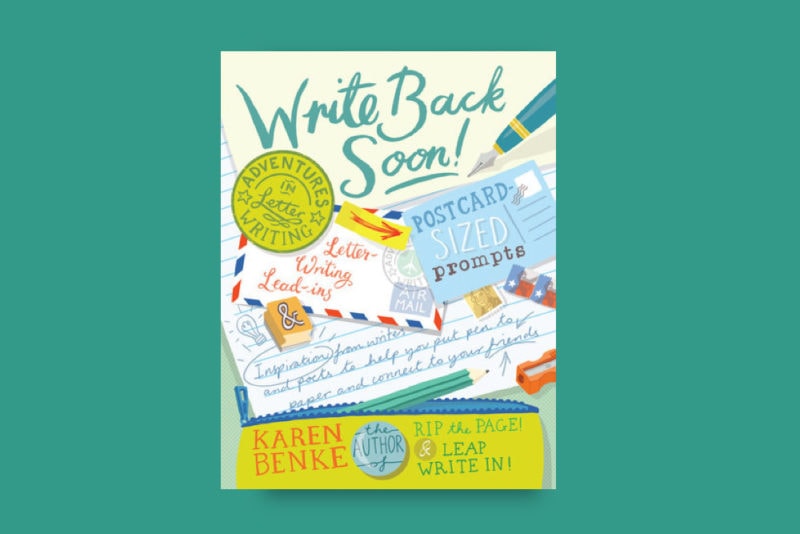

In Karen Benke’s latest book, Write Back Soon! Adventures In Letter Writing (September 2015), more than a dozen writers including Neil Gaiman, Natalie Goldberg, Jane Hirshfield, Wendy Mass, Gary Snyder, Ruth Ozeki, and others, offer their insights on the lost art of letter writing. Each writer has something different to offer about the power of the pen, the possibility of connection, and the silly but weighty relevance of a messy process. The fun prompts and wide-ranging essays cover a lot of ground and reminds us that the best kind of writing not only connects us with others but also to ourselves.

In Write Back Soon, Wendy Mass confronts screen culture head on: An email from my grandmother would look just like an email from anyone else. The typed words temporarily filling my screen would be whisked away in a few seconds as I opened the next email in my inbox. Since it’s incredibly rare to actually print out an email, I will almost certainly never lay eyes on it again. But a handwritten letter from my grandmother, written on thin, lilac-scented paper in her delicate script becomes a sacred object.

Alison Luterman takes the confessional route: A Confession: I like my own handwriting. It isn’t beautiful, or orderly. The j’s and g’s and y’s are hard to tell apart, t’s go uncrossed and i’s undotted, and the whole thing slants alarmingly across the white page like a drunken polar bear’s tracks across the tundra. But that’s what I like about it, its imperfections, even its illegibility. It’s mine.

The ever-fantastical Neil Gaiman lets us in on part of the details of his quirky writing process: Working in fountain pen is good because it slows me down just enough to keep my handwriting legible. Often I use two pens with different ink, so I can tell visually how much I did each day.

Beyond the reflective benefits, writing letters by hand has other psychological perks. According to memory medic Dr. William R. Klemm, “Research highlights the hand’s unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas. Virginia Berninger, a professor at the University of Washington, reported her study of children in grades two, four and six that revealed they wrote more words, faster, and expressed more ideas when writing essays by hand versus with a keyboard.” Turns out letter writing is not only good for our friendships, it’s good for our brains too. But unlike playing a musical instrument, which requires financial upkeep, letter writing is in fact an equal opportunity exercise.

Benke isn’t alone in her endeavors to revive the lost art. Writers, artists, design professionals, and educators are coming together across the country to run groups like Handwritten that partner with organizations like LetterFarms, CursiveLogic, TypeLetters, The 1,000 Journals Project, and The Sketchbook Project. All of these groups reinforce an appreciation for handmade work, kinesthetic processes, and interactive exchanges through writing and art.

I had a chance to speak with Benke about why writing letters still matters, and why she thinks teaching children is a radical act of creativity.

–Raluca Albu for Guernica

Guernica: Letter writing has been described as a lost art. Recently, there was an exhibit at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art showcasing the handwritten letters of famous historical figures (Twain, Jefferson, Hemingway). They included love letters, thank you notes, hand printed news records, creative and elaborate penned info-graphics. There’s a whole science evolving around the preservation of these things, the interpretative possibility these documents hold as clues to our past. But I find it funny, maybe even sad, that letter writing is now getting exiled to archival museum halls. Does this art form need need reviving?

Benke: I think letter writing is a lost art to some of us who find it easy (too easy) to fire off text messages and who rely solely on email for correspondence. For those in my mother and grandmother’s generations, letter writing–thankfully–still feels intact and like a living, breathing thing.

