By Juan Villoro

Translated from the Spanish by Francisco Cantú

A few days ago I saw a poster depicting a spectrum of violence ordered from 0 to 30. With careful attention, crimes of various types were ranked according to their severity. The most egregious categories are Rape (28), Mutilation (29), and Murder (30). Launched in 2011, the Violence-Meter is part of an initiative promoted by Mexico’s Secretariat of Public Education, Mexico City’s National Polytechnic Institute, and the National Women’s Institute. In a country where every morning brings a new tally of dead bodies and where the femicides of Ciudad Júarez have yet to be solved, it is essential to remain aware of distinct levels of aggression and their cumulative impact. The Violence-Meter is a necessary tool for measuring our reality.

Nevertheless, I am struck by the first category: Hurtful jokes (0). Do verbal insults carry no consequences? Do they really represent a zero degree of aggression? The subsequent values are: Blackmail (1), and Lying/Deception (2). Obviously, they are subjective notions. A lie can be less offensive than a taunt. But it seems strange that no quantifiable damage is attributed to the hurtful joke, a variation of the insult where irony serves an ambiguous purpose (to disguise an emphasized subtext). “It was just a joke, suck it up!” the aggressor says. The Violence-Meter suggests that to cause pain under the guise of a joke somehow nullifies its impact, equivalent to zero. We take for granted that this is how we must live.

In our billfolds we carry a pantheon of murdered heroes, victorious generals, persecuted dignitaries.

