If there were no Yellow Kid, there would be no yellow journalism. At least, it would go by a different name. The Kid was drawn as a bald and beaming child wearing a hand-me-down yellow nightshirt, and he was the star of one of the world’s first comic strips—Richard F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley, which debuted in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895. The cheery Kid had a habit of hanging around squalid New York neighborhoods with other rascals his age; not unrelatedly, his bald head looked as if it had been recently shaven for lice. A quick hit with readers, who were charmed by the recurring characters in their Sunday papers, the Yellow Kid was a merchandising darling. His image was used to sell New Yorkers everything from cigars to buttons to whiskey. He even came to be a spoof of himself, with his dialogue appearing on his yellow nightshirt in the weekly strips—characterizing him like a billboard.

Barely more than a year old, an emerging American art form had instantaneously become the fraught site of big business.

The Kid found his most prominent fan in William Randolph Hearst, the titan behind the New York Journal-American. He lured Outcault over to his rival paper with a much higher salary and the promise of a full-page color strip. The Yellow Kid was featured in the Journal-American’s “American Humorist” supplement, which promised readers “Eight Pages of Iridescent Polychromous Effulgence That Makes the Rainbow Look Like a Lead Pipe!” Furious, Pulitzer managed to beat Outcault out of the copyright on the Yellow Kid, and then hired another artist to continue the popular strip at the World—meaning the Yellow Kid was simultaneously appearing in two different forms in two different papers.

Barely more than a year old, an emerging American art form had instantaneously become the fraught site of big business. Of course, the Kid was just one front for the war between Pulitzer and Hearst’s newspapers—but it was prominent enough for them to soon be known as “the Yellow Kid papers.” The phrase was ultimately mangled into “yellow journalism,” and it was shorthand for how both the World and Journal-American stooped to sensational lows in their fevered pitch for turf and profits. In the end, with the Yellow Kid little more than a business battle, Hearst had no trouble letting the pioneering strip disappear in 1898, once the news rivalry had simmered down.

But some years later, Hearst came across another strip that truly captured his imagination. With this comic he cut against his usual razor instincts for business and made what appear to be irrational decisions: he spent far more money on it than even the artist—and certainly the public—thought it was worth, and he issued the artist a stunning no-strings-attached lifetime contract that guaranteed George Herriman complete creative freedom.

