A from-the-ground report on how the tapping of Angola’s natural resources has kept the country a killing field, and made it one of the world’s most glaringly inefficient kleptocracies.

Photograph by Paolo Woods

Photograph by Paolo Woods

Jim is an American oilman from Oklahoma, and he’s sitting in a darkened corner of a whorehouse in downtown Luanda. He’s fat, white, gaping lazily at the black African prostitutes in fuchsia-colored miniskirts and heels who patrol the floor. He orders a beer, sits back on the leathery couch to watch the dimmed lights flicker off the shiny bar tops, the dark wood of the balustrades, the crystalline shimmer emanating from the disco ball that dangles like a low-hanging fruit. Waitresses in short, tight tops, jeans, and fuzzy rabbit slippers pad around sleepily taking orders and comments. Jim has been to this place and places just like it so often in the twenty years he has lived and worked in Africa that he seems — and I wonder if he also feels this — to fit in as comfortably here as anywhere else I might imagine for him, a bar in West Texas, a beetle-stained butte, gazing contentedly at the sand.

More men have begun to drift in now, and along with them more languages. There is a smattering of French. And German. There’s Dutch, Spanish, and of course Portuguese, the language of the colonizers. The diamond men are coming, Jim says. And the arms men, too. The barman pumps the volume up, Bobby Brown then Shakira. More women stream in.

African oil is changing, Jim explains. For a long time, several decades in fact, Nigeria was the undisputed king of the continent. It had the best oil and more of it than anyone else. Jim worked there for years, risked kidnappings, armed attacks on heavily guarded offshore rigs, the mighty chaos of Lagos. Like other oilmen he lived in a compound with grocery stores, restaurants and bars, and rarely ventured outside, and then only when it was absolutely necessary. But in 2007, times are changing, he says, ordering another bottle of Nova Cuca, a local beer, from a passing waitress and taking a slinking, unsmiling look at her bottom as she walks away. Angola is becoming the new king. Angola has everything an expat could want. There’s only one thing: the Chinese are taking over here, where there is more oil than anywhere else in Africa.

Oilmen like Jim are a little bit nervous about this.

The Chinese don’t say much though, he says, not much at all.

The Portuguese built Luanda slowly, over five centuries, in one of Africa’s longest colonial episodes; in the process they secured coastal dominance and, with their presence in Mozambique, an entryway to both sides of Africa’s slim bottom. But in 1975, after nine years staving off independence, the Portuguese packed up and left, some of them so abruptly, in fact, that many of the oldest ruling families abandoned furniture, cherished heirlooms and entire crates of personal treasures — centuries of heritage — on the cratered runways of Luanda’s airport as they scrambled desperately to secure the last seats in the last planes back to the last place they had been — Europe. For the next quarter century, Angola, home to 18 million people, was transformed into a Cold War battleground as the country descended into civil war. It pitted the forces of UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), led by Angolan rebel Jonas Savimbi and supported by the United States, Israel and the apartheid regime of South Africa, against those of Agostinho Neto, Angola’s first post-independence president, and Jose Eduardo Dos Santos, a former foreign minister whose MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) received arms and funding from the Soviet Union and Cuba. By the time Savimbi was finally killed in February 2002, shot fifteen times during a battle on the outskirts of Huambo, the war was into its twenty-seventh year and more than half a million Angolans had already died. Dos Santos took power immediately and remains president today.

A quarter million people were left mutilated and handicapped by the war. And tens of thousands were without homes or families or the means to secure a living, and they began to settle on the fringes of the capital in ghettos devoid of water, electricity, or sanitation. But in many ways, they were the lucky ones. Much of the rest of the country was shocked into isolation, lost in valleys or vast tracts of ruined wilderness whose connection to the rest of the country had been blown apart by the war. Roads were destroyed or gutted and pitted beyond repair. Hundreds of thousands of Russian and Chinese anti-tank and PMN-2 anti-personnel mines littered the countryside, making Angola one of the most mined countries on earth. The mighty railways the Portuguese built in the first quarter of the twentieth century that crisscrossed the country, stretching eastwards toward Congo and the rest of the continent were destroyed a decade into the war and have been rotting ever since. Even as cities like Luanda succumbed to water, waste, and despair, the denizens of the battered countryside continued to arrive in droves, often only to die soon afterward, starved, beaten and run-down, mirrors of the country that birthed them.

