Few writers are able to bring together the global intricacies and upheaval of the Thatcherite era as well as Jonathan Weisman does in his new novel, No. 4 Imperial Lane (released by Twelve Books, August 4, 2015). The novel alternates between the settings of Brighton, England, in the 1980s, a time Jason Croley has referred to as the “decade of convulsion,” and colonial Angola in the 1970s, where the war for independence thunders through the private walls of a family drama. Weisman does all this with expert ease, humor, and psychological insight.

Though the novel is a coming-of-age story, it’s also a lighthearted exploration of how geopolitical forces shape a family history. It fully succeeds at being immersive and engaging as the story swings from scenes in embassy backrooms to pot-filled dormitories, recountings of lost loves, and flashbacks to front-line colonial battlefields. There is no way to get bored reading this book, and even when you finally do find a moment to set it aside, you might just go down a Wikipedia rabbit hole researching things you wish you knew a whole lot more about.

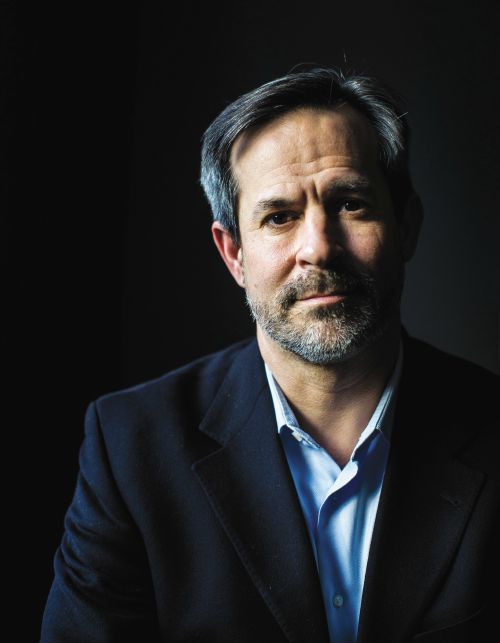

Weisman, an economic policy reporter for the New York Times, is one of those rare writers who can produce precise and exigent reportage but also imaginative, exciting fiction. For this interview, I spoke to him about writing across genres, how his life experiences show up in the novel, and his inspiration for writing about these moments in history.

—Raluca Albu for Guernica

Guernica: You’re a reporter and a novelist. Some say those roles are on opposite ends of the creative spectrum. Are the two sides constantly at war with each other or is there symbiosis between them?

Jonathan Weisman: This novel was hatched on one of an endless line of dull, dutiful domestic trips that White House reporters take with the president. Sounds glamorous, I know, but in fact, you spend a lot of time waiting—while television reporters do their stand-up shots or Obama shakes hands or greets donors in private or just rests up out of sight of the cameras and reporters. I was covering the White House for the Wall Street Journal in 2009 and chatting with Helene Cooper of the New York Times and Anne Kornblut of the Washington Post about book projects when I said I couldn’t write a book I wouldn’t read—namely a journalistic current events book. But I had been ruminating over a novel off and on for twenty years. I laid out the rough plot lines, and Helene said, “Just write it.”

So I did.

Over those twenty years of rumination, I had worried that my honed journalistic sense, my understanding of the crux of a story, the need to represent both sides, and my penchant for speed and brevity would kill my fiction writing. And honestly, at first, it did. A chapter that should be twenty pages long, full of description, texture and build-up would end in five pages. The only question I seemed to be answering was, “and then what happened?” But with a lot of discipline— and some help and advice from my twin sister, Jamie Weisman, the real fiction writer in the family, I learned to slow the action down, write with more depth, and drown out the journalist in me. I needed him to go away. It wasn’t easy, but before long, the process of putting a story to bed, putting my children to bed, and picking up the mantle of the fiction writer became an escape—and a pleasurable one.

History—the non-fiction version—must inform the fiction to make it truthful; too much of it and your genres are colliding.

I did have thoughts—well, maybe fantasies—that my newfound skills of description, dialogue and voice would translate back into my journalism. But the professions of novelist and journalist are very separate. As a novelist, you are ultimately working for yourself. Yes, you need the approval of a publisher and an audience, but what is valued in fiction writing—style, individual voice, insight—is scorned by the editor who is combing through your newspaper article. You may, on occasion, be able to slip something through, but newspapers want information, not insight.

As for time to write, the long plane rides of the early Obama White House years were invaluable for gushing out the first draft of this novel. I was very disciplined when home—lights out for the girls at 9:00, two hours of writing for me. It was murder on my marriage.

Guernica: Your book so skillfully takes us from conservative Brighton, England to the middle of revolutionary Angola, while maintaining the emotional truth of the love and dysfunction in the Bromwell family. What advice do you have for writers who want to write across genres but struggle with reining in the larger socio-historical context?