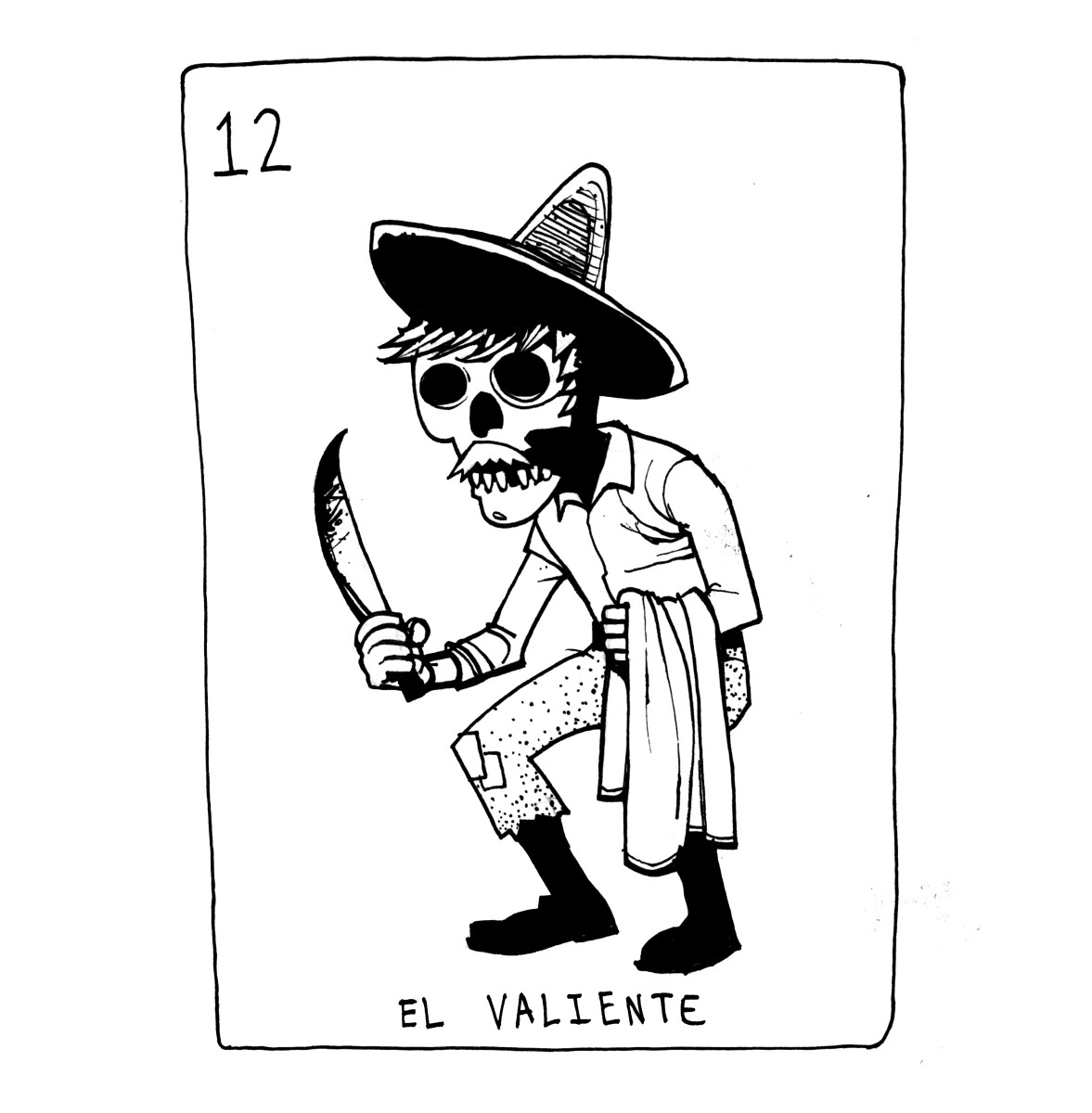

It is compelling to consider the many symbols of violence our country regards as natural. In Mexico’s iconic card game Lotería, “The Brave Man” (El Valiente) is depicted holding a knife stained with blood. In traditional gameplay, the introduction of the card is announced by the dealer (el cantor) with the following riddle: “Why do you run, coward, carrying such a fine knife?” Since Lotería’s arrival in Mexico during the second half of the 18th century, courage has been represented at public festivals by a sociopath armed with a dagger.

And what about Mexico’s national anthem? One afternoon in 1853, Guadalupe González del Pino locked away her fiancé, poet Francisco González Bocanegra, so that he might pen verses suitable for entry in a national competition. Over the course of four hours the prisoner imagined demolishing the door with artillery fire. The result was the bombastic inanity that to this day represents Mexico in international arenas. Fortunately, almost no one understands what we say. We announce ourselves “at the cry of war” and, if habit and memory allow us to arrive at verse six, we propose: “May your countryside be irrigated with blood / May their feet trod upon blood.” Several years ago, the philosopher Antonio Alatorre, author of The 1001 Years of the Spanish Language, suggested that our anthem should have lyrics more in line with Mexico’s contemporary ideals. The civic poetry of Ramón López Velarde or José Emilio Pacheco represents us much better than an invitation to leave blood-soaked footprints everywhere we go. That today’s anthem resulted from an initiative by Mexico’s long-ruling military dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna should be enough reason to replace it with another.

And what about Mexico’s coat of arms? The image of the eagle and snake, central to the legendary founding of Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City), is too powerful to be dismissed outright, but it could accommodate a change of design. Our coat of arms is the only one that depicts an act of of predation. If the flag of South Korea represents the complementary energy of opposites by depicting the emblem of yin and yang, our flag stands for the annihilation of one opposite by the other. Article 2 of Mexico’s Law on the National Coat of Arms, Flag, and Anthem underscores the warlike condition of the emblem: “The National Coat of Arms consists of a Mexican eagle…with wings…spread in the act of combat…its left talon perched atop a flowering prickly pear cactus growing on a rock emerging from a lake, its right grasping a curved serpent, its beak open to devour it.” What does this say of our national identity? These few sentences would surely register on the Violence-Meter.

The banknotes of our national currency also promote disorder. In our billfolds we carry a pantheon of murdered heroes, victorious generals, persecuted dignitaries. The only figure that never participated in combat is the 17th century poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. In Japan, today’s banknotes commemorate scientific and cultural accomplishments. The protagonists are the bacteriologist Hideo Noguchi, the writer Ichiyo Higuchi, and the philosopher Yukichi Fukuzawa, who compiled the first Japanese-English dictionary and founded the University of Keio.

Thoughtlessly, unconsciously, we damage words.

Tradition is not closed territory—on the contrary, its validity is subject to the necessities of the present. To redefine ourselves in accordance with contemporary values is a worthwhile endeavor.

The work begins with language. In colloquial Mexican speech, “execute” is used as a synonym for murder, as if death were a form of legal redress. Thoughtlessly, unconsciously, we damage words. When journalists say that someone was “lifted” (levantado) instead of kidnapped, or they refer to a body hanging from a bridge “like a piñata,” they transform outrage into something habitual, inscribed in custom. Horror must not be normalized.

On the Violence-Meter, no offense should be tolerated as a zero. The fight against violence passes through every corner of our shared society.

Originally published as “Violentómetro” in Reforma, 30 December 2011

© Juan Villoro, Agencia Reforma