Now the war has ended, three hundred and fifty miles south of Luanda, on the outskirts of the old port town of Lobito, a dozen or so Chinese laborers sit at wooden tables and smoke. Along one wall are several wooden cots where more men sleep under delicate blooms of mosquito netting. A steel bucket filled with fish lies on the floor, and a couple of mangy dogs prowl nervously nearby. Huge piles of steel rebar lie scattered alongside cutting machines. Outside, two Angolan guards armed with handcuffs look only mildly alert.

The black gold will run out sometime, Jim says, but not for a long, long time. There’s so much goddamn oil here, no one knows what the hell to do with it all.

“We don’t feel unsafe here,” says Charlie, the 23-year-old Chinese interpreter and right-hand man for the warehouse boss, Mr. Li, an engineer from Guilin in Guangxi Province and the local director of the Guangxi Construction Investment and Development Group (now known as the Guangxi Investment Group). Mr. Li wears an ’80s style Polo T-shirt, worn blue jeans and tattered black loafers. He had never left China before he landed in Africa six months earlier and now, sitting in this dingy warehouse with dust and rebar scattered across the floor, and a crop of ignorant, peasant workers who’ve been sent here under his command to rebuild a country he had never even heard of a year ago, he fingers the worn pages of a book he is reading called The Mysteries of History.

“This book says that Egyptians could not have built the pyramids alone,” he says through Charlie, who is wearing a T-shirt with the words “E for Emotion.”

“It says they were helped by aliens. They were lacking the technology to do these pyramids.”

Mr. Li is the only one of his thirty-man team with any semblance of privacy, a small room that doubles as an office with a computer, a calculator and several boxes bearing the logo for the Chinese International Fund, a murky state-controlled enterprise that no one, especially not the Angolan government, has so far been willing to discuss with me. Mr. Li appears no more inclined than any others to do so, either. The pinky nail on his right hand is very long and with it he thumbs his small mustache and goatee as he considers again the book of mysteries in his lap.

“We can overcome difficulties,” he says, finally. “The Chinese are very good at working in difficult places.”

Charlie agrees with this. He wants to stay in Africa for at least ten years. He’s learning Portuguese.

“Don’t you think that I can adapt to another culture and another language?” he asks me, and without waiting for an answer, confirms. “The Chinese are very strong.”

And the aliens? I ask Mr. Li.

“I think it’s true,” he says, and nods, and blows a long sigh of smoke into the dust-choked room.

“Yes,” Charlie echoes. “True.”

Back in Luanda, the men almost outnumber the prostitutes now. And everyone, including Jim, is having a good time. This is how it is, and how it should be. The oilman smiles at this new frontier. There are still large tracts of Angola that are completely unreachable by road because the landmines have yet to be removed. Seems the only way in and out is by helicopter. Those diamond and arms men are always skulking around up there. By and large, Jim stays down here, in the flatlands, by the shores, the easy life, on the rigs now and again, but always back here. The black gold will run out sometime, he says, but not for a long, long time. There’s so much goddamn oil here, no one knows what the hell to do with it all.

The expatriate life appeals to him. He has had it with American women. Some of the prostitutes come from Congo, across the river. Many come from right here in Angola. He tells me it’s common for men like him to take on wives and girlfriends in a casual way, here and there, when it suits both of them. The man will pay for items, small and large. He has rented apartments and cars for his girlfriends. He keeps a gun in case the real boyfriends and husbands come calling. It doesn’t bother him much. It’s a fair transaction and most of the time everyone agrees to be on the same page. You have to watch out for HIV, he says. He has lost count of the times he’s contracted malaria. He took pills for a while to stave it off, but gave that up years ago, back when the only medication on the market induced psychosis and nightmares and made your piss go green, he says, and half goddamn blind, and hell with it, he’ll just take it when it comes because, well, that’s what he’s decided. You can tell the diamond men, he says, they always seem to be the ones wearing glasses. How long will the boom times last? Until every one has anted up and drunk long and hard and had a good long suck at the burgeoning teat, the oilman says. And the Chinese?

