By Kenneth R. Rosen

The beating lasted thirty minutes. Then the dog was dead.

Alaska State Troopers found the dead puppy curled up by the kitchen sink, fresh contusions and lacerations across its head. Scattered around the floor nearby were shards of glass, all that remained of the kitchen oven window.

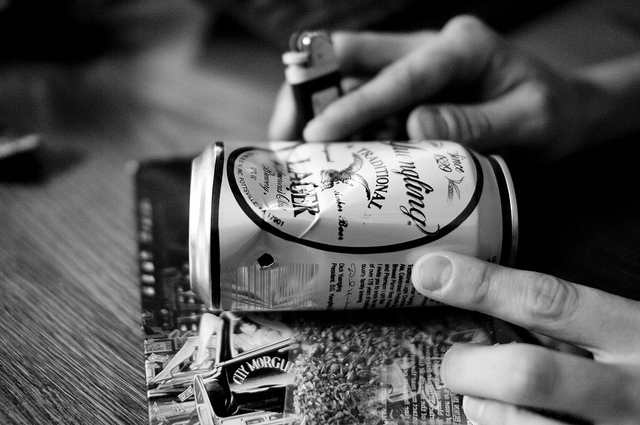

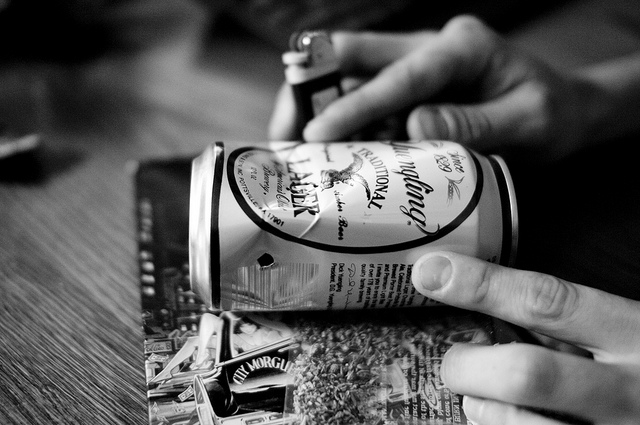

On the night before he killed his family’s two-month-old black Labrador, two years and four months after the State of Alaska outlawed chemicals used in synthetic cannabis, 22-year-old Kory Campbell stayed up smoking the drug known as Spice, or K2, at his home on Squire Drive in Houston, Alaska.

When he ran out of Spice, local media reported, he rampaged through the house.

The rural community of about 2,000 in the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, part of the Anchorage Metropolitan Statistical Area, is similar to other rural suburbs. Most roads lead to dense woodlands, connected by thin serpentine roads of dirt and gravel.

In Southcentral Alaska—between Anchorage to the south and Talkeetna to the north—the lone stretch of Highway 8 is a tarmac patrolled by State Troopers and the occasional ice-road trucker.

Farther west and to the north, on an island the size of a pin head no matter the map, is Diomede, population 70. The village outpost on the Arctic Ocean, near the edge of Siberia, saw its first Spice-related attack in the outset of 2011 when a 43-year-old man was arrested and charged with arson, having lost his mind and burned a neighbor’s house down.

The fifth largest controlled substance seized by Alaska State Police in 2014 was K2, at a street value of only a little more than $11,000 combined, yet arguably contributes to as many hospitalizations and emergency response statewide as cocaine, heroin and alcohol combined.

“Although complete studies have not been conducted,” the Alaska State Department concluded in its most recent annual drug report, “some of the side effects of synthetic cannabis consumption are heart palpitations, extreme agitation, vomiting, delusions, hallucinations, and panic attacks.”

Gone untreated, the drug, as any other, can lead to death.

A rough timeline of Spice-related incidents and their responses, nationwide and in Alaska, can confuse anyone—but they bear similarities.

Synthetics laced into inhalants or plants first made their way into the United States in December 2008, when a shipment was seized in Dayton, Ohio, according to the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Before 2010, synthetic cannabis remained elusive and unregulated by State or Federal agencies. By 2011, just before Gov. Parnell signed into law his state’s own bill to restrict the use, sale, and distribution of synthetic drugs, the DEA issued an emergency mandate to place eight types of synthetics under its control. All but three were later labeled as Schedule I substances.

House Bill 7 went into law on July 7, 2011, describing K2 and Spice as, “a combination of herbal and chemical compounds that commonly produce a reaction similar to the use of marijuana. The popularity is increasing, especially among youth, due to easy accessibility, low cost and the difficulty of detection on drug tests.”

While legislative frameworks were drawn up, regulating the sale of “incents” was aimed at alchemists who worked at home to produce their own mix of chemicals. These changes would reflect in the law, increasing the number of banned substances under Sec. 11.71.160. Schedule IIIA from 6 to 16 (sources show the increasing complexity posed to regulators in specialized fields not their own) overnight.

