In June, I visited Josh Kline’s solo exhibition, Project for a New American Century, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. I found, to my surprise, my own name on one of the wall labels. I worked as a production and editing assistant on one of his video projects in early 2015. Kline was making art and I, though certainly interested in his art, was making money. I couldn’t have imagined that my name would end up alongside his work. Who among us knows the names of the workshop assistants who made dogs out of stainless-steel balloons? Like most of the art world, I accepted my role as invisible labor within a larger hierarchy.

Acknowledging the people behind his art is only one aspect of how Kline investigates the contemporary art world and, by extension, the role of labor in our world at large. The often paradoxical layers of meaning in Josh’s work make it difficult to define and fascinating to talk about. He brings blue-collar workers into gallery spaces that traditionally exclude them. He experiments with new technologies while remaining skeptical and critical of their promise. He embraces dark, dystopian visions while believing in the power of rational optimism and utopian imagination.

Project for a New American Century displays videos, sculptural works, and multimedia installations from the past decade of Kline’s career. Many of these works incorporate twenty-first-century technologies, such as 3D printing and image manipulation, to explore changes in labor and capital in the U.S. and beyond. I spoke to Kline about how he envisions humanity in these inhuman contexts and what sort of future these inquiries lead him to imagine.

— Mengyin Lin for Guernica

Guernica: Can we start by talking a bit about the title of the show? The word “project” has become synonymous with “work,” which your art explores. How do you intend this title to be read as the opening sentence of your show?

Josh Kline: “Project for the New American Century” was the name of one of the main neoconservative think tanks in the ‘90s. Many of the architects of the Iraq War came out of there. I made the title a little less definitive and took it as my own. I liked the irony of it: the neoconservative agenda is a failed project, and in a way its failures have paved the way for the potential end of a US-led global order. But this is all still TBD. At the beginning of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, it also seemed like maybe the US was on the brink of collapse, and then it became the most powerful country on earth. The twentieth century has been characterized as the “American Century” because of the outsized global military, political, and cultural reach of the US during that time.

The show considers a second American century and what that would look like. What kind of future is the US building? For better or for worse, we’re still living in the world that the US built, in the American empire. The US still has the largest military on earth. The dollar is still the global currency. People still wear blue jeans all over the world. The United States seems to be conjuring up a century of climate disasters and artificial intelligence (AI) catastrophes. Fake news, alternative facts, and emergent authoritarianism are all over the world because, in some ways, of technologies that come from the US. My work is about the twenty-first century, but it’s hard to talk about our time without dealing with the USA.

Guernica: While your work employs technologies such as 3D printing and deepfakes, it is also skeptical of them, especially as they relate to the future of humanity. Can you elaborate on this complicated nature of your work?

Kline: Formally, I see everything as potential material, of course with moral and ethical limits. I am more interested in sampling than in appropriation. Appropriation is basically like, there is this thing in the world and you take it completely out of context and then point at it, whereas sampling is about creating language out of references — a language that moves in nonlinear ways and that has nonlinear relationships, including referring back to and commenting on its sources.

I often work with the technologies I’m interested in unpacking. Their use is a way to bring reality into the gallery. It’s similar to working with ready-mades, but in a much more complicated and complex way. Using these technologies allows me to understand how they work, to understand where they’re going and what their inherent possibilities are, and also what their flaws and dangers might be. For instance, working with 3D-printing has helped me understand what additive manufacturing could mean when it someday becomes widespread.

Guernica: For your work Unemployment, you interviewed unemployed workers about their relationship to labor and compensation. You also used 3D scanning to create 3D-printed portraits of their bodies, paying them to pose for the scans. What purpose did this additional step of 3D scanning technology serve?

Kline: Making work with 3D scanning has been a way to understand the ramifications of digitization, of our personal information and histories, but also of our biometric information. I started to understand that all the information that’s being digitized about people — whether it’s through biometric acquisition of personal information, or the skimming and vacuuming up of information as they shop online, or when their medical records are sent to the health insurance company they work with, etc. — is a way of cloning those people, of harvesting identities. All the information that’s leaking out of you all day long is forming these images of you: information-based clones that can answer questions about you without your consent.

Guernica: And do you feel that art has a way to engage critically with these technologies that is different from the way that corporations use them?

Kline: I do. I haven’t seen any corporations using these technologies to critique anything. That’s what art can do. Art is a reflection of the society in which it’s made.