“They’ll learn,” he says, “They’ll learn.”

Less than a year after the ceasefire, in 2003, Angola signed a deal with the newest colonial arrival to Africa, China, to rebuild what Angola had shattered. In 2004 China extended $2 billion in open credit to Angola for a series of infrastructure and development projects. By 2007, the credit lines had quintupled, to $10 billion, and Angola was fast becoming China’s biggest advocate, touting its superiority over the standard Western donors like the World Bank and the IMF, whose bureaucratic restrictions had angered the government and, in their view, only hobbled Angola further. Angola opted for the simpler and quicker Chinese solution. By 2007, only Sudan, under the autocratic rule of Omar El Bashir, was receiving more money and technical assistance from Beijing. By 2010 Chinese credit lines to Angola had doubled yet again, to more than $25 billion, fully one quarter of China’s $100 billion investment in more than twenty countries across Africa. In return for these generous credit lines and the promise to help Angola develop, the Chinese secured rights to payment in oil and natural gas for its own economy, and access to Angola’s developing markets that fit nicely with its global ambitions. The Chinese themselves have been streaming into Africa by the hundreds of thousands over the last decade, and nowhere more so than in Angola. In 2007, when I visited, there were no official figures on how many Chinese were working in Angola, but by 2010, the Angolan government was acknowledging at least 70,000 Chinese in the country. Unofficial estimates place the figure much higher.

“The Chinese are ready to die here in Africa,” he says. “They’re happy to die, they’re not afraid of mines because they know their families will be well compensated.”

Sitting across from me to explain all this during my last visit, over a bowl of noodles and Chinese beer, is a Chinese official in his fifties, wearing a thin, gray shirt unbuttoned one button too far. A cigarette is accumulating ash between his fingers. We’ve been talking about the recent news that a Chinese laborer died in a mine explosion. But it isn’t remnants of war that’s killing the Chinese in Angola. It’s possibility. “The Chinese are ready to die here in Africa,” he says. “They’re happy to die, they’re not afraid of mines because they know their families will be well compensated.” They come from all over China, he says, the poor countryside where even menial jobs are scarce and opportunities for advancement virtually nonexistent. The leaders of China, he says, are similar to these peasant workers. “They’re all from rural areas, they’re mostly poor, and money is important to them, they know how to save money, and they also know power because in the rural areas the only ones with power are the ones with money, and the ones with money know how to get the power.” They are illiterate, hungry, desperate to feed their families, people like the miner we’ve been discussing whose bulldozer rammed into an anti-tank mine and tore him apart — these are the Chinese who have helped midwife Angola’s post-war rebirth. The dead miner’s body will most likely be cremated, the ashes collected and returned to the family back in China. A wife or relative may come to Angola to pick up the remains, but she has the right to refuse to do so as well. In addition, the family will be financially compensated, with perhaps as much as 300,000 yuan, or roughly $40,000 — a small fortune for a peasant in rural China.

Meanwhile, what was once one of Africa’s most failed states now has the region’s highest annual per capita GDP growth rate — 27 percent, eight times the continental average.

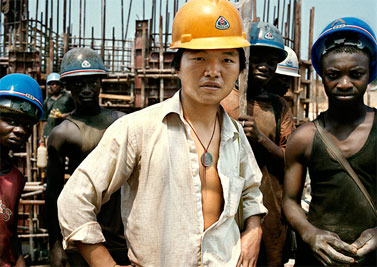

Across Africa, and especially in Angola, China has insisted on importing its own cheap labor from home. Traveling on the road south from Luanda to Lobito, two friends — a writer and photographer — and I stopped to watch a few dozen ragged Chinese workers struggling in the noonday sun, breaking rock on the side of the road to help rebuild the coastal highway. The work looked painstakingly monotonous, hour upon hour of hammering, picking and organizing quartzite and bedrock into roadside tile work. Now and then an officious manager wearing wraparound dark glasses and carrying the latest Nokia strolled by to check on progress, but by and large the work was silent.