Jonathan Weisman: I’ll answer that excellent question with a bit of a confession: I ain’t that great at it. The first draft of No. 4 Imperial Lane (then entitled Empires End) had long digressions into the history of Portuguese colonialism, not just in Angola and Guinea-Bissau, where the novel leads us, but Goa, Macau, even a tiny West African enclave called Ajuda, once a Portuguese redoubt in modern Benin. I had generals recount counterinsurgency strategies and plot coup attempts out loud. The journalist and history buff in me loved the stuff. Some day, maybe, there will be a director’s cut of the novel. But it bogged down the plot and took the focus away from the characters. I have a wonderful agent, Rayhane Sanders, who helped whittle it down, and an editor at Twelve Books, Libby Burton, who chiseled away further. I went so far as to count words and pages to make sure character development and plot were in rough balance, while history took a much smaller role.

There is, in my mind, no higher compliment to pay a non-fiction book than to say it reads like a novel.

So my advice, whatever its worth, is to continuously ask, how is this historical aside serving the characters of the novel, and if it is not, how necessary is it for the plot? Imagine the book without it completely. If that seems impossible, how about half of it? History—the non-fiction version—must inform the fiction to make it truthful; too much of it and your genres are colliding. It can also be a crutch, telling, not showing. Sure, I could recount at great length the final months and days of the Portuguese in Guinea, and I could infuse that history with great drama. It was dramatic. But in narrowing the lens to what my characters are seeing, a tiny piece of the action without the larger understanding, I keep the reader in their story, not the historian’s. You share their bewilderment. If I also showed you the broader historical facts, you wouldn’t share their suffering. You’d scorn it.

Guernica: What is fiction able to do that is harder to pull off in nonfiction?

Jonathan Weisman: There is, in my mind, no higher compliment to pay a non-fiction book than to say it reads like a novel. That says a lot about both. Lawrence Wright’s dense, exceptionally informative history of Al Qaeda, <target=”new”>The Looming Towers, gave me the sense that I had learned everything I could ever need to know about the run-up to 9/11, and I couldn’t put it down. Frank McCourt’s <target=”new”>Angela’s Ashes was so playful, sad, and moving that to this day I have a hard time believing it was non-fiction. My 15-year-old daughter had to read a memoir over this summer for school. She was thinking, Frederick Douglas or Helen Keller. I told her, Angela’s Ashes. The biologist E.O. Wilson was asked why he had written a novel, <target=”blank”>Anthill, after so many non-fiction works. His answer: “Non-fiction books are what you buy. Novels are what you read.”

It is simply much easier to infuse life, feeling, and higher truth into a novel than a non-fiction work, to find the license to write truth without being wedded to fact. After so many years as a journalist, I found it remarkably liberating to diverge from fact, while remaining mindful of the historical timeline. Much of David Heller’s adventures in 1980s Brighton in No. 4 Imperial Lane are autobiographical. I did go to the University of Sussex (although in 1985, not 1988); I did take a year off college to make a go of a relationship with a British girlfriend, and in that year, I did work as a scarcely paid volunteer for a quadriplegic fallen aristocrat and his alcoholic sister, who really did speak in Shakespearean verse because that had been all she was taught by the tutors on her parents’ estate. But in my fictional recounting of that time, I needed a way to give some back story to the quadriplegic’s pre-accident life without introducing a whole new story line on top of Elizabeth’s adventures in Africa and David’s in England. So I conjured letters that did not actually exist. They not only told of Han’s life in Paris but established the relationship between brother and sister before the family’s fall. I needed a stronger reason for David’s refusal to go home than wanderlust, so I created his dead sister. I needed a narrative arc in David’s Brighton year, something he was building toward. Why not a romance? Never happened, but all the better. This is fiction.

I found, in fact, that as I revised and layered, my own story became buried in a better plot and a higher meaning. Yes, sometimes truth is stranger than fiction, but usually fiction is just better.

Guernica: Your own young adult years are full of adventure and travel. No doubt that spirit of exploration infused this book.

Jonathan Weisman: One of the great sadnesses of my life, as I take stock at middle age, is the sense that the adventure largely ended by the time I was twenty-five. From nineteen to then, I studied for a year at the University of Sussex, took a year off to travel, to live with and care for a quadriplegic, to nurture my first long-term romantic relationship, to end that relationship, meet and marry, to serve in the Peace Corps in West Africa and the Philippines, and to travel a ridiculous amount on as little money as possible, through Europe (Western as well as the then-communist East), Africa, Asia, and Central America.

When I was in the Peace Corps, there were middle-aged men—often divorcees—hanging with the young volunteers, trying to relive their youth. I don’t hanker for that. I am not trying to be young again. But I do feel the need to capture that energy in story form before it slips from my mind, to recount those adventures if not relive them. As I said, I nurtured a novel based on my experiences in Brighton for twenty years. My second, as-yet-unfinished novel is set in the remote mountains of the Philippines, where I lived most of my Peace Corps service.

