Listen:

It starts as a fragment of sky

that detaches itself from the stratosphere,

something in my eye as I look up.

I call it the Land of the Dead,

its messenger gliding toward me,

star-ermine cape scalloped with black wings,

to land at the foot of the kapok tree

between buttresses

that remind me of the house we lived in once—

you said a gale had ripped off its roof.

Furniture inside for the afterlife—

and you laid out on the table,

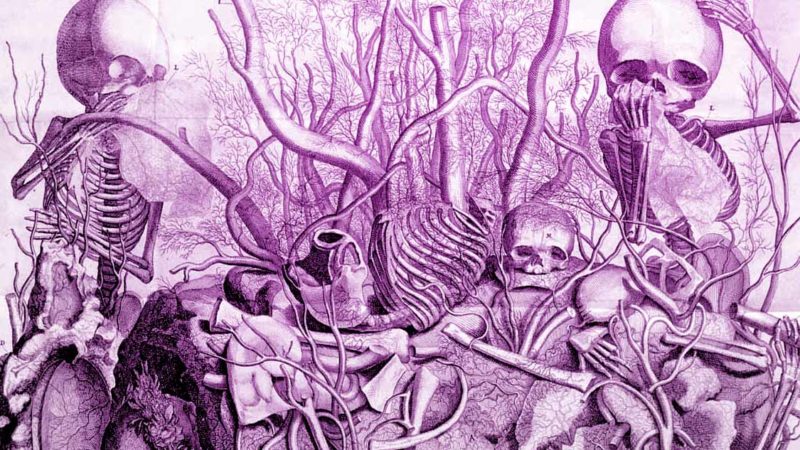

a skeleton curled like a foetus

that the king vultures pierce,

their beaks inside your bowel,

their heads painted with prisms,

their white eyes haloed with red.

Kings of light

who once wore the constellations as headdresses,

death eaters

now bringing up lumps of your flesh,

putrid at first, then sweet.

Maggots shrink back into eggs, flies buzz to their pupas.

If I sniff I can smell the stink that’s followed me ever since you died.

Who knows what the mind can do

but here your corpse

is becoming fragrant,

your face pointed east where the sun rises

as our family arrives,

their tears flowing up, back into their eyes,

their tissues folded into pockets.

They hug each other then carry you

into the hut, remove the herbs

packed in your heart, your intestines.

A brush paints backwards, removing the annatto dye

that’s protected me against your ghost,

dressing me in red jaguar clothes.

Now the surgeons arrive, scrub their hands, peel on stained

white gloves and green masks

and unpick the stitches across your abdomen,

a scalpel erases its cut,

iodine is wiped off your skin.

You wake as you are counting backwards. When you get to one,

the anaesthetist’s needle pops out of the cannula on your hand

and as the gurney is wheeled down corridors

the sedative wears off.

Now you’re back in the ward, anti-psychotics

sucked out of your blood into the saline drip.

Poisons rush up syringes; pills appear on your tongue

and fly back into nurses’ hands.

Your teeth plant themselves in your gums

and you menstruate.

Wrinkles smooth themselves out

as your hair grows auburn.

Here comes the hard part, the Land of the Dead

floating just above my head

because all along as you’ve been healing

I’ve been getting smaller until

I’m a newborn, resting against

the buttress of your thigh, a liana

linking me to you from my navel.

The kapok tree drops a shower of red blooms around me

as I cry out and take a sharp breath.

I’m lifted up, lowered into the ledge of your womb

where I settle in a foetal position facing east.

The king vultures have followed me in

and someone is zipping up my roof with a scalpel.

I squeeze my eyelids shut and my eyes sink into their sockets

then vanish.

My lips close and fuse.

My ears no longer hear your heart.

Silence.

I’ve gone back as far as I can. You must do the work now

my pregnant mother, you who once told me

what your psychiatrist said—that

you should never have had children.

You were crying at the time and I consoled you

in the hall of my bedsit, cradling the black phone.

The vultures stayed with me all my life. I wake some nights

and their starry heads are above me, as they were

when I lay inside you, my organs shining in the dark

like caskets of jewels to be plundered.