“How will I know if I’m getting better?” asks my teenage patient. I’m treating him for depression, and lately he’s been thinking about driving his car off the road. Tonight he drove to the emergency room instead. I don’t know what the “professional” response is to his question; medical school didn’t equip me with a stock response.

I glance at some notes I’ve scribbled on scrap paper. “Some people describe it as a lifting of a veil,” I try. “Others describe it as a weight off their chest. And some people just say that they feel like their old self again.” Yet my own recovery from depression has been more complicated: I’ve found that there is no return to a nondepressed self. There is only something new.

The depressed self, however, tends to reappear, and last year I noticed the familiar signs. In October, food tasted like dust. In November, my laugh felt different, less genuine. In December, I found I couldn’t tolerate the threat of a 4 p.m. sunset without a mouthful of whiskey.

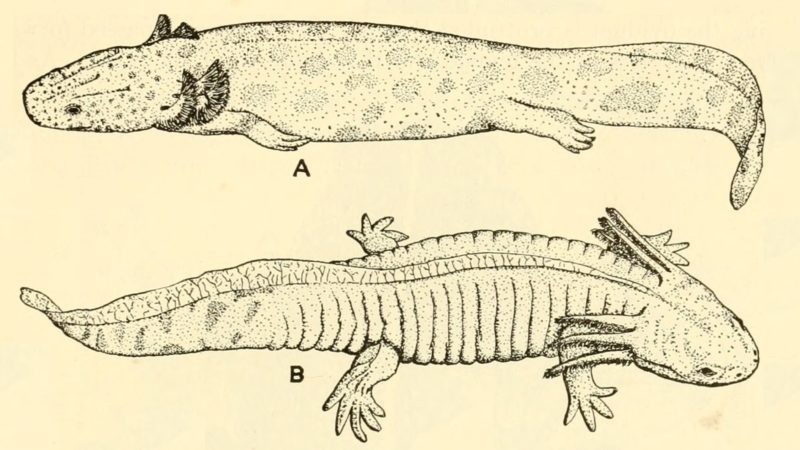

During those dark months, I read In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman. In one passage, Rahman describes the axolotl, an amphibian whose metamorphosis can be induced by an iodine injection. The axolotl grows up overnight, into an adult form that it never would have reached on its own. It becomes, irreversibly, a new creature, able to live on land for the first time.

In February, I scheduled an intake with an interventional psychiatrist to determine whether my depression was bad enough to warrant ketamine treatment. A part of me was prepared to hear that there was nothing wrong, no reason for treatment. But the psychiatrist prescribed the drug right away.

Unlike typical antidepressants, which increase the availability of serotonin in the brain, ketamine induces rapid synaptogenesis — it prompts the brain to create new connections. Increased serotonin may result in synaptogenesis and subsequent relief, but it takes weeks, if it works at all. On ketamine, the brain rapidly becomes limber, liberated. Imagine a cart on a weathered dirt path. Its wheels won’t readily deviate from the path’s well-worn impressions. But say one day it rains, smoothing the tracks. The cart can go any direction it wants. The brain is the cart. Ketamine is the rain.

At subanesthetic doses, ketamine produces a sense of detachment from one’s surroundings and self that can feel pleasant and dreamlike, particularly for a person in pain. But a bad trip on ketamine creates a nightmarish unreality in which one’s identity becomes remote and inaccessible, as if it has slipped in between dimensions.

The night before my first infusion, I was afraid. I was terrified of losing my self, despite the pain I was in. I was not prepared to leave the only reality I’d ever known.

When ketamine is squirted up your nose, the first sensation you notice is the bitter liquid dripping down the back of your throat, followed by a rapid decline in anxiety. You hadn’t realized that your muscles were tensed. You grasp for what you were thinking about earlier: Should your new bookshelf stand perpendicular to the bed or parallel? Maybe if you just decide now, you can stop worrying about it once and for all — parallel wall or perpendicular? Parallel or perpendicular parallel parawall Paragard pectoriloquy pectoral muscle — wait, what were you supposed to be thinking about? It was so important, and it had been bothering you all day. And then…the thought unspools.

And unfurls.

And you can see that your preoccupation was bullshit. Your mind wanders. It’s iterative. Creative. Expansive? There’s a movement, a warmth, a vibration humming in the back of your head.

When I tried ketamine, it worked, in the sense that for the first time I felt no pain. But the pain came later, when I grasped the truth: that I’d been depressed since I was a child, that those years were gone, that I could’ve felt better sooner if I’d admitted to myself how bad things were.

When I started this essay, I searched my journals, hoping I’d documented the threshold between depression and relief on my first day of treatment. But there’s no text in that night’s entry, just a hastily drawn sketch of the friendly axolotl, smiling at me, its mouth a tiny upside down ∆ — the mathematical symbol for change.