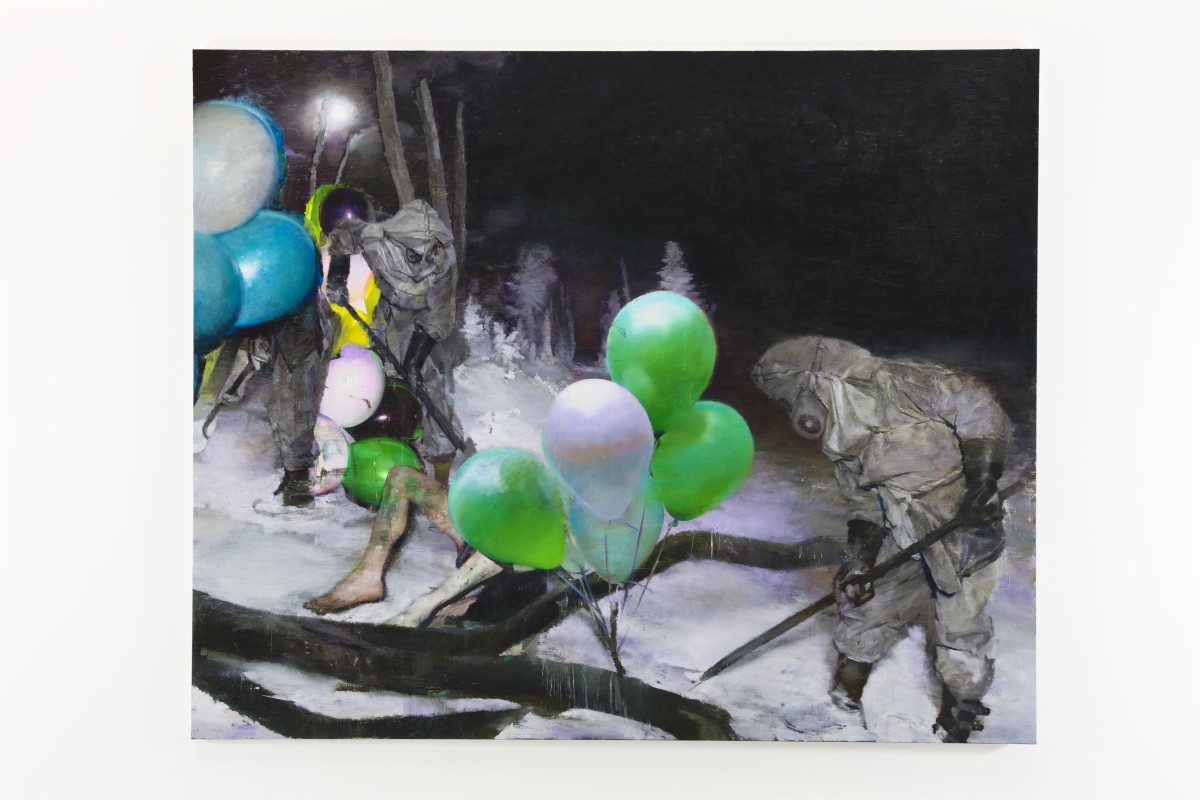

Justin Mortimer likes when people look at his paintings and get the sense that they’ve missed something that’s just happened. The London-based artist works from collaged photographs he’s found on the Internet or in second-hand books, and paints them in new contexts on large canvases. The bodies are often contorted—children with limbs bent by genetic anomaly, soldiers doing calisthenics, porn actors mid-performance—and the action of the final composition is ambiguous, implied, or partially hidden. In a recent series, bunches of balloons dominated the foreground of battlefields and operating rooms, and parts of prone bodies (possibly corpses) jutted out from behind them. For Mortimer, the balloons are intended to be both sardonically festive—one curator-critic has called them a nod to the post-recession hangover of the 1990s “Party decade”—and also a more heavily anxiety-laden image, meant to evoke pustules and whatever else might spontaneously burst forth from our skin.

Two paintings that tread similar ground—“Tract” and “Hex”—are hanging now in Haunch of Venison’s Chelsea gallery as part of a group exhibit called “How to Tell the Future from the Past.” The show’s artists are an international crowd and their works are formally and topically diverse—an unsettling, fetus-like mass with hair and fins hanging from the ceiling; a sprawling, tiled sculpture recalling the blind-men-and-the-elephant parable; a three-panel video playing the same train-ride shots of Central Asia simultaneously backward, forward, and stalled. The linking topic, according to the gallery, is humanity’s “endless return to a base nature,” a theme that resonates with much of Mortimer’s work in his depiction of the violence, both implied and overt, of modern institutions.

“Tract” is an expansive nighttime scene with a shadowy forest background that sets a tone similar to certain stock-footage from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. Its centerpiece is a pair of bodies: a naked toddler standing behind a man, bent at the waist, whose face and action is obscured, in part by hanging laundry; it might be a de-contextualized bathroom scene of a child watching her father shave, except we can see both of their shadows on the trees, placing them unmistakably in the forest and implying something stranger and perhaps more foreboding. “Hex” is a much-smaller headshot of a veteran following reconstructive surgery. In the back of the gallery, Mortimer and I discussed these paintings, the sinister nature of medical machinery, and the anger that drives his work.

“How to Tell the Future from the Past” runs from January 17 to March 2.

—Reed Cooley for Guernica

Guernica: Does the historical context of the photographs you use as source material influence the themes of the final painting?

Justin Mortimer: I suppose it does because I know where the images came from. Maybe it’s an undisclosed vein that’s still there in my mind. For example, in the past I’ve painted quite explicit genocide pictures, but I’ve taken them out of context and put them into another space. But they remain genocidal paintings.