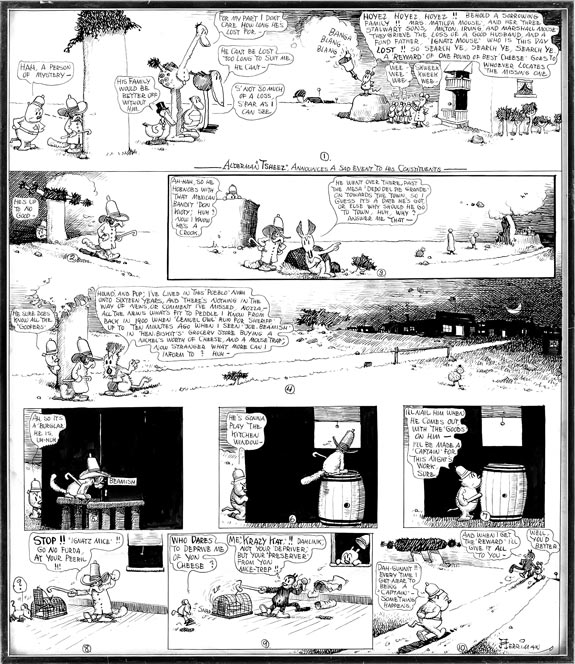

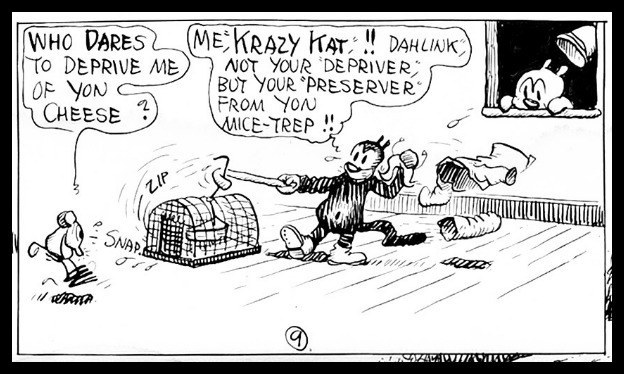

Hearst had fallen in love with Herriman’s Krazy Kat, first published one hundred years ago this month. At a glance, Krazy Kat seems like just another riff off the “funnies” formula. Its very name seems interchangeable with a thousand other strips that appeared in Hearst newspapers. Its main characters are a cat, a mouse, and a dog, and the plot is as simple as you’d expect: Krazy, a whimsical black cat, is in love with Ignatz Mouse. Ignatz (married, three sons) rejects Krazy’s devotion by throwing bricks at the Kat—which the Kat, in turn, celebrates as a sign of love (or “missils of affection” from his “li’l aingil”). Meanwhile, Offisa B. Pupp is a bulldog cop whose love of order is matched only by his love for Krazy. Alas, Krazy never suspects Offisa’s true feelings. Drawing the last line in this hapless love triangle, Offisa is always on Ignatz’s case about his habit of throwing bricks at Krazy. He often puts the mouse in jail.

That’s it. That’s the whole story.

What, then, stood out for Hearst? Why did the wealthy magnate love Krazy Kat more than The Katzenjammer Kids, Blondie, Mickey Mouse, or any other strip that he syndicated?

While the setup is not altogether different than other strips that appeared alongside Krazy Kat, Herriman’s comic transmogrified into something radical. By refusing to settle into the very formula it invites upon itself, Krazy Kat works the same way a hallucination does—or a dream, a vision. That is, in both language and pictures, it contains multiple realities at once. It is a typical playful strip featuring anthropomorphic characters and a theater of physical lunacy, and, at the same time, it is pioneering art that literally breaks outside the box with compositional innovations and astoundingly good drawing.

Jack Kerouac said the strip was a precursor to the Beat Generation, with common roots in “the glee of America, the honesty of America, its wild and self-believing individuality.”

The multiple realities of Krazy Kat are evident in the Kat itself. Krazy is Quixote-like—a fool, but valiant in his own way. An idiosyncratic knight. More pointedly, Krazy switches genders, sometimes in the span of a single strip. Krazy’s fur typically turns white when he/she is gendered female and black when he/she is gendered male; the switch is most often prompted by the social situation that Krazy is in. “I don’t know if I should take a husband or a wife,” complains Krazy in a 1915 strip. Herriman reportedly said that he didn’t know Krazy’s gender: “I fooled around with it once; began to think the Kat is a girl—even drew up some strips with her being pregnant. It wasn’t the Kat any longer, too much concerned with her own problems—like a soap opera. Know what I mean? Then I realized Krazy was something like a sprite, an elf. They have no sex. So that Kat can’t be a ‘he’ or a ‘she.’”

Despite Krazy’s gender fluidity, Ignatz’s gender stays resolutely male, bringing an unusual charge to the romantic triangle. At one point early on, Krazy creeps over to a sleeping Ignatz and kisses his forehead. Ignatz wakens and declares, “I dreamed that an angel kissed me.’” (It’s worth recalling the era: the strip debuted shortly after the Portland Vice Scandal, which implicated more than fifty men and prompted both hetero-only sex education in schools and the expansion of anti-sodomy laws.)

Press the image to enlarge.

Krazy speaks in a singular poetry as well, mashing up slang, Brooklyn Yiddish, Spanish, French, English, dialect, the alliteration of Navajo names, phoneticisms, literalized metaphors, and the onomatopoeia of comics—the zap! of the thrown brick, for example. Says Krazy at one point, “Ahwhat wundafil day-drims I’ve had today—be still my heart, flutta not so—I wunda is it ‘love.’”

George Herriman, not incidentally, spoke three languages. Oftentimes, Krazy’s corrupted language reveals more than straightforward speech would. When electricity comes to town, the Kat calls it “positivilly marvillainous.” As Elisabeth Crocker has pointed out, conflating the words “marvelous” and “villainous” reveals the twin sides of the new technology. She quotes another Krazy Kat strip that expands on the contradictory and simultaneous uses of language:

“Why is ‘lenguage’, ‘Ignatz’?” Krazy asks in a 1918 daily. “‘Language’ is, that we may understand one another,” replies Ignatz, but the dissatisfied Krazy asks whether “a Finn, or a Leplender, or a Oshkosher” can understand Ignatz and vice versa, to which Ignatz can only respond in the negative. “Then, I would say,” Krazy concludes, “lenguage is, that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.”

“We didn’t know what he was, so I named him the Greek, and he still goes by that name.”

