In April 2012, Guggenheim Foundation Director Richard Armstrong announced the launch of a new initiative designed to “challenge [the Guggenheim’s] Western-centric view of art history”: the UBS MAP Global Art Initiative. This initiative, sponsored by Swiss banking giant UBS, brings contemporary “non-Western” art from South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and North Africa into the traditionally Western bastion of the Guggenheim.

It is both surprising and revealing that undertaking such a task is still necessary in 2013, but in New York, the history of exhibits featuring contemporary Asian art is short. In a discussion held last September by New York’s Asia Society, President Emerita Vishakha Desai reflected on the reluctance of the Western art world to recognize the legitimacy of contemporary Asian art until as recently as the 1990s.

“If you did Asian art history, you would not do anything beyond the 19th century,” said Desai of her own experience studying art history in Michigan, having come from a family of art collectors in India. “It was accepted wisdom that everything beyond that was impure, copying the West, it was not authentic, and therefore you didn’t study it.” Contemporary works from the region, particularly because they are seen to use so-called “Western” forms, have been perceived as derivative because of their deviation from the traditional forms associated with pre-19th century art from Asian countries. One of Desai’s early fights to gain recognition for contemporary Asian art revolved around how artistic influence itself was being defined.

Viewing the non-Western world as an unchanging repository of “tradition” and the West as the rightful home of modernity lead to the neglect of contemporary Asian artists whose works aimed to meaningfully engage with the modern Asian experience.

“Just because I wear Western clothes, it doesn’t make me the same as somebody else who is Euro-American. And I refuse to be defined only by what I wear, which is in a way what happens to artists…If you define artists only by how they paint, you’re not looking at the context…When Impressionists are looking at African art or Japanese prints—[like] Van Gogh—we call them ‘original’…When an Asian artist looks at Western art and uses a Picasso-like motif, we say ‘derivative’.” According to Desai, such thinking not only took away the creative agency of contemporary Asian artists, but also ignored the specific experiences and perspectives expressed by their works.

The pervasive view of the non-Western world as an unchanging repository of “tradition” and the West as the rightful home of modernity lead to the neglect of contemporary Asian artists whose works aimed to meaningfully engage with the modern Asian experience. But due to the efforts of curators like Apinan Poshyananda and Desai, as well as New York Times critic Holland Cotter, contemporary Asian art began to receive more attention in New York in the 1990s. Early exhibits like Traditions/Tensions: Contemporary Art in Asia (1996) and Inside Out: New Chinese Art (1998-1999) began to change how Asian art was perceived and valued in the West. Traditions/Tensions was hailed as the first and largest showing of contemporary Asian art, and of art made by living Asian artists. Both exhibits dealt explicitly with the tensions between tradition and modernity resulting from rapid economic, political and social changes taking place in the region during the ’90s, as well as the impact of these changes on identity and nationhood.

The subsequent rise and growing commercial success of contemporary Asian artworks both within their home countries as well as abroad is a story still unfolding. Knight Frank’s World Wealth Report 2013 not only confirmed the rapid growth in investments in fine art, but also that China is now the world’s largest market for art. The report also notes that the world’s top-selling artists at auction in 2011 were Chinese modernists. This suggests a gradual relocation in both the production and consumption of art to Asia, and major players have clearly taken notice. While no definitive figures are publicly available, the New York Times surmised that UBS has pumped in upwards of $40 million into the MAP Initiative. This is all to say that the newfound (and close) attention being paid to contemporary Asian art doesn’t stem solely from ideological altruism; serious financial returns are anticipated.

38-year-old Singaporean June Yap is the first of three regional curators who will complete a two-year residency at the Guggenheim. She has spent the last year travelling around South and South East Asia in pursuit of what the museum has described as “the most compelling and innovative voices in South and Southeast Asia today” for the MAP Initiative’s first exhibit, No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia.

