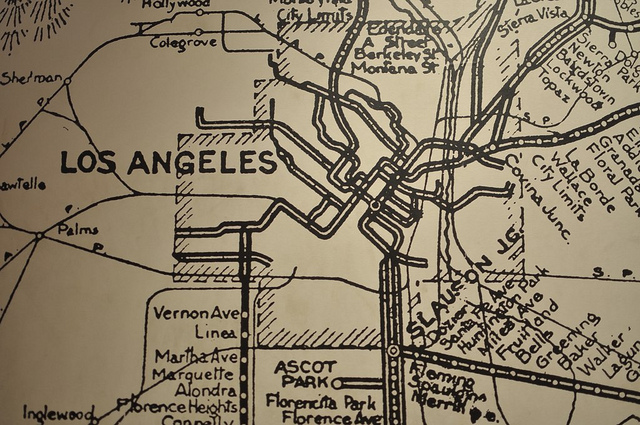

Once plans spawned for a city metro under Mayor Tom Bradley in 1973, Valley representatives relentlessly argued for their portion of the harvest. However, they resisted the noise and intrusion of cheaper aboveground light rail and instead lobbied stridently for a more costly underground subway to the Valley at the expense of denser and less politically powerful parts of the county. South Central politician and tireless Metro Rail advocate Kenneth Hahn described this style of typical county politics as involving, “the attitude of ‘my city’… and if they are not personally involved then they do not want to participate even though some of their citizens work downtown and in other parts of the county.” Worried about Valley votes for the countywide sales tax increases needed to fund the subway, Los Angeles and Metro Rail officials altered subway plans to incorporate the Valley. Getting the Valley involved meant years of horse trading that blew money, time, and energy, before compromising by building the expensive Red Line subway route in four parts, the first debuting in 1993 and the last in 2000. The line terminates at the edge of the Valley in North Hollywood, leaving the bulk of the Valley untouched, while giving its residents access to central LA.

The Red Line, however, was not built for ridership. It was built for politics.

Today, the Red Line’s ridership is sparser than the inaugural Blue Line, Bradley and Hahn’s embattled darling that opened in 1990 and cuts an aboveground path from downtown through Compton and Watts to Long Beach. On a typical Saturday, the Blue Line is the only metro line where the air gets close and the seat next to you is always occupied by another body, pressing slightly into your space. The Red Line, however, was not built for ridership. It was built for politics. The rest of LA’s Metro Rail has proliferated in this fashion, following the path of least political resistance and bloodhounding scarce funds at the local, state, and occasionally federal level.

“If Metro Rail is built, the problems that we would suffer would be tremendous,” testified Diana Plotkin, Vice President of the Beverly Wilshire Homeowners Association, in a Los Angeles Planning Commission meeting twenty years ago. She was talking about the second, and ultimately more monstrous, enfant terrible of the Metro Rail system: the Purple Line down Wilshire Boulevard. This corridor is the most densely populated in the city and so an ideal candidate for a subway. Yet during the 1980s and 1990s, this line endured staunch resistance from constituents in West Hollywood and Beverly Hills. It was a different kind of resistance than the battle mounted by the Valley.

The affluent central LA residents of West Hollywood and Beverly Hills did not angle for their portion of county funds. Instead, they fought to push city resources away from their neighborhoods and thus keep the challenges of a large city at bay as well.

Plotkin’s definition of tremendous suffering in Beverly Hills included “heavier traffic and parking shortages.” Fearful homeowners along the proposed Purple Line route worried about noise, traffic, parking, crime, property value, commuters, and visual blight—basically, the problems of any large modern city. Representatives of the Fairfax district depicted their elderly Jewish constituency as anxious that the subway would destroy and destabilize the neighborhood through gentrification. They wanted to keep younger people and commuters out; they did not want the character of the neighborhood to change.

When we think about ourselves in small pieces, we talk about reorganization rather than solutions. This is why the spatial reorganization proposed by the metro deeply alarmed many affluent residents: it threatened the containment that they had spent large sums of money to enjoy. Their protest was not that things like noise, crime, and blight existed in the city, but that those things might come to exist in their own neighborhood. Gentrification has altered the landscape of Los Angeles, turning over the character and demographics of many neighborhoods, but the residents of Fairfax put their foot down: Not In My Back Yard.

LA’s NIMBYism has led to a myopic, reactive kind of politics around the Metro Rail.

We like to believe that this kind of isolationism only existed in the most opulent neighborhoods of the past, but NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) protest politics has not been limited to the 1980s or to neighborhoods along the Purple Line. Two decades later, officials planned a parallel Expo Line running from South Central due West to Culver City, just below the I-10 highway artery. In response, affluent white homeowners in Cheviot Hills and Rancho Park protested stridently. City councilwoman Ruth Galanter inherited the constituents of Cheviot Hills as a result of redistricting, and she recalled the fears that these homeowners expressed: “I inherited all the people who were hysterical with opposition at having ‘those people’ come through their backyard. They were worried about people coming from other parts of town and coming into their house and stealing stuff.”