For younger folks, letter writing hasn’t even been “born” and definitely requires more attention. I have 8, 9, 10, 11-year-olds in my creative writing workshops who don’t know their own addresses, or what a return address is and where to place a zip code. “Zip code? What’s that?!”

We need to revive letter writing. We need to do it to slow us down, and return us to the present moment, where many of us are spending less and less time. Writing by hand helps us to slow down, organize our thoughts, make contact with the details of our lives and ask questions of those we care most about.

My work is political in that I believe the way we feel about ourselves is the most important feeling we’ll ever have and taking time to connect to someone else creates a feedback loop of sorts — this has to have a positive effect in the world.

Guernica: That reminds me of a quote by Francine Prose where she likens handwriting to historical excavation, “Like seeing a photograph of yourself as a child, encountering handwriting that you know was once yours but that now seems only dimly familiar can inspire a confrontation with the mystery of time.” What are some contemporary, and maybe less obvious, epistolary favorites that might reveal some of the lifeblood that still exists in letter writing?

Benke: Ava Dellaira wrote the beautiful and perfect book Love Letters to the Dead. She tipped me off to The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky who she used to work for. The film version of Perks is one of my all time favorites for it’s accuracy of what it feels like to be in high school and to know you’re left of center from the herd and then to find a group of other artistic souls who you can share your vision of the world. There’s also the book Letters From a Nut by Ted L. Nancy has an introduction from Jerry Seinfeld, and is a great example of how fun it is to write in a personae.

31 Letters and 13 Dreams has resided on my bookshelf since I was an undergraduate and my first poetry instructor Gary Thompson (a student of Dick Hugo) played “mailman” during poetry workshop. We wrote letters in class to fellow students, telling them what we liked about their poems, and Gary delivered them. Gary often read from 31 Letters and 13 Dreams to inspire us to dive deeper into our creative lives.

My son, Collin, and I have read and re-read Dear George Clooney, Please Marry My Mother many times, out loud to each other and to ourselves. We re-read certain passages and still laugh after multiple readings. Wip-smart dialog. A third grade teacher at Tam Valley Elementary School named Karen O’Toole is a big supporter of creative writing every day for her third graders. She recommended The Day the Crayons Quit. A book anyone any age will enjoy and relate to.

Guernica: I noticed that you’re interested in the deeper adult motivations for letter writing and its psychological implications, but you have some lighter, more playful parts to your message too. Many of the writers you worked with on this book are young adult novelists or children’s book writers. Why did you make this choice?

Benke: I learn best and feel most calm, thereby retaining what I’ve learned, when something is explained to me slowly and clearly, and a bit playfully. Kids help inspire me to strive toward this ‘method’ of teaching both myself and others. I read something recently that Elizabeth Gilbert shared about how her husband—whose first language is not English—often will say, “If you explain it to me slowly, I’ll understand quickly.” I love this. Writing for a younger audience slows me down and this is a practice I’m continually learning from: slowing it all way down.

I can tend toward wanting to get a lot done in a short amount of time. Not that doing things fast is bad, it’s just that sometimes it revs me up so that I miss out on the small details of life. Setting an even pace while living a writing life is crucial, I find. When I’m slowing it down—my life, my thoughts, my to-do lists, that’s when I get to notice the extraordinary in the ordinary.

I like and want to actively cherish moments. And then write about them. Kids live in the present and are great teachers for me for this. RIP THE PAGE! is for elementary aged children and LEAP WRITE IN! is for teens and young adults. Ultimately these books are versatile and writing teachers can use them for all ages. The joys of writing for children—especially when putting RIP THE PAGE! together let me see and re-inhabit the world through their eyes and ears and behold the magic and excitement of why writing can feel at once challenging and exhilarating. I write creative writing adventure books to help kids feel inspired to reach for a pen. One of my students said it best: “When I write a poem, it un-builds the walls.”

My approach is to share something that I’m authentically passionate about in the moment and then to hold space and get out of the way, so that those I’m writing with can have their experience of playing with similes or metaphors or writing in a different personae, or finishing a fragment or free associating. Also they can experiment with writing within a formal structure of an American haiku, haibun, or pantoum, three of my current favorites.

What I’ve learned from the response of kids (teachers and parents) is that they do best when I’m operating in the moment and responding as authentically as I can. When I look, see, tell the truth—in whatever form the truth is arriving—is of paramount importance. It’s what we’re all hungering for anyway, real connection. This lesson has been taught from my best teachers, the kids, who by their authenticity and presence have helped make my writing more honest, more playful. I’ve learned to be a better—deeper—listener from my students too. I think we’re all teachers and students at the same time, all the time, dancing this dance back and forth. I like to spend time with kids because I sometimes take a too serious approach to life, slip into seeing a situation as dire, especially if I read the morning news before I write. Kids loosen me up and remind me to connect, to burn away the ego, find the line of the poem or story that brings the most joy.