Yet the substances, lawmakers and law enforcement authorities believe, come from Asia where the chemical makeup continues changing as statutes lag several years behind, tied up in legislative knotting.

As more product reached Alaska, shipped often through the United States Postal Service (perhaps the practice of package screenings adopted by the UPS and FedEx could stymie drug trafficking before it begins), Mr. Campbell and Diomede were experiencing some of the state’s first encounters with the drug before its recent outbreak.

In the spring of 2013, some twenty-three stores in Anchorage were found selling the drug. In January 2014, the city assembly made law a ban on packaging and a list of labeling criteria for Spice and similar products that influenced a later statewide ban.

What we can learn from Alaska’s battle against synthetics is something of a national model (if not a could-be testing ground) that is slow to take hold elsewhere.

Shortly after that, Spice and K2 were no longer seen anywhere.

Ever since then, the State of Alaska’s ongoing battle has all but slowed. While I lived there, reporting on education and the city and borough for the Juneau Empire, I saw its lingering effects. It’d been a few years since I first tried Spice, long before it reached the mainstream of the continental United States, when it was still just something brought home by friends who served in conflicts overseas. And while cities like Portland, Oregon, Bangor, Maine and New York today fight to combat a slow incursion of similar drugs, the ongoing battle on the Last Frontier is one that deserves commendation if not recognition.

Findings of several studies and reports, both from federal and state agencies and the Alaska State Department of Corrections released over the last half decade, suggest that statewide and nationally there is a need more than ever for treatment over incarceration. Recidivism and drug-related fatalities are products of neglect. They amount to costly oversights caused in part by failing state and federal funding that equal a balance often paid in carnage and in death.

Even in New York City, five psychiatric care patients were hospitalized this year after smoking Spice. One man leaped into the Hudson River, and over the course of one week 160 people were hospitalized, with some 1,900 emergency visits in April and June alone, prompting Governor Andrew Cuomo to call for stricter legislation to ban new substances.

What we can learn from Alaska’s battle against synthetics, the spread of the industry from the Southeast region to the Arctic Circle in the Far North region of the state, from the juveniles selling and smoking Spice to the elderly and homeless who quickly die from its effects, is something of a national model (if not a could-be testing ground) that is slow to take hold elsewhere. It is also exemplary in its efforts, something perhaps impelled by current drug laws and enforcement practices, to lower youth and adult recidivism while bolstering addiction treatment in a place that is often relegated to neglect.

But that has served this state well—Alaskans learn to combat afflictions with a signature grit not seen anywhere else—as it serves to represent a microcosm of the inefficiencies and difficulties faced with drug-related violence and incarceration around the country.

When the Alaska Department of Corrections released its 2015 Recidivism Reduction Plan in February, the findings were met with little ado—states like Connecticut, Maryland, Washington and Florida have all in the last half-decade released similar, hopeful reports on their intentions to lower incarceration rates and, perhaps more ambitious of them, recidivism rates among youth and adult offenders.

Alaskans learn to combat afflictions with a signature grit not seen anywhere else—as it serves to represent a microcosm of the inefficiencies and difficulties faced with drug-related violence and incarceration around the country.

What is striking is the lack of resources at hand: the state of Alaska is operating at 101 percent capacity, even after the completion of the Goose Creek Correctional Center, a 1,536-bed medium-security prison for men in Wasilla, outside of Anchorage.

“If unabated, Alaska’s annual 3 percent prison population growth will soon result in the need to construct a new expensive prison,” the report found.

Prison growth in Alaska far surpasses the state’s population growth even with crime reduction seen statewide. Some 255,310 people in the state were convicted since 1980 of at least one misdemeanor or felony offence, nearly half the population of Alaska or, perhaps more shocking, about the same as the city of Buffalo, New York.

Further, the report concluded that, “the vast majority of these citizens are subject to one or more collateral consequences as a result of conviction.”

But of course, recidivism, with some states following up after only six months then never again, others counting adjudications and not corrections placement, is not an exact science. Reporting can never be certain. Focusing on drug rehabilitation to curb the initial processing of juveniles, and the recidivism for adults, however, is more plausible and feasible.

Substance use impacts the ADOC population at a rate of 15 percent higher than all United States inmates combined. A report released in 2010 by The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University concluded that 65 percent of all U.S. inmates met the Diagnostic Statistics Manual criteria for substance abuse addiction. But only 11 percent received attention that supports recovery.

The study also found, perhaps most obvious but never overstated, that in 2006 alone, drugs or alcohol contributed nationwide to 78 percent of violent crimes, 83 percent of property crimes like breaking and interning and theft, and 77 percent of probation violations such as public disorder.