LA’s NIMBYism has led to a myopic, reactive kind of politics around the Metro Rail. Public support for the metro has been in constant flux, based on the state of the economy, the current fervor of environmentalism, and the unbearableness of traffic in your area. Once the will for expanding Metro Rail is amassed, it fractures under an endless argument of where the metro should not go. With unreliable general public support and pockets of fierce resistance by affluent white homeowners, residents have created a climate which encourages wary politicians to do what they do best: pork barrel, hedge, negotiate, trade, stall, and attain only piecemeal victory. As California state senator and Red Line path influencer David Roberti justified: “If your constituents don’t want thousands of commuters coming in, there’s not a politician in the world who is not going to respond to that, okay?’” U.S. Congressman Henry Waxman responded to his wealthy, largely white constituency by browbeating Purple Line plans. Alongside allies at the state and local level who represented the same constituencies, he used the threat of underground methane to generate a city task force that declared his area a high-risk zone. Using the threat of voting against federal funding, Waxman ensured that an LA subway would not cut through his constituencies in Beverly Hills, Hancock Park, and West Hollywood. During the planning of the Expo Line twenty years later, the fearful opponents of Cheviot Hills and Rancho Park similarly found attentive political ears. They managed to stall the line for a decade.

As we get into the meat of the twenty-first century, progress has begun to peek through at last. The Expo Line triumphed over protests and reached the terminus of downtown Santa Monica this year, finally connecting the center of the city to the beach. After the delays and expenditures of the Waxman era, the Purple Line is in progress, and should be completed only forty years behind schedule, if funding continues. In the meantime, LA has lacked metro service to the Westside for decades. Ironically, the crippling traffic that ensued was the main reason that Beverly Hills metro opponents finally relented.

In the midst of this momentum, the quiet outcome of a vociferous battle in Hancock Park whispers that NIMBYism is still alive and well. For decades, NIMBY residents have desired to control not only the routes of the metro lines, but also the location of individual stations. In the early 1980s, an intense conflict over the location of a planned Purple Line station erupted in one of the most untouched parts of LA.

The residents of Hancock Park enjoy stasis. The neighborhood has clear boundaries, a history of the city’s first families, high income, a large percentage of white residents, and impressive political power. In 1949, when famous singer Nat King Cole managed to become the only African American resident, the Ku Klux Klan greeted him with a burning cross on his lawn. South of Hancock Park, the demographics change markedly. Asian, African American, and Hispanic residents live in the Koreatown, Mid-Wilshire, and Mid-City neighborhoods below Hancock Park. The 1-10 freeway then cuts a forceful East-West barrier between Central LA and South Central, the historically African American part of the city that is notorious as the birthplace of the Watts riot and the gangster rap of Compton. South Central is a massive swath of the city, in which the safety and character of neighborhoods varies, but it includes many residents who are low-income and transit-dependent. The fault line between Hancock Park and these minority neighborhoods beneath it became another sparring ground. The Purple Line’s plans included a stop at Crenshaw Boulevard, a North-South artery of South Central that dead-ends at Hancock Park.

South Central commuters must continue using a maze of buses or find an extra twenty minutes to tiptoe around the boundary of Hancock Park each morning and night.

Race and class issues eventually came to a head in Hancock Park, despite white Angelenos’ tendency to avoid the topic. Crenshaw stop opponent and celebrity George Takei admitted that he heard comments from his Hancock Park neighbors that he strove to keep underground at the time: “Some of the sentiment was ‘We don’t want that kind of people who use the subway.’” Such residents went as far as threatening to sue the city over the Crenshaw stop. South Central advocates countered by arguing for the importance of the Crenshaw stop in allowing the area’s transit-dependent residents to connect with buses.

When NIMBY activists alter the placement of stations, they damage the ability of the Metro Rail to target high-impact locations and meaningfully connect with other modes of public transportation. As a result, the efficiency and viability of the entire system is threatened. Today, the brand new Purple Line has a stop on Western Avenue, just outside the eastern boundary of Hancock Park, and the next stop is currently under construction at La Brea Avenue, just outside the western boundary of Hancock Park. The stops at La Brea and Western avenues are a forty-minute walk apart. There is no Crenshaw stop between them. South Central commuters must continue using a maze of buses or find an extra twenty minutes to tiptoe around the boundary of Hancock Park each morning and night.

As Los Angeles continues to unfurl its Metro Rail and voters decide in November whether to approve a sales tax increase that will swell the county’s coffers for ambitious public transportation plans, debates over the merits of the adolescent metro trains have resurfaced. Journalists discuss luring business tourists, millennials, and auto owners to the way of the metro train. City officials talk about curing auto accident fatalities. Everyone talks about traffic. But no one talks about race and class. No one talks about the function of a giant connecting ribbon in a city that is still starkly segregated.