In other cases, the toughest manual labor was delegated to the Angolans with Chinese oversight. The Angolans complained that the Chinese spat too much and paid them too little or not at all and dismissed them as little more than monkeys, imitating the “oooh, oooh, oooh” sounds of a chimpanzee. The Chinese know only two words in Portuguese, one Angolan told us.

“Cava, cava,” he said, with a bitter smile. “Dig, dig.”

“Rapido, rapido,” said another. “Faster, faster.”

The Chinese, in turn, wanted little to do with the ordinary people whose country they had come to salvage from the wreckage of the last forty years. One day I met Xia Yi Hua, a middle-aged CEO from Beijing who had been in Angola for the last year and a half. He had contracts with the government to build a hotel in Baya Falte for some of Dos Santos’ most loyal military generals and a police academy in Baya Azul. He welcomed me into a spare waiting room and sat down comfortably in a stiff-backed chair. He got his chicken locally, he told me, but received regular shipments of packaged goods from China. His company sent him food. Everything in his office building, a set of low-rise prefab construction at the end of a highway leading out of Lobito, was either assembled in China, or made by Chinese laborers in Luanda. The wooden coffee table at which we were sitting was made of a rare and beautiful dark-colored Angolan wood, but Xia Yi Hua had brought a Chinese carpenter in to assemble the table. He had his own set of rules. No one from his construction company, China Jiang Su, was allowed to have romantic or sexual ties with Angolans.

“The chief for Jiang Su says that the Chinese who have wives in China, they don’t have the right to be with Angolan girls.”

Anyone caught frequenting local girls, he said, gets sent home. “Yes, fired.”

The gap between the two cultures was too vast, he explained, unbridgeable even in matters of the heart.

“For an Angolan to marry a Chinese girl is very bad too.”

What he wants most, it seems, is more Chinese workers.

“We can’t expand fast enough,” he laughed. “I need more Chinese.”

The Chinese reluctance to hire more local workers, perhaps more than any other single factor, has continued to irk the Angolans and has led to tensions between the two countries, and as the number of Chinese workers in Angola has continued to swell, local resentment against them has also grown. Over the last two years, human rights researchers have been documenting an increase in kidnappings and beatings of Chinese workers, and a “steady pattern of discrimination” has started to emerge, says the Center for Human Rights Coordination in Luanda, according to the Wall Street Journal. In 2009, the Chinese embassy issued an online warning about threats to Chinese citizens in Angola, citing two cases in which armed robbers stripped Chinese businessmen of thousands of dollars in cash and equipment. Further north, in the oil-rich Cabinda Province, Chinese workers have suffered a spate of attacks including beatings, kidnappings and threats by a newly formed separatist group called the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda. Much of this violence has its roots in the attitude the Chinese originally adopted when they first arrived in Angola and other parts of Africa — namely, that Africans were ill-equipped or simply unable to perform complex jobs. Some Chinese contractors sheltered their imported Chinese laborers away in neat little roadside camps surrounded by barbed wire, armed guards and dogs. Even if you managed to get inside — which we once did by pretending to be cement merchants from South Africa touring the country to drum up business — it was impossible to talk to any of these sequestered workers, which raised the question of whether the Angolans had it as bad as the Chinese did. The sporadic and sometimes confusing nature of the meeting of these two cultures produced much rancor and very little mutual understanding.

The same Angolans who helped turn this corner of Africa into a killing field have more recently helped make it into one of the world’s most glaringly inefficient kleptocracies.

“They think we’re just a bunch of savages,” said Fundulu, my Angolan translator.

He smiled.

“We don’t think too much of them either though.”