The ambiguous reality of Krazy Kat—neither this, nor that, but both—made the strip potent enough to shape the best serial art that came after. Bill Watterson, the Calvin & Hobbes artist, broke his habitual silence to write a rare essay about the Krazy Kat in 1990, where he indicated that George Herriman’s strip was “a more subtle kind of cartooning than we have today.” Watterson went on:

“It’s wot’s behind me that I am…” says Krazy. And wot a lot there is.

The birth of George Herriman is shrouded in mystery. That is, while there is no doubt that he was born in New Orleans in 1880, his ancestry is much debated. His birth certificate lists his parents as “colored”—likely Creole. An 1880 census lists his parents as mulattos and indicates that his parents and all four grandparents were Louisiana natives. But on Herriman’s 1944 death certificate, he is listed as Caucasian and his parents are said to have been born in France. Herriman himself had light skin, though his hair was kinky—some claimed that this was the reason he was rarely photographed without his Stetson hat. And yet the artist was fairly open about the likelihood of having “Negro blood.” In the end, rather like Krazy Kat, Herriman adapted to the multiplicity of his identities. His friend Tad Dorgan, the New York Evening Journal’s sports cartoonist, wrote of Herriman’s arrival in New York, “We didn’t know what he was, so I named him the Greek, and he still goes by that name.”

As fierce as he was on the page, Herriman was unusually shy. He suffered migraines and claimed he did his best thinking while washing dishes. An animal lover, he was a vegetarian when it was hardly fashionable, especially for a young man in cowboy country. (His family moved to dusty, pre-motion picture Los Angeles when he was a child.) And yet Herriman’s precociousness ultimately made him a star of one of the earliest news syndicates, McClure’s Magazine, where in 1903 his art was featured in one of the first operations to provide rural papers with full-color comic sections. By 1906, Herriman was pioneering the then-unusual daily strip at the Los Angeles Examiner, and otherwise working as a journeyman cartoonist with a habit of focusing on characters that were “the other”—immigrants and the poor, especially.

Herriman debuted The Dingbat Family in 1910, a comic featuring a family that lives in a tenement beneath another family—never seen by them or the reader—whose noises and unexpected visitors become a point of obsession. Later named The Family Upstairs, the strip ran for six years. It was successful in its own right, but the real excitement comes from what happened in the “downstairs” of this strip.

William Randolph Hearst gave Herriman the greatest gift a comic artist can receive: space… With room to move, Krazy Kat became increasingly strange.

In a narrow panel at the bottom of the strip, Herriman drew a B-plot to the story, featuring small animals that comment ironically on the goings-on of the Dingbats while having their own simple adventures. This is where Krazy was born. Sweet but silly, the Kat was—of course—antagonized by a mouse, who in this case had a tendency to throw bricks. As Herriman once put it, Krazy Kat was created “to fill up the waste space.” And yet, he brought an innovative hand to the composition. In their first appearance, the Kat and mouse play marbles as the family quarrels; in the last panel, a marble falls through a hole beneath the bottom line of the strip.

This slapstick spent years “beneath” The Family Upstairs, but slowly the wordplay became cleverer and Krazy more philosophical. An unexpectedly literate strip-beneath-a-strip, Krazy Kat eventually broke free and became an independent strip in October 1913, running vertically down the newspaper page. A few years later, William Randolph Hearst gave Herriman the greatest gift a comic artist can receive: space. The publisher-turned-fan provided him with a full Sunday-page format for Krazy Kat, pointedly placed in the arts supplement of his newspaper rather than a kids’ section. In fact, Hearst designed the whole City Life section around the strip.

With room to move, Krazy Kat became increasingly strange. The pattern was patternless: Herriman’s pages might be crowded with text and startling shifts in landscape, or they might be airy, full of white space, a free of box panels. Herriman worked in broad pen strokes one week, and on a miniature scale the next. An “intermission” panel might appear in the center box of a 3-by-3-inch comic, or the page might be designed in circles or tilting vertical boxes. Occasionally, the characters broke the “fourth wall” to comment directly on Herriman’s drawing or to recognize themselves on the pages of a newspaper.

Herriman also used the gift of space—and, eventually, color—to richly mine the desert landscape of Coconino County, Arizona, home of the Grand Canyon. Mesas, cacti, adobe walls, and Joshua trees background the strip with an unearthly and absurd landscape. Their appearance inexplicably changes from panel to panel. Ignatz and Krazy might be talking as day and night change over indiscriminately; the skies might be marked in plaid, or stripes, or herringbone. A tiny bit of Navajo-painted pottery in one panel might soon become a tree. Unexplained shadows grow up behind the figures. Recognizable features of desert appear, like the “Mittens” of Monument Valley, but they are exaggerated, located where they shouldn’t be, and perhaps set alongside a scooped-out moon. Realism and surrealism coexist in Herriman’s world. In this comic strip, we are located in this world, and at the same time, not.