Financial motivations aside, the Global MAP Initiative’s regional exhibits can of course raise the profiles of local artists and by doing so, simultaneously diversify the canons of Western art. More importantly, however, by bringing in experts like Yap, the initiative provides a significant institutional platform for curators to use their intimate understanding of regional culture and politics to frame artistic developments for international audiences.

“Curating is not a neutral exercise… Curating is my interpretation of what is going on,” Yap says of her work. No Country is a collection of contemporary painting, sculpture, photography, video and installation by twenty artists (several of international renown) and collectives from Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. What emerges is the sense of a complex and polymorphous region.

The work suggests that knowledge is partial and contingent; the transient experience of an encounter should, if anything, prompt an examination of one’s own beliefs.

When Yap was first chosen by the Guggenheim to curate an exhibit focusing on South and Southeast Asia, she already knew that she wanted to approach art from the region in a way that resisted the simple formula of artworks as direct representations of the region. Most of all, Yap wanted to put together an exhibit that would “challenge romanticized perceptions of the region.” She had already curated exhibitions of Asian art for Western audiences before. In 2009, she worked on Paradise is Elsewhere at the Ifa Gallery in Berlin, a show that examined ideas of paradise from the perspective of artists from the Asia-Pacific.

“When I started producing exhibitions for institutions that were not from my own country, I had to take on a different position. I had to try and see what the region, these artists and these works looked like through someone else’s eyes,” muses Yap. So for the Berlin exhibit, Yap intentionally picked pieces that she hoped would seem ordinary—that is, not “exotic”—to her viewers. “It is not to deny that people see the region as exotic,” explains Yap. “But how do you engage with that? I think you [her audience at the Ifa Gallery] are quite exotic as well. Now, let’s have that conversation…” This impulse to return the gaze runs equally strongly through No Country.

The current exhibit’s title is itself illustrative of the unruly, mongrel path of cultural influence that the exhibit seeks to embody. The phrase “no country” is taken from the first lines of Irish poet W. B. Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium.” Yeats aimed to evoke the pains of aging and the individual’s creative quest through a journey to the heart of the Byzantine empire. His words also inspired American writer Cormac McCarthy to explore similar themes in a very different context—drug trafficking along the US-Mexico border—in his 2005 novel, No Country for Old Men. For Yap, the reasoning behind the show’s title is self-evident; it is about the moment of migration, and the physical and metaphysical significance of crossing boundaries.

“No Country is about borderlessness,” says Yap. She is interested in exploring the permeability of national borders, and by extension, the performative nature of national and cultural identity. While Yap acknowledges that “there are real borders with real guns”, it is the historical and imagined transgression of borders that animates No Country.

Several of the pieces in this exhibit tangibly capture the fractures in the modern Asian nation-state. Enemy’s Enemy: Monument to a Monument by Tuan Andrew Nguyen is an American baseball bat into which is carved the figure of a monk who immolated himself in protest against the Diêm regime in Vietnam in 1963. White Stupa Doesn’t Need Gold, a piece depicting an unembellished Buddhist pagoda by Burmese artist Aung Myint, is a critique of “favoring appearance over substance,” a clear reference to how political repression has functioned in her own country.

Other pieces play with these ideas without offering definitive answers. One of the most compelling pieces on view is Counter Acts, by Filipino artist Poklong Anading. This black-and-white lightbox shows a group of people holding up circular mirrors to cover their faces, which in turn reflect the bright sunlight in which they’ve been photographed. The first from a larger series called Anonymity, this piece is strategically placed at the start of the exhibit because it embodies a particular approach Yap encourages visitors to take, both to the region and to the exhibit. Because the subjects are holding up mirrors, neither viewer nor subject can see the other. Instead of the sunlight ‘illuminating’ (literally and metaphorically) the encounter, it obscures it. Pieces like Anading’s suggest that knowledge is partial and contingent, and the transient experience of an encounter should, if anything, prompt an examination of one’s own beliefs.