3D scanning serves as a metaphor in my work. Because of the way it captures the whole body, I think it’s also a clearer and more meaningful way to represent these kinds of processes than a two-dimensional photograph would be. It’s a closer representation of the real world, which isn’t flat. Thinking about how AI and other forms of automation are digitizing and replicating human skills and then displacing people from their jobs — using these technologies doesn’t just represent this process in the gallery. The technologies bring it inside and confront the viewer with it.

Guernica: While technology plays a big role in your work, I find that humanity is always at the center of it all. In both Blue Collars and Unemployment, you displayed 3D-printed portraits of real people in a way that alienates their humanity — severed limbs in a shopping cart, a human body in a tied-up recycling bag on the floor. At the same time, you engage closely with your models, asking them questions and listening to their stories. What is your approach to toggling between humanness and the way in which labor or work strips us of it?

Kline: I am fundamentally a humanist. When I make these works, it’s not about representing how I view people. It’s about how I see people being treated under capitalism and in our society. The portraits of people in the recycling bags — those works are a way of illustrating how people become a waste product in our economic system. It comes back to this phrase from economics, “human capital.”

What does it mean for people to be treated as capital instead of human beings? It means that they can be used up and then discarded. One of those people I scanned was a secretary at a church, and she didn’t know how to use social media. So she was fired and replaced with someone who could post on Facebook about church events. Another person was a lawyer, an in-house counsel at a company for more than two decades. When she was fired, she had nowhere to go and burned through her savings without having found a new job. What does that make her? If you wait tables at Applebee’s or deliver packages for FedEx, you take on an identity when you wear those uniforms. People treat you like a product instead of a person. I wanted to find a way of portraying this reality viscerally that would stick with the viewer.

Guernica: It’s quite confrontational.

Kline: It needs to be. I think we see a lot of images of suffering, of people being exploited on the news, and we don’t retain any of it. Those images have lost their ability to affect us, whereas three-dimensional sculptures, I think, still have it. You go into a gallery and there’s this reaction you have, which might no longer be possible with most images because we see so many of them.

But at the same time, I want to preserve the stories of those workers. In the video interviews the workers appear intact as people and speak in their own words about their own lives.

Guernica: How does your artwork and the technologies it employs mediate between those stories and the audience in a gallery?

Kline: I think a lot about the audience and how to open up the work without dumbing it down. Someone who doesn’t have an education in art history should be able to get most of the meaning. My audience shouldn’t need a press release to understand what they’re looking at, especially if it’s in their own country.

Guernica: I appreciate that openness about your work, because sometimes I feel that certain contemporary art becomes gatekeeping — almost like the artwork intentionally obfuscates the viewer. And I imagine, and maybe this is my wild speculation, that some artists take pride in people not understanding their work.

Kline: Yeah, they revel in it. There’s a lot of exclusion, especially class-based exclusion, in the art world. And a lot of this is being perpetrated by people who claim to be Marxists, which is always hilarious. There is one very well-regarded white male artist I know who wrote a whole book about denying the audience. It’s a kind of nihilism, but it’s also white privilege. Like, if you’re denying people entry into your work in this way, keeping out everyone but a very small cadre of elite white intellectuals and rich art collectors, how is this any different from all the other white supremacy and white privilege in our society?

Guernica: At the root, it’s the same logic.

Kline: Yeah, it’s entirely the same.

Guernica: Do you show your work to people you worked with? Your subjects, so to speak?

Kline: I do. My studio manager and I went through all the records and contact information of people I’ve worked with, and I invited everyone to come to the Whitney for one of the openings. One of the FedEx delivery workers came to the opening with his daughter. He doesn’t work at FedEx anymore and has moved on to a better job. His daughter is in high school studying art. He had seen images of the work, but had never seen the sculpture or his interview in person before. Aleyda, the housekeeper in a downtown hotel who also appears in the show, came to see the work when I first made it. She brought her sister and her son. I interviewed her after that and asked her what she thought. When I was making the work, I told her what I was going to do, asking if she was comfortable with it, so she knew what she was going to see. When she came to the gallery, she and her sister were taking selfies with the sculptures. And she was like, “This is me. This is my life.” She understood very well what the work was about and what it meant. This conversation is in the video, too.

Guernica: In a way, the people in your work might not be considered by museums and galleries as a “museum general audience.”

Kline: Maybe this is the fault of artists. If art spoke more to working people or to people without an arts education, maybe they would go to see more art. Maybe there would be a larger audience for art if it was about things that were relevant to somebody who has to work in our society. If the work about Marxism actually dealt with working people, maybe they would come to museums.

Guernica: Over the years, your work has investigated a spectrum of labor and work — blue-collar workers in Blue Collars, middle-class workers in Unemployment, creative workers in Creative Labor. How did you become so interested in labor as a subject?