Reviving letter writing? For younger folks, letter writing hasn’t even been ‘born.’

Guernica: Do you consider your work to be political in any way?

Benke: My Poets in the Schools colleagues from California (where I worked for 20+ years while writing my books) like to say that we are instigators when we enter a classroom. So in that way, I guess I do consider my work to be political. I encourage students I work with to disagree with me and push back, to trust themselves first. Unconsciously every time I step into a classroom or space where I’m looked at as “the expert” in some way, I’m unconsciously, in a myriad of small ways, telling those listening to me to write like me. When I share this with students, I follow up by insisting that I don’t really want them to write like me, I want them to write like them. I don’t want them to follow the rules if following the rules means they aren’t going to get knee deep in their own truth.

Sometimes we write lying down, sitting in the hall, barricaded under a desk or outside under a tree. We actively aim to change our way of looking so we can see fresh again. No easy task. With letter and note writing, I’m encouraging the screens to be moved aside. I assure students who have a particular affinity for their screens that they can come back later. I assure them I’m not anti-screen, since I text and email with the best of them. But there’s this hunger for connection (I know I feel it) and when we stop to write by hand, to reach into ourselves and connect with someone on the page with a pen, it has a calming effect. Our essence through handwritten words, through taking our time to craft a little note or letter or poem that we send through the mail, causes a little positive ripple in the world. Maybe we then venture out and write a letter of support or protest or stand up for someone who can’t write.

Penning a note or letter helps us tap into our humanity and creativity that tapping buttons on a screen just doesn’t. We get to reflect about our lives in relation to another life, return to an earlier time or tell about the ordinary of our day. This reaching out to another and then our anticipation of this offering being met and received, opened, and read, is a gift to both the recipient and us.

My work is political in that I believe the way we feel about ourselves is the most important feeling we’ll ever have and taking time to connect to someone else in a thoughtful, playful, spontaneous way, to remind someone they matter to us via this simple act of time spent, creates a feedback loop of sorts, of kindness, compassion, gratitude in both parties. This has to have a positive effect in the world.

I learn best and feel most calm, thereby retaining what I’ve learned, when something is explained to me slowly and clearly, and a bit playfully.

Guernica: Write Back Soon started out as a kid’s project, even though it’s broadened out to adult interests as well.

Benke: I was going through a divorce, moving from a beloved home where I’d raised my son, written three books, and led writing workshops for over 15 years. It wasn’t the best time to be in the public eye of promoting a new book and teaching, and I wasn’t yet ready to start book four either. I wasn’t sleeping much and, well, I had no idea what I wanted to write about next. As you might imagine, it was an in-between-sort-of-time where much was in flux. But since I love (and need) to always have a writing project in the wings and have always been a big fan of snail mail to calm, center, and connect with those I love, I decided to start writing letters with a different kind of focus.

One of my students from years back was featured in a story that ran in the local paper about how she started a hand-written story called Wild Tales that she sent out for adults and children. Something sparked inside of me and I’ve learned to pay attention to those sparks. Maybe I could write a Museletter of sorts and send it out to children.

Sylvia—that third grader I had in my Poets in the Schools workshop long ago—was inspiring me to tap into my own brand of magic via hand-written letters. I put a little write up about The Museletter out to my list—I send out an electronic version of the Museletter once a season—to inspire the inner poet (maker) in all of us. Then I waited.

The response was immediate and favourable. I picked up my pen and started to surprise myself and hoped that the kids I sent the Museletter to would like getting an envelope with their name handwritten in different colors each month, with a special surprise, of course, tucked inside. Each Museletter contained a wacky writing prompt from one of my books, an example poem or story excerpt from a student writer, a book recommendation, a quote from my literary assistant Cat Clive, and some sort of simple tactile gift that might inspire a poem, story, smile—magic word tickets, a small clay fish, a feather, a skipping stone, piece of eucalyptus bark to use as a bookmark, stick of gum piece of peppermint candy. The Museletter travelled to seven states and three countries and was a lot of fun to create.

Guernica: That sounds fun, like you went from one hopeful project to another. Do you think the future of communication in general is doomed or are you optimistic?

Benke: Oh, I’m definitely optimistic. Whenever someone asks what my newest creative writing book is about and I say “Writing by hand and sending notes and letters,” the responses I get are nostalgic and heart-felt. People light up and want to share their stories of letter writing, of how much it means to them. Letter writing bridges the loneliness created by screens.