Because I had ruminated on what would become No. 4 Imperial Lane for so long, it came out in a rush when I finally turned the spigot. I had a draft done in a nine-month span, stretching between 2009 and 2010. Revisions were far harder. I have always had a hard time revising my work as a journalist, which was never much of a problem. You always have editors as backstops. Their job is to perfect your story. Most of them want to be useful. Novelists may be able to seek advice from readers and editors, but in the end, it is up to them to get the book right. In the three years it took to revise and re-revise my novel, there were certainly times I did lose interest or at least had more pressing things to do. Months would go by, and the thought of tackling a 300-page book again was agonizing.

But I wanted it done, and I had people who believed in it. I hope I will get to novelize my present circumstances at some point. I have some great stories to tell.

Guernica: Both of the settings in your novel deal with the end of an empire. How did you think through those politically charged elements of the story?

Jonathan Weisman: Earlier you asked whether my journalism career informed or impeded my fiction writing, and this question taps the one area of misgiving that I feel about mixing fiction writing and newspaper reporting. I have written for a conservative-leaning newspaper, the Wall Street Journal, and one that is certainly perceived to lean left, the New York Times. I have prided myself with striving for objectivity, something many literary-minded critics dismiss as impossible. But in Washington, reporters are practically the only people who actually spend time talking to Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals, and I find the longer I report in Washington, the mushier and less conclusive my own views are. I like it that way.

For all the worship that Ronald Reagan elicits in conservative circles in the United States, I would venture that Thatcher did far more to reshape British society than Reagan did here.

That is not my role as a fiction writer, and recounting the Thatcher years in Britain is by definition political, especially for an American audience. Liberals in the United States probably don’t have great passions about Margaret Thatcher, one way or the other. Conservatives do, and for good reason. For all the worship that Ronald Reagan elicits in conservative circles in the United States, I would venture that Thatcher did far more to reshape British society than Reagan did here. When I moved to Britain, the utilities were state-run. The telephone company was state-owned. So were the main radio and television stations, as was the main airline and railway. By the time I left, most of that was privatized. Thatcher had broken the miners’ union, all but crushed the Labour Party, dramatically cut back the welfare state, even flirted with a poll tax. In the circles I ran in, Reagan was mocked as a childish dolt. Thatcher was despised.

In dealing with such emotions, it was helpful to have the narrator be an American exchange student. David could not possibly share those passions. But I probably pulled some punches, mindful that I did not want the novel to be read as a leftwing screed by a practicing New York Times reporter. I was careful to mock the incendiary, leftwing politics of the day as I wrote of the pain that Thatcher’s policies had inflicted on the lower reaches of British society. It is not a major part of the novel, granted, but I could imagine being criticized by the same people who excoriate the “false equivalence” they read in the newspaper when they believe on some matters, we should be taking sides, not reflecting both equally. I’ll take that point.

The African sections were both less and more tricky, less because, for obvious reasons, I saw no reason to show sympathy for Portugal’s fascist colonialists, more because of the issue of race you asked about. Portugal’s rulers were the bad guys, full stop. Their vision of the Estado Novo—New State—with far-flung “provinces” from Angola to Macau insidiously infected my doctor, Joao Goncalves, who refused to take a side or a stand. As Greater Portugal collapsed, so did Joao. He brought his young wife, Elizabeth, down with him. If that is political, so be it.

Ultimately, this is a novel of white characters recounting an experience that has no race: hubris and its inevitable fall, whether on the intimate scale of the Bromwell family or the massive scale of empire.

Guernica: Writing about race, power, and identity is a layered and loaded practice. What did you have to consider while writing about colonial Africa as a white westerner?

Jonathan Weisman: I was very conscious of race as I was writing. I was lucky to have spent real time in Portuguese Africa, but I am white and my main characters are white, outsiders at sea in the “Dark Continent.” I tried to remedy that disconnect with two characters, Angélica, Elizabeth’s Portuguese teacher and erstwhile friend, and Jose Mendes de Farinha, nom de guerre Comrade Henda, a guerrilla fighter whose true story I stumbled on while researching the Portuguese wars in Africa. I made Angélica a Cape Verdean, swept back to Africa from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to give me a bridge between the West and Africa, a translator of sorts beyond English to Portuguese. Henda I tried to make sympathetic and understandable, a stand-in for Africa’s aspirations for independence. But I was sparing with both characters. I did not want to lean on them so heavily that I would sound condescending, nor do I pretend to speak for the black experience in Africa. That would be ridiculous. Ultimately, this is a novel of white characters recounting an experience that has no race: hubris and its inevitable fall, whether on the intimate scale of the Bromwell family or the massive scale of empire.