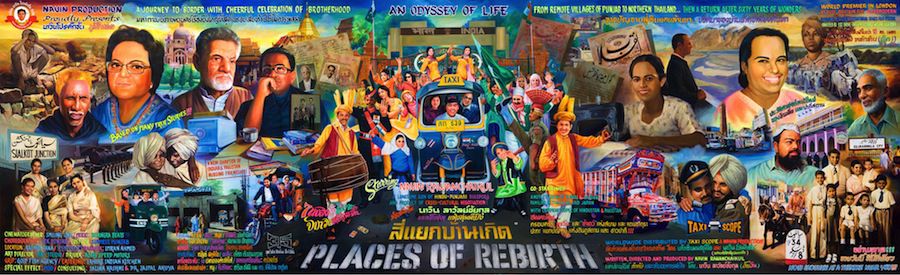

Places of Rebirth by Thai artist Navin Rawanchaikul, is a large Bollywood-style poster, tracing the passage of the artist and his Japanese family through the Indo-Pakistan border on a tuk-tuk, ostensibly a continuation of the idea that countries in the region have traded both people and cultural influence across borders. To anyone from the region, the colors, images and idiom of Rawanchaikul’s piece may appear banal, even a brash capitalization on the appeal of a different kind of exotica—Asian popular culture—with its prosaic mockery of Indo-Pak brotherhood and kaleidoscopic portrayal of the Taj Mahal, dancing women, smiling brown children and men in colorful outfits beating drums. Even taking into account Rawanchaikul’s signature playfulness, one could question the extent to which such works subvert stereotypical images of the region and refocus the gaze of the so-called ‘Western’ viewer. But to Yap, highlighting attempts within the region to depict one another is valuable for its own sake. Rawanchaikul’s piece can be seen as disrupting the Orientalist impulse on a different register: by showing how difference is perceived even among Asian countries.

Identity is ultimately the wreckage that emerges from the battering of history’s cultural storms.

Keeping Up with the Abdullahs 1 and 2, for example, by Malaysian photographer Vincent Leong, show how Indian, Chinese and Islamic influence and ethnicity are inextricably interwoven into the fabric of Malaysia’s history and people. In keeping with the central theme of No Country, that nations and cultures are not discrete, watertight entities, such pieces also depict how identity is ultimately the wreckage that emerges from the battering of history’s cultural storms.

One of the fundamental and perhaps intentional paradoxes of No Country is that it is using a national metaphor to make a point about how the region as a whole is perceived—how can one’s understanding of the fluidity of national boundaries inform how we think about regional divisions and, by extension, a perception of the region as homogeneously “Asian?”

The exhibit, while a celebration of the vision and labor of promising new artists from the region, is also meant to spark an interest in contemporary Asian art that outlasts its run. A long-term impact on the Guggenheim is expected: the museum’s permanent collection, which previously contained few works from South and Southeast Asia, will be augmented by pieces from the current exhibit.

No Country is scheduled to tour the Asia Society in Hong Kong this October and is expected to travel on to a venue in Singapore at a later date. Given the centrality of looking in the exhibit, one wonders about how regional audiences will react. Yap says that the same exhibit that she hoped would complicate perceptions of Asia and Asian art in New York, will in South and Southeast Asia attempt to spark a completely different conversation: “When it goes back to Asia, we’re going to be talking about the politics…the things that we presumably share, and the things that keep us apart.”

Yap shares Pakistani art historian Iftikhar Dadi’s sense of the importance of the curator as an agent for change, particularly within the region. “I think intelligent curatorial practice can contribute to how we imagine cultures, how we interact with various cultures,” says Yap. “But at the same time…its efficacy is disputable, right? It’s not like you look at an artwork and your life changes…Change takes time. Curating can precipitate change. Maybe the change will take fifty years. Is it still considered change, if it happens at such a gradual pace? Does it still count?”

But, as the history of contemporary Asian art in the West already attests, it does count; every exhibit paves the way for the next.