Early in Shubhangi Swarup’s novel Latitudes of Longing, an earthquake strikes the Andamans, a tiny ocean archipelago in the Bay of Bengal. In an instant, “the islands tilted by a few meters, drowning forests and farms.” But although Latitudes touches on the sliver of time immediately following disaster, Swarup is more interested in the shockwaves it sends through subsequent generations. “Children born in the aftermath would dismiss their parents’ stories and ancestral myths as tall tales born from the imagination of fools—the same fools who built a lighthouse in one and a half meters of water and went fishing on dry land,” he writes. “The gap between generations would turn into a gulf between people who inhabited different maps.”

In the midst of a pandemic, I am seismically attuned to disaster. It is liberating, even joyful, to experience the world of Latitudes of Longing, especially when that world does somersaults. I feel the way Victorians might have, reading a ship captain’s diary and imagining myself salt-stung and free. Latitudes is a reminder that the earth itself is alive, and that even in our isolation we are members of a changing world. In the timescale of this novel, bedrock moves, lighthouses unmoor, and you can feel the ground wander.

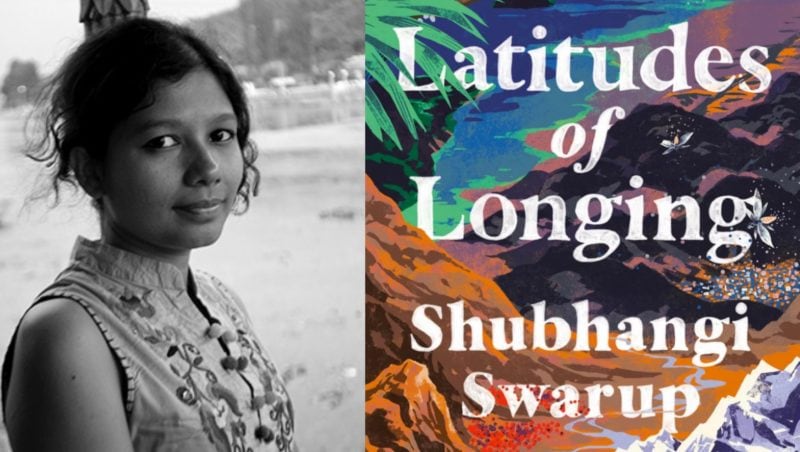

The book, originally published two years ago in India, is Swarup’s first novel. It won several prizes and became a national bestseller. It’s easy to see why: the writing is tight and clever, and the text rewards those who pay close attention to its depictions of rock and water in their many forms. “Glacial blue” eyes, verses “like mist on a winter morning,” and laughs like “pouring rain” presage plot developments like thunder foreshadows a storm. We follow a young couple: Girija Prasad, a scientist educated in the west, and his wife, Chanda Devi, a clairvoyant who speaks to the trees her husband can only study. Their journey towards love and family, in this life, is the epicenter of the novel. What follows are its aftershocks. A mother struggles to free her son, a political prisoner of the junta. A smuggler and a sex worker find each other in the Kathmandu Valley. A scientist studying Baltoro Glacier meets a lonely yeti. And an esteemed patriarch of the village One Mother, One Mule overcomes his shyness to woo a strapping visiting widow, Ghazala.

Superficially, what connects these narratives is their geography: all the stories unfold in the same subduction zone, an area of the world where continental plates cleave, shifting the earth and spurring the supernatural world to life. The earth is an active participant throughout, freeing prisoners, teaching sex ed, and punctuating chapters with earthquakes and hurricanes.

The publisher markets Latitudes of Longing as a fairy tale, and indeed, ghosts, spirits, and the supernatural abound. But with its in-depth understanding of plate tectonics, forestry, and biology, the novel also feels like science fiction. Although the two genres might first seem at odds, Swarup teases out the ways in which the supernatural hallows nature. As the scientist Girija Prasad realizes in one striking passage, “The possibility of a botanist communicating with a tree was as thrilling as the possibility of a priest chatting with god.”

Latitudes points to the limits of scientific knowledge. It is one thing to know about an ocean that once existed, but another to feel the presence of that ocean in a salt flat, the fall of rain, or the sea you swim in. Ghosts are not just human. Lost oceans, melted glaciers, and mulched trees leave traces in the earth, whose ghostly spirits make the natural world holy.

Fittingly, the novel frustrates our efforts to catalog it, even beyond the matter of genre. At times, it can be difficult to map out who exactly is related to whom, and which souls are incarnating into which people and when. Are there two revolutionary poets who ignite the world, and are ultimately tortured and forced into confinement for their words? Or are they the same person, separated only by time? Is the yeti real, or a hallucinatory snow dream? Did the turtle turn into a tree which was then fashioned into a boat, or was that merely a story the turtle’s killer told to make meaning out of the senseless? Who, exactly, is the ghost of an evaporated ocean? In an interview with the Times of India, Swarup explained that “only once you look beyond the story can you discover the architecture and patterns emerging.” But what, in a novel, is beyond the story? When you pull away from the many plot threads that make up the book, what remains?

Even geography, the most long-winded of sciences, shifts faster than one can follow. The three locations where the book takes place—the Andean Islands; the Valley of Kathmandu; and the disputed region between India, Pakistan, and China—are locations that juxtapose nationalities and identities, switching between them in the space between chapters. In this book, everything from glaciers to mangos is political.

So it is perhaps best to take Latitudes at its word, specifically one in its title: Longing. The uniting theme of the book is desire, and how fault lines separate each character from what they want. To bridge that gulf would be to destroy, for longing is what sets the world in its cacophonous, cataclysmic motion. At the close of the novel, two lovers parallel the moon and sun—and the novel itself—as they collectively struggle “to piece together an epic that sprawls across millennia, lands, and lives from the shard of a conversation.” Speaking holistically, Swarup writes, “This isn’t the first time the reluctant souls have looked at each other with longing, contemplating a free fall into the abyss. Nor is it the first time they have floundered, out of sync with the other’s steps.”

The ending of the book offers no more resolution than its start. In its stead, we are left with a glimpse of equilibrium: “the moon and the sun…exchanging glances through the snowfall, oblivious to the rest.”