The United States has been drilling for oil off West African coasts for several decades. It was a tricky business for several reasons — corruption, war and widespread poverty made the massive extraction of valuable natural resources by American oil companies particularly unsavory — but there were always people willing to do it. People like Jim, who wants to dance now. He swaggers into the crowd near the bar where the lights are pulsating wildly and stands amid the gyrations, an unconcerned white totem in a brawl of desire. Beer in hand, bald, he is starting to look the part of the lost foreigner. Angola is a sinkhole of money, he says, and one needn’t look far to see it. He rents a house in Luanda for $26,000 a month, and that’s a steal. Some of them are going for $40,000 or more. Renting a car will set you back around $14,000 a month. Luanda, he says, is the most expensive capital city in the world. And all that oil money is caking the city with greed. The same Angolans who helped turn this corner of Africa into a killing field have more recently helped make it into one of the world’s most glaringly inefficient kleptocracies. Although the scale of the waste extends to virtually every corner of industry, it has been most visible in the oil sector. American oil tankers looking to unload a shipment of a few million gallons of crude recently sucked up from the ocean floor, are obliged to pay exorbitant fees — sometimes as much as $80,000 a day — for every day they wait outside a harbor. They don’t care, says Jim, they’re making so much money out there that $80K is peanuts to them. ’Course, that might be changing now, he adds. The Angolans are good at corruption, but the Chinese are making them even better. All those untold billions in credit extensions have disappeared into the pockets of the richest officials. You rarely see them, but you see their cars — bright yellow Hummers slinking along muddy roads with American rap music blaring. Jim echoes a commonly expressed sentiment about Chinese ambitions in Africa – they’re hungry for African resources and they’ll do anything to get them, including and especially greasing the wheels of corruption in poor and messily governed countries like Angola.

“They’re in it for themselves,” Jim says, but then adds: “ ’Course, isn’t everyone?”

Now these American and British companies have started to train the Chinese to do offshore drilling, and that’s another reason they’’e here, to learn the sophisticated offshore technology that’s been keeping them out of the game for so long. They had a rougher time of it in Nigeria, he says, though they tried there. He raises his whiskey in a toast. An attractive young woman sidles over to us and puts her arm around Jim and he smiles and returns the favor and the three of us drink up, and she lingers a while, but not too long, and when she realizes there isn’t any business here she politely moves along. Jim points to a tall, thin man with glasses and a neat, pressed look.

Diamonds, Jim says.

The near totality of Angola’s partnership with China was, at least when I was there, managed by the China International Fund, whose stickers and logos are a ubiquitous presence in Luanda. Oil and gas receipts are exchanged for rebuilding, and most transactions are conducted through high-level exchanges between CIF officials and the Angolan officials who oversee the projects. In addition, CIF has secured a foothold in the growing economy into which it has been slowly pushing private and semi-private companies with close ties to the state-controlled behemoths like Exim Bank that regulate China’s expansion across Africa.

There are few organizations as impenetrable as the China International Fund. Soon after it was first established, CIF contracted with the Angolan government for at least thirty massive infrastructure projects across the country, including 240,000 apartments in Cabinda, an international airport, a skyscraper that would become one of the tallest buildings in Luanda, and the Benguela–Luau railroad. After I left in 2007, virtually all of those projects were halted because the government had failed to make the necessary payments. (In the years since, similar projects have fallen by the wayside, and frictions between the Angolan government and the Chinese have continued to mount.) Yet CIF officials were managing to get unencumbered access to the highest levels of the Angolan government. According to one Chinese official, who asked to remain anonymous, even Chinese embassy officials didn’t know how to get in touch with the elusive CIF.

“It’s very complicated, very messy,” said the official. One day in Luanda, I asked a Western diplomat what he made of CIF’s relationship with the government and where all the money was going. It was so convoluted and corrupt, he said, that most observers had simply stopped trying to understand where all the money had disappeared. The monetary figures were so high, and the relationships so murky and complex, that the government itself had in all likelihood lost count, and in any event it was unlikely it cared that much to begin with. “Are the numbers 100 percent legitimate? Are they real? We don’t know,” the official told me. “They cannot absorb all the money coming in, nor do they have the capacity to rationally spend it.”