Los Angeles looks diverse on the Weldon Cooper Center’s color-coded, interactive racial map of the United States: yellows, blues, greens, and reds dot the urban landscape, representing different races. When you zoom in to view just the city, however, its rainbow crumbles into chunks. The rich neighborhoods of Malibu, Pacific Palisades, and Santa Monica near the ocean, Brentwood and Westwood near UCLA, and prime real estate in Bel Air, Beverly Hills, and West Hollywood form a contiguous banner of blue, the code for whites. South Central has swaths of green for blacks, surrounded by orange for Hispanics that stretches across large tracts of East, Southeast, and some of South Central LA. A vibrant red for Asians appears in concentrated communities—Koreatown, Chinatown, and several suburbs east of LA—and gives some wealthier districts a purple tinge. There are a few areas of the city where the hues get muddy, but it is easy to draw a clear serpentine curtain down central LA, starting at the foot of the Hollywood Hills near La Brea Avenue, sucking in almost to Western Avenue to accommodate ritzy Hancock Park and gentrifying parts of Hollywood, and then sliding West on Olympic Boulevard until winding South down La Cienega Boulevard to wrap up South Central behind its coil.

Angelenos’ conversations about race and class do not include race and class. Like realtors, we talk about neighborhoods and their personalities.

Angelenos’ conversations about race and class do not include race and class. Like realtors, we talk about neighborhoods and their personalities. This segmented discourse has clung to the city’s civic mind, even as the city grows and this concept becomes increasingly insufficient. As a result, we have created a metro system that ought to carry us into the future, but is instead based on the past’s neighborhoods, beholden to their personalities and power. We have created a system that is the progeny of isolated politics in a segregated city. Discriminatory housing laws and practices crafted this landscape, and the mobility of the car has done little to change it in the decades following the civil rights movement. A car is invaluable to most Angelenos for work, yet with the car payments, insurance, gas, repairs, and inevitable accident costs, ownership is unattainable for many low-income residents. They travel mostly by catching multiple buses, which crawl through traffic and make frequent stops. It takes an hour or two to get anywhere.

If Angelenos keep the metro system, its funding, and our minds small and divided, we will never succeed in uniting a city notorious for its sprawl. We need a grand, holistic vision for our metro and for our city. We need a new model, a new way of approaching the subject, a new discourse. One that belongs in the twenty-first century.

If, as USC professor Marlon G. Boarnet has pointed out, Angelenos originally built the city to suit emerging technology— “from walking to horsecar to electric streetcar to early automobile to the interstate system”— and we are now entering a second paradigm in which urban planners’ goal is to improve the mobility of residents, then we are in an exciting new era that can be driven by human ethical priorities. Just as the concept of user experience is changing marketing and computer programming, the application of this approach to the LA metro will radically change our vision. Making infrastructure and technology work for us instead of the other way around means that work can flow from our ethics about what Angelenos need and deserve. In this inherently more democratic approach based on user experience, race and class become integral factors. We slow down, and the side vision of people walking by on the street gets less blurry. Using the metro to serve transit-dependent residents becomes the most efficient approach for the city as a whole. When these residents move about the city in the most cost-effective and pleasurable way, benefits rebound in the city’s economy and in the sectors of education, health, and crime.

There will always be neighborhood communities, but they do not need to function with the territorial ideology of 20th-century gangs.

This user experience model involves a new idea of community. There will always be neighborhood communities, but they do not need to function with the territorial ideology of 20th-century gangs. Los Angeles is the second largest city in the nation, not a collection of hamlets. Our neighborhoods are pieces of a city, and the point of a city is the connection of its pieces. Not segregation. Not obliteration. Connection. New York, with all its connectivity, movement, and packed streets, has maintained neighborhood identity as concretely as, if not more than, any other city in America. Neighborhoods inevitably evolved due to economic currents and real estate markets, but connectivity did not blot out their identity. This balance of connectivity and identity, tradition and flux, is why migrants made New York the cultural capital of twentieth-century America. The new energy and creativity that arises from different molecules bumping off each other at diverse angles at weird times sometimes creates an uncomfortable subway interaction with new ethical challenges. It also attracts both art and investment.

As New York real estate skyrockets and its daring energy fades, creatives are streaming into Los Angeles. With its demographic and geographic diversity, LA is ripe for becoming a dynamic cultural capital of the twenty-first century. We just need to add connection. Cities that have not connected their diverse areas are those wasting enormous resources and restricting their energy. These limitations are a palpable current in rusting cities. No one wants to wade in stagnant backwater; all the best and brightest want to be in white water rapids. This November, as the new metro funding initiative goes to the ballot, residents will have to decide what kind of city we want to be. We will have to choose whether to move forward as a segregated or connected city. The priority that we give mobility determines our integration, our ethics, and the personality of twenty-first-century Los Angeles.