Krazy Kat is about obsession. The heart of Herriman’s humor is when obsession stretches into absurdity… But it is always shadowed by the futility of our personal crusades and the threat of it consuming us. We need too much.

The basic plot—the love triangle, the brick-throwing—created a familiar structure for readers that gave Herriman space to indulge the strangeness of the landscape, language, and characterization of Krazy Kat. He prevented the plot from becoming routine by playing with readers’ expectations of the formula—often the brick-throwing happens offstage, or is only set up, not executed, before the strip concludes. It is not a punch line, exactly. The reader is left to fill in the blank space.

In the end, Krazy Kat is about obsession. The heart of Herriman’s humor is when obsession stretches into absurdity or bumps up against the crusades of others. But it is always shadowed by the futility of our personal crusades and the threat of it consuming us. We need too much.

Unusually, Krazy Kat’s admirers included artists, writers, and art critics. Poet e.e. cummings wrote the introduction to the very first collection of Krazy Kat strips. Willem de Kooning was an avid fan, especially of the fanciful southwestern landscapes. So was Walt Disney. After Herriman’s death, Disney wrote to the artist’s daughter: “As one of the pioneers in the cartoon business, his contributions to it were so numerous that they may well never be estimated.”

H.L. Mencken loved Krazy Kat too, as did Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot. Jack Kerouac said the strip was a precursor to the Beat Generation, with common roots in “the glee of America, the honesty of America, its wild and self-believing individuality.” Even President Woodrow Wilson was a noted fan.

In what is almost certainly the first instance of an art critic taking comics seriously as art, Gilbert Seldes devoted a whole chapter to the strip in his 1924 book, The Seven Lively Arts. He wrote that the strip was “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.”

With such high-minded supporters, Krazy Kat got pushed into high culture. It was adapted as a Broadway musical in 1922. Herriman was inducted into Vanity Fair’s “Hall of Fame.” Hearst kept paying him well, and when Herriman tried to refuse a raise, Hearst overruled him. Though the artist was embarrassed by his income as a comic artist—750 dollars a week during the Depression—he was able to build a two-story, Spanish-style house above the Hollywood Bowl for his family. He had time to indulge other projects, like illustrating Don Marquis’s classic archy & mehitibel.

And yet, for all the high-minded acclaim, most readers didn’t like Krazy Kat. It had a tendency to bewilder the public. It never appeared in that many outlets, and reportedly remained in some of them only by Hearst’s direct order. By 1944, when the strip ended after Herriman’s death, it was appearing in only thirty-five newspapers.

It wasn’t that readers had any particular gripe with Krazy Kat, contends Richard Marschall in America’s Great Comic-Strip Artists. Its “popularity was limited not because readers were hostile—few readers understood Krazy Kat—but because most were too impatient to like it. In all of comic history, it was the strip that demanded the most attention—not necessarily sophistication, as is usually assumed—on the part of readers.”

After drawing about 3,000 Krazy Kat strips, Herriman died in Los Angeles at age sixty-three from “non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver.” Rather few people attended his funeral, though he was celebrated as a “saint” by those who did. As he wished, his ashes were scattered over the Monument Valley desert.

As for Krazy Kat, the era’s usual practice was to slot in another cartoonist to take over a syndicated strip and carry it forward. But here again Hearst made a choice that cut against his usual business habits: he promptly canceled the strip, rather than see it rendered in another hand.

But the questions that the artist refused to answer over the strip’s thirty-one-year run remain with us. Is Krazy Kat a parody of romance and conflict? A satiric commentary on authority and proscribed social roles? An allegory of reality and fantasy? Or is this over-thinking it—was it just a well-drawn comic strip about a cat and a mouse?

What is radical about Herriman’s work is that we can spend a century reading it and still know nothing for sure.

Anna Clark is a journalist living in Detroit. Her reporting, essays, and book reviews have appeared in The New Republic, Grantland, The American Prospect, Salon, The Christian Science Monitor, Next City, and many others. She is also a political media correspondent with the Columbia Journalism Review’s United States Project. A former Fulbright fellow in Kenya, Anna is a writer-in-residence in city high schools and the founder of Literary Detroit. She is at @annaleighclark.