One day in Lobito I woke before dawn and made my way down to a grassy expanse on the edge of town where the trees had been cleared and a rusty set of train tracks stretched off toward the east. It was chilly outside, and the sea air off the Atlantic brought with it a tang of salt and gulls, and the smoke from campfires that were beginning to rise with the morning. In the clearing stood a train that looked so broken and decrepit it came as a surprise when people began clambering aboard. During much of the war this railway line continued to run its regular route between Lobito and the vast stretch of the interior, including the town of Huambo, where Joseph Savimbi had his base and from where he ran a bustling diamond-smuggling business to fuel his war coffers. For many years this train was the only thing connecting the inhabitants of Savimbi’s inland empire to the rest of the world. In 1992, the war affected forty-seven bridges on the line, soldiers added land mines on both sides, and as a result the interior was cut off from the rest of the country.

The train filled quickly. Brightly dressed women with large sacks of food and clothing settled down on the hard plastic seats, the chill air wafting through open windows, chatting with the vendors outside who jostled for their attentions. A jovial conductor wearing a 1970s-era cap, a jacket with gold epaulets, and knockoff Ray-Ban sunglasses meandered down the aisle taking tickets. Moises was his name, and he told us that in the months to come, if the Chinese fulfilled their promises, he’d have a whole new train to drive and new tracks to drive it on, and the years of lateness and isolation would be over.

As my three traveling companions – two European journalists and our translator – and I got comfortable, the merchants came to us. They carried huge sacks of rice on their heads, bags of beans and corn and bottles of water, chickens tied by their feet and slung over wooden poles, bowls of something steaming for now, and bags of peanuts for later, and all of it pushed and shoved and thrown up at us amid a cacophony of shouting and grinning and piling on, and did this three times each week. The Angolans rebuilt the 96-mile stretch of track from Lobito eastward to Cubal in 2005, but the remainder of the line, which extended another 706 miles to Luau on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo was still in shambles, and there were rumors that Chinese teams had been deployed inland to begin rebuilding the rest of what was once one of Africa’s most famous train tracks. This was to be the signal project of China’s work in Angola, and the Chinese company, CRRCC, that was said to be hard at work on this railroad, was the same that had laid several thousand miles of track across the breadth of Tibet, fifteen thousand feet high in the Himalayan wilderness. We had decided to go in search of them in Angola’s wilds. We’d take the train as far as it would go, to Cubal, then hire a car and keep going until we found the Chinese.

Soon the first lurch came and then another, and slowly the train picked up speed as the last of the hawkers jettisoned their heaviest goods and ran alongside us thrusting what remained of their salable items toward us and then slowly dropping away out of sight as the old warhorse gained speed and took off.

Three hours later we arrived in Cubal.

Our hired driver headed us in the direction of Chimbassi, a town about nine miles to the east of Cubal where, he informed us, the Chinese were hard at work on the next section of track. “They’re everywhere there,” he said. “Where there is one there are always more.”

But, when we arrived, there were none.

“What!” said the driver, stunned. “They were here just last week.”

Instead, a vast tract of what looked like excavated ground stretched out emptily in front of us. There were signs the Chinese had been there recently — a set of old railroad tracks had been uprooted and what looked to be fresh foundation for new tracks had been laid down. A few signs of human habitation remained: stray packs of sugar, some anti-malarial medication, a small garden where some parsley poked meekly from the red African dirt.

Our driver suggested they may have moved on — to Ganda, another small town about twenty-five miles further east toward the DRC.

The Chinese had been there, we were told by a crowd in Ganda who had gathered around our car, but they left two weeks ago to return to their base at Alto-Catumbela, a two-hour drive east. We had hoped to find the Chinese hard at work extending, after three decades of war, the famed Benguela–Luau railway line that would once again reconnect Angola with the rest of the world, or at least the rest of Africa. But ubiquitous as they had been elsewhere, here they seemed to have gone into hiding, lost in the great wilderness of post-war Angola.

“It’s a hundred percent per year,” he said. “That’s unique to this country. You don’t see that anywhere else in Africa. Why? Because the Angolans are pushing like mad to have everything done by tomorrow. They want the best and the fastest. If they want a hotel, they don’t want a three-star, they want a five-star.”