To understand the problems faced by Anchorage, the state’s largest metropolitan area, we could look toward Fairbanks—about the size of the state capital of Juneau, both with populations of about 32,000—and see a nuanced version of the widening cracks in successful youth rehabilitation and recidivism.

When a federal sting of three smoke shops in Fairbanks in 2013 netted some $750,000 of Spice, the substances failed to violate federal law, and no one was charged with possession of the drugs. But in 2014, the owners of The Scentz, Mr. Rock & Roll, and The Smoke Shop, all in Fairbanks, were charged with “delivery of misbranded drugs received in interstate commerce, a misdemeanor,” according to reports at the time.

Fairbanks, Alaska’s largest city in the interior is home of the Fairbanks Native Association and an indicator of faults in the state’s treatment of drug offenders throughout the state. Perry R. Ahsogeak Director, FNA Behavioral Health, oversees 50 beds at four treatment facilities around the city. Expanded efforts between the state Department of Corrections and residential treatment centers offer adults, more so than juveniles, an effective means for reintegration and treatment once they are released, a practice that, the state says, has proven effective in Juneau.

“Adults [have] higher success rate but that’s really due to the services that are provided,” Mr. Ahsogeak told me. “Adults have access to 45‐day as well as two, four to six months programs. Youth have one four to six month program. With this in mind, bed availability is limited.”

Space is often limited because funding is skimp and hard to acquire, and staff turnover presents another challenge.

“I have 120 plus positions within the Behavioral Health Division,” he said. “With the number of employees needed as well as the need for credential employees there [are] always vacancies and the challenge of finding qualified compassionate people.”

Summertime Uptick

In June, the Center for Disease Control learned of an uptick in calls to U.S. poison centers that catered to users suffering from the adverse effects of Spice use. The National Poison Data System noted that calls increased 330 percent between January and April. This was a 229 percent increase in calls during the same period the year before.

Though it is still one of the top ten states for youth recidivism, and though youthful males and minorities occupy the highest rate of recidivism, the state managed to lower drug offense among juveniles by 19.1 percent

The CDC noted that increasing and varying cannabinoid synthetics with higher toxicities, and an increase in call volume to poison centers “might suggest that synthetic cannabinoids pose an emerging public health threat.”

No kidding.

While Alaska continues to snub its battle with drug addiction and the emerging persistence of Spice, a control board is moving forward to seek out legislation to direct the regulation, distribution and consumption of marijuana, the sale of which was legalized in February. Though perhaps more regulations on use are less needed than oversight on treatment. If one is meant to prevent the other, which should take precedence when the alternative is failing?

Since this summer, a spike in use, arrests and hospitalizations have centered around Anchorage. On Aug. 10, the Anchorage Police Department announced it had responded to 88 Spice-related emergencies since the beginning of the month. Three days later, that number rose to 110.

Bean’s Café, a homeless shelter and cafeteria on East Third Avenue in Downtown Anchorage, has for the past two years seen the deaths of many customers.

A steady flow of ambulance and emergency service personnel continue to respond to the location as patrons are found staggering, then later unresponsive, heads slumped forward, under a sky that each summer never seems to darken.

Though it is still one of the top ten states for youth recidivism, and though youthful males and minorities occupy the highest rate of recidivism, the state managed to lower drug offense among juveniles by 19.1 percent, a change so great that the findings of the study urged the state’s adult criminal justice system to issue mandates similar to those found effective for juveniles: evidence-based practices, implementation of risk assessment tools, matching clients with services to benefit their needs. In other words, rehabilitative services work.

This is all to the state’s credit and detriment. While there is much good (state funding that does support rehabilitation, alternatives to youth incarceration, active awareness programs), there is much that needs fixing—more attention and directed efforts at preventing rather than saving. For America, it’s a place to begin looking for answers in dealing with the crippled criminal justice system, drug offences, and somewhere that practices can become effective sooner than elsewhere.

However, despite successful efforts toward restricting the procurement and sale of illegal substances much like the synthetics known as Spice, state monies, much like the rest of the nation, are being used for reactionary measures rather than preventative means.

While Alaska nears something of a prescriptive solution to plights elsewhere, a fixable corollary of a larger issue nationwide, it’s too expensive for juveniles or the elderly and displaced to leave Alaska, no matter the age, even if they sought help on their own in another state.

In spite of this, perhaps because of it, the steady flow of magenta lights and sirens are never ending.

Lisa Sauder, the owner of Bean’s, knows the flashing lights well. Ms. Sauder has seem more than 22 of her clients die this year, nearing the 31 she lost to spice the year before.

“It’s like a war zone,” she told the Anchorage Dispatch News. “This is just out of control.”

Kenneth R. Rosen works and writes for The New York Times.