Kline: The earliest body of work shown at the Whitney is my work about creative labor from the early 2010s, about the people I saw around me. As I started showing in larger institutions and also showing outside of the US, I started to question why I was so focused on making work about such a small group of very privileged people in New York, about the creative class. I thought about this a lot when Amazon Prime was blowing up around 2014, as I watched all these FedEx workers delivering Amazon packages. I started to speculate about why there were so few images of contemporary working people in contemporary art. There’s a long history of representing labor in art. How can you really think about precarity in the twenty-first century without dealing with these people, these jobs?

Around the same time, I started thinking about the global north’s middle classes, who seemed destined to experience the same kind of dislocations due to automation that blue-collar workers had been experiencing. What we know as “the middle class” is an artifact of industrial civilization; an AI-driven, automated civilization is something else. It’s not the same thing at all. Then the question is, what comes on the other side of AI? Corporations want to save money by using AI to do everything, but what do we want? What do human beings want?

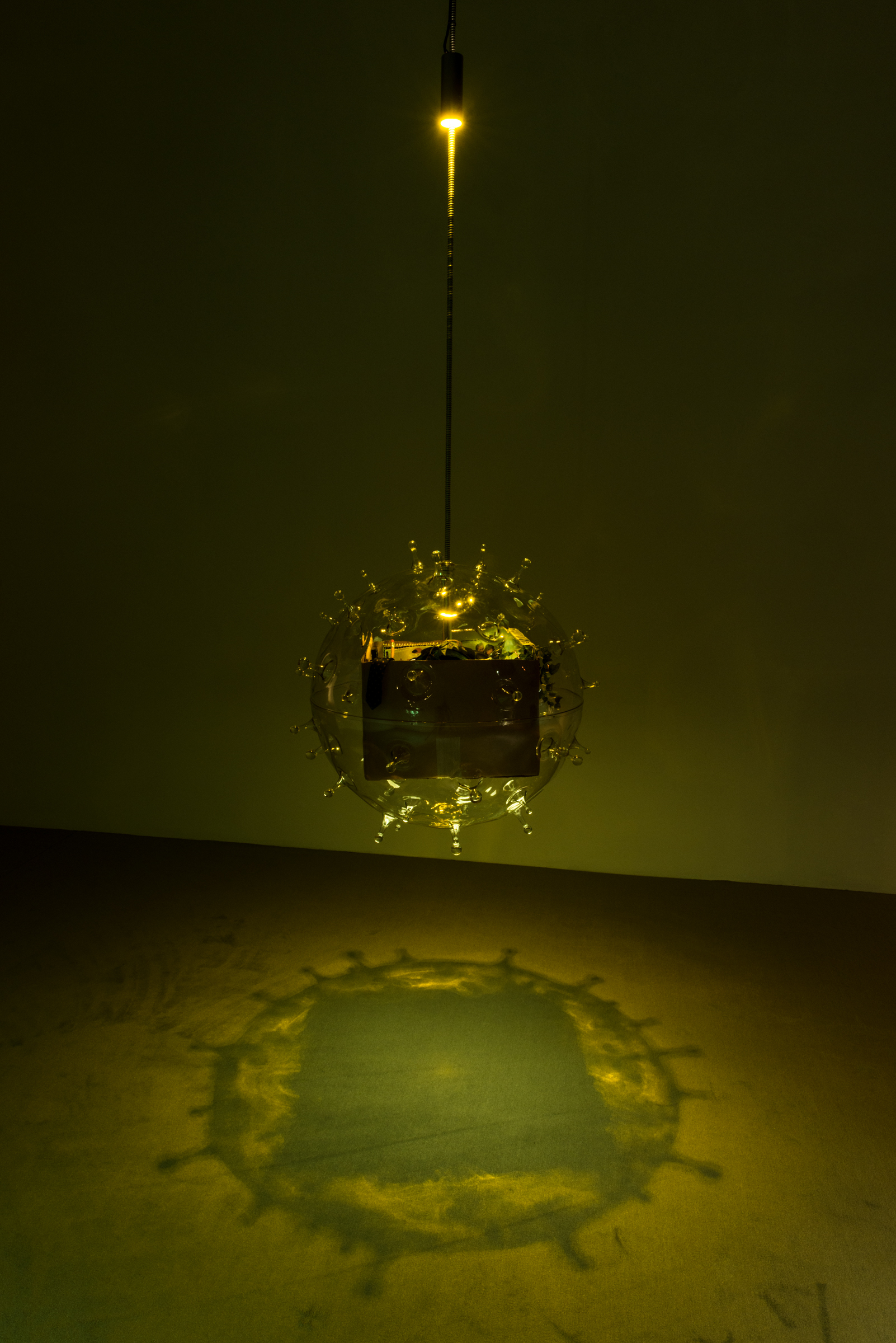

Guernica: You explore that human desire, the contemporary human experience, with both real and fictional human beings. For example, in the Contagious Employment sculptures, the characters are fictional.