Guernica: I was interested to read that one of your sources for collage photographs is pornography. Your paintings are full of naked bodies, but they aren’t often explicitly sexual.

When people are involved in sex acts there’s a twist or a tipping, a bit like a rococo sculpture of the Virgin.

Justin Mortimer: Yeah, the final images aren’t sexual. I did a series of works for my L.A. show where I was using vintage gay porn. I used this 1980s/1990s German skin mag. This was quite bog-standard, bad photography. You get the flash around a thigh or the flash lighting just delineates the form. The image becomes very exposed, very vivisected. This cruel exposure of the body was very attractive for me conceptually, but also important was the way the body becomes cropped, so you just see parts. There’s something interesting about the fact that people are coming, but it might look like they’re being executed or tortured. You don’t see photographs of people in those positions normally. When people are involved in sex acts there’s a twist or a tipping, a bit like a rococo sculpture of the Virgin. It’s that point where the body is between falling and stasis: the physical imbalance is attractive; there’s an unfulfilled energy to it.

Guernica: If nudity isn’t sexual in your images, does it have another meaning?

Justin Mortimer: Yea, I think it’s vulnerability. I was using a lot of naturism photography a few years ago. Naturism is a sort of utopian idea. It was present in 1930s Germany and 1950s America. For me there was this sort of lovely freedom to it, but it also reminds me of photographs of people being stripped before they’re executed. I wanted to suggest that in the paintings: people being dragged out of their homes, humiliated, stripped, shot. We’ve all seen the photographs of 1940s Europe with the pits.

Guernica: Scenes of war and scenes of Western medicine seem to predominate in your work. Is there a connection between these realms?

Frankly, I’m not a clever enough artist to be explicit; I think it would be quite banal. I think the imaginative possibilities are much stronger.

Justin Mortimer: These are two subjects I’m very interested in. I think I’ve just allowed my unconscious to put them together and explore, and it’s ended up with this third subject that I wasn’t expecting. Medical machinery has always been fascinating for me, since I was a young boy. I was in the hospital myself a lot as a child; I used to wear a caliper, I was x-rayed all the time, and I saw lots of sick children. I have memories of being in medical machinery; it’s very frightening to a young kid: they move around and make strange noises; doctors manipulate you. I suppose as an adult [that’s translated to] thinking about exploitation and vulnerability. And then I’m from a military family—my father was a helicopter pilot in the Navy when I was a child—so I was surrounded by military hardware. I suppose both things just got embedded in my mind.

Guernica: So there’s a personal origin for each.

Justin Mortimer: Yes, and my dad went off to sea throughout my childhood. There was always a sense of ‘would he come home’—that childhood fear. Fear became a subject—a personal fear and also a fear I have for mankind; it’s become a subject by accident.

Guernica: Your paintings often feature bodies that could be construed as victims, but there never seems to be a visible villain. Why is that?

Justin Mortimer: I like my work to be quite non-explicit. In some ways I want to show the deed, but I don’t want to show the deed. So, is what’s happening in the piece the result of an action that I’m painting? Is it an action that’s about to happen? I’d also like to set up the idea that the viewer could be the protagonist in the drama. So, are you, the viewer, actually the person who’s controlling what’s happening in the picture-space? In “Tract,” there’s a shadow at the bottom of the painting, which could almost be cast by the head of the viewer. I like the idea that you are possibly viewing what’s happening, but you can’t really see it. I like to make you think you’ve got to go around objects to try to imagine what’s happening behind them. Frankly, I’m not a clever enough artist to be explicit; I think it would be quite banal. I think the imaginative possibilities are much stronger.

Guernica: Do the bodies in “Tract” come from separate photographs?

I’m very aware that I’m making a career of selling Fabergé eggs to people. I’m in the sort of classic liberal trap; I’m an essentially left wing person, making very bourgeois objects.

Justin Mortimer: Yes, the child is from a medical textbook. She’s got a slight curvature of the spine or something. I was photographed like that as a boy, because my tibia is bent and weird, quite anomalously, and no one knows why. I remember being taken to a hospital studio and photographed for medical books and that feeling of being stared at. I think that brings back the question of why I was interested in these guys in the funny 1980s German porn: They’re being stared at and they’ve been manipulated and choreographed—probably because they were skint, they were poor, picked up in a club. The man in “Tract” is just an Internet photograph of Americana—probably a 1950s photo of a young G.I. recruit.

Guernica: Do you find the gritty theme of this exhibit at all at odds with its setting in Chelsea—this safe, extremely upscale neighborhood?

Justin Mortimer: We’re in ground zero of the international art world, aren’t we? Everything we’re looking at here is a luxury good for the super rich. I know in America you donate things to museums and there’s that sort of patronage. But let’s face it: This work goes to people who live in very swanky places that .001 percent of the population—not the American population, but the world population—could afford. So I’m very aware that I’m making a career of selling Fabergé eggs to people. I’m in the sort of classic liberal trap; I’m an essentially left wing person, making very bourgeois objects. But I do want my paintings to engage on a very human level. It has by default become this luxury object, but what makes me want to make art in my studio in a dingy part of East London is that story I want to tell about our fears, our anxieties, how afraid we all are, how we’re all going to die. Are we going to go mad? Am I going to lose my job? Is my body going to fail? Will my loved ones not be around for me? There’s sort of an existential anger—not to sound pretentious—but there is an anger I have in me that drives my work.

Reed Cooley is an Editorial Assistant at Guernica Daily.