In the far distance, massive mountains of stone shaped like perfectly rounded cones rose up on the horizon. Vast forests of palms stretched between them, and from these rose the occasional baobab tree, ancient and glowing in the afternoon sun. This land was so heavily mined during the war that de-mining organizations had placed red stones painted with skulls and crossbones on the side of the road at various intervals, wherever a mine was suspected. The closer we got to Alto-Catumbela, the more frequently we began to see the red stones and the worse the roads became. The driver told us not to worry because he knew where the mines were. Beside the road, children scampered here and there, hopping over stones and crisscrossing the ground as lightly as deer. By 2008, one de-mining organization found over 1,600 mines in this small town alone.

Rain was threatening as we wound our way to the end of the road where a defunct paper mill sat in broken abandonment, its windows shattered, doors cracked open, and a slash of brick and mortar debris crumbling out of every shelled hole. Surrounding it was a wall where the words “Long Live Proletarian Internationalism” in red and blue paint were fading and cracking. A few men stood idly by smoking cigarettes and watching us casually. Surrounding us was a field of bright green cassava and corn, and sinking fast into the ground on its edges were at least a dozen tractors, earthmovers and bulldozers. It looked like a bombed-out refugee hideaway for families that may have sought shelter during the war. We wondered if the Chinese had lived here and soon asked one of the men.

He shook his head.

No, he told us, the Chinese had packed up and left a week or two earlier — but not, he added, before they ate their dogs. He threw his cigarette to the ground as he and his companions broke into peals of laughter.

Zulu is the one bar in Lobito where everyone goes — the Chinese, the American oil workers, the journalists — and it sits on a wide strip of sand that looks out over the bay and the calm gray waters of the Atlantic. There’s a thatched roof hut with a bar serving tropical drinks, and several wooden tables outside. One afternoon I met Zhou Zhenhong at Zulu. He had been in Africa for five years; two in South Africa, which he found too dangerous, and two in Zambia, which he found too slow and too poor. Angola, on the other hand, was safe enough and rich enough to make it worth his time. When I met him, he hadn’t seen his family in two years and didn’t know when next he would. He used to work for CIF, but in 2006 they pushed him out and told him to start his own company. He started with $1 million in loans and since then has made several million more. “It’s a hundred percent per year,” he said. “That’s unique to this country. You don’t see that anywhere else in Africa. Why? Because the Angolans are pushing like mad to have everything done by tomorrow. They want the best and the fastest. If they want a hotel, they don’t want a three-star, they want a five-star.”

Zhou’s teeth are rotting and brown. He smokes one cigarette after another. Of all the Chinese I met, he seems to me to be the one who has figured out the system. He’s close enough to the state-controlled companies in Beijing to get the support he needs, but far enough away for nothing else much to matter. Now, taking in the remainder of the day at Zulu, he appears to have shed the dependence of the bureaucrat he once was, and adopted the buccaneer attitude of the Chinese capitalist — or, perhaps, African colonialist — he has become.

“We want more staff and more equipment, and every year is busy,” he told me. “We don’t even have time to build our own houses or make improvements for our life because we’re so busy with the projects.”

“We camp, we live wherever, whatever,” he said and snubbed his cigarette out in the ashtray for a very long time. The ocean nearby looked more like a lake, peaceful and flat forever, a gray sheen that spat little wavelets upon the shore and sucked them back out again just as fast.

By the time Jim and I left the whorehouse it was well into early morning. Dawn would come soon. The floor was thumping loudly. Everyone was talking to everyone else. The prostitutes had dispensed with all pretense of coyness and had instead become aggressive.

“What you want? ” they’d say. “Let’s go. Now.”

Jim watched them for a long while. More men were coming in, diamond men, arms men, oil men, all of them European or African. If the Chinese were anywhere, Jim told me, they were in the casinos, on the other side of town. I knew this to be true because I had seen them there myself, but I didn’t say anything. They’d be there all night.

“I’m drunk,” Jim said. I patted him on the shoulder.

And then we walked out into the dark night.

**Scott Johnson** is currently the Violence Reporting Fellow for the Oakland Tribune, an investigative reporting position funded by the California Endowment. He worked for the past twelve years as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek, and was chief of the magazine’s Africa bureau from 2007 until its close at the end of 2009. He spent most of the preceding decade reporting from the Middle East, covering wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Mexico, and covering politics and the economy in Latin America.