Kline: I had this image in my mind of unemployment as a disease, and of these viruses hanging in space. I think I already knew that there would be file boxes. However it happened, once it ended up being file boxes of personal possessions, I had to figure out what those possessions were, who were these fictional people.

Guernica: Do you think technology alters our relationship to both fiction and reality?

Kline: Absolutely. A lot of my work deals with how technology is making it difficult to discern what’s real. Even before the Republican Party popularized the terms “fake news” and “alternative facts,” I was making work, especially in video, about a world where reality is manipulated through disinformation. Disinformation has been with us for a long time. The proto-deepfake videos that I made with face replacement software are all about the creative rewriting of history. Americans are a deeply irrational and ahistorical people. Sometimes you need to meet your audience where they live.

Guernica: Though much of your work can be described as dystopian, your experiments with utopian visions are quite powerful. How do you see utopian art? Is it doomed to be corny or misinterpreted as satire, or can it guide us to imagine a better (for a lack of better word) future?

Kline: The three-channel film, Another America is Possible, is an attempt at depicting a radical utopia. It presents an image of a wholesome and joyous future. The main channel, presented as a large projection, shows diverse people having a summer cookout on the lawn. Then on the other two channels, which appear as smaller projections in the installation, those same smiling people are burying and burning Confederate flags.

The final parts of this big cycle of installations that I’m working on will be utopian. But whether people will recognize it as utopian, I don’t know. Creating utopian art is really hard. A lot of people go into art exhibitions assuming that everything is going to be either ironic or critical. If you have something that’s neither ironic nor critical, but has a specific political position, and it’s presenting an image of the future that is sincere, there are people who refuse to believe that sincerity. For me, the three-channel film is entirely sincere. That’s the future that I want to live in. Whether I’ve succeeded at convincing other people that it would be a beautiful future, I don’t know.

Universal Early Retirement is a fictional commercial. I had already interviewed the people who appear in the Unemployment Bodies sculptures — those people in the bags. I interviewed them about universal basic income. I asked them what they thought about it. They all hated it. But when I rephrased it as, “What would you do if you won the lottery and all your needs were met?” None of them said, “Oh, I would just stay home and watch TV.” They all had goals. “I would volunteer in my community.” “I would go back to school.” “I would take care of my elderly parents, my children.” “I would spend more time with my loved ones.” “I would become an artist.” “I would work in the garden.” “I would do all this stuff that I can’t afford to do but that I actually dream about doing.” And then that became the script for the commercial. It was about selling universal basic income through these things that people actually want to do with their lives. So coming out of those two rooms of Unemployment at the Whitney where you face total dystopia, these commercials are an alternative. What if we took care of people instead?

Guernica: In a way, commercials are inherently utopian.

Kline: Yeah, they’re about desire.

Guernica: Dystopia and utopia are opposite to each other, at least on the surface, and you’ve found your way into both.

Kline: Real societies are always somewhere in between. And utopias can often become dystopias. When we worked together on Crying Games in 2015, I would talk about the US as a kind of soft dystopia — and the wider world beyond it as also a soft dystopia. Meaning that for a lot of people, life goes on in a kind of middle-class normality, but nearby there is horror. When you’re eating your avocado toast at a restaurant in New York, you’re not having a dystopian moment, personally. But the person who’s delivering the avocados for Fresh Direct, maybe they’re living in a dystopia, you know what I mean? And we all move in and out of it. In 2020, though, we were all living in dystopia. It became a hard dystopia . . .

Guernica: But at the same time, for some people, staying at home had utopian aspects.

Kline: That is where I was going with this. It was a truly dystopian moment in history with millions of people dying everywhere, people losing their jobs. But at the same time, there were so many moments in the summer of 2020 that were astonishing in New York. If you were middle class, you probably didn’t have to work. You were just hanging out in parks or marching in the streets. You had all this leisure time. You were wearing a mask and probably afraid of breathing the air, but you also had all this time restored in your life. But for the “essential workers” it was truly brutal. It’s a mixed condition. In my short film Adaptation, yes, New York is flooded. Yes, it’s dystopian. But as long as there are humans